- This reading is a paid commission and has brought me a little ways out of my funk. Commissions are open. That is, anyone is welcome to commission a reading of their favorite poem or even just a poem.

So, since I’m on a short time line, let’s get right to the poem, written by the late Canadian poet Irving Layton. You can read some of Layton’s biography at  Wikipedia. The poem itself can be found in the book Irving Layton: A Wild Peculiar Joy. The book can also be perused at Google Books. It’s from the latter site that I copied the poem, just to be sure I had it right. And here it is:

Wikipedia. The poem itself can be found in the book Irving Layton: A Wild Peculiar Joy. The book can also be perused at Google Books. It’s from the latter site that I copied the poem, just to be sure I had it right. And here it is:

I have seen respectable

death

served up like bread and wine

in stores and offices,

in club and hostel,

and from the streetcorner

church

that faces

two ways

I have seen death

served up

like ice.

Against this death,

slow, certain:

the body,

this burly sun,

the exhalations

of your breath,

your cheeks

rose and lovely,

and the secret

life

of the imagination

scheming freedom

from labour

and stone.

When possible, I like to know a poet’s biography. Within limits, it can be helpful trying to get behind the poets  words. In the case of Irving, what caught my attention was his humanism, his interest in politics and social theory, his reading in Marx and especially Nietzsche. He joined the Young People’s Socialist League when young. Marx considered religion to be the opiate of the masses and Nietzsche famously wrote that the last Christian died on the cross. Nietzsche wrote On the Genealogy of Morals, a book that all but eviscerates the pretense of morality in Christianity. I certainly don’t know the degree to which Layton adopted the world views of these authors, but his reputation as a humanist argues that something brushed off.

words. In the case of Irving, what caught my attention was his humanism, his interest in politics and social theory, his reading in Marx and especially Nietzsche. He joined the Young People’s Socialist League when young. Marx considered religion to be the opiate of the masses and Nietzsche famously wrote that the last Christian died on the cross. Nietzsche wrote On the Genealogy of Morals, a book that all but eviscerates the pretense of morality in Christianity. I certainly don’t know the degree to which Layton adopted the world views of these authors, but his reputation as a humanist argues that something brushed off.

I have seen respectable

death

Why respectable? It’s a strange way to refer to death. Respectable can mean “esteemed, deserving regard; of good repute”; but there’s also a more  socially loaded sense of the word. For instance, when one refers to a respectable woman, there’s also the unstated but implied condemnation of all the women who are not respectable. In this sense, a respectable death might be “characterized by socially or conventionally acceptable morals”. In other words, respectable death can be understood as referring to a certain kind of socially and conventionally accepted conception of death.

socially loaded sense of the word. For instance, when one refers to a respectable woman, there’s also the unstated but implied condemnation of all the women who are not respectable. In this sense, a respectable death might be “characterized by socially or conventionally acceptable morals”. In other words, respectable death can be understood as referring to a certain kind of socially and conventionally accepted conception of death.

served up like bread and wine

in stores and offices,

in club and hostel,

When is death served up like bread and wine? At the Eucharist.

“The sacrament of the Lord’s Supper; the solemn act of ceremony of commemorating the death of Christ, in the use of bread and wine, as the appointed emblems; the communion.” The Collaborative International Dictionary of English v.0.48

In most denominations, the bread is understood as being (or representing) the flesh of Christ and the wine is his blood.

“For I received from the Lord what I also delivered to you, that the Lord Jesus on the night when he was betrayed took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it, and said, “This is my body which is for you. Do this in remembrance of me”. (1 Corinthians 11:23-24)”

But Layton first locates us in stores, offices, the club and the hostel. Since the Eucharist isn’t something that’s celebrated outside of church, the reader is forced to read “bread and wine” figuratively (and also with a sense of irony).

Note: Understanding “bread and wine” in its figurative sense means interpreting the phrase as applying to any activity in which our preoccupation is with death rather than life. In other words, when we sit in a club and colorlessly exchange our zest for life for a socially condoned fear of death, we embody the”respectable death” of the indoctrinated.

Catholics refer to the Eucharist as a sacrament (through which Christ bestows salvation), but protestants prefer the term ordinance, viewing the Eucharist “not as a specific channel of divine grace but as an expression of faith and of obedience to Christ”. If understood in this latter sense, then partaking in the poem’s “bread and wine” may more broadly be understood as professing obedience to death’s preeminence over life.

This is ‘respectable death’ or a proper and societally approved conception of death.

Respectable death, like the respectable woman, refutes anything like a celebration of the flesh — its pleasures, joys, inherent flaws and decadent habituations. Supremacy is given to mortality and God’s judgment. We are, by the “bread and wine” of tradition and fear, made respectable and conventionally moral. Even in the mercantile stores, the industrious offices, the raucous club and the youthful hostels, death is given preeminence.

and from the streetcorner

church

After figuratively secularizing “bread and wine”, the poem denies the sacred pretense of the Eucharist. That is, the “bread and wine” of the Eucharist is no different, in effect, than the moral indoctrination served up in stores and offices. This sacred and secular indoctrination are, in intent, one and the same.

that faces

two ways

In ancient Roman religion, Janus was the god of beginnings and transitions, gates, doors, passages, endings and time. He was the god of two faces who faced two ways.  These two lines can be interpreted as comparing the Church to Janus. The chuch, like Janus, looks to the future and the past. Here’s how Wikipedia puts it as of writing this:

These two lines can be interpreted as comparing the Church to Janus. The chuch, like Janus, looks to the future and the past. Here’s how Wikipedia puts it as of writing this:

“Janus frequently symbolized change and transitions such as the progress of future to past, from one condition to another, from one vision to another, and young people’s growth to adulthood. He represented time, because he could see into the past with one face and into the future with the other.Hence, Janus was worshipped at the beginnings of the harvest and planting times, as well as at marriages, deaths and other beginnings. He represented the middle ground between barbarism and civilization, rural and urban space, youth and adulthood. Having jurisdiction over beginnings Janus had an intrinsic association with omens and auspices.”

The one thing, perhaps, that Janus does not perceive is the now. Now is where life occurs. Now concerns itself with neither change nor transition. It is, in a sense, changeless. Now simply is. Living in the now, however, can easily be perceived as a kind of anarchic decadence. A life that cares nothing for the future or the past is going to subvert tradition (tradition being based on a respect for the past) and undermine morals (the latter being based on the fear of future judgment). It’s in this sense, perhaps, that the Church is being compared to Janus. The Church looks both ways too, insisting on reverence for the past while instilling a fear of the future; but cannot and will not perceive or celebrate the now that is life. The church, in this sense, intrinsically distrusts the now.

Note: There are three lines in the poem composed of a single word: death/church/life. (The beauty of free verse is that it allows for this kind of typographical presentation.) Like Janus, the church is typographically centered between death, at the beginning of the poem, and life at the close of the poem. It’s possible and tempting, therefore, to interpret this as meaning that the church is the essential nexus in the transition between birth, life and death. However, this runs somewhat counter, I think, to the theme of the poem. A more likely interpretation, perhaps, is that Layton is emphasizing a choice presented by the two stanzas: death and church in the first stanza verses life in the second. Church can be understood as an institutional symbol of the lifeless preoccupation with death and conventional morality.

By the end of this first stanza, it’s easy to read an ironic and skeptical sneer in Layton’s use of the word respectable.

I have seen death

served up

like ice.

Ice is nothing if not joyless, humorless and lifeless. Additionally, there is also the implication of an icy and coldy calculating intent.

So, summing up the first stanza, one interpretation might be as follows:

“I have seen “respectable death” (a confining and conventional fear of death) served up like the “bread and wine” of the Eucharist (like a kind of societally approved and deadening indoctrination) in stores, clubs, offices, hostels and the church. I have seen death (the fear of death) served up like ice (coldly and calculatedly).“

The next stanza will refute this preoccupation with the past, the future, death and respectability. It’s possible, if not easy, to read the first stanza as a Nietzschean indictment of the church, but I think that Layton’s indictment is more broad based than that. He is inditing a whole way of thought typified in the indoctrinating and ritualized symbolism of “bread and wine”. Instead, he offers a kind of Dionysian alternative, a full-blooded — not wine — and full fleshed — not bread — vision.

Against this death,

slow, certain:

the body,

Instead of bread, he gives you the body. Live in the now. Live in the body. Celebrate the pleasures and joys of the body: sleep, sex, drink, debauchery and sheer physical exuberance. Celebrate the body’s nowness,

Instead of bread, he gives you the body. Live in the now. Live in the body. Celebrate the pleasures and joys of the body: sleep, sex, drink, debauchery and sheer physical exuberance. Celebrate the body’s nowness,

this burly sun,

the exhalations

of your breath,

your cheeks

rose and lovely,

Turn your mind away from numbing, souless burdens of the past and future. The stores, offices, clubs and hostels and church are all, even at their best, closed, limited and confining. Go into the burly sun. There is nothing more present and in the now than the awareness of ones exhalations — ones breath. To breathe is to live and the reference to breathe could be an allusion to ‘Atman’. In Hindu philosophy, “the word `Atman` is derived from ‘an’ which means ‘to breathe’, which is ‘the breath of life’. The meaning of the word changed with time and it covered life, soul, self or essential being of the individual.” To be aware of ones breath is to acknowledge the preeminence of life. There is also surely a deliberate pun on Rosé. The “rose” in our cheeks is the true wine — the living blood that courses through our veins.

Instead of bread, partake of the body. Instead of wine, partake of the blood in the cheek. In short, instead of the respectable, cold confinement of idea and symbolism, choose (against this death) the life of the body.

and the secret

life

of the imagination

Think freely. Live the secret life of your imagination. Why is it secret? The implication is that it’s because it’s not respectable. The secret life of your imagination will not be “characterized by socially or conventionally acceptable morals”. Live it anyway! — says the poem. (Knowing that Layton read Nietzsche, one can’t help but suspect Nietzsche’s presence.)

- The drawing of the sun, above center, is by Laurie Gibson and can be purchased here.

scheming freedom

from labour

and stone.

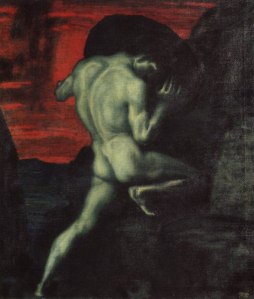

The imagination must scheme because the imagination, by definition, will reject the imposition of conventional order and morality. The imagination seeks to create the new and the unconventional. The amoral and unconventional spirit will reject the conventional morality and  order implied by “labour and stone”. The stone can be understood as the inflexible and implacable order of the church. The mention of labour, in combination with the stone, is possibly an allusion to the myth of Sysiphus — a rich and appropriate allusion. In other words, the poem is comparing the lifeless preoccupation of the respectable death to the labour of Sysiphus, who will always roll the same stone to the top of the mountain, but will never succeed in keeping it there.

order implied by “labour and stone”. The stone can be understood as the inflexible and implacable order of the church. The mention of labour, in combination with the stone, is possibly an allusion to the myth of Sysiphus — a rich and appropriate allusion. In other words, the poem is comparing the lifeless preoccupation of the respectable death to the labour of Sysiphus, who will always roll the same stone to the top of the mountain, but will never succeed in keeping it there.

The stone will always roll back to the bottom and Sysiphus will push it, again and again, back to the top. The task is insoluble. Likewise, the Janus-like preoccupation with a respectable death is insoluble. The mystery of death will never be solved. The only solution is to free oneself from any Sisyphean preoccupation with death and live freely in the now, in the rosy and lovely cheek, the exhaled breath, the burly sun, and the body. Leave behind the dessicated symbolism of bread and wine. Free your imagination.

The poem may be understood as contrasting (and preferring) the amoral, anarchic and joyful now of the body against the slow and certain death of a soulless conventionality confined by tradition and fear — what he calls “this death” and a “respectable death”.

August 10 2013 • up in Vermont