- Sept 22, 2009 • Just learned that Jane Campion has made a movie “based” on the relationship between John Keats and Fanny Brawne. You can watch the trailer at the bottom of the post.

About the Poem

I have two luxuries to brood over in my walks, your loveliness and the hour of my death. O that I could have possession of them both in the same minute. – John Keats in a letter to Fanny Brawne

Bright Star is one of Keats’s earlier poems and I can’t help but detect the opening of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 116.

Let me not to the marriage of true minds

Admit impediments. Love is not love

Which alters when it alteration finds,

Or bends with the remover to remove:

O no! it is an ever-fixed mark

That looks on tempests and is never shaken;

It is the star to every wandering bark,

Whose worth’s unknown, although his height be taken.

Shakespeare equates love to a star and this association was surely present in Keats’ mind from the time he first read Shakespeare’s Sonnet. That is, the star isn’t only a symbol of steadfastness and stability, but also love. And love, in Keats’s mind, is unchangeable and ever-fixèd (or else it isn’t love). Shakespeare’s Ever-fixèd turns into Keats’ steadfast. Shakespeare’s never shaken turns into Keats’s hung aloft the night and unchangeable. R.S. White, in his book Keats as a reader of Shakespeare, makes note of some other parallels as well:

…it is not possible to ignore a creative connection between Keats’s resonant line, “Bright Star, would I were stedfast as thou art–‘ and on the one hand the phrase of the undoubtedly ‘stedfast’ character, Helena,

‘Twere all one,

That I should love a bright particular star, (I.i.79-80)and on the other, although the play is not marked, Julius Ceasar’s more ironic ‘But I am constant as the northern star’ (Julius Ceasar, III.i.60). Such echoes, whether intende, unconcious or even coincidental, display vividly the special compatibility between the language and thought of Keats and the parts of Shakespeare which he appreciated and assimilated so thoroughly. [p. 72]

White’s survey of Keats’ Shakespearean influence isn’t just guess work by the way. Keats’ copy of Shakespeare’s plays is still extent, along with his comments, underlinings and double-underlinings. White’s book is an interesting commentary on Keats’ reading of Shakespeare. White observes another interesting parallel between Shakespeare and Keats’ poetic thought:

[Keats] picks out one of the images in the [Midsummer Night’s Dream] to convey his enthusiasm for Shakespeare’s poetry of the sea, which he often equates with Shakespeare himself:

Which is the best of Shakespeare’s Plays? – I mean in what mood and with what accompaniment do you like the Sea best? It is very fine in the morning when the Sun

‘opening on Neptune with fair blessed beams

Turns into yellow gold his salt sea streams’Keats seems to be trusting his memory for the quotation, for his ‘salt sea’ is actually ‘salt green (II.ii.329-3). By associating Shakespeare himself with the moods of the sea, Keats is perhaps conveying something of his notion of the dramatist’s developement, implying that after the morning of this play the sea will become rougher as the day goes on. Shakespeare’s sea-music informs Keats’s poetry as well, particularly in the sonnets ‘On the Sea’ and ‘Bright Star’. [p. 102]

What White doesn’t mention are the parallels between Keats’ Sonnet and Shakespeare’s. Notice how the sea makes it’s appearance in both sonnets.

…it is an ever-fixed mark

That looks on tempests and is never shaken;

It is the star to every wandering bark…

Compared to Keats

…watching, with eternal lids apart,

Like nature’s patient, sleepless Eremite,

The moving waters at their priestlike task

Of pure ablution round earth’s human shores…

And there are also some parallels in Keats’ letters that remind one of the Sonnet’s central themes.  The most explicit, in terms of thematic content, comes from May 3, 1818, in a letter to his fiance Fanny Brawne.

The most explicit, in terms of thematic content, comes from May 3, 1818, in a letter to his fiance Fanny Brawne.

“. . .I love you; all I can bring you is a swooning admiration of your Beauty. . . . You absorb me in spite of myself–you alone: for I look not forward with any pleasure to what is call’d being settled in the world; I tremble at domestic cares–yet for you I would meet them, though if it would leave you the happier I would rather die than do so. I have two luxuries to brood over in my walks, your Loveliness and the hour of my death. O that I could have possession of them both in the same minute. I hate the world: it batters too much the wings of my self-will, and would I could take a sweet poison from your lips to send me out of it. From no others would I take it. I am indeed astonish’d to find myself so careless of all charms but yours–remembering as I do the time when even a bit of ribband was a matter of interest with me. What softer words can I find for you after this–what it is I will not read. Nor will I say more here, but in a Postscript answer any thing else you may have mentioned in your Letter in so many words–for I am distracted with a thousand thoughts. I will imagine you Venus tonight and pray, pray, pray to your star like a Hethen.”

Love letters don’t get much better than this and Keats’ Sonnet is thought to be a love poem to Fanny Brawne – and  Brawne herself treated it as such. She copied Bright Star into her “very dear gift” of Dante’s Inferno – along with its thematically related (but much less successful) companion sonnnet As Hermes once took his feathers light (see below). Anyway, worth noting is his comparison of Brawne to a star and his desire, as in the poem, to “swoon to death” or, as he puts it – “I could take a sweet poison from your lips to send me out of it.” The play of death and orgasm shouldn’t be overlooked in all this romantic swooning. The conceit is probably as old as sex and, Keats, if nothing else, was an über sensualist. If tuberculosis hand’t killed him, sex probably would have.

Brawne herself treated it as such. She copied Bright Star into her “very dear gift” of Dante’s Inferno – along with its thematically related (but much less successful) companion sonnnet As Hermes once took his feathers light (see below). Anyway, worth noting is his comparison of Brawne to a star and his desire, as in the poem, to “swoon to death” or, as he puts it – “I could take a sweet poison from your lips to send me out of it.” The play of death and orgasm shouldn’t be overlooked in all this romantic swooning. The conceit is probably as old as sex and, Keats, if nothing else, was an über sensualist. If tuberculosis hand’t killed him, sex probably would have.

There are still some more interesting parallels. Amy Lowell, in her biography on Keats called John Keats, argues that during a visit to a Mrs. Bentley’s, Keats writes to George (his brother) that he ” put all the letters to and from you and poor Tom and me…” [Book II, p. 202] In one of these letters, which Lowell argues Keats must have reread, comes the following:

“We are now about seven miles from Rydale, and expect to see [Wordsworth] to-morrow. You shall hear all about our visit .

There are many disfigurements to this Lake — not in the way of land or Water. No; the two views we have had of it are of the most noble tenderness – they can never fade away – they make one forget the divisions of life; age, youth, poverty and riches; and refine one’s sensual vision into a sort of north star which can never cease to be open lidded and stedfast over the wonders of the great Power…” [Book II, p. 22]

As Lowell points out, the parallels are too uncanny. It doesn’t take much to go from, a sort of north star which can never cease to be open lidded and stedfast over the wonders of the great Power, to:

Not in lone splendour hung aloft the night

And watching, with eternal lids apart,

Like nature’s patient, sleepless Eremite,

Bright star, would I were stedfast as thou art–

If Keats didn’t lift from having re-read an older letter, then the imagery linking the open lidded eye with the North Star, the one constant star of the sky, was certainly ever fixed in his mind. All poets, and this is something I would like to write more about, reveal a habit of thought, imagery and associations over the course of their careers. The great poets vary them, the competent poets don’t.

Yet another anecdote is related by another of Keats’s biographers, Aileen Ward. She notes that while writing a letter, Keats saw Venus rising outside his window. Ward says that at that moment all “doubt and distraction left him; it was only beauty, Fanny’s and the star’s, that mattered.”

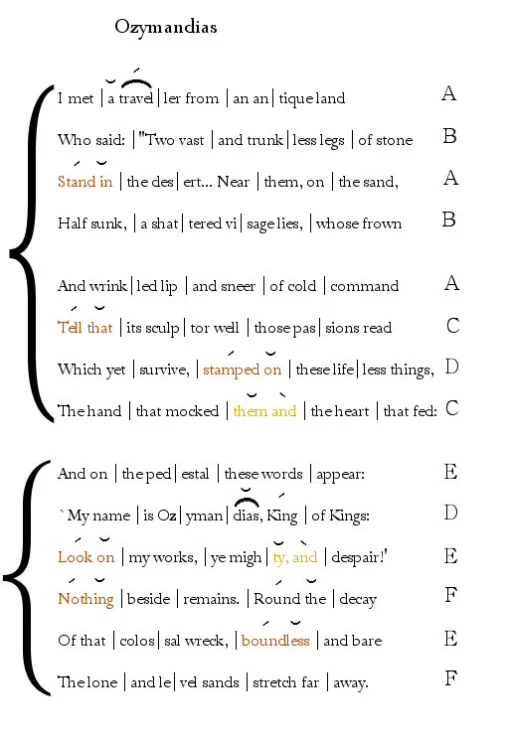

The Sonnet and its Scansion

- Note! I notice that many internet versions of this poem (including the video below) have “To feel for ever its soft fall and swell,” instead of “To feel for ever its soft swell and fall“. This may be a viral mistake. One text was typed incorrectly and everyone else copied and pasted. On the other hand, I notice that a copy in The Oxford Book of Sonnets prints the former version. The version I use is from Jack Stillinger’s the Poems of John Keats, considered to be the most accurate textually. He states that his text is “from the extant holograph fair copy” [p. 327]. I put my money on Stillinger. However, there are metrical reasons why I consider Stillinger’s to be correct. More detail on that below.

The first thing to notice about the sonnet is that it’s a Shakespearean Sonnet. If you’re not sure what that entails then follow the link and you will find my post on Shakespearean, Petrarchan and Spenserian Sonnets. Also, if you’re not sure about scansion or how it’s done, take a look at my post on The Basics. Keats wrote Sonnets in a variety of forms. That he chose the Shakespearean Sonnet, I think, is telling. With all the other parallels, why not the structure of the sonnet?

The form allows Keats to gradually build the the sonnet toward the epigrammatic climax of the couplet:

Still, still to hear her tender-taken breath,

And so live ever–or else swoon to death.

The second thing to notice is the meter itself. The first line of the first quatrain is, perhaps, the most easily misread, like Shakespeare’s Sonnet 116 or Donne’s Death Be Not Proud. We live in an age when Meter has become a art for fringe poets. As a result, many, if not most, modern poets and readers misread metrical poetry for lack of experience and knowledge. Most modern readers would probably read the line as follows:

Bright star, would I were stedfast as thou art–

This makes a hash of the meter, effectively reading the line as though it were free verse. But Keats was writing in a strong metrical tradition. As I’ve said in other posts, if one can read a foot as Iambic, then one probably should. So instead of reading the line like this:

We should probably read it like this:

Or we should read the final foot as an outright spondee (as I originally scanned it):

Fortunately, unlike my fruitless search for a good reading of Donne’s sonnet, I found a top notch reading of the poem on Youtube. Here it is:

To my ears, he reads the last foot as a spondee. None of these alternate last feet are iambs, by the way. When I say that a foot should be read as an Iamb if it can be, I mean that a foot should be read with a strong stress on the second syllable (an Iamb or Spondee), rather than a falling stress (a trochee). The other reason for emphasizing art is that it’s meant to rhyme with apart. If one de-emphasizises art with a trochaic reading, then we end up with a false rhyme. Two nearly unpardonable sins would have been committed by the standards of the day. A trochaic final foot in an Iambic Pentameter pattern (unheard of) and an amateurish false rhyme. Keats was aiming for greatness. We can be fairly sure that he didn’t intend a trochaic final foot.

Bright star, would I were stedfast as thou art–

Not in lone splendour hung aloft the night

And watching, with eternal lids apart,

Like nature’s patient, sleepless Eremite…

Other than that, the first quatrain is fairly straightforward. An eremite is a hermit. So, what Keats is saying works on two levels. He wants to be steadfast (and by implication her as well), like the North Star (Bright Star), but not in lone splendor – not in lonely contemplation. Keats isn’t wishing for the hermit’s patient search for enlightenment. Nor, importantly, is he wishing for the hermit’s asceticism – his denial of passion and earthly attachment – in a word, sex.

The moving waters at their priestlike task

Of pure ablution round earth’s human shores,

Or gazing on the new soft-fallen mask

Of snow upon the mountains and the moors;

In the second quatrain Keats describes the star’s detachment, like the hermit’s, as one of unmoving observation and detachment. The star’s sleeplessness is beautiful and it’s contemplation holy – observing the water’s “priestlike task of pure ablution”. But such contemplation is, for Keats, an inhuman one. It’s no mistake that Keats refers to the shore’s as earth’s human shores – a place of impermanence, fault and failings in need of “pure ablution”. This the world the Keats inhabits. Up to this point, all of Keats’s imagery is observational. The only hint of something more is in the tactile “soft-fallen”. There is little sensual contact or life in these images; but the first two quatrains present a kind of still life – unchanging, holy, and permanent. That said, there’s the feeling that the “new soft-fallen mask/ Of snow upon the mountains” anticipates his lover’s breasts.

The Volta

The sonnet now turns to toward life and, ironically, impermanence. Notice the nice metrical effect of spondaic first foot, it’s emphasis on the word No. One can produce a similar effect in free verse, but the abrupt reversal of the meter, also signaling the Sonnet’s volta, is unmatchable.

No–yet still stedfast, still unchangeable,

Pillow’d upon my fair love’s ripening breast,

To feel for ever its soft swell and fall,

Awake for ever in a sweet unrest,

Notice how the imagery changes. We are suddenly in a world of motion, touch, and feeling. No, says Keats, he wants the permanence of the star but also earth’s human shores. He wants to be forever “pillow’d upon [his] fair love’s ripening breast”. The anthimeria of pillow, using a noun as verb, sensually implies the softness and warmth of Fanny Brawne’s breasts. The next line gives life and breath to his imagery: He wants to feel her breasts “soft swell and fall” forever “in a sweet unrest”. The sonnet’s meter adds to the effect – the spondaic soft swell follows nicely on the phyrric foot that precedes it, reproducing, it its way, the rise and fall of her breasts. (Also, it’s worth noting that metrically, it makes more sense to have soft swell be a spondaic foot, rather than (as with some versions of the poem) soft fall. The meter, in a sense, swells with the intake of Fanny’s breath. ) Anyway, on earth’s human shores, there is nothing that is unchangeable and immutable. And Keats knows it. The irony of Keats’ desire for the immutable in a mutable world must find resolution – and there is only one:

Still, still to hear her tender-taken breath,

And so live ever–or else swoon to death.

If he could, he would live ever so, but Keats knows the other resolution, the only resolution, must be death.  Immutability, permanence and the unchangeable can only be found in death.

Immutability, permanence and the unchangeable can only be found in death.

But what a way to die…

And this brings us to the erotic subtext of the poem. As I wrote earlier, the idea of orgasm, which the French nicely call the little death or la petite mort, is an ancient conceit (the photo at right, by the way, is called La petite mort, clicking on the image will take you to Kirilloff’s gallery). If we read Keats’ final words as a wry reference to the surrender of orgasm, then there’s a mischievous and wry smile in Keats’ final words. After all, how do readers interpret “swoon“? Webster’s tells us that to swoon is “to enter a state of hysterical rapture or ecstasy…” Hmmm…. It’s hard to know whether Keats had this in mind. He never wrote overtly sexual poetry, but there is frequently a strong erotic undercurrent to much of his poetry. He was, after all, a sensualist. (Many of the poets who came after him accused him of being an “unmanly” poet – of being too sensuous and effeminate. Keats’ eroticism runs more along the lines of what is considered a feminine sensuality of touch and feeling.)

Such overt suggestiveness might be a little out of character for Keats but, if it was intended, I think it adds a nice denouement to the sonnet. After all, what is a lust and passion but a “sweet unrest”? And what is the only release from that “sweet unrest” but a swoon to death? But in this “death”, life is renewed. Life is engendered, remade and made immutable through the lovers’ swoon or surrender to “death”. Keat’s paradoxical desire for the immutable is resolved. The pleasure of the mutable but sweet unrest of his lovers rising and falling breasts, is only mitigated by the even more pleasurable, eternizing and transcendent pleasure of “death’s swoon”.

Which does Keats prefer? The immutable pleasure implied by the analogy of the changeless star, or the swoon of death? Keats, perhaps, is ready to find pleasure in both. The sonnet is profoundly romantic but, in keeping with Keats’ character, wryly pragmatic.

But this interpretation is conjectural. To Amy Lowell, the final lines are characterized as ending in a “forlorn, majestic peace” and I think this is how the majority of readers read the poem. I, personally, can’t help but think that there was more to Keats’ desire than Romantic obsession. The sheer, physical sexuality of resting his cheek on his lover’s breasts is more than just Romantic boiler plate.

The First Version

And here’s something won’t see very often on the web – considered to be Keats’ first version of the Sonnet.

Bright star, would I were stedfast as thou art–

Not in lone splendour hung amid the night

And watching, with eternal lids apart,

Like nature’s devout, sleepless Eremite,

The morning waters at their priestlike task

Of pure ablution round earth’s human shores,

Or gazing on the new soft-fallen masque

Of snow upon the mountains and the moors–

No–yet still stedfast, still unchangeable,

Cheek-pillow’d on my Love’s white ripening breast,

Touch for ever, its warm sink and swell,

Awake for ever in a sweet unrest,

To hear, to feel her tender-taken breath,

Half passionless, and so swoon on to death.

To students of poetry, what is worth noting is how few changes made a moving but flawed sonnet into a work of genius. As I’ve said before , it’s not the content of poetry that makes it great, but the style – the language. The first version, in terms of content, is ostensibly the same as the second version.

- Changing amid to aloft gives the feeling of a star that is apart from the others, aloft, rather than amid.

- The adjective devout is simply descriptive – having little connotative power. But the adjective patience is attributive and gives the description the force of personality. It also plays against Keats’ sweet unrest, later in the sonnet. Patience, Keats tells us, is not an attribute he wants to mimic, only its steadfastness and unchangeableness.

- The change of morning to moving, again changes a simply descriptive adjective to an attributive adjective. Moving gives the waters motion and a kind of intent. It also avoids the conflict of the star having been hung aloft the night, but watching the morning waters.

- Keats’ initial choice of masque is curious and may be a misprint. A masque is a short, usually celebratory, one act play.

- “Cheek-pillow’d on my Love’s white ripening breast,” gives us more information than we need. We can already guess that it’s his cheek on her breasts because he uses the anthemeria pillow’d. What else do we put on our pillows but our cheeks? Her white breast is unnecessary. All but a handful of 19th Century English women had white breasts. Keats was just trying to fill out the meter with the adjective white. “Pillow’d upon my fair love’s ripening breast,” dispenses with both of the former redundancies. The word fair is there solely for the sake of the meter, but doesn’t feel as extraneous or contrived as white. It also allows the emphasis to turn to ripening, which is a beautifully erotic description of a young woman’s breast.

- “Touch for ever, its warm sink and swell,” The verb touch lacks the rich connotation of feel. After all, we might forensically touch a hot kettle, to find out if it’s too hot; but we wouldn’t feel it. Feeling things is a tactile, sensual act when we want to explore an object. Warm sink and swell is replaced by soft swell and fall. Once again, the adjective warm lacks the connotative sensation of soft. To know that something is warm, we don’t necessarily need to touch or feel it. But to know something is soft implies a more tactile and sensual exploration. The verb sink is a less neutral expression than fall. Boats sink. Rocks sink. Drowning swimmers sink. Most importantly, when objects sink, they tend not to rise again. Fall is a more neutral, less loaded description. It also rhymes better with unchangea(ble). Keats may have been uneasy with the rhyme between (ble) and swell.

- To hear, to feel is replaced by Still, still to hear. The latter phrase gives the final couplet a more dramatic, less literary feel. We can hear the wistfulness and expectation of an actual speaker in the disrupted meter – the epizeuxis of Still, still…

- The final line is the most dramatic alteration: “Half passionless, and so swoon on to death.” Half passionless undercuts the eroticism of the poem. Who is half-passionless? Keats? Brawne? What does that mean? The closing line appears to give the sonnet’s ending a more despondent tone, conflicting with the idea of a sweet unrest. Keats probably meant to imply that his ardor was both like the star’s, detached, and like attachment of a lover. But I suspect he sensed the contradiction in the description. It undercuts what had, until then, been a profoundly passionate poem. It also undercuts the erotic suggestiveness of a swooning death.

And here is the companion Sonnet Fanny Brawne wrote into her copy of Dante:

As Hermes once took to his feathers light,

When lulled Argus, baffled, swooned and slept,

So on a Delphic reed, my idle spright

So played, so charmed, so conquered, so bereft

The dragon-world of all its hundred eyes;

And seeing it asleep, so fled away,

Not to pure Ida with its snow-cold skies,

Nor unto Tempe, where Jove grieved a day;

But to that second circle of sad Hell,

Where in the gust, the whirlwind, and the flaw

Of rain and hail-stones, lovers need not tell

Their sorrows. Pale were the sweet lips I saw,

Pale were the lips I kissed, and fair the form

I floated with, about that melancholy storm.

If this post was enjoyable or a help to you, please let me know! If you have questions, comments or suggestions. Comment. In the meantime, write (G)reatly!

Bright Star by Jane Campion

Don’t know much about the movie. But as with all movies like these, it may be based on a true story, but it remains a work of fiction. I can’t wait to see it.

![Paradise Lost Book 8 [Extract] Paradise Lost Book 8 [Extract]](https://poemshape.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/04/paradise-lost-book-8.jpg?w=310&h=456)