she brings

to me the frank contagion of

an afternoon; the moon’s delirium when

the sun, too soon, goes down. I pick the panicles

of grass that dart her dress—I love

her dress. I love it the color of her hips

and love the green odor of the summer’s cuttings

at her lips; and I forget myself,

I—the smelting of ore into the bone

and tissue of an hour—am made, for an hour,

more than what I am.

she arrives

through slow intersections where

the riders come and go; she among them, opening

her umbrella into snow. she arrives.

I take her raincoat and umbrella

and where we sit before the window, the windows

outside our own show buildings from

the inside out; and here and there

the men and women like ourselves who gather

as we gather, who take wine

wineglass, cutting board and bread

before the window-lit climes of the city.

the streets thrum below us with their ebb

and flow. let’s drink to the waves, I say,

we can’t see but feel incessantly

against the window’s glass; the tide

subsiding beneath the mass of steel and concrete

façades.

don’t ask what savagery

or tenderness, what thousand lives

have brought her life and mine together. the sands

of Troy are clotted by the blood

of men, killing and killed for Helen’s beauty—

and love.

when she’s mine again

and the great ships set sail and the fire

and feast are done, the snow’s ashes descend

on the cars parked and departing. what ruins we leave

we never leave behind.

the girl,

the girl with the many-colored braids

replies: love leaves no ruins. she, barefooted,

who dances in the scarab’s eye with enameled hair

and lips. she leaps over the leaping seas.

love leaves no monuments, she says, no cold

command or shattered torsos sinking, sinking

into the desert sands.

a cracked tin pail

locked in ice beneath the barn light catches

the snow and roundabout the bottom where

the tin is welded, rust has rusted through;

and were there anyone to pick it up

the bottom, where the raindrops drum, would fall

into the mud.

the girl who dances, dances

in rusty pails and to the singing rails

of streetcars. some nights the river walks

among the signs and storefronts, and smears

the watery roads with lampposts; the evergreens

with its twisting gray ribbons. some nights walking

along the river bank, the waters move

in leaden contemplation, darkly indifferent

to what reflects.

the girl who dances, dances

among the shock of willows and her hair

is rapturous as the water-witch. love leaves

no ruins, she says. love builds no edifice

of glass or stone but beats the drum of flesh

and bone.

let go the finch’s cry, the cry

of root and mud; the stench of earthen growth

out of the ruinous sludge, and from the soil

the berries of the spindle tree, but

the berries—colored like the girl’s lips—

are poisonous to taste or kiss. do you see

the purple shadows drip and pool beneath

the yellow birch?

She’s dancing in an orange

and yellow skirt. she won’t answer where

she goes. The rain has turned to snow; the bus

pulls out into the afterglow of brakes

and headlights.

I’ve seen her out among

the cattails, dancing in a rusty pail,

but don’t believe me. I’ll lie for beauty,

I’ll burn the city to the ground; the sands

To sheets of glass. I’ll pull the towers down,

I’ll throw the pail into the trash—the rusted pail.

The snow has turned to ash.

the sun’s still not gone down

and out the bedroom window is the laundry,

the wind billows in the sail of sleeves

and lifted backs as though the clothes and bed sheets

pulled the world after them into

the distant waters—the world’s dark waters

that edge a summer’s field with starlight. we are

ourselves our passion’s ruins. I say

To her, the downspout buckled, maybe

tomorrow I’ll replace it. I’ve waited

so long to mow that now the tall grass flounders under

the heady weight of seed.

I stood outside the store,

a scarecrow looking in.

I saw her standing by the door

reading novels in Berlin;

but this is how it’s always been.

I can’t remember why

her lipstick tastes like tin.

she liked to sing to Zoltan Kodály

and wished I played the violin;

but this is how it’s always been.

I walked the Spree with her

as the city inked her skin;

I should remember where we were

the day we parted over gin;

but this is how it’s always been.

as I

was saying

before the sparks

of a streetcar interrupted us—

a streetcar scudding through the cobblestones

beneath electric sails;

as I

was saying: let us be naked side

by side. there’s nothing better or as truthful.

let us lie together and let us lie. there’s nothing otherwise

to make sense of.

don’t try.

don’t try.

Patrick Gillespie | March 17th 2021

Quintet in C

Category Archives: Free Verse

Ode to Kim Addonizio

someday

you’ll sit across from me saying

similes explain the human

condition—we can never be ourselves

but only like ourselves (though some of us

ascend to metaphor).

at first I won’t

know what the hell you’re talking about

(and maybe never). what does it even mean

to be like ourselves if we’re not already

ourselves? but I’ll agree because

even if the meaning isn’t self-

evident, profundity is implied; and you

will likely remind me of girlfriends

I used to drive cross-country with (their

bare legs lifted, their feet out the passenger side

window V’d like the winged heels of a Greek

Goddess, ankles crossed on the rear view mirror)—

when all I could think about

was the intoxication of a girl’s bare feet

in an 80 mph air stream; and you might say:

that’s the way it is to be a barefooted

girl—always that 80 mph wind licking your feet

until the tank runs out of gas

until the sun runs down the sky, until she finds

herself landed barefoot on the sun-cracked

asphalt of a seedy, run down

motel where the parking shines with glass

ground to glitter after God knows how many bottles

and demands.

but afterward in bed,

I know, it won’t be me she remembers

but the 80 mph hour wind like fingers

at her ankles that, if they could have, would

have parted her thighs and you

have no idea or, knowing you, you do,

what an 80 mph wind can do to the imagination

(or a hippy sundress); but anyway, we didn’t even

get that far because she’d say something like,

‘we can only ever be like ourselves

never ourselves,’ or she’d say,

‘all men ever want to do is fuck me’

and Christ, I’d want to say, is that so much

to ask? and before the end of the road trip she’d

be hitchhiking to LA and

I’d be broken down in Wichita.

maybe you’re wishing you were in LA too?

I have that effect on chicks like you.

and by the way I expect

you’re the type who reads the rhymes

in a toilet stall. goddamn those people

know how to write—artists and poets all.

and know damned well who their audience is

and where to find them.

I wouldn’t be surprised

if you came back from that temple

of runes and oghams reciting

what omen was given you to give the masses:

women drinking booze

talk of dicks and new tattoos

and that has me asking if there shouldn’t be

a comparative lit course in men’s and women’s

toilet stalls; and anyway what happened

to you and rhyming? is nobody singing you the blues?

do you really think if Keats had to choose

between you and Fanny Brawne,

you’d stand a chance if she recited lines

about crumbling cathedrals and dandelions?—

in corseted iambic pentameter

with a bouquet of rhymes? you poor

deluded poet. have you even read your own poetry?—

lately?

there’s more anatomy

than tits and ass that sag, though maybe yours

were archetypal? i don’t know

but honestly, does the world really need

more self-pitying poets eulogizing the loss

of their fearful symmetry?

we’ll soon enough all fit inside a Grecian urn—

but I feel your pain.

did I tell you about the time I met

Hayden Carruth in Bennington, Vermont?

there may have been me, his publisher,

students and admirers, but there was mostly

the red-haired woman in the sleeve-wrap leopard print

top and black leather mini-skirt

and I can tell you there was no talking poetry

that night or at that table with Hayden Carruth.

Carruth is your poet. Keats

never knew how to treat women, but Hayden?

I tell you, go for the man with the yellow McCulloch

chainsaw.

but who hasn’t woken

to some new piece of poetry wondering

what in the hell happened

the night before? who said what and what

was spoken and never mind the hangover—what’s

the fucking title? I’ve been there—

a fifth of rum, midnight, some piece grinding

moves on the dance floor, moves

I’ve never seen before until, the next morning,

I’m wondering what-the-hell future I ever saw in it.

must have been the drink because I can’t

begin to explain whatever goddamn

Picasso of indiscretion I woke to—words tossed

like underwear across the exaltation

of the page. spontaneity. sure. call it that. the kind

you used to find at a 90s rage;

but as I was saying: isn’t anybody, these days,

singing you the blues?

women drinking booze

talk of dicks and new tattoos

stuck in my head now

for Christ’s sake, but haven’t any

of those poets promised, at midnight,

to walk you sly along the railroad track?—

just smooth as Scratch himself?

‘don’t you know,

‘sweet girl,’ he’d say, ‘the kinds of rhymes your hips

could make with mine?’

take me down your boulevard

of saints and swindles, where the old men leer

and the young men sing beatus vir;

where the women preen with looks as flammable

as gasoline. let’s you and me find out

the lanes and alleyways that rub against

the skin, where neon advertises sin

and preachers lick the air sweet with the carnal

and serpentine locution of the streets;

we’ll find a sidewalk curb or sway backed porch steps—

we’ll sit among the bottle caps and cups

the foil, paper wrappers, and cigarette butts

and talk about the raff we leave behind:

the drafts and stanzas; maybe here and there

a poetry worth the reading? but why guess?

go a few stone steps into the cellar

and there the mystic Madam Coriander,

who owns the laundromat around the corner,

will tell us how the roots of the raspberries finger

the sockets of a skull—

Mary, where the thorns are many,

where the autumn’s black leaves eddy

do you hear the children skipping

while your bloodless bones are slipping?

Mary, Mary, dead and buried,

buried beneath the red raspberries.

one for the money,

two to elope,

three for the noose

in the jump rope’s rope.

four for the crime

beware of four!

four’s for the rhyme:

Mary’s no more.

Mary, Mary, in the brambles

where the barren winter ambles

do you hear the children’s laughter

singing of the ever after?

Mary, Mary, dead and buried,

buried beneath the red raspberries.

—the thorns, the brambles,

the twisted vine are growing from my skull,

and children pick the berries—I see it all.

I hear them mocking the divine, their laughter,

and Madam Coriander asking if

I understand. do you? my mouth is filled

with sand and weeds are sprouting from my eyes.

I can’t decide. but do you know the spikes

of bulrush where the river dimly swims?

down by the salt-fingered pilings? I’ve been meaning

to describe the way the yellow lights

oil the river’s slippery back, the wharf,

the detritus of the clouds before they’re swept

at midnight out to sea. there’s a place

the moon goes up mechanically. behind it

the turning plate of stars goes round and round

the blinking lights. there’s not a night I’d trade

for this but I digress. the filigree

of roots, the brazen nettles, the skull beneath

the winterberry—was it winterberry?

I’m guessing you would answer: whiskey. whiskey

works just as well. you could almost mistake

the sky— let’s put it this way: let’s say

we stuck our feet out of the world’s side window,

the ocean rolling underneath. we’ll tell them

we crossed our ankles on the far horizon

and dipped our toes into the moon, we stirred up

comets and let the streaming Milky Way

wash clean our feet. (don’t ask me who the hell

is driving.)

but we’ve been here before,

barefooted in the parking lot. don’t ask

the exit number. if I’m first arriving,

I’ll have the front desk bring your room a bottle

of Vanni Fucci (if that isn’t wine

it should be) vintage 1954—

I wonder if you like my metaphor?

but then I’m thinking back again to driving

with my girlfriend’s heels on the rear-view mirror, and

she asks me—’don’t you understand?

we’re never ourselves but only

like ourselves: the skull, the briars, the raspberries,

winterberries or whatever—

what Madam Coriander meant

was: in the end—but you should change the poem

to winterberries. you never

eat a winterberry raw—they’re poisonous.’

but raspberries bleed, I say.

and by this I mean: if I hear you caterwauling

at the trash bins in the middle of the night, I’ll always

put out a saucer-full of gin

for you.

Ode to Kim Addonizio

writ by me

January 3rd 2023

- I wrote this over the last couple days reading Now We’re Getting Somewhere. Small references to What Is This Thing Called Love also appear. There’s a footnote to my jump rope poem I almost added:

1. this might be a little darker

than your average Dorothy Parker.

the annotated “Against this Death”

- This reading is a paid commission and has brought me a little ways out of my funk. Commissions are open. That is, anyone is welcome to commission a reading of their favorite poem or even just a poem.

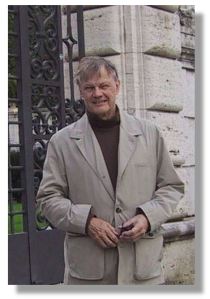

So, since I’m on a short time line, let’s get right to the poem, written by the late Canadian poet Irving Layton. You can read some of Layton’s biography at  Wikipedia. The poem itself can be found in the book Irving Layton: A Wild Peculiar Joy. The book can also be perused at Google Books. It’s from the latter site that I copied the poem, just to be sure I had it right. And here it is:

Wikipedia. The poem itself can be found in the book Irving Layton: A Wild Peculiar Joy. The book can also be perused at Google Books. It’s from the latter site that I copied the poem, just to be sure I had it right. And here it is:

I have seen respectable

death

served up like bread and wine

in stores and offices,

in club and hostel,

and from the streetcorner

church

that faces

two ways

I have seen death

served up

like ice.

Against this death,

slow, certain:

the body,

this burly sun,

the exhalations

of your breath,

your cheeks

rose and lovely,

and the secret

life

of the imagination

scheming freedom

from labour

and stone.

When possible, I like to know a poet’s biography. Within limits, it can be helpful trying to get behind the poets  words. In the case of Irving, what caught my attention was his humanism, his interest in politics and social theory, his reading in Marx and especially Nietzsche. He joined the Young People’s Socialist League when young. Marx considered religion to be the opiate of the masses and Nietzsche famously wrote that the last Christian died on the cross. Nietzsche wrote On the Genealogy of Morals, a book that all but eviscerates the pretense of morality in Christianity. I certainly don’t know the degree to which Layton adopted the world views of these authors, but his reputation as a humanist argues that something brushed off.

words. In the case of Irving, what caught my attention was his humanism, his interest in politics and social theory, his reading in Marx and especially Nietzsche. He joined the Young People’s Socialist League when young. Marx considered religion to be the opiate of the masses and Nietzsche famously wrote that the last Christian died on the cross. Nietzsche wrote On the Genealogy of Morals, a book that all but eviscerates the pretense of morality in Christianity. I certainly don’t know the degree to which Layton adopted the world views of these authors, but his reputation as a humanist argues that something brushed off.

I have seen respectable

death

Why respectable? It’s a strange way to refer to death. Respectable can mean “esteemed, deserving regard; of good repute”; but there’s also a more  socially loaded sense of the word. For instance, when one refers to a respectable woman, there’s also the unstated but implied condemnation of all the women who are not respectable. In this sense, a respectable death might be “characterized by socially or conventionally acceptable morals”. In other words, respectable death can be understood as referring to a certain kind of socially and conventionally accepted conception of death.

socially loaded sense of the word. For instance, when one refers to a respectable woman, there’s also the unstated but implied condemnation of all the women who are not respectable. In this sense, a respectable death might be “characterized by socially or conventionally acceptable morals”. In other words, respectable death can be understood as referring to a certain kind of socially and conventionally accepted conception of death.

served up like bread and wine

in stores and offices,

in club and hostel,

When is death served up like bread and wine? At the Eucharist.

“The sacrament of the Lord’s Supper; the solemn act of ceremony of commemorating the death of Christ, in the use of bread and wine, as the appointed emblems; the communion.” The Collaborative International Dictionary of English v.0.48

In most denominations, the bread is understood as being (or representing) the flesh of Christ and the wine is his blood.

“For I received from the Lord what I also delivered to you, that the Lord Jesus on the night when he was betrayed took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it, and said, “This is my body which is for you. Do this in remembrance of me”. (1 Corinthians 11:23-24)”

But Layton first locates us in stores, offices, the club and the hostel. Since the Eucharist isn’t something that’s celebrated outside of church, the reader is forced to read “bread and wine” figuratively (and also with a sense of irony).

Note: Understanding “bread and wine” in its figurative sense means interpreting the phrase as applying to any activity in which our preoccupation is with death rather than life. In other words, when we sit in a club and colorlessly exchange our zest for life for a socially condoned fear of death, we embody the”respectable death” of the indoctrinated.

Catholics refer to the Eucharist as a sacrament (through which Christ bestows salvation), but protestants prefer the term ordinance, viewing the Eucharist “not as a specific channel of divine grace but as an expression of faith and of obedience to Christ”. If understood in this latter sense, then partaking in the poem’s “bread and wine” may more broadly be understood as professing obedience to death’s preeminence over life.

This is ‘respectable death’ or a proper and societally approved conception of death.

Respectable death, like the respectable woman, refutes anything like a celebration of the flesh — its pleasures, joys, inherent flaws and decadent habituations. Supremacy is given to mortality and God’s judgment. We are, by the “bread and wine” of tradition and fear, made respectable and conventionally moral. Even in the mercantile stores, the industrious offices, the raucous club and the youthful hostels, death is given preeminence.

and from the streetcorner

church

After figuratively secularizing “bread and wine”, the poem denies the sacred pretense of the Eucharist. That is, the “bread and wine” of the Eucharist is no different, in effect, than the moral indoctrination served up in stores and offices. This sacred and secular indoctrination are, in intent, one and the same.

that faces

two ways

In ancient Roman religion, Janus was the god of beginnings and transitions, gates, doors, passages, endings and time. He was the god of two faces who faced two ways.  These two lines can be interpreted as comparing the Church to Janus. The chuch, like Janus, looks to the future and the past. Here’s how Wikipedia puts it as of writing this:

These two lines can be interpreted as comparing the Church to Janus. The chuch, like Janus, looks to the future and the past. Here’s how Wikipedia puts it as of writing this:

“Janus frequently symbolized change and transitions such as the progress of future to past, from one condition to another, from one vision to another, and young people’s growth to adulthood. He represented time, because he could see into the past with one face and into the future with the other.Hence, Janus was worshipped at the beginnings of the harvest and planting times, as well as at marriages, deaths and other beginnings. He represented the middle ground between barbarism and civilization, rural and urban space, youth and adulthood. Having jurisdiction over beginnings Janus had an intrinsic association with omens and auspices.”

The one thing, perhaps, that Janus does not perceive is the now. Now is where life occurs. Now concerns itself with neither change nor transition. It is, in a sense, changeless. Now simply is. Living in the now, however, can easily be perceived as a kind of anarchic decadence. A life that cares nothing for the future or the past is going to subvert tradition (tradition being based on a respect for the past) and undermine morals (the latter being based on the fear of future judgment). It’s in this sense, perhaps, that the Church is being compared to Janus. The Church looks both ways too, insisting on reverence for the past while instilling a fear of the future; but cannot and will not perceive or celebrate the now that is life. The church, in this sense, intrinsically distrusts the now.

Note: There are three lines in the poem composed of a single word: death/church/life. (The beauty of free verse is that it allows for this kind of typographical presentation.) Like Janus, the church is typographically centered between death, at the beginning of the poem, and life at the close of the poem. It’s possible and tempting, therefore, to interpret this as meaning that the church is the essential nexus in the transition between birth, life and death. However, this runs somewhat counter, I think, to the theme of the poem. A more likely interpretation, perhaps, is that Layton is emphasizing a choice presented by the two stanzas: death and church in the first stanza verses life in the second. Church can be understood as an institutional symbol of the lifeless preoccupation with death and conventional morality.

By the end of this first stanza, it’s easy to read an ironic and skeptical sneer in Layton’s use of the word respectable.

I have seen death

served up

like ice.

Ice is nothing if not joyless, humorless and lifeless. Additionally, there is also the implication of an icy and coldy calculating intent.

So, summing up the first stanza, one interpretation might be as follows:

“I have seen “respectable death” (a confining and conventional fear of death) served up like the “bread and wine” of the Eucharist (like a kind of societally approved and deadening indoctrination) in stores, clubs, offices, hostels and the church. I have seen death (the fear of death) served up like ice (coldly and calculatedly).“

The next stanza will refute this preoccupation with the past, the future, death and respectability. It’s possible, if not easy, to read the first stanza as a Nietzschean indictment of the church, but I think that Layton’s indictment is more broad based than that. He is inditing a whole way of thought typified in the indoctrinating and ritualized symbolism of “bread and wine”. Instead, he offers a kind of Dionysian alternative, a full-blooded — not wine — and full fleshed — not bread — vision.

Against this death,

slow, certain:

the body,

Instead of bread, he gives you the body. Live in the now. Live in the body. Celebrate the pleasures and joys of the body: sleep, sex, drink, debauchery and sheer physical exuberance. Celebrate the body’s nowness,

Instead of bread, he gives you the body. Live in the now. Live in the body. Celebrate the pleasures and joys of the body: sleep, sex, drink, debauchery and sheer physical exuberance. Celebrate the body’s nowness,

this burly sun,

the exhalations

of your breath,

your cheeks

rose and lovely,

Turn your mind away from numbing, souless burdens of the past and future. The stores, offices, clubs and hostels and church are all, even at their best, closed, limited and confining. Go into the burly sun. There is nothing more present and in the now than the awareness of ones exhalations — ones breath. To breathe is to live and the reference to breathe could be an allusion to ‘Atman’. In Hindu philosophy, “the word `Atman` is derived from ‘an’ which means ‘to breathe’, which is ‘the breath of life’. The meaning of the word changed with time and it covered life, soul, self or essential being of the individual.” To be aware of ones breath is to acknowledge the preeminence of life. There is also surely a deliberate pun on Rosé. The “rose” in our cheeks is the true wine — the living blood that courses through our veins.

Instead of bread, partake of the body. Instead of wine, partake of the blood in the cheek. In short, instead of the respectable, cold confinement of idea and symbolism, choose (against this death) the life of the body.

and the secret

life

of the imagination

Think freely. Live the secret life of your imagination. Why is it secret? The implication is that it’s because it’s not respectable. The secret life of your imagination will not be “characterized by socially or conventionally acceptable morals”. Live it anyway! — says the poem. (Knowing that Layton read Nietzsche, one can’t help but suspect Nietzsche’s presence.)

- The drawing of the sun, above center, is by Laurie Gibson and can be purchased here.

scheming freedom

from labour

and stone.

The imagination must scheme because the imagination, by definition, will reject the imposition of conventional order and morality. The imagination seeks to create the new and the unconventional. The amoral and unconventional spirit will reject the conventional morality and  order implied by “labour and stone”. The stone can be understood as the inflexible and implacable order of the church. The mention of labour, in combination with the stone, is possibly an allusion to the myth of Sysiphus — a rich and appropriate allusion. In other words, the poem is comparing the lifeless preoccupation of the respectable death to the labour of Sysiphus, who will always roll the same stone to the top of the mountain, but will never succeed in keeping it there.

order implied by “labour and stone”. The stone can be understood as the inflexible and implacable order of the church. The mention of labour, in combination with the stone, is possibly an allusion to the myth of Sysiphus — a rich and appropriate allusion. In other words, the poem is comparing the lifeless preoccupation of the respectable death to the labour of Sysiphus, who will always roll the same stone to the top of the mountain, but will never succeed in keeping it there.

The stone will always roll back to the bottom and Sysiphus will push it, again and again, back to the top. The task is insoluble. Likewise, the Janus-like preoccupation with a respectable death is insoluble. The mystery of death will never be solved. The only solution is to free oneself from any Sisyphean preoccupation with death and live freely in the now, in the rosy and lovely cheek, the exhaled breath, the burly sun, and the body. Leave behind the dessicated symbolism of bread and wine. Free your imagination.

The poem may be understood as contrasting (and preferring) the amoral, anarchic and joyful now of the body against the slow and certain death of a soulless conventionality confined by tradition and fear — what he calls “this death” and a “respectable death”.

August 10 2013 • up in Vermont

lawrence ferlinghetti & free verse done right

in my opinion

Here’s a poem I’ve been meaning to write about.

As far as I’m concerned, it’s one of the gems, one of the masterpieces of the latter 20th century. There’s not a word out of place. I’m sure there are more but (because I spend more time writing than reading) I don’t know about them (unless other readers tell me).

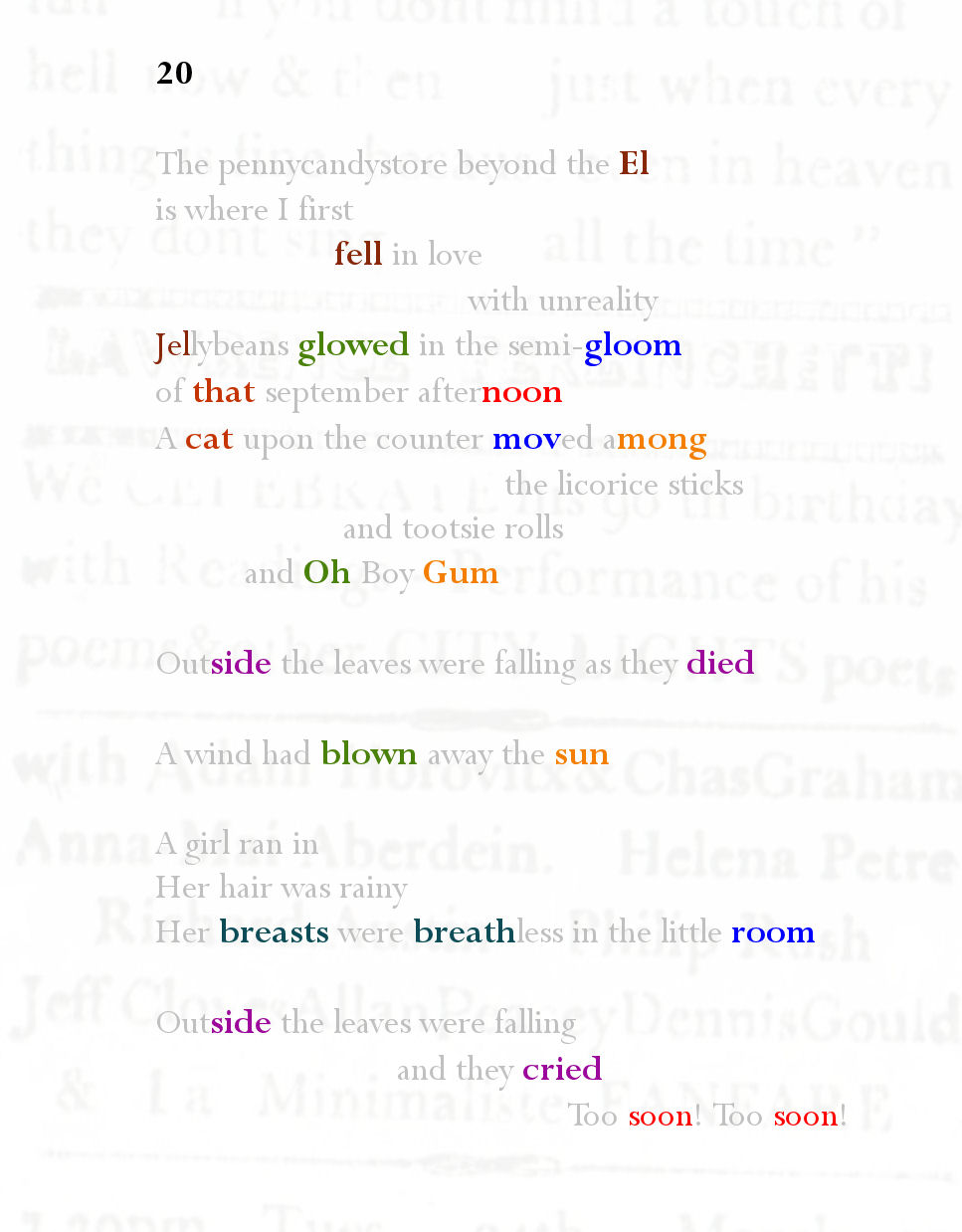

First, to the poem itself, then I’ll take a closer look at it. The poem is number 20 in Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s book A Coney Island of the Mind, a book considered by many to be his finest.

rhyme in free verse

The expressive power of rhyme is something many free verse poets either don’t get, don’t want to get, or lack the talent to realize (in my opinion). But there are poets writing in this genre who do get it and Ferlinghetti is one of them. The poem above is rich in end-rhyme and internal rhyme, and the rhyming isn’t gratuitous.

It adds expressive power and underscores the meaning of the poem. It makes the poem more memorable. Here is the same poem. I’ve highlighted the end rhymes and internal rhymes that strike me as the most important. There’s no significance to the colors except that like rhymes are similarly colored.

The first thing to know about good rhyme is that it doesn’t have to end-rhyme – especially in free verse. Metrical poetry can use internal rhyme as well, but the advantage that free verse offers is the freedom of its line lengths. The freedom allows a poet like Ferlinghetti to place the rhyme exactly where he wants them.

The words among and gum are assonant rhymes, meaning that only the vowel sounds rhyme.

In a metrical poem, if Ferlinghetti had wanted to keep these rhymes as end rhymes, he probably would have had to drop some syllables. And that brings to mind another little secret (which I’ll let you in on). This “free verse” poem has a metrical poem hidden inside it.

If I move some lines around, watch what happens. Watch this:

20

1.) The pen|nycan|dystore| beyond |the El

is where | I first fell |in love |with un|real|ity

Jelly|beans glowed |in the se|mi-gloom

of that| septem|ber af|ternoon

5.) A cat |upon |the coun|ter moved |among

the li|corice sticks |and toot|sie rolls |and Oh |Boy Gum

Outside |the leaves |were fal|ling as |they died

A wind| had blown |away |the sun

A girl |ran in |Her hair |was rainy

10.) Her breasts |were breath|less in |the lit|tle room

Outside |the leaves |were fal|ling and |they cried

Too soon! |Too soon!

In terms of Iambic Rhythm, this poem is more regular than Keats! I read lines 1,5,7,10 & 11 as Iambic Pentameter. And I read lines 3,4, 8 & 9 as Iambic Tetrameter. Lines 2 & 6 are alexandrines (6 foot lines rather than 5 foot lines). The red represents a trochaic foot. The blue represents an anapestic variant foot and the green would be a feminine ending (just as with all my scansions). I chose to scan the final line as Iambic Dimeter. (This isn’t the only way to scan these lines but reflects what makes sense – to me.)

All in all, this poem could easily be a regular stanza in a larger traditional poem. Many, though not all, of Ferlinghetti’s poems in A Coney Island of the Mind are “subversively” metrical. And many younger poets would do well to learn by it. The techniques of traditional poetry are still available to all poets, even those who write free verse. They’re not exclusionary – though one might quibble as to whether Ferlinghetti’s poem is truly “free verse”.

What’s truly sweet about Ferlinghetti’s rhymes is how he withholds the rhyme suggested by gloom and noon to the very end of the poem.The other rhymes find their companions either within two or three lines, El & fell, that & cat, among, gum & sun, glowed, oh & blown; or the rhymes occur within the same lines, outside & died, breasts and breathless. The internal rhymes breasts and breathless are a masterful touch. (The alliteration underscores that moment when the boy sees something besides candy, better than candy, and like candy.)

Only gloom and noon remain unrhymed, but the ear has been primed.

And it’s when the poem closes that gloom and noon are rhymed. The effect is one of framing and also of completion. The rhymes subliminally reinforce the poem’s closure, especially the repeated soon. In a sense, Ferlinghetti has created a pattern that seeks closure both in subject matter and form.

This is what rhyme can add to a poem.

And this is what is missing in so much free verse – the subtle parallelism of rhyme, meter and meaning.

imagery and meaning

or the other reasons the poem is a masterpiece

The pennycandystore beyond the El

From the very first line we’re reminded of innocence and simplicity. What could be more benign than the pennycandystore? And what is the El? It probably refers to one of the elevated subway lines of New York City’s transit, but it could also refer to the “L” of Chicago, also called the “El” (by some Chicagoans). If I were the betting kind, I would put my money on New York. Lawrence Ferlinghetti was born in Yonkers (just north of New York City)  and so (one would expect) would have been familiar with New York City subway system as a child, (although this assumes that the poem as autobiographical.)

and so (one would expect) would have been familiar with New York City subway system as a child, (although this assumes that the poem as autobiographical.)

On the other hand, though the title of the book would seem to locate the poetry in New York City, some of the opening poems locate the speaker in California. Additionally, Ferlinghetti tells us that the book’s title is taken from Henry Miller’s Into the Night Life, making the title more an idea than a place. I’ve noticed that readers from Chicago assume that Ferlinghetti is describing the “L” in Chicago while readers from New York assume it’s New York.

To make matters worse, there has been more than one “El” in New York. There’s the Ninth Avenue “El”, there’s the “El” station which was demolished in 1940 (but which Ferlinghetti must have known), and then there’s the “El” of Jamaica Avenue in Richmond Hill, Queens. To me, the demolished El station seems a likely candidate; but it doesn’t matter. If Ferlinghetti wanted us to know, he could tell us. As of writing this, he’s still around.

is where I first

fell in love

with unreality

What does the poem mean by unreality? The poem gives us some clues:

Jellybeans glowed in the semi-gloom

of that september afternoon

A cat upon the counter moved among

the licorice sticks

and tootsie rolls

and Oh Boy Gum

Was it the jellybeans glowing in the semi-gloom? But there’s little else “unreal” in the description. Here’s how I read it: The poet is a boy when he walks into the pennycandystore. Reality, to him, are the glowing jellybeans, the licorice sticks, the tootsie rolls and the Oh Boy Gum. The jellybeans glow, like beacons. But another kind of reality (and unreality to the boy) begins to swirl around him. It’s in the semi-gloom of that septemeber afternoon. It’s the cat upon the counter, moving like a huntress through the boy’s “reality”, through the beckoning jellybeans, licorice sticks and “Oh Boy Gum”. Oh Boy… Ferlinghetti’s choice of candy is no mistake. This is candy for a boy. This the stuff that makes a boy say, oh boy…

Outside the leaves were falling as they died

A wind had blown away the sun

But unreality will not be delayed; and there is more dying than just the leaves. The boy’s reality, his pennycandystore, is also dying. The sun, and all that it has represented to the boy, is being blown away by a wind – and that wind is more than just a literal wind. Something else is about to dissolve the boy’s reality – and unreality:

A girl ran in

Her hair was rainy

Her breasts were breathless in the little room

Need I say more? Ferlinghetti says it best, and I can’t think of any boy who hasn’t had that same experience, that same breath-stopping, heart stopping, unreal instance when we see “a girl” for the first time. She has run in and she carries, into the little room, all of the unreality the boy had, until this moment, been unaware of. Her hair, the rain that sheds the leaves and has blown away the sun, and her breasts. And what is breathless in the little room? Her breasts? Him? The little room? Where are the jellybeans? – the licorice, tootsie rolls or “Oh Boy” gun? They are gone, like so much else. Gone.

Outside the leaves were falling

and they cried

Too soon! Too soon!

The poem moves us out of the pennycandystore. There’s no need to tell more. Where a lesser poet might have remained inside the store, telling us more than needs description, Ferlinghetti’s touch is masterful – genius. We know. The boy is gone, in love with an unreality, the sudden unfathomable and breathlessly indefinable beauty of a girl. The pennycandystore, with all its little childish realties, is gone. Outside, the falling leaves cry: Too soon! Too soon!

afterthought

Having written Let Poetry Die and posts like Hey, David Orr!, I can’t help but add this extract from Ferlinghetti’s poetry:

From Ferlinghetti’s Populist Manifesto Number 1

Where are Whitman’s wild children,

Where are Whitman’s wild children,

where the great voices speaking out

with a sense of sweetness and sublimity,

where the great new vision,

the great world-view,

the high prophetic song

of the immense earth

and all that sings in it

And our relations to it –

Poets, descend

to the street of the world once more

And open your minds & eyes

with the old visual delight…

Horsegod: Collected Poems by Robert Bagg

- In exchange for a complimentary copy, I expressed interest in reviewing poetry by poets “in exile” – the self-published. Specifically, I was looking for poets who trade in meter or rhyme, the disciplines of traditional poetry. This book, Horsegod, by Robert Bragg, was the first book I received. What a great way to start.

Me? A reviewer?

And in addition to this book, I have two more books to review. I ask myself: What if it were my own poetry? No poet wants a comment that discourages readers from reading their work.

I favor criticism that analyzes poetry on its own terms rather than according to the tastes of the reviewer. For an idea of what I mean, check out my post on Marjorie Perloff’s criticism. (What poet wants to read that his or her rhymes are too simplistic when that is precisely the kind of rhymes they are pursuing.) Poets make aesthetic choices, and my own philosophy is not to criticize them for that – but to observe.

Let’s see how I do.

About Robert Bagg

Just a couple words, because there’s a perfectly good biography of Bagg at his own website. The thing worth noting (and to my profound envy) is that he met and studied with Robert Frost.

At Amherst he had the good fortune to study with Walker Gibson and James Merrill and to alarm Robert Frost, who chided him for writing about sex, noting that Yeats waited until old age to broach that aspect of experience.

I don’t know to what extent he studied with Frost or the others, but just to have met the great poet sends me into a tailspin of jealousy. Also worth noting is the experience Bagg brings to his poetry.

After a semester at Harvard he earned a Ph.D. in English at the University of Connecticut, taught briefly at the University of Washington (1963-65), and then for the rest of his career at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst where he served as Department Chair from 1986 to 1992. His teaching specialties were English Romantic Poetry, Modern Poetry, and Great Books from Homer to Hemingway.

A Limber Lope

To give you an idea of the kind of poetry you can expect to find, here are the final lines of a Sonnet called Caption for a Wire Photo:

To give you an idea of the kind of poetry you can expect to find, here are the final lines of a Sonnet called Caption for a Wire Photo:

(…)machine gun slugs

seek out his jacket and rip up her dress;exposed while sprinting for a house safe

from this blood-starved cancerous regime—

enraged by a remission all too brief—

their drab lives shed like debris from a dreamthey click a neutral camera and point-blank rifle,

feel a shrill heaviness, and are forever still.

The rhyme scheme is that of a Shakespearean Sonnet but Bagg dispenses with an accentual/syllabic meter – normally Iambic Pentameter. He opts for a syllabic line (counting the number of syllables per line). His rhymes combine true rhymes, slant rhymes and wrenched rhymes – reminding one of Emily Dickinson’s approach.

For this reason, his verse will read as rough, muscular, and knotted. But there is maturity in his choices – he’s an experienced poet whose stylistic choices are controlled and deliberate. He avoids an overly end-stopped verse, doubtlessly made easier by the use of a syllabic line and a variety of half-rhymes. The overall effect is of a poet who blends free verse and traditional poetry. A visit Bagg’s homepage confirms as much:

Bagg also often takes advantage of the freer practice of the twentieth-century, since the “freedom” it encourages allows for plunging ahead when necessary with little heed for decorum.

It does grant the poet greater latitude, but also surrenders some of the effects unique to meter (accentual syllabic) and true rhyme. Nevertheless, Bagg is a model for the younger poet. There is a middle ground between the traditional and free verse aesthetic.

I suspect Bagg is commenting on his own poetics in this seemingly whimsical poem Girl with Her Pigtails Crooked.

Her left leg lagged behind the right,

a firm step followed by a limp.

Her pigtails haggled down her neck

like lines of tangled hemp.

I watched the shameless way she lamed,

She needn’t limp so lumpily,

I thought, so I called down to her,

“Hey, you don’t need to limp!”

She let her hair have its head —

it went its separate ways—like rope

let out to trim a coming storm

She stepped into a limber lope.

Think of the pigtailed girl as this little poem and Bagg as the boy who calls down to her: “Hey, you don’t need to limp!” He lets his rhyme and meter, like the girl’s hair, go its separate ways, like “rope let out to trim a coming storm”. His little poem steps into a limber lope, a characterization that could apply to all of his poems.

Some Brief Narration

One of the showpieces in Bagg’s book is a narrative poem called The Tandem Ride. You can read the poem in its entirety by visiting Bagg’s webpage: Robert Bagg: Poems, Greek Plays, Essays, Novels, Memoir. The narrative poem is a genre almost altogether forgotten and, though I may be wrong, I suspect that poetry journals are largely to blame. While the great variety of journals provide a venue to an equally great variety of poets, their interest in poetry is a very limited kind: short; something that will fit politely fit the page.

Some journals limit poems to as little as 25 lines, at most, two pages, but reluctantly. Many of my own poems are eliminated simply by virtue of their length.

The results are obvious. The birth of the poetry journal, of which there are hundreds, coincides with the  ubiquity of the short lyric. The long, sturdy narratives of the romantics and Victorians gave way to short lyrics and confessionals that neatly fit the pages of the poetry journal. Poetry Magazine recently issued a collection of poems been published in their pages since their founding in the early 20th Century – The POETRY Anthology, 1912-2002. All but a handful of the poems fit neatly on the page.

ubiquity of the short lyric. The long, sturdy narratives of the romantics and Victorians gave way to short lyrics and confessionals that neatly fit the pages of the poetry journal. Poetry Magazine recently issued a collection of poems been published in their pages since their founding in the early 20th Century – The POETRY Anthology, 1912-2002. All but a handful of the poems fit neatly on the page.

Nearly all the poems hum along in the first person or first person plural.

Reading POETRY’s anthology reminds me of the dusty old anthologies from the Victorian Era, proudly full of competent period pieces and timely poets – all of which and all of whom are forgotten by the next generation. They’re easy to find. Just look in any used bookstore. You can almost smell them.

Although I haven’t searched exhaustively, I’ve only found one or two stories in nearly five hundred pages of poetry (all among the very first poems published by the periodical) and they are also among the few not written in the first person. These are the better known poems. One is by Robert Frost – his The Code – Heroics. The other is by T.S. Eliot, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. As the 20th Century progressed, poetic ambition seems to have grown smaller and ever more forgettable.

Bagg’s effort is a welcome departure. His Keatsian or Spencerian stanzas (depending on how they’re appraised) nicely carry the narration forward. They’re enjambment, made easier through the use of off-rhymes, helps the poem succeed where others fail.

She pushes a glass door open a crack,

emerges from a tropical greenhouse,

shoes squishing, then pauses – almost goes back-

aware her sweat-drenched translucent blouse

would amuse us, or might even arouse

us more than her breasts did normally.

She’d never say, Come on to me, guys, now’s

the right time! — but I sensed viscerally

she wasn’t the same girl we had chased up that tree.

This is a stanza of almost perfect rhyme (greenhouse and blouse is a wrenched rhyme), but the content and language are thoroughly modern. So many modern poets who write with meter and rhyme seem unable to combine the disciplines with a modern vernacular. Once again, the lack of meter (I don’t normally consider syllabics a meter) and off-rhymes give the poem an almost free verse feel. In some cases, the combined effects buries the rhymes. It’s a deliberate effect.  Some will like it, some won’t. Don’t come to his poetry looking for soaring melody. His voice is modern and rigorous.

Some will like it, some won’t. Don’t come to his poetry looking for soaring melody. His voice is modern and rigorous.

In this book, at least, it’s not until the very last pages that this narrative impulse reappears and then on a much smaller scale. That’s somewhat of a disappointment to me, but may not be to other readers. Another disappointment is that the subsequent poems are primarily first person. Some address a “you”, but they all have the feel of a poet discussing himself. I wouldn’t call them confessional, though that term can be broad. There’s an element of confessionalism in all of his poems – but never self-pity.

The Heart of Bagg’s Poetry: His Imagery

And now we really get into the meat of Bagg’s poetry.

Bagg’s imagery is full of physicality and motion, is full of the body. As in his imagery, so too in his poems. He his not a poet, like Keats, at ease with ease, contemplation or sensuality (all qualities that later poets during the Victorian era considered effeminate). Bagg’s physicality won’t be restrained.

In Be Good, the child “hugs the intolerable boulder/has muscled uphill since birth”.

The world he prefers to observe is also full of kinetic energy.

My iron is wide; you use your blessed driver

and hit it with your fullest strength,

skimming the club heads so close to the earth

I hardly hear your shot, but see it fly

over everything toward the green… (My Father Plays The 17th)

In describing a couple’s decision to marriage, his analogy is full of athleticism:

Ashley and Melissa, you have circled

marriage like a distant challenge–

a mountain ripe for climbing–plotting,

perhaps, a night approach across

a secret valley… (A Toast for Ashley and Melissa)

Bagg’s eye is drawn to sport and action (as in this translation from Sophocles Elektra):

Reacting quickly, the skittish

Athenian pulled his horses off

to one side and slowed, allowing

the surge of chariots tot pass him.Orestes too had laid off the pace,

in last place, trusting his stretch run.

But when he saw the Athenian,

his only rival, still upright, he whistled

shrilly in the ears of his quick fillies

to give chase. The teams drew even,

first one man’s head edging in front,

then the others, as they raced on. (Chariot Race at Delphi)

In the powerful and substantial lines of his poem An Ancient Quarrel, Bagg turns an appraisal of Yeats into a titanic wrestling match:

You might be stirring forces hard to quell–

that thrill exploding in your abdomen

when a trapped quarry turns his fear on you.

You go in flailing hand to hand, frenziedbecause your own survival’s now at risk.

His barbarous thrusting voice impales you

deep in the place from which your war-cry soars.

Now its the pure joy of battle driving…

Notice words like exploding, trapped, flailing, thrusting, impaling. One might object that words like these are only to be expected given the subject matter. I don’t argue the point, except to say that Bagg is also in control of the subject matter, and gravitates toward the physical, the muscular, the strain of motion. He has an eye for it.

It’s no wonder, as with the very first poem cited in this review, that Bagg, more than once, is drawn to the topic of war. He doesn’t valorize or glorify war (very much the opposite) but his sensibility is drawn to the physicality of war, and its horrors.

And it’s also no wonder that Bagg shocked Frost with the sheer physicality of his poetry’s sexual content. The poem Cello Suite , the closest Bagg comes to pure lyricism, is nothing if not a celebration of the sensual physicality of sex and procreation:

Cheek to her cello’s gnarled scroll,

impulsive

irretrievable love,

once wildly made, crests,

then calmly overflows

the cello rosewood curves.As she lifts her bow to the skies

her lover’s hand slides

under her shoulder,

her breasts lift

to his passing forearm.

(Unfortunately, WordPress doesn’t allow me to reproduce the layout of the poem.)

In the lovely lines of his poem Twelfth Night:

If music be love’s food, disguise

must be love’s speech, each wanton thrust

engendering a gentle parry–

a playfulness that implicates

interested parties wearing tights.

At the start of this poem Bagg praises Viola’s masculine pluck, and one gets the feeling that this is no idle praise – that this is precisely the thing that has drawn the poet’s eye to this character – her masculinity, her insinuated physicality. There is nothing Keatsian or feminine about her (though there is and he knows it). In this poem, at least, there is an unmistakable homeroticism that Bagg clearly enjoys and with which he is beguiled.

But Bagg’s eye for physicality carries a price. In the entirety of Twelfth Night and Cello Suite, for example, the reader never once smells. There’s no taste and, oddly enough, there’s no sensation (touch). Bagg prefers motion, sometimes repetitively, where he might have evoked a different sense:

“her sliding tears/reflect her mother’s”

“her lover’s hand slides/under her shoulder”

This isn’t to say that Bagg never evokes the more effeminate senses (as Victorians called them) but never with the same eye for the physicality of the body and the world.

Now he’ll go.

His body hardens with still-clenching muscle.

I edge my right heel back along his side,

tuck my head to his neck, feel his ears poke

out straight, and out of rotting earth we churn-

reanimated halves of the one beast

both off us want mightily to be: the Horegod.We pound through reeking sludge and angry bush

that claws at our face, snags our thrusting legs.

We are joy pulsing through a line of verse!

Even in these lines, the word reeking has more the feel of a physical assault than an appeal to our sense of smell. In what way does it reek? What does it reek of? Bagg doesn’t tell us.

As with Bagg’s revelry in sexuality, it should come as no surprise that the physical decline of age is an experience that Bagg feels keenly – it’s slowing and diminishing vigor.

…age so

intensifies what’s left

of our skills and passions,

we linger over them

with apprehensive

appreciation–

as over a single malt’s

evanescent bouquet.We fear the softening

of our golf swing

will put even the easy

carries beyond our reach;

that lovemaking’s

strife will become

affectionate peace… (Bittersweetness)

Bagg is not at ease with an affectionate peace, her fears it. Lovemaking, to Bagg, is strife, of both body and mind. His poetry, a lovemaking of its own order, is full of strife and motion. These are qualities the reader can expect in Bagg’s work. There is more than a touch of Hemingway in Bagg’s vigorous verse and he draws out the comparison himself:

Now that your honed survival skills assert

themselves, ask fellow Hemingwayfarers

this: When the powers in your loins and mindwane, should you punish both with a twelve gauge?

Or keep on brining dark bulletins back

from our last war zone–as Phillip Roth does

(who holds the title Hemingway renounced),

determined to die ringside to himself

matched with an unbeaten serial killer. (Heavyweights)

Younger poets and readers looking for a model – for a poet who makes vigorous and muscular use of rhyme and sometimes meter – couldn’t do better than read Bagg’s verse. His language and poetry is modern, forceful, and uncompromising.

Bagg on the Internet

- Visit Bagg’s Homepage for links to other books, opinions and more poems.

- Bagg takes exception to David Orr’s opinions on Political Poetry.

- Three of Bagg’s Poems brought to you by the Brockton Public Library

- The Oedipus Plays of Sophocles: Oedipus the King, Oedipus at Kolonos, and Antigone – Translated by Robert Bagg

The Seven Tales of the India Traders: The Sixth Day

Told on the sixth day, after Lon Po’s Tale of the Fifth Day

Tsi Tung’s Story

Once again winter has not caught us in the mountains. Let us admire the moon. She keeps the skies clear. Is it not true that our poet Li Po drowned when he tried to embrace the moon’s reflection in water? My father used to recite a poem (I can only recall the beginning); it was in autumn, on a night like this, when the moon is brightest. We shook laurel blossoms down. We made dumplings. We powdered rice and peanuts and rolled them with sesame. Then we drank wine, as we do tonight, and peered at the moon. This is how my father’s poem began:

It must have been beautiful

As the first of those evenings when frost

Gives way to petals;

When their fall is mingled

With the meeting of moths rising toward the light.

Or was it “the melting of moths”? But this is what my story is about — the moon and moths.

The Crescent Wing

Su Shir had seen the princess. It had been a mistake. He told no one. It was forbidden to look on the royal family.  The great palace itself was walled and hidden to the view of any man or woman. Su Shir made paper. His skill throughout Beijing was unmatched. Yet now, when he was not fashioning the paper for which he was commissioned, he used it to craft tiny animals. One day when he knew the princess would be passing he left a paper crane in the street. It was forbidden to remain in the streets when the royal family passed.

The great palace itself was walled and hidden to the view of any man or woman. Su Shir made paper. His skill throughout Beijing was unmatched. Yet now, when he was not fashioning the paper for which he was commissioned, he used it to craft tiny animals. One day when he knew the princess would be passing he left a paper crane in the street. It was forbidden to remain in the streets when the royal family passed.

The princess saw the paper crane. She asked that it be picked up and given to her. When she peered at it closely she was delighted by it. Yet none among those who accompanied her knew by whom it had been created. She put the paper crane into a pocket of her robe. Many days passed before she noticed it again. She laughed for now for it seemed to her a trifle. When evening came she held it to the flame of a candle. “Ah,” she said, “do you see the beautiful green flame it makes?”

As Su Shir slept that night a nightingale came to his window. She sang to him as he dreamed. “The princess is an idle girl who has burned your paper crane.” When Su Shir awoke the next morning he recalled the nightingale’s words as though he had dreamt them. “I am a idle craftsman,” he said, “who shall remember me whether or not I make paper crane’s for an idle girl?” And each day after he had finished his chores he crafted tiny cranes and such was his skill and artistry that they were imbued with life. “Seek light my little ones,” he said to them.

When he lay down to sleep the tiny cranes flew through the windows of Su Shir’s home and into the starlit night. They flew above the city and over the palace walls. And when they came into the princess’s palace room they flew into the flames of her tiny candle. One by one they vanished in a burst of green flame. The princess marveled at these tiny creatures and stayed awake long into the night to watch them fly into the flames.

When one night the princess’s father discovered the paper cranes he grew furious. “Find the maker,” he cried, “and bring him to me!” After the passing of a week the Emperor’s guards returned with Su Shir. They brought him before the Emperor and the little man trembled. He fell to his knees and bowed daring not to look. “Tell me why you send these paper cranes to my daughter?” he demanded. “For I have looked on your daughter,” he answered fearfully, “and I loved her.”

“Do you not know it is death to do so?” demanded the Emperor. “I do,” answered Su Shir. “Yet my daughter asks that I do not take your life,” said the Emperor. “I will take your sight instead.” Then Su Shir was blinded. The guards carried him outside the palace and threw him into the street. He might have wandered through the streets and never found his way if it were not for the nightingale. The bird sang to him and as he followed her song she led him back to his house.

He lay down then and did not rise again the next day nor in the week following. He might have remained so had not a visitor come to him in the night. The sound of small feet and a young girl’s voice woke him. “Do not cease to make your moths,” she said, “for though you must not send them to me, it was not for me you made them, poor man, but for love.” Then Su Shir felt a tear strike his cheek. The princess wept. He felt her kiss his closed eyes and then his lips. Then she left and Su Shir rose from his bed.

He worked all night. He knew by finger’s touch which papers were the finest. He crafted a thousand of the tiny moths and before he slept he opened the doors and shutters of his house. “Go,” he said. “Go out.” Then they flew into the night. The princess did not see them. They did not fly over the palace walls. They saw the moon and they flew after the moon until their paper wings became like crystalline tear drops. In autumn, when they finally reached the moon, they were countless in number and their wings made the moonlight seem almost as bright as day. And the princess, in her father’s garden, could see the white blossoms on the laurel tree at night. Then the moths shed their wings and the wings fell like flakes of snow and fell each year thereafter, as each year more moths flew to the moon and shed their wings.

Here Ends Tsi Tung’s Tale

Ah, now I recall how my father’s poem ended.

Li Po leaned into the water

Drunk with drink and fellowship,

To scoop the moon into his hands;

To bring it to his lips

And finally sip the liquid of its light….

Let us look at the moon tonight, my friends, and think on who will remember us when we are gone.

Followed on the Seventh Day by Lao Chi’s Story.

A Sex Primer

Opening Book: Spider Spider Page 30

Opening Book: The Fox Watches the Moon Page 27-28