- Updated and expanded March 25, 2009 – Miltonic Sonnet, Nonce Sonnet, Links to Various Sonnet Sequences and additional Sonnets.

- After you’ve read up on Sonnets, take a look at some of my poetry. I’m not half-bad. One of the reasons I write these posts is so that a few readers, interested in meter and rhyme, might want to try out poetry. Check out Spider, Spider or, if you want modern Iambic Pentameter, try My Bridge is like a Rainbow or Come Out! Take a copy to class if you need an example of Modern Iambic Pentameter. Pass it around if you have friends or relatives interested in this kind of poetry.

- April 23 2009: One Last Request! I love comments. If you’re a student, just leave a comment with the name of your high school or college. It’s interesting to me to see where readers are coming from and why they are reading these posts. :-)

The Shakespearean Sonnet: Shakespeare’s Sonnet 129

The word Sonnet originally meant Little Song.

Sonnets are one of my favorite verse forms after blank verse. And of all the sonnet forms, Shakespearean is my favorite – also known as the English Sonnet because this particular form of the sonnet was developed in England. The Shakespearean Sonnet is easily the most intellectual & dramatic of poetic forms and, when written well, is a showpiece not only of poetic prowess but intellectual prowess. The Shakespearean Sonnet weeds the men from the boys, the women from the girls. It’s the fugue, the half-pipe of poetic forms. Many, many poets have written Shakespearean Sonnets, but few poets (in my opinion) have ever fully fused their voice with the intellectual and poetic demands of the form. It ‘s not just a matter of getting the rhymes right, or the turn (the volta) after the second quatrain, or the meter, but of unifying the imagery, meter, rhyme and figurative language of the poem into an organic whole.

I am tempted to examine sonnets by poets other than Shakespeare or Spenser, the first masters of their respective forms, but I think it’s best (in this post at least) to take a look at how they did it, since they set the standard. The history of the Shakespearean Sonnet is less interesting to me than the form itself, but I’ll describe it briefly. Shakespeare didn’t publish his sonnets piecemeal over a period of time. They appeared all at once in 1609 published by Thomas Thorpe – a contemporary publisher of Shakespeare’s who had a reputation as “a publishing understrapper of piratical habits”.

Thank god for unethical publishers. If not for Thomas Thorpe, the sonnets would certainly be lost to the world.

How did Thorpe get his hands on the sonnets? Apparently they were circulating in manuscript among acquaintances of Shakespeare, his friends and connoisseurs of his poetry. Whether there was more than one copy in circulation is unknowable. However, Shakespeare was well-known in London by this time, had already had considerable success on the stage, and was well-liked as a poet. Apparently, there was enough excitement and interest in his sonnets that Thorpe saw an opportunity to make some money. (Pirates steal treasure, after all, not dross.)

The implication is that the sonnets were printed without Shakespeare’s knowledge or permission, but no historian really knows. Nearly all scholars put 15 years between their publication and their composition. No one knows to whom the sonnets were dedicated (we only have the initials W.H.) and if it’s ever irrefutably discovered- reams of Shakespeare scholars will have to file for unemployment.

(Note: While I once entertained the notion that the Earl of Oxford wrote Shakespeare’s plays – no longer. At this point, having spent half my life studying Shakespeare, I find the whole idea utterly ludicrous. And I find debating the subject utterly ludicrous. But if readers want to believe Shakespeare was written by Oxford, or Queen Elizabeth, or Francis Bacon, etc., I couldn’t care less.)

Now, onto one of my favorite Shakespearean Sonnets – Sonnet 129.

The expense of spirit in a waste of shame

The expense of spirit in a waste of shame

Is lust in action; and till action, lust

Is perjured, murderous, bloody, full of blame,

Savage, extreme, rude, cruel, not to trust,

Enjoy’d no sooner but despised straight,

Past reason hunted, and no sooner had

Past reason hated, as a swallow’d bait

On purpose laid to make the taker mad;

Mad in pursuit and in possession so;

Had, having, and in quest to have, extreme;

A bliss in proof, and proved, a very woe;

Before, a joy proposed; behind, a dream.

··All this the world well knows; yet none knows well

··To shun the heaven that leads men to this hell.

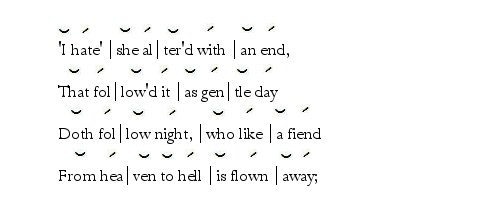

While this sonnet isn’t as poetic, figurative or “lovely” as Shakespeare’s most famous sonnets, it is written in a minor key, like Mozart’s 20th Piano Concerto, and beautifully displays the rigor and power of the Shakespearean Sonnet. Let’s have another look, this time fully annotated.

The Shakespearean Sonnet: Structure

First to the structure. Many Shakespearean Sonnets can be broken down, first, into two thematic parts (brackets on the left). The first part is comprised of two quatrains, 8 lines, called the octave, after which there is sometimes a change of mood or thematic direction. This turn (or volta) is followed by the sestet, six lines comprised of the quatrain and couplet. However, this sonnet – Sonnet 129 – does not have that thematic turn. There are plenty of sonnets by Shakespeare which do not.

In my experience, many instructors and poets put too much emphasis on the volta as a “necessary” feature of Shakespearean sonnet form (and the Sonnet in general). It’s not . In fact, Shakespeare (along contemporaries like Sidney) conceived of the form in a way that frequently worked against the Petrarchan turn with it’s contemplative aesthetic. The Elizabethan poets were after a different effect – as Britannica puts it: an argumentative terseness with an epigrammatic sting.

My personal analogy in describing the Shakespearean Sonnet is that of the blacksmith who picks an ingot from the coals of his imagination. He puts it to the anvil, chooses his mallet and strikes and heats and strikes with every line. He works his idea, shapes and heats it until the iron is white hot. Then, when the working out is ready, he gives it one last blow – the final couplet. The couplet nearly always rings with finality, a truth or certainty – the completion of argument, an assertion, a refutation.

Every aspect of the form lends itself to this sort of argument and conclusion. The interlocking rhymes that propel the reader from one quatrain to the next only serve to reinforce the final couplet (where the rhymes finally meet line to line). It’s from the fusion of this structure with thematic development that the form becomes the most intellectually powerful of poetic forms.

I have read quasi-Shakespearean Sonnets by modern poets who use slant rhymes, or no rhymes at all, but to my ear they miss the point. Modern poets, used to writing free verse, find it easier to dispense with strict rhymes but again, and perhaps only to me, it dilutes the very thing that gives the form its expressiveness and power. They’re like the fugues that Reicha wrote – who dispensed with the normally strict tonic/dominant key relationships. That made writing fugues much easier, but they lost much of their edge and pithiness.

And this brings me to another thought.

Rhyme, when well done, produces an effect that free verse simply does not match and cannot reproduce. Rhyme, in the hands of a master, isn’t just about being pretty, formal or graceful. It subliminally directs the reader’s ear and mind, reinforcing thought and thematic material. The whole of the Shakespearean rhyme scheme is hewed to his habit of thought and composition. The one informs the other. In my own poetry, my blank verse poem Come Out! for example, I’ve tried to exploit rhyme’s capacity to reinforce theme and sound. The free verse poet who abjures rhyme of any sort is missing out.

The Shakespearean Sonnet: Meter

As of writing this (Jan 10, 2009), Wikipedia states: “A Shakespearean sonnet consists of 14 lines, each line contains ten syllables, and each line is written in iambic pentameter in which a pattern of a non-emphasized syllable followed by an emphasized syllable is repeated five times.”

And Wikipedia is wrong.

Check out my post on Shakespeare’s Sonnet 145. This is a sonnet, by Shakespeare, that contains 8 syllables per line, not ten. It is the only one (that we know of) but is nonetheless a Shakespearean Sonnet. The most important attribute of the Shakespearean Sonnet is it’s rhyme scheme, not its meter. Why? Because the essence of the Shakespearean Sonnet is in its sense of drama. (Shakespeare was nothing if not a dramatist.) The rhyme scheme, because of the way it directs the ear, reinforces the dramatic feel of the sonnet. This is what makes a sonnet Shakespearean. Before Shakespeare, there was Sidney, whose sonnets include many written in hexameters.

That said, the meter of Sonnet 129 is Iambic Pentameter. I have closely analyzed the meter in Shakespeare’s Sonnet 116, so I won’t go too far in depth with this one, except to point out some interesting twists.

As a practical matter, the first foot of the first line |The expense |should probably, in the reading, be elided to sound like |Th’expense|. This preserves the Iambic rhythm of the sonnet from the outset. Unless there is absolutely no way around it, an anapest in the first foot of the first line of a sonnet (in Shakespeare’s day) would be unheard of.

Lines 3 and 4, of the first quatrain, are hard driving, angry Iambs. Murderous in line 3 should be elided, in the reading, to sound like murd‘rous, but the word cruel, in line 4, produces an interesting effect. I have heard it pronounced as a two syllable word and, more commonly, as a monosyllabic word. Shakespeare could have chosen a clearly disyllabic word, but he didn’t. He chooses a word that, in name, fulfills the iambic patter, but in effect, disrupts it and works against it. Practically, the line is read as follows:

The trochaic foot produced by the word savage is, in and of itself, savage – savagely disrupting the iambic patter. Knowing that cruel works in a sort of metrical no man’s land, Shakespeare encourages the line to be read percussively. The third metrical foot is read as monosyllabic – angrily emphasizing the word cruel. The whole of it is a metrical tour de force that sets the dramatic, angry, sonnet on its way.

There are many rhetorical techniques Shakespeare uses as he builds the argument of his sonnet, many of them figures of repetition, such as Epanalepsis in line 1, Polyptoton, and anadiplosis (in the repetition of mad at the end and start of a phrase): “On purpose laid to make the taker mad;/Mad in pursuit”. But the most obvious and important is the syntactic parallelism that that propels the sonnet after the first quatrain. The technique furiously drives the thematic material forward, line by line, each emphasizing the one before – emphasizing Shakespeare’s angry, remorseful, disappointment in himself – the having and the having had. It all drives the sonnet forward like the blacksmith’s hammer blows on white hot iron.

And when the iron is hot, he strikes:

All this the world well knows; yet none knows well

To shun the heaven that leads men to this hell.

The intellectual power displayed in the rhetorical construction of the sonnet finds its dramatic climax in the final couplet – the antimetabole of “well knows” and “knows well” mirrors the parallelism in the sonnet as a whole – succinctly. The midline break in the first line of the couplet is resolved by the forceful, unbroken final line. The effect is of forceful finality. This sonnet could have been a monologue drawn from one of Shakespeare’s plays. And this, this thematic, dramatic momentum that finds resolution in a final couplet is what most typifies the Shakespearean Sonnet. The form is a showpiece.

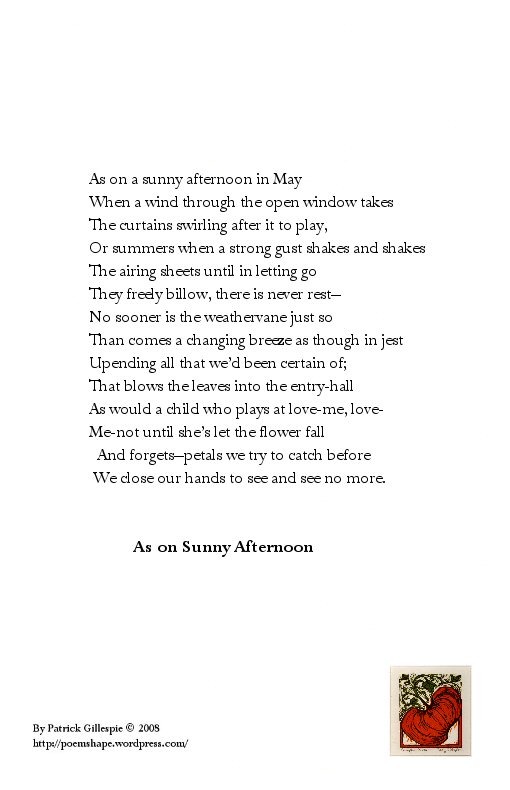

Lastly, I myself have tried my hand at Shakespearean Sonnets. My best effort is “As on a sunny afternoon…”. Three more of my efforts can be found if you look at the top of the banner- under Index: Opening Book (my favorite of the three being The Farmer Wife’s Complaint. I learned how to write poetry by writing Sonnets. I’ve written many others but their quality varies. I may eventually post them anyway.

The Spenserian Sonnet: Spenser’s Sonnet 75

The Spenserian Sonnet: Spenser’s Sonnet 75

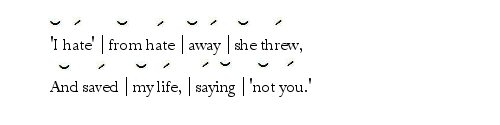

Spenser has to be the most doggedly Iambic of any poet – to a fault. Second only to his dogged metrical Iambs, is his rhyming. English isn’t the easiest language for rhyming (as compared to Japanese or Italian). Rhyming in English requires greater skill and finesse, testing a poet’s resourcefulness and imagination. Yet Spenser rhymed with the ease of a cook dicing carrots. Nothing stopped him. His sonnets reflect that capacity – differing from Shakespeare’s mainly in their rhyme scheme. Here is a favorite Sonnet (to me) his Sonnet 75 from Amoretti:

One day I wrote her name upon the strand,

··But came the waves and washed it away:

··Again I wrote it with a second hand,

But came the tide, and made my pains his prey.

Vain man, said she, that doest in vain assay

··A mortal thing so to immortalize,

··For I myself shall like to this decay,

And eek my name be wiped out likewise.

Not so (quoth I), let baser things devise

··To die in dust, but you shall live by fame:

··My verse your virtues rare shall eternize,

And in the heavens write your glorious name.

··Where whenas Death shall all the world subdue,

··Our love shall live, and later life renew.

The Elizabethans were an intellectually rigorous bunch, which is one of the reasons I enjoy their poetry so much. They don’t slouch or wallow in listless confessionals. They were trained from childhood school days to reason and proceed after the best of the Renaissance rhetoricians. Spenser, like Shakespeare, has an argument to make, but Spenser was less of a dramatist, and more of a lyricist and storyteller. His preference in Sonnet form reflects that. Here it is – the full monty:

The Spenserian Sonnet: Structure

The difference in temperament between Spenser and Shakespeare is revealed in the rhyme scheme each preferred. Spenser was a poet of elegance who looked back at other poets, Chaucer especially; and who wanted his readers to know that he was writing in the grand poetic tradition – whereas Shakespeare was impishly forward looking, a Dramatist first and a Poet second, who enjoyed turning tradition and expectation on its head, surprising his readers (as all Dramatists like to do) by turning Patrarchan expectations upside down. Spenser elegantly wrote within the Petrarchan tradition and wasn’t out to upset any apple carts. Even his choice of vocabulary, as with eek, was studiously archaic (even in his own day).

Spenser’s sonnet lacks the drama of Shakespeare’s. Rather than withholding the couplet until the end of the sonnet, lending a sort of climax or denouement to the form, Spencer dilutes the effect of the final couplet by introducing two internal couplets (smaller brackets on right) prior to the final couplet. While Spencer’s syntactic and thematic development rarely emphasizes the internal couplets, they are registered by the ear and so blunt the effect of the concluding couplet.

There is also less variety of rhyming in the Spenserian Sonnet than in the Shakespearean Sonnet. The effect is of less rigor and momentum and greater lyricism, melodiousness and grace. The rhymes elegantly intertwine not only the quatrains but the octave and sestet (brackets on left). Without being Italian (Petrarchan) the effect which the Spencerian Sonnet produces is more Italian – or at minimum a sort of hybrid between Shakespeare’s English Sonnet and Pertrarch’s “Italian” model.

Spencer comes closest, in spirit, to anything like a Petrarchan Sonnet sequence in the English language.

The Spenserian Sonnet: Spenser’s Meter

As far as I know, Spenser wrote all of his sonnets in Iambic Pentameter. He takes fewer risks than Shakespeare, is less inclined to flex the meter the way Shakespeare does. For instance, in two of the three Shakespeare sonnets I have analyzed on this blog, Shakespeare is willing to have the reader treat heaven as a monosyllabic word (heav’n) (see my post on Shakespeare’s Sonnet 145 for an example of Shakespeare’s usage along with sonnet above). Spencer treats heaven is disyllabic. Their different treatment of the word might reflect a difference in their own dialects but I’m more inclined to think that Shakespeare took a more flexible approach to meter and pronunciation – less concerned than Spenser with metrical propriety. Shakespeare, in all things, was a pragmatist, Spenser, an idealist – at least in his poetry.

(Interesting note, Robert Frost referred to such metrical feet which could be anapestic or Iambic depending on the pronunciation, as “loose Iambs “. Such loose iambs would include Shakespeare’s sonnet where murderous could be pronounced murd’rous and The expense as Th’expense.)

There are two words which the modern reader might pronounce as monosyllabic – washed in line 2 and wiped in line 8. When reading Spenser, it’s best to assume that he meant his lines to be strongly regular. It is thoroughly in keeping with 15th & 16th century poetic practice (and with Spenser especially) to pronounce both words as disyllabic – washèd & wipèd. Spenser was a traditionalist.

I also wanted to briefly draw attention to the difference in Shakespeare and Spenser’s use of figurative language. Shakespeare was much more the intellectual. Nothing in Spenser’s sonnets compare to the brilliant rhetorical figures used by Shakespeare. Shakespeare was a virtuoso on many levels.

The Petrarchan Sonnet: John Milton

The Petrarchan Sonnet: John Milton

The Petrarchan Sonnet was the first Sonnet form to be written in the English Language – brought to the English language by Sir Thomas Wyatt and Henry Howard Earl of Surrey (who was also the first to introduce blank verse to the English writing world). However, there is no great Petrarchan Sonnet sequence that left its mark on the form. The Petrarchan model was quickly superseded by the English/Shakespearean Sonnet. Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Sonnet Sequence (all Petrarchan Sonnets) is mixed with greatness but never influenced the form. They were written toward the close of the form’s long history. For a link to her Sonnets, see below.

The search for the ideal representative, among English language poets, of the Petrarchan Sonnet is a search in vain. Petrarchan Sonnets are scattered throughout the language by a number of great poets and poets, who if they weren’t “great”, happened to write great Petrarchan Sonnets.

One thing I have failed to mention, up to now, is the thematic convention associated with the writing of Sonnets – idealized love. Both the Shakespearean and Spenserian Sonnet sequences play on that convention. The Petrarchan form, interestingly, was readily adopted for other ends. It was as if (since the English Sonnet took over the thematic convention of the Petrarchan sonnet) poets using the Petrarchan form were free to apply it elsewhere.

Since there is no one supreme representative Petrarchan Sonnet or poet, I’ll offer up John Milton’s effort in the form, since it was early on and typifies the sort of thematic freedom to which the Petrarchan form was adapted.

When I consider how my light is spent,

··Ere half my days in this dark world and wide,

··And that one talent which is death to hide

Lodged with me useless, though my soul more bent

To serve therewith my Maker, and present

··My true account, lest He returning chide;

··“Doth God exact day-labor, light denied?”

I fondly ask. But Patience, to prevent

That murmur, soon replies, “God doth not need

Either man’s work or His own gifts. Who best

Bear His mild yoke, they serve Him best. His state

Is kingly: thousands at His bidding speed,

And post o’er land and ocean without rest;

They also serve who only stand and wait.”

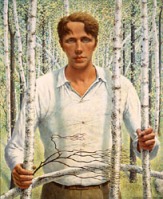

And here is the same Sonnet under the magnifying glass:

The Petrarchan Sonnet: Structure

My primary interest is in English language poets who have written in the Petrarchan form. However, for those who want a good site that examines Petrarchan Sonnets as written by Petrarch, I would strongly recommend Peter Sadlon’s site – he includes some examples in the Italian. He makes the point, for example, that Petrarch did not write Iambic Pentameter sonnets, since the meter is ill-suited to the Italian Language. More important is the observation that Petrarch himself varied the rhyme scheme of the sestet – cd cd cd (as in Milton’s Sonnet), cde ced, or cdcd ee.Petrarch’s freedom in the final sestet is carried over into the English form. You will know that you are reading a Petrarchan sonnet first, if it’s not Shakespearean or Spenserian, and second if the rhyme scheme favors the reading of an octave followed by a sestet. Identifying a Petrarchan sonnet sometimes isn’t an exact science. This beautiful sonnet form is less about the rhyme scheme and more about the tenor of expression.

Interestingly, even though Robert Frost’s famous sonnet “Silken Tent” is formally a Shakespearean Sonnet, it has the feel of a Petrarchan Sonnet.

As regards Milton, he wrote this sonnet as a response to his growing blindness. The sonnet has little to do with idealized love but its meditative and contemplative feel is very much in keeping with Petrarch’s own sonnets – contemplative and meditative poems on idealized love. The rhyme scheme reinforces the the sonnet’s introspection: enforcing the octave, the volta and the concluding sestet.

The internal couplets in the first and second quatrain (smaller brackets on right) give each quatrain and the octave as a whole a self-contained, self-sufficient feeling. The ear doesn’t register a step wise progression (a building of momentum) as it does in the Shakespearean & Spenserian models. The effect is to create a kind of two-stanza poem rather than the unified working-out of the English model.

Note: Perhaps a useful way to think of the difference between the Petrarchan and Shakespearean Sonnets is to think of the Petrarchan form as a sonnet of statement and the Shakespearean form as a sonnet of argument. Be forewarned, though, this is just a generalization with all its inherent limitations and exceptions.

The volta or turn comes thematically with God’s implied answer to Milton’s questioning. The lack of the concluding couplet makes the completion of the poem less epigrammatic, less dramatic and more considered. The whole is a sort of perfectly contained question and answer.

The Petrarchan Sonnet: Milton’s Meter

This sonnet was written prior to Paradise Lost and, to my ear, shows a slightly more adventurous metric. The first departure from the iambic rhythm comes in the first foot of line 4 with Lodged. This is the sort variation that perfectly exploits the expectations established by a metrical pattern. That is, the word works on two levels, “lodged” thematically and trochaic-ally within the iambic meter- not a brilliant variant but an effective one.

In line 5 I read the fourth foot as being pyrric, but one can also give the word and an intermediate stress: To serve therewith my Maker, and present.

It’s not until line 11 that things get interesting. Most modern readers would probably read the first two feet of the line as follows:

Bear His |mild yoke, |they serve Him best. His state

But the line can be read another way – iambically. And in poetry of this period, if we can, then we should.

Bear His |mild yoke, |they serve Him best. His state

What’s lovely about this reading, which is what’s lovely about meter, is that the inflection and meaning of the line changes. Notice also how His is emphasized in the first foot, but isn’t in the fourth and fifth:

Bear His |mild yoke, |they serve |Him best. |His state

In this wise, the emphasis is first on God, then on serving him. It is a thematically natural progression.

The last feature to notice is that the final line, line 14, retains a little of the pithy epigrammatic quality of the typical English or Shakespearean Sonnet. No form or genre is completely isolated from another. The Petrarchan mode can be felt in the Shakespearean Sonnet and the Shakespearean model can be felt in the Petrarchan model.

The Miltonic Sonnet

The Miltonic Sonnet is a Petrarchan Sonnet without a volta. Although Milton was hardly the first to write sonnets in English without a volta, Shakespeare’s Sonnet 129 being a case in point, Milton made that absence standard practice; and so, this variation on the Petrarchan Sonnet is called a Miltonic Sonnet.

On the Importance of Naming Things

Not only are there names for the different sonnets, which is forgivable, but there also names for the different quatrains and octaves in all these sonnets because human beings like nothing more than to classify. God’s first request to Adam & Eve was to name… everything. (What interests me more is puzzling out the aesthetic effects these different rhyme schemes produce.) But, because knowing the name of things always sounds impressive – here they are.

Petrarchan

The Petrarchan Sonnet can be said to be written with two Italian Quatrains (abbaabba) which together are called an Italian Octave.

The Italian Octave can be followed by an Italian Sestet (cdecde) or a Sicilian Sestet (cdcdcd)

The Envelope Sonnet, which is a variation on the Petrarchan Sonnet, rhymes abbacddc efgefg or efefef.

Shakespearean

The Shakespearean Sonnet is written with three Sicilian Quatrains: (abab cdcd efef) followed by a heroic couplet. Note, the word heroic refers to Iambic Pentameter. Heroic couplets are therefore Iambic Pentameter Couplets. However, not all Elizabethan Sonnets are written in Iambic Pentameter.

Spenserian

The Spenserian Sonnet is written with three interlocking Sicilian Quatrains: (abab bcbc cdcd) followed by a heroic couplet.

- Note: I have found no references which reveal when these terms first came into use. I doubt that the terms Sicilian or Italian Quatrain existed in Elizabethan times. Spenser didn’t sit down and say to himself: Today, I shall write interlocking sicilian quatrains. I think it more likely that these poets chose a given rhyme scheme because they were influenced by others or because the rhyme scheme was most suitable to their aesthetic temperament.

- Note: It bears repeating that many books on form will state that all these sonnets are characterized by voltas. They are, emphatically, not. Shakespeare’s Sonnet 129 (above) would be an example.

Sidneyan Sonnet

Other Petrarchan Sonnets

Since the Petrarchan Sonnet is so varied in the English Language tradition, I thought I would post a few more examples. I have divided the quatrains, octaves and sestets to better show their structure. I’ll probably come back to this post and include more as I find them. (For the most part, a couplet in the closing sestet seems, usually, to be avoided by most poets.)

John Keats

Rhyme Scheme:

ABBA ABBA CDCDCD (The same as Milton’s)

On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer

Much have I travell’d in the realms of gold,

Much have I travell’d in the realms of gold,

And many goodly states and kingdoms seen;

Round many western islands have I been

Which bards in fealty to Apollo hold.

Oft of one wide expanse had I been told

That deep-brow’d Homer ruled as his demesne;

Yet did I never breathe its pure serene

Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold:

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He star’d at the Pacific–and all his men

Look’d at each other with a wild surmise

Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

William Wordsworth

Rhyme Scheme:

ABBA ACCA DEDEDE

Surprised by joy — impatient as the Wind

Surprised by joy — impatient as the Wind

I turned to share the transport–Oh! with whom

But Thee, deep buried in the silent tomb,

That spot which no vicissitude can find?

Love, faithful love, recalled thee to my mind–

But how could I forget thee? Through what power,

Even for the least division of an hour,

Have I been so beguiled as to be blind

To my most grievous loss?–That thought’s return

Was the worst pang that sorrow ever bore,

Save one, one only, when I stood forlorn,

Knowing my heart’s best treasure was no more;

That neither present time, nor years unborn

Could to my sight that heavenly face restore.

Percy Bysshe Shelley

Rhyme Scheme:

ABAB ACDC EDEFEF

I met a traveller from an antique land

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: “Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. Near them on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown

And wrinkled lip and sneer of cold command

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed.

And on the pedestal these words appear:

`My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings:

Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!’

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare,

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

For a closer look at this sonnet, take a look at my post: Shelley’s Sonnet: Ozymandias

Edna St. Vincent Millay

Rhyme Scheme:

ABBA ABBA CDEDCE

What lips my lips have kissed, and where, and why,

What lips my lips have kissed, and where, and why,

I have forgotten, and what arms have lain

Under my head till morning; but the rain

Is full of ghosts tonight, that tap and sigh

Upon the glass and listen for reply,

And in my heart there stirs a quiet pain

For unremembered lads that not again

Will turn to me at midnight with a cry.

Thus in winter stands the lonely tree,

Nor knows what birds have vanished one by one,

Yet knows its boughs more silent than before:

I cannot say what loves have come and gone,

I only know that summer sang in me

A little while, that in me sings no more.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning

Rhyme Scheme:

ABBA ABBA CDCDCD

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of Being and ideal Grace.

I love thee to the level of everyday’s

Most quiet need, by sun and candle-light.

I love thee freely, as men strive for Right;

I love thee purely, as they turn from Praise.

I love thee with a passion put to use

In my old griefs, and with my childhood’s faith.

I love thee with a love I seemed to lose

With my lost saints, — I love thee with the breath,

Smiles, tears, of all my life! — and, if God choose,

I shall but love thee better after death.

Other Sonnets:

- Sir Philip Sidney Astrophel and StellaSidney’s sonnets are a kind of hybrid between the Shakespearean and Petrarchan mode. The Octave of his sonnets alternate between the Petrarchan Octave and the interlocking Sicilian Quatrains of the English Sonnets. His Sestets alternate between one of his own devising and the Shakespearean model. For more on this: visit my post Sidney: His Meter and Sonnets.

- John Donne Holy Sonnets These sonnets are like Sidney’s – having qualities of both the Shakespearean and Petrarchan form.

- And then there are sonnets of varying rhyme schemes – Nonce Sonnets. The word Nonce simply means that a given form is unique to the poem. Keats’ If by dull rhymes would be a Nonce Sonnet – and written specifically about the making of a new rhyme scheme.

John Keats

Rhyme Scheme:

ABCADE CADC EFEF

If by dull rhymes our English must be chain’d,

And, like Andromeda, the Sonnet sweet

Fetter’d, in spite of pained loveliness;

Let us find out, if we must be constrain’d,

Sandals more interwoven and complete

To fit the naked foot of poesy;

Let us inspect the lyre, and weigh the stress

Of every chord, and see what may be gain’d

By ear industrious, and attention meet:

Misers of sound and syllable, no less

Than Midas of his coinage, let us be

Jealous of dead leaves in the bay wreath crown;

So, if we may not let the Muse be free,

She will be bound with garlands of her own.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

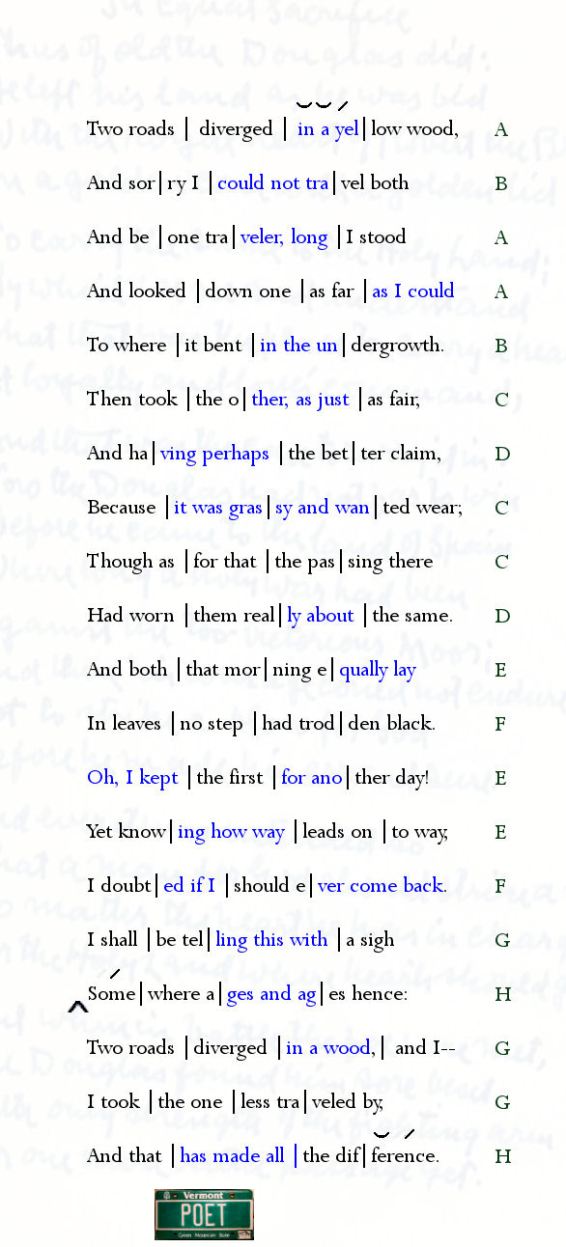

Interestingly, Frost reads the fifth line as follows:

Interestingly, Frost reads the fifth line as follows:

sacrifice the “sound of sense” for the sake of meter. But he also strikes a balance. Once again, notice that he brackets this line with perfectly Iambic Pentameter lines before and after. In the 9th line, he substitues an anapestic final foot for an iambic foot – a much freer variation than used by any poet in the generation preceeding him.

sacrifice the “sound of sense” for the sake of meter. But he also strikes a balance. Once again, notice that he brackets this line with perfectly Iambic Pentameter lines before and after. In the 9th line, he substitues an anapestic final foot for an iambic foot – a much freer variation than used by any poet in the generation preceeding him.

The first three lines, metrically, are alike. They seem to establish a metrical pattern of two iambic feet, a third anapestic foot, followed by another iambic foot.

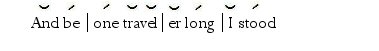

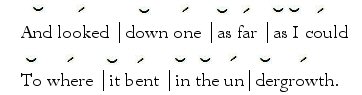

The first three lines, metrically, are alike. They seem to establish a metrical pattern of two iambic feet, a third anapestic foot, followed by another iambic foot. This is not an unreasonable way to scan the poem – but it ignores how Frost himself read it. And in that respect, and only in that respect, their scansion is wrong. Furthermore, even without Frost’s authority, their reading ignores Iambic meter. Frost puts the emphasis on trav-eler and so does the meter. Their reading also ignores or fails to observe the potential for elision in trav‘ler which, to be honest, is how most of us pronounce the word. A dactyllic reading is a stretch. I think, at best, one might make an argument for the following:

This is not an unreasonable way to scan the poem – but it ignores how Frost himself read it. And in that respect, and only in that respect, their scansion is wrong. Furthermore, even without Frost’s authority, their reading ignores Iambic meter. Frost puts the emphasis on trav-eler and so does the meter. Their reading also ignores or fails to observe the potential for elision in trav‘ler which, to be honest, is how most of us pronounce the word. A dactyllic reading is a stretch. I think, at best, one might make an argument for the following:

The second quintain’s line continues the metrical pattern of the first lines but soon veers away. In the second and third line of the quintain, the anapest variant foot occurs in the second foot. The fourth line is one of only three lines that is unambiguously Iambic Tetrameter. Interestingly, this strongly regular line comes immediately after a line containing two anapestic variant feet. One could speculate that after varying the meter with two anapestic feet, Frost wanted to firmly re-establish the basic Iambic Tetrameter pattern from which the overal meter springs and varies.

The second quintain’s line continues the metrical pattern of the first lines but soon veers away. In the second and third line of the quintain, the anapest variant foot occurs in the second foot. The fourth line is one of only three lines that is unambiguously Iambic Tetrameter. Interestingly, this strongly regular line comes immediately after a line containing two anapestic variant feet. One could speculate that after varying the meter with two anapestic feet, Frost wanted to firmly re-establish the basic Iambic Tetrameter pattern from which the overal meter springs and varies.

Sorrow like a ceaseless rain

Sorrow like a ceaseless rain

As far as this soliloquy goes, there’s a surplus of good online analysis. And if you’re a student or a reader then you probably have a book that already provides first-rate annotation. The only annotation I haven’t found (which is probably deemed unnecessary by most) is an analysis of the blank verse – a scansion – along with a look at its rhetorical structure. So, the post mostly reflects my own interests and observations – and isn’t meant to be a comprehensive analysis. If any of the symbols or terminology are unfamiliar to you check out my posts on

As far as this soliloquy goes, there’s a surplus of good online analysis. And if you’re a student or a reader then you probably have a book that already provides first-rate annotation. The only annotation I haven’t found (which is probably deemed unnecessary by most) is an analysis of the blank verse – a scansion – along with a look at its rhetorical structure. So, the post mostly reflects my own interests and observations – and isn’t meant to be a comprehensive analysis. If any of the symbols or terminology are unfamiliar to you check out my posts on

Emily Dickinson possessed a genius for figurative language and thought. Whenever I read her, I’m left with the impression of a woman who was impish, insightful, impatient, passionate and confident of her own genius. Some scholars portray her as being a revolutionary who rejected (with a capital R) the stock forms and meters of her day.

Emily Dickinson possessed a genius for figurative language and thought. Whenever I read her, I’m left with the impression of a woman who was impish, insightful, impatient, passionate and confident of her own genius. Some scholars portray her as being a revolutionary who rejected (with a capital R) the stock forms and meters of her day.

The Spenserian Sonnet: Spenser’s Sonnet 75

The Spenserian Sonnet: Spenser’s Sonnet 75

The Petrarchan Sonnet: John Milton

The Petrarchan Sonnet: John Milton

Much have I travell’d in the realms of gold,

Much have I travell’d in the realms of gold, Surprised by joy — impatient as the Wind

Surprised by joy — impatient as the Wind I met a traveller from an antique land

I met a traveller from an antique land What lips my lips have kissed, and where, and why,

What lips my lips have kissed, and where, and why,

Those lips that Love’s own hand did make

Those lips that Love’s own hand did make