- September 28 2011: Be sure and read the comment section, especially the comments by Richard Lawrence, who shares with us a seemingly lost verse from the original version of this poem.

- July 18, 2009: New Post – Robert Frost’s “Out, Out”

- June 6 2009: Tweaked and expanded.

About the Pasture

I’ve been following the lead of my readers, noting on the Stats page what searches you use to find my blog. The most popular poet remains Robert Frost. And I’ve noticed several searches for Frost’s “The Pasture”.

Robert Frost recites The Pasture

There are few poems in the English language that can compare. Right now? I can’t think of one. In terms of brevity and memorability, it’s unsurpassed. Why? Subject matter, rhyme and meter are perfectly suited to each other.

Robert Frost himself, according to Lea Newman (book at left), stated that it was “a poem about love that’s new in treatment and effect. You won’t find anything in the range of English poetry just like that.”

Robert Frost himself, according to Lea Newman (book at left), stated that it was “a poem about love that’s new in treatment and effect. You won’t find anything in the range of English poetry just like that.”

I have several books on Robert Frost and all of them only mention this poem in passing – giving it short shrift. Lea Newman’s book, in terms of the poems themselves, remains the best of any of them. Her opening paragraph describes some of the inspiration for the poem:

One spring evening in 1905, Frost took a walk over those fields with his wife, Elinor, and their six-year-old daughter, Lesley. According to the notebook Lesley kept as a child, she and her mother picked apple and strawberry blossoms while her father went down to the southwest corner of the big cow pasture to check on how much water was in the spring. In 1910, when Frost wrote “The Pasture” he used a walk to a spring in a cow pasture as its centerpiece. The experience was still a favorite memory thirty years after he wrote about it. In 1940 he reminisced, “I never had a greater pleasure that coming on a neglected spring in a pasture in the woods.

Newman’s introduction to the poem continues and I wholly recommend the book as a companion to his poems. But what does the poem mean? (It never seems enough to say that the poem means what it says.) It’s a poem of invitation first and foremost – Frost chose this poem as a sort of introduction and invitation to his collected poems. More than that, the poem typifies what many readers love the most about Frost: his connectedness with nature and the everyday; his contemplative ease; and, above all, the approachable content of his thought and poetry. Frost was a poet with whom most everyone felt a kinship and understanding. He was comprehensible during a time when poetry was becoming increasingly incomprehensible. Saying he won’t be gone long could summarize his craft. There are depths to his poetry, but they are such that the reader returns. He won’t go too far. He won’t be gone too long. You come too, he says to the reader and to anyone who wants to go with him.

Meter and Rhyme

The internal rhyme that contributes to the poems lyricism is the most important and also the most difficult to describe, but I’ll try. And it may seem like I’m making too much of vowel sounds, but sound is everything in poetry. Consider the following anecdote which occurred between Keats and Wordsworth (from John Keats: His Life and Poetry, His Friends, Critics and After-Fame by Sidney Colvin pp. 401-402):

And here is another sample about Keats’s as related by his friend, Benjamin Bailey:

…one of Keats’ favorite topics of conversation was the principle of melody of verse, which he believed to consist in the adroit management in verse, which he believed to consist in the adroit management of open and close vowels. He had a theory that vowels could be as skillfully combined and interchanged as as differing notes of music, and that all sense of monotony was to be avoided, except when expressive of a special purpose. (Richard H. Fogle – The Imagery of Keats and Shelley, p. 63)

In point of a fact, I write my own poetry with the vowel sounds in mind. I hear words as music and tones, which makes me an “ear reader” rather than an “eye reader”, as Frost put it, and a very slow reader.

Keats was conscious of his choices, and Frost was too. (However, it’s definitely possible to read too much into “word sounds”, vowel sounds, percussive consonants and the like – I’ve seen it done by plenty of critics and analysts.) Such analytic overreaches are called Enactment Fallacies – a term I first came across in one of David Orr’s New York Times reviews. He defines it: in the following passage:

Basically, this is the assignment of meaning to technical aspects of poetry that those aspects don’t necessarily possess. For example, in an otherwise excellent discussion of Yeats’s use of ottava rima (a type of eight-line stanza), Vendler attributes great effect to “the pacing” allegedly created by “a fierce set of enjambments” followed by a “violent drop” in the fourth stanza of the poem “Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen.” Here’s the stanza in question:

Now days are dragon-ridden, the nightmare

Rides upon sleep: a drunken soldiery

Can leave the mother, murdered at her door,

To crawl in her own blood, and go scot-free;

The night can sweat with terror as before

We pieced our thoughts into philosophy,

And planned to bring the world under a rule,

Who are but weasels fighting in a hole.“With each new verbal or participial theater of action of the stanza, there arrives a new agent,” Vendler writes, “making the clauses scramble helter-skelter, one after the other. The headlong pace is crucial.” Since the stanza involves words like “dragon,” “nightmare,” “murdered,” “blood” and “fighting,” it’s easy to see what she’s thinking here. But to make a more modest use of Vendler’s rewriting trick above, what if we kept the same enjambments, syntax, rhyme scheme and basic rhythm — yet changed some of the words? We might get this (my words, with apologies to I. A. Richards for adapting one of his tactics):

Now days are slow and easy, the summer

Sighs into fall: a purring bumble-bee

Can leave the flower, softened to a blur,

To soak in the noon sun, and fly carefree;

The night can breathe with pleasure as once more

We weave our visions into poetry

And seek to bring our thoughts under a rule,

Who are the mindful servants of the soul.Not so “helter-skelter” now, is it? In a book review or essay, committing this particular fallacy is a minor error. Most critics do it regularly (I certainly have). In a book that sets out to explain why a poet makes particular formal choices, however, the mistake is more serious, because it replaces the complex relationships among a poem’s elements with just-so stories in which it always turns out — surprise! — that meaning has been mirrored by shape and sound. Think of it this way: we don’t enjoy a bowl of gumbo because it “feels” exactly the way it “tastes”; rather, we find the combination of “taste” and “feel” pleasing. Similarly, a particular stanza arrangement can reinforce our experience of a poem, but only because that arrangement is working in harmony with the poem’s other aspects.

I quote the better part of the passage because I think it’s something every novice in poetry and poetry criticism should be aware of. Read all criticism and analysis with skepticism. Including, obviously, mine; though I try to be reasonable in my assertions.

Anyway, back to Frost and The Pasture. Whether intentional or not, the first line’s variety of vowel sounds is lovely – no two are repeated.

I’m going out to clean the pasture spring;

That in itself isn’t so remarkable, but what happens next, to me at least, beautifully sets off the first line.

I’ll only (stop) to rake the leaves (a) way

(And wait to (watch) the (wa)ter clear, I may) :

The two lines are rich with internal rhyme – the long A’s of rake, away, wait and may bracket the short, rhyming vowel sounds of stop, away, watch and water.  The effect of these internal rhymes (interlocking in the second line and bracketed in the third) will be different for different readers, though I think all readers, but those with tin ears, will register them. To me the internal rhyming creates a sort of sing-song effect in perfect keeping with the light-hearted, carefree, teasing tone of the poem. And, again for me, the “long A” vowel sound has a sort of easy-going and open feel to it. There’s no way to know whether Frost had this in mind, but I’m sure that the music in the lines, however he interpreted their effect, was intended.

The effect of these internal rhymes (interlocking in the second line and bracketed in the third) will be different for different readers, though I think all readers, but those with tin ears, will register them. To me the internal rhyming creates a sort of sing-song effect in perfect keeping with the light-hearted, carefree, teasing tone of the poem. And, again for me, the “long A” vowel sound has a sort of easy-going and open feel to it. There’s no way to know whether Frost had this in mind, but I’m sure that the music in the lines, however he interpreted their effect, was intended.

I sha’n’t be gone long. (You) come (too).

Up to this point, the lines have been Iambic Pentameter. But the fourth line (repeated in the second stanza) is Iambic Tetrameter. The effect is lovely and though it can be imitated in free verse, it can’t be reproduced.

The first three lines could be spoken to an unnamed companion or to oneself. We read the poem in the same manner that we read first person narratives (where our presence is irrelevant to the narrator). But then Frost does something magical. He talks explicitly to “you” and he does so in Iambic Tetrameter. “You come too”, he says, and the shortened tetrameter line has same effect as an aside in a play or drama – an effect of immediacy and personableness. Suddenly we find ourselves in the poem!

The internal rhyme of gone and long anticipate and are complimented by You and too. The musicality of the line heightens the feeling of intimacy, unselfconsciously inviting – the appeal of a close friend. And, as a final note, notice too how the Iambic pattern is broken in the last two feet (spondaic variant feet) of the Tetrameter line.

I sha’n’t |be gone |long. You |come too.

This too adds to the air of informality. The formal Iambic Pentameter is broken for the sake of a friendly aside. The ceasura (the break between the two sentences), occurs in the middle of the third foot, also disrupting the metrical pattern of the previous lines. It all contributes to the informal, intimate feel of the fourth line. Again, it’s an effect that free verse simply can’t equal.

Frost’s Colloquialisms

One of Robert Frost’s most powerful poetic figures (as in a rhetorical figure or figure of speech – also called figurative language) is anthimeria. It’s also one of my favorites and one of the truly beautiful ornaments in the toolbox of poetry – adding vitality and rigorousness when done well. (Shakespeare was one of the greatest users of this figure.) In short, anthimeria is the substitution of one part of speech for another – “when adjectives are used as adverbs, prepositions as adjectives, adjectives as nouns, nouns as adjectives” (Shakespeare’s Use of the Arts of Language p. 63) . Turning nouns into adjectives is Frost’s favorite substitution and he does this because, interestingly, this form of grammatical substitution is typical of New England dialects. (For a more thorough treatment of colloquialism in poetry, see my post Vernacular Colloquial Common Dialectal.)

One of Robert Frost’s most powerful poetic figures (as in a rhetorical figure or figure of speech – also called figurative language) is anthimeria. It’s also one of my favorites and one of the truly beautiful ornaments in the toolbox of poetry – adding vitality and rigorousness when done well. (Shakespeare was one of the greatest users of this figure.) In short, anthimeria is the substitution of one part of speech for another – “when adjectives are used as adverbs, prepositions as adjectives, adjectives as nouns, nouns as adjectives” (Shakespeare’s Use of the Arts of Language p. 63) . Turning nouns into adjectives is Frost’s favorite substitution and he does this because, interestingly, this form of grammatical substitution is typical of New England dialects. (For a more thorough treatment of colloquialism in poetry, see my post Vernacular Colloquial Common Dialectal.)

So…

Instead of saying “I’m going out to clean the spring in the pasture”, he says “pasture spring”. Pasture, normally a noun, becomes an adjective modifying spring. Et viola! Anthimeria! If you read enough of Frost’s poetry you will see this figurative language recur again and again. And if you hang about Vermont, New Hampshire or Maine, and hear some old-timers, you will hear this same grammatical short-cut. I don’t know why it’s more prevalent in New England (more so than in other regions of the United States) but it may be a hold over from the speech patterns of a much older generation.

Anyway, Frost always keenly observed, recorded and remembered the speech habits of New Englanders and deliberately infused his own poetry with the patterns he heard. Techniques like anthimeria, the substitution of a noun for an adjective, helps give his poetry a dailectal and colloquial feel. In a similar vein, the contraction sha’n’t, for shall not, adds to the colloquial informality and intimacy of the poem. “I sha’n’t be gone long” is a style of speech that’s almost gone. Probably more typical of what was heard among an older generation of New Englanders if only because the region is where American English is the oldest.

I’m going out to fetch the little (calf)

That’s (stand)ing by the mother. It’s so young,

It totters when she licks it with her tongue.

I (sha’n’t) be gone long. You come too.

Again, I’ve tried to emphasize the play of internal rhyme – to make it visible. The short i sound of little is bolded. The short a sound of calf is italicized and (bracketed). The short u sound of young is underlined. I won’t belabor the same points I’ve already made discussing the previous stanza. The effects are the same. There are no internal rhymes within the first line of the stanza, as in the first line of the first stanza. The sing-song informality and intimacy created by the internal rhymes that occur in the lines that follow, once again, find completion and resolution in the final invitation:

You come too.

If this post has been helpful to you; if you enjoyed; if you have suggestions or questions; please comment!

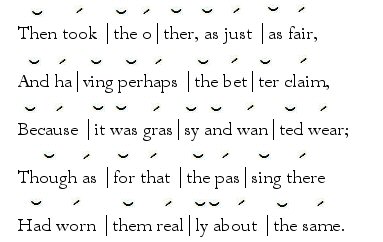

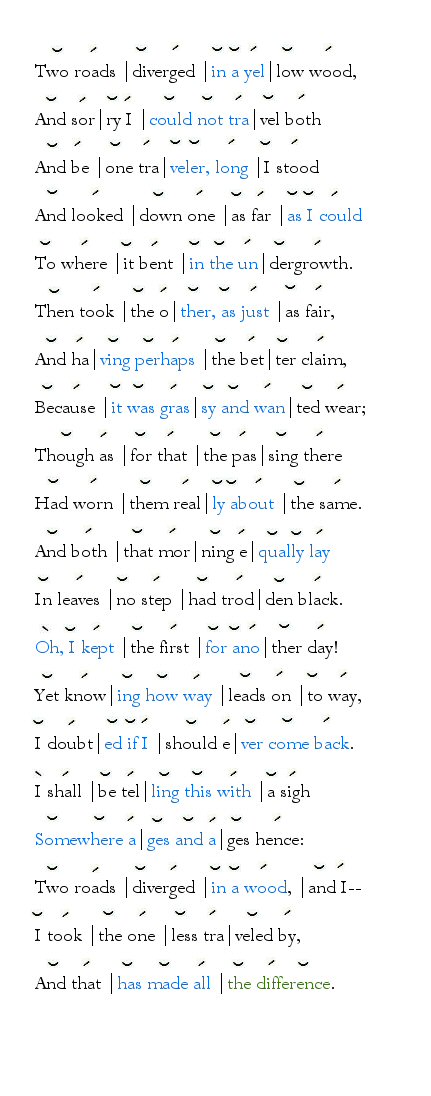

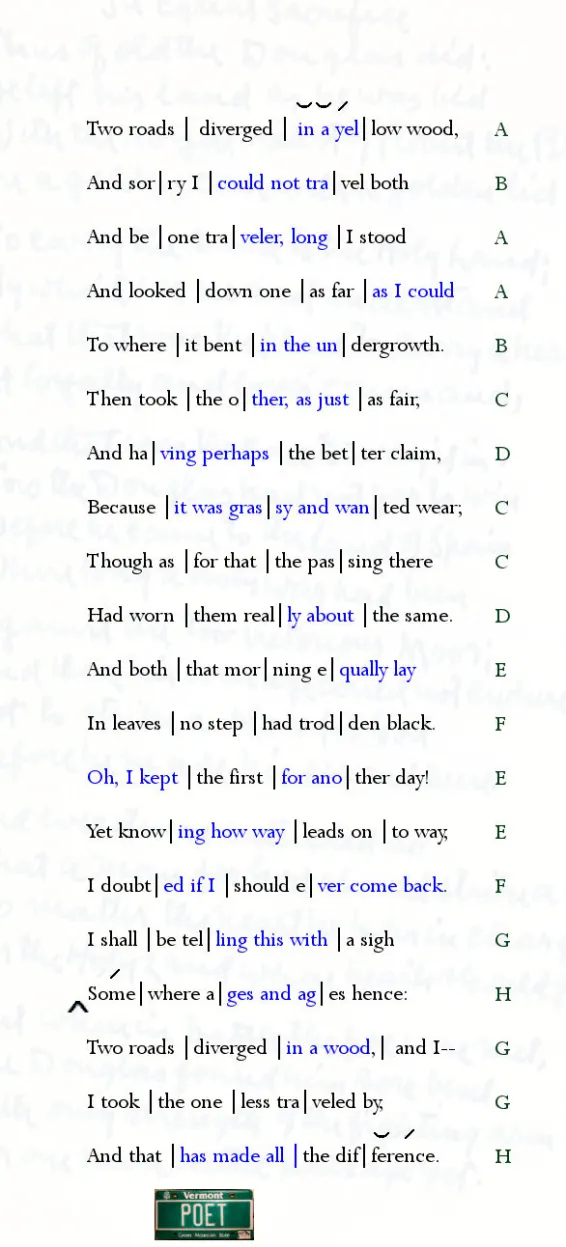

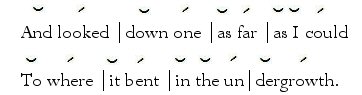

The first three lines, metrically, are alike. They seem to establish a metrical pattern of two iambic feet, a third anapestic foot, followed by another iambic foot.

The first three lines, metrically, are alike. They seem to establish a metrical pattern of two iambic feet, a third anapestic foot, followed by another iambic foot. This is not an unreasonable way to scan the poem – but it ignores how Frost himself read it. And in that respect, and only in that respect, their scansion is wrong. Furthermore, even without Frost’s authority, their reading ignores Iambic meter. Frost puts the emphasis on trav-eler and so does the meter. Their reading also ignores or fails to observe the potential for elision in trav‘ler which, to be honest, is how most of us pronounce the word. A dactyllic reading is a stretch. I think, at best, one might make an argument for the following:

This is not an unreasonable way to scan the poem – but it ignores how Frost himself read it. And in that respect, and only in that respect, their scansion is wrong. Furthermore, even without Frost’s authority, their reading ignores Iambic meter. Frost puts the emphasis on trav-eler and so does the meter. Their reading also ignores or fails to observe the potential for elision in trav‘ler which, to be honest, is how most of us pronounce the word. A dactyllic reading is a stretch. I think, at best, one might make an argument for the following:

The second quintain’s line continues the metrical pattern of the first lines but soon veers away. In the second and third line of the quintain, the anapest variant foot occurs in the second foot. The fourth line is one of only three lines that is unambiguously Iambic Tetrameter. Interestingly, this strongly regular line comes immediately after a line containing two anapestic variant feet. One could speculate that after varying the meter with two anapestic feet, Frost wanted to firmly re-establish the basic Iambic Tetrameter pattern from which the overal meter springs and varies.

The second quintain’s line continues the metrical pattern of the first lines but soon veers away. In the second and third line of the quintain, the anapest variant foot occurs in the second foot. The fourth line is one of only three lines that is unambiguously Iambic Tetrameter. Interestingly, this strongly regular line comes immediately after a line containing two anapestic variant feet. One could speculate that after varying the meter with two anapestic feet, Frost wanted to firmly re-establish the basic Iambic Tetrameter pattern from which the overal meter springs and varies.