my other new book…

As promised, my other post about poetry and women (my two favorite subjects). The previous post was about the treachery of women. So, my other summer reading is How to Read Chinese Poetry: A Guided Anthology. The “book” is workbook sized (which means it’s about the size of a college workbook) and I’ve only just begun it.

As promised, my other post about poetry and women (my two favorite subjects). The previous post was about the treachery of women. So, my other summer reading is How to Read Chinese Poetry: A Guided Anthology. The “book” is workbook sized (which means it’s about the size of a college workbook) and I’ve only just begun it.

The history of poetry in China is astounding. For hundreds (perhaps thousands) of years no one with any governmental ambitions could advance to even the most menial position without passing an arduous exam predicated on a thorough knowledge of poetry (and literature in general). Poetry was tremendously valued and esteemed to a degree (in its longevity) unmatched by any other culture. The history of English poetry pales in comparison.![]()

Part of the reason, I think, comes from the continuity of Chinese writing & language. Unlike the Western Alphabet, Chinese script doesn’t reflect pronunciation. Any given symbol (such as the moon) could remain essentially unchanged for hundreds of years. If Elizabethans wanted to read poetry from a thousand years before, they needed to learn the actual languages – Latin, Greek or Anglo-Saxon because western writing reflects pronunciation. A Chinese poet, on the other hand, only needed to be literate. If we used a similar system in the west then all of us could read and understand classical languages (though we wouldn’t know anything about the original Latin and Greek words). Similarly (and setting aside issues of grammar) any western reader can learn to ‘read’ Chinese without speaking the language. The moon is the moon is the moon.

What got me thinking about this post were some comments in the introductory material:

“Love and Courtship” is a prominent theme in the airs of the Book of Poetry [the earliest extent collection of Chinese poetry]. Many of the airs are bone fide erotic love songs, featuring unabashed accounts of a tryst or an affair. In these songs , women show few signs of inhibition and, indeed, are often the daring and resourceful initiators of a secret affair. Such uninhibited, self-willed women are not seen in later literati compositions, with the exception of Yuan songs. In most literati compositions, women often fall into two rather static types: the beautiful and the abandoned. ¶ “The Beautiful Woman” shows how the literati reconceptualized woman as an abstract, static object of desire—for spiritual fulfillment, sensual pleasure, or both.”

Above · The sign for Woman from 1500 BC to the present. AncientScripts

Above · The sign for Woman from 1500 BC to the present. AncientScripts

And that’s interesting because this same abstract idealization of women also occurred (and occurs) in Western Literature (and probably in all cultures with an accumulated history of literature). Why? I suspect that the early and rambunctious poetry of erotic love is deemed too vulgar as art develops. The earliest poetry all seems to spring  from popular lyrics — consider modern rock, country and rap — and as “a literature” begins to establish itself (separate itself) and come into contact with more patrician and aristocratic circles, it’s possible that erotic poetry is considered too gauche and unrefined. In general, all cultures place a premium on the spiritual as a more fit pursuit for philosophy , art, music and literature. How do women fit into such otherworldly pursuits? Uneasily. And usually (or at least historically) it’s because men are doing the defining.

from popular lyrics — consider modern rock, country and rap — and as “a literature” begins to establish itself (separate itself) and come into contact with more patrician and aristocratic circles, it’s possible that erotic poetry is considered too gauche and unrefined. In general, all cultures place a premium on the spiritual as a more fit pursuit for philosophy , art, music and literature. How do women fit into such otherworldly pursuits? Uneasily. And usually (or at least historically) it’s because men are doing the defining.

- The renaissance angel at left could be a woman or a young man. The book Angels in the Early Modern World has this to say: “Other definitive assumptions about angels also began to crystallise in the early centuries of the Church. Angels were asexual spiritual beings, though they usually took the outward form of young men. An idea only partially attributable to Scripture – that angels appeared as winged creatures – was becoming an almost universal iconographic convention, as angels were increasingly depicted in wall painting, sculpture, and manuscript illumination. The very question of whether these figures could legitimately be represented in art was definitively settled in the affirmative by the second Council of Nicea.” The effect, ironically or perhaps deliberately,

is to eroticize spiritual iconography and spirituality itself- not just through the representation of women and girls, but men and boys. In other words, the perfect woman (the angel) is homoerotic as well.

is to eroticize spiritual iconography and spirituality itself- not just through the representation of women and girls, but men and boys. In other words, the perfect woman (the angel) is homoerotic as well.

The exclusion of women from the inner sanctum of spiritual and religious practice isn’t isolated – Christians, Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, Taoists (inasmuch as Taoist sects have organized), Hindus, etc… The presence of women among men gives rise to the inevitable: they become objects of lust, they arouse and are desirous, emotions that just don’t jibe with otherworldly detachment and contemplation. It’s no wonder women have been excluded. Millions of years of evolution seems more  than most men can overcome. Easier to hide women away, exclude them or, in the case of literature, idealize them, than be around them. They become paragons of untouchable virtue and beauty. The literature pretends to ignore the raw, physical and erotic allure of women’s femininity (just as religious iconography asexualizes them). They become the angels of Renaissance painting. They symbolize an archetypal otherworldly beauty acceptable because it is, in theory, detached from physical longing. They are an idealized representation of the spiritual pursuit – it’s detached beauty. I write in theory because the iconography, ironically, transforms the other-world beauty of angels into its own kind of eroticism and homoeroticism.

than most men can overcome. Easier to hide women away, exclude them or, in the case of literature, idealize them, than be around them. They become paragons of untouchable virtue and beauty. The literature pretends to ignore the raw, physical and erotic allure of women’s femininity (just as religious iconography asexualizes them). They become the angels of Renaissance painting. They symbolize an archetypal otherworldly beauty acceptable because it is, in theory, detached from physical longing. They are an idealized representation of the spiritual pursuit – it’s detached beauty. I write in theory because the iconography, ironically, transforms the other-world beauty of angels into its own kind of eroticism and homoeroticism.

- Angel by Abbott Handerson Thayer. The painting at right comes from the end of the 19th century and early 20th . Thayer was known as a painter of Ideal Figures and his paintings of angels are his most popular and critically recognized. The painting at right is the most famous. No other painting before or since so beautifully captures the ineffable beauty that both eroticizes and denies the erotic. The model was his daughter Mary, but absent that knowledge, it’s not unreasonable to wonder if the model was a boy. Her youth encourages a certain asexuality.

Anyway, this is my stab at some sort of explanation for the idealization of women in art, philosophy and religion. More than this requires a degree in gender studies and sociology. However, I suspect that this impulse to “asexualize” women is all part of the same spectrum (whether in art or religion). It is a desire to transform or redirect physical desire and it’s a hard place for women to inhabit. The result is that women are seen as either/or, either angels or as devils. Everything in between gets lost: girlhood, their own desires, romance, sex, childbirth, motherhood, marriage, housekeeping. That’s why Anne Bradstreet’s poem, Before the birth of one of her children, is so important.

The image at left is one that I found on the web. I don’t know whom to credit but clicking on the image will lead you to one possible source. There’s something about this image that appeals to me. It’s as if the conventions – the concealments and misdirections of two thousand years – have been, like clothes, stripped away. The woman behind the iconography is revealed. But even so, a new ambiguity confronts us. What do you feel when you view her? Strength or vulnerability? Eroticism or reticence? We are invited, perhaps, to recreate the angels of our desire and spirituality. Who will she be? Will she be permitted into the inner circle of our theologies – as we have made and make her? – or as she is?

The image at left is one that I found on the web. I don’t know whom to credit but clicking on the image will lead you to one possible source. There’s something about this image that appeals to me. It’s as if the conventions – the concealments and misdirections of two thousand years – have been, like clothes, stripped away. The woman behind the iconography is revealed. But even so, a new ambiguity confronts us. What do you feel when you view her? Strength or vulnerability? Eroticism or reticence? We are invited, perhaps, to recreate the angels of our desire and spirituality. Who will she be? Will she be permitted into the inner circle of our theologies – as we have made and make her? – or as she is?

The West’s Book of Poetry

The west’s poetic tradition, unlike China’s, isn’t confined to one language or society. It begins with the Greeks and Romans and from there their influence spread through the various languages of Europe.

The women of Rome, to judge by Ovid’s Amores, had more in common with China’s rambunctious women than anything idealized. Like the Chinese women, they “show few signs of inhibition and, indeed, are often the daring and resourceful initiators of [secret affairs].” One of my favorite poems by Ovid (for it’s eroticism and self-effacing good humour) was beautifully translated by Christopher Marlowe – the greatest poet and playwright after Shakespeare and the man who was, perhaps, also Shakespeare’s elder friend, collaborator and inspiration.

Ovid’s Sixth Elegy: Book III of his Amores • Christopher Marlowe

All of Marlowe’s translations of Ovid’s Erotic poetry can be found at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Interestingly, Ovid’s first version of the Amores (now lost) was longer and probably more explicit. Even within an artist’s lifetime, one sees a progression from the more to the less explicit.

The earliest “English” poetry is that of the Anglo-Saxons. (English, in this sense, refers more to the nation than to the language.) The degree to which the Anglo-Saxons were exposed to the great poets of Latin or Greek is debatable. However, the Anglo-Saxons were certainly exposed to Latin itself, both by the Romans and later by missionaries and their establishment of Christianity. Anglo-Saxon poetry doesn’t appear to have been influenced by the meters of Greek or Latin and I don’t know whether that was through ignorance of classical poetry or other reasons. The verse forms of Anglo-Saxon are those of its proto-germanic heritage.

The most popular and well-known understanding of Old English poetry continues to be Sievers’ alliterative verse. The system is based upon accent, alliteration, the quantity of vowels, and patterns of syllabic accentuation. It consists of five permutations on a base verse scheme; any one of the five types can be used in any verse. The system was inherited from and exists in one form or another in all of the older Germanic languages. New World Encycopedia

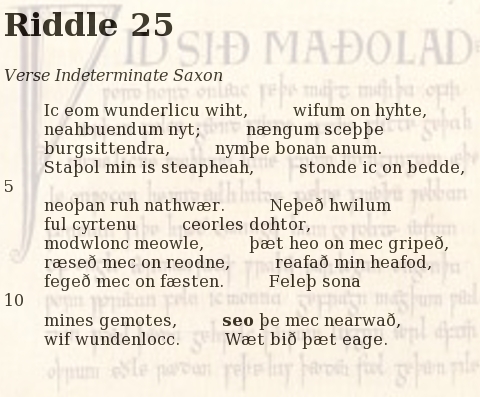

If Anglo-Saxon is to be considered the earliest poetry of the English language, then the Exeter Book of Riddles is the closest parallel to China’s Book of Poetry. Interestingly, and contrary to expectation, the position of women in Anglo Saxon society was more liberated (or more modern) than the ignorant barbarity of England’s 19th century legal practice. Whereas 19th century woman could expect to be left in poverty and destitution upon divorce (all their properties having become that of their husband). The women of Anglo-Saxon Britain (who were not slaves) were entitled to half their combined worth:

Within marriage, finances belonged to both the husband and the wife. This we know from wills and charters. Æthelbert’s law number 79 from the seventh century says about divorce:

If she wish to go away with her children, let her have half the property.

The greater equality of women is, I think, reflected the poetry of the Anglo-Saxons. There isn’t the same idealization of women that would become the Courtly Convention of Chaucer’s time (the literati’s equivalent to China’s abstracted “Beautiful Woman” with her loss of self-will) – a convention from which Chaucer worked to liberate himself. The Exeter Book is full of poetic riddles that hint at erotic and sexual relationships between Anglo-Saxon men and women:

The poem/riddle roughly translates as follows:

I’m the world’s wonder, for I make women happy

–a boon to the neighborhood, a bane to no one,

though I may perhaps prick the one who picks me.I am set well up, stand in a bed,

have a roughish root. Rarely (though it happens)

a churl’s daughter more daring than the rest

–and lovelier! –lays hold of me,

and lays me in larder.She learns soon enough,

the curly-haired creature who clamps me so,

of my meeting with her: moist is her eye!

(The answer to the riddle may not be what you think it is.) And here is riddle 54:

- The background image is from a painting by Peter Wtewael, 1620’s. The erotic iconography in the painting makes for some interesting reading.

The translation comes from Hullweb’s History of Hull (the translation doesn’t follow line by line):

A young man made for the corner

where he knew she was standing;

this strapping youth had come some way –

with his own hands he whipped up her dress,·

and under her girdle (as she stood there)

thrust something stiff, worked his will;

they both shook. This fellow quickened:

one moment he was forceful, a first rate servant,

so strenuous that the next he was knocked up,·

quite blown by his exertion. Beneath the girdle

a thing began to grow that upstanding men

often think of, tenderly, and acquire.

To the Anglo-Saxon man, the perfect woman resembles himself

The Elizabethans

The rambunctious celebration of women if not always as sexual equals then at least as gameful erotic partners didn’t reappear until the Elizabethan Era, some six hundred years later. The Elizabethans were probably unaware of Anglo-Saxon poetry. Their models were the classical poets of Rome and as far as they were concerned, they (meaning they themselves) were the beginning of English literature. They were aware of Chaucer and Gower but they generally didn’t treat them as models.

The Elizabethans felt a more compelling link to the Roman poets with their mix of urbane wit, winking licentiousness and generous decorum. This was the poetry of empire and the Elizabethans were nothing if not a budding empire. Wit was the vapor the Elizabethans breathed. Sidney was first among the poets with his double-meaning erotic gamesmanship. That said, the reader of Sidney’s sonnets never gets a sense of Stella’s own desires and personality. She is only a vessel for Sidney’s sparkling wit.

Shakespeare, predictably enough, was the poet to breathe life into women. In his dramas, his female protagonists unabashedly match wits with men. The same liveliness can be found in Shakespeare’s Dark Lady sonnets 127 through 154. Here is Sonnet 130 (perhaps the most famous among them):

My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun;

Coral is far more red, than her lips red:

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun;

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head.

I have seen roses damasked, red and white,

But no such roses see I in her cheeks;

And in some perfumes is there more delight

Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks.

I love to hear her speak, yet well I know

That music hath a far more pleasing sound:

I grant I never saw a goddess go,

My mistress, when she walks, treads on the ground:

….And yet by heaven, I think my love as rare,

….As any she belied with false compare.

And it is with this sonnet that Shakespeare does something that no poet (with the possible exception of Ovid) did before him. He turns the Patrarchan expectation, that of the perfect and unattainable woman, on its head. The eyes of Shakespeare’s mistress “are nothing like the sun”. Her breasts are dun/dark, not white. Her hair is black and wiry. She has bad breath. And yet he can’t stay away from her. This sonnet isn’t about something as brittle as beauty or spotless virtue. For Shakespeare, a woman’s perfection something else – described in the omission. It is not in her eyes, her lips, her breasts or cheeks; and the same applies for us. We are, to each other, full of flaws and shortcomings; but it’s in imperfection that lovers mysteriously find perfection – and good humor. For all the eroticism, perfection and beauty in Petrarch’s Sonnets, they aren’t funny. (Besides which, the subject isn’t really erotic poetry, but the sense that women are equals in the affairs of men and women.) The Chinese Book of Poetry, Ovid’s Amores, the Anglo-Saxton riddle-poems, and Shakespeare’s Sonnets to the dark lady (all celebrating the imperfect perfection of men and women) are rich with wry smiles and outright laughter.

And this brings us to another reason for the abstract idealization of women. Western history teaches us that tragedy is high art and comedy is for the common crowd. Writing about women and men as they are seems to become, inescapably, the province of humor. Ipso facto, literati who wanted to be taken seriously wrote serious poetry; and serious poetry about real, imperfect women didn’t cut it. (Perfect women, it seems, may be beautiful, but they are humorless.)

And what were women writing?

And this is a huge subject.

The post so far hardly merits a starting point. And there are many cultures whose poetic literature I’m unfamiliar with – India for example or Russia. I don’t read all that much foreign language poetry because I don’t like modern translations. Too many modern “translators“ (heavy quotes) think its OK to translate the carefully structured verse of an original into lackluster free verse. Content isn’t enough for me. I like to get a sense for the language as well. That, to me, is what separates poetry from prose. Cervantes wrote that reading a translation was like looking at the back side of a Persian rug.

All of which is to say: If I haven’t mentioned poets I should have, it’s not because of an agenda.

Also, if any readers want to help me out and suggest other poets, please do.

That said, some poetry, I think, translates better than others. Haiku may be the most successfully translated if only because the haiku’s essence doesn’t reside in its language (to the same degree as a Shakespearean Sonnet) but in a kind  of poetic outlook or philosophy. This isn’t to say there’s no wordplay in haiku, but my feeling (which could be wrong) is that the brevity of the poetic form is friendlier to annotation where translation fails.

of poetic outlook or philosophy. This isn’t to say there’s no wordplay in haiku, but my feeling (which could be wrong) is that the brevity of the poetic form is friendlier to annotation where translation fails.

And what interests me about Haiku is what interests me about Japanese literature in general. Of all the cultures with which I’m familiar, the Japanese, historically, seem the most accepting of women poets. In China, by contrast, there were many women poets but, at least according to the book Women Poets of China, much of their poetry went unpublished if not destroyed:

Writing poetry was an essential part of the education and the social life of any educated man in ancient China, but it was not so for a woman. Most of the poems of those who did write were not handed down to posterity. Many women’s poems were shown only to their intimates, but were never published. In some cases, the poet herself (Sun Tao-hsüsm), or the parents of the poet (Chu Shu-chen), destroyed her work so that the reputation of the clan would not be damaged. Love poems usually led to gossip that the author was an unfaithful wife. Not until the Ching Dynasty ( 1644-1911) with the promotion of several leading (male) scholars such as Yüan Mei and Ch’en Wên-shu, did writing poetry become fashionable for ladies of the scholar gentry class. [p. 139]

On a Visit to Ch’ung Chên Taoist Temple

I see in the South Hall the List of

Successful Candidates in the Imperial Examinations (9th Century)

Cloud capped peaks fill the eyes

In the Spring sunshine.

Their names are written in beautiful characters

And posted in order of merit.

How I hate this silk dress

That conceals a poet.

I lift my head and read their names

In powerless envy.

Yü Hsüan-Chi [p. 19 Women Poets of China]

Japan, by contrast, seems to have been almost modern in its acceptance women’s poetry (if not women themselves). The world’s first (generally accepted) novel was written in Japan and by a women, Murasaki Shikibu, and is considered by most to be a work of genius. I’ve read it. I’m trying to encourage my wife to read it. But it’s not poetry, and curiously Japan never produced narrative poetry on the scale of an Iliad or Odyssey.

For whatever reason the Japanese aesthetic has always preferred shorter forms. Perhaps because of this, and because of the deliberately impersonal and ephemeral nature of haiku, the influence of gender is hard to pinpoint. Classical Haiku are not meant to be about the poet. The same autobiographical embarrassments that worried Chinese poets  didn’t apply to haiku. This, if for no other reason, probably made the haiku of women acceptable (if they were even recognized as being by women).

didn’t apply to haiku. This, if for no other reason, probably made the haiku of women acceptable (if they were even recognized as being by women).

It meant that the haiku poet Chiyo-ni (1703-1775) could travel the Japanese countryside like the great poet Basho (who died shortly before her birth). Whereas Basho clothed himself like a monk, Chiyo-ni travelled as a Buddhist nun. It’s worth noting also (and which may also have played a part in the acceptability of women poets) that there was no tradition of publications by individual poets. When haiku (or Tanka) were published, they were usually small print runs – anthologies of current poets. I’ve read that at the height of the form (mid 17th century) fully 1 in 20 of Japan’s population regularly wrote haiku. Anthologizing, I think, also made it easier for women poets to see their work in print. The result is that a poet like Chiyo-ni was appreciated, not as a woman poet (or not entirely) but on the merit of her poetry.

- It seems Chiyo-ni: Woman Haiku Master has become somewhat of a rarity, and that means Amazon resellers are trying to retire on it. The original price is $14.95 (I own it). If you want a copy and can find a copy close to that price, then you’re doing well.

However, the very thing that may have allowed women to participate in the writing of haiku, their aesthetic of the impersonal , also makes it hard to distinguish them from men. Japanese critics are fond of saying Basho’s haiku are like daimonds and Chiyo-ni’s are like pearls.

how terrifying

her rouged fingers

against the white chrysanthemums

woman’s desire

deeply rooted –

the wild violets

butterfly

you also get mad

some days [pp. 84-85]

The only woman in the Western tradition (to my knowledge) who wrote with any sort of sexual freedom (prior to the 20th century) wrote in ancient Greece – Sappho – born sometimes between 630 and 612 BC. Very little of her poetry remains, but her fame as a poet was and is well-recorded.

Of course I love you

but if you love me,

marry a young woman!

I couldn’t stand it

to live with a young

man, I being older.

One Girl

I

Like the sweet apple which reddens upon the topmost bough,

A-top on the topmost twig–which the pluckers forgot, somehow–

Forget it not, nay, but got it not, for none could get it till now.

II

Like the wild hyacinth flower which on the hills is found,

Which the passing feet of the shepherds for ever tear and wound,

Until the purple blossom is trodden in the ground.

And their feet move

And their feet move

rhythmically, as tender

feet of Cretan girls

danced once around an

altar of love, crushing

a circle in the soft smooth flowering grass

More of Sappho’s poetry can be found at Poemhunter.

Why did so few of Sappho’s poems survive? In a word: Christianity.

History tells us that Christians destroyed her poetry around 380 A.D., prompted by Pope Gregory Nazianzen. To be sure the job was done right, Pope Gregory VII organized another book burning in 1073 A.D.. The reasons for her poetry’s destruction haven’t survived, but it’s not hard to speculate. It was probably a combination of her perceived paganism and her open sexuality (as opposed to her reputed sexual orientation – which didn’t become an issue until much later).

There were other Hellenistic women poets and if you’re interested in pursuing the subject, a (fee based) article can be found at JSTOR: Hellenistic Women Poets.

The women of Rome lived in a more liberated time than the earlier Greek poets. However, the only woman whose poetry survives is Sulpicia. What little survives hints at a woman who, like Sappho, wrote freely about herself and her identity.

At last. It’s come. Love,

the kind that veiling

will give me reputation more

than showing my soul naked to someone.

I prayed to Aphrodite in Latin, in poems;

she brought him, snuggled him

into my bosom.

Venus has kept her promises:

let her tell the story of my happiness,

in case some woman will be said

not to have had her share.

I would not want to trust

anything to tablets, signed and sealed,

so no one reads me

before my love–

but indiscretion has its charms;

it’s boring

to fit one’s face to reputation.

May I be said to be

a worthy lover for a worthy love.

More of Sulpicia’s poetry can be found at Stoa.org.

After the fall of Rome and (probably not coincidentally) the rise of Christianity, women’s poetic voices are increasingly silent and silenced. It takes just over a thousand years before Marie de France appears – an Anglo-Norman poet. Project Gutenburg, increasingly my all-time favorite literary resource on the net, has made

the French Mediaeval Romances from the Lays of Marie de France by Marie de France available as a free E-Book. Don’t expect anything self-revelatory in Marie de France’s writing. Hers was a new age and a world apart. That is, the poets of Rome and Greece were long gone and unknown. Marie de France was writing in a tradition and convention defined by male poets. It would be another 700 years or so (18th and 19th century) before women began liberating themselves from the convention of the perfect woman – before they began writing about themselves, their lives and defining themselves.

During that time, the writings of Mary Sidney and Emilia Lanier (claimed to be Shakespeare’s Dark Lady by A.L. Rose) are relatively conventional. While Lanier’s Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum is rightfully called our first proto-feminist work, and while Lanier was the first woman in the English language to declare herself a poet, we get no sense of Lanier’s own identity through her poetry. The poem remains a conventionally literary (and characteristically Elizabethan) work that sets forth a forceful argument in defense of women. Of the women poets of the Elizabethan era, Lady Mary Wroth is, to me, the most compelling. You can find her works at Luminariam. The following sonnet, by Wroth, plays a curious game with prevailing Elizabethan gender roles. Many poems were written (Marlowe’s The Passionate Shepherd to his Love being the most famous) urging women to let down their guard. Wroth knows full well that she shouldn’t, assumes the role convention expects, but also, in the end, surrenders to the same “joyes” to which men are entitled.

Am I thus conquer’d? have I lost the powers,

….That to withstand which joyes to ruine me? *

….Must I bee still, while it my strength devoures,

….And captive leads me prisoner bound, unfree?

Love first shall leave men’s fant’sies to them free,

….Desire shall quench love’s flames, spring hate sweet showers,

….Love shall loose all his Darts, have sight, and see

….His shame and wishings, hinder happy houres.

Why should we not Love’s purblinde charmes resist?

….Must we be servile, doing what he list?

….No, seeke some host to harbour thee: I fly

Thy Babish tricks, and freedome doe professe;

….But O, my hurt makes my lost heart confesse:

….I love, and must; so farewell liberty.

* …have I lost the powers [to withstand that] which joyes to ruine me?

One senses a uniquely feminine perspective when reading Mary Wroth’s poems, but she still wrote firmly within expected conventions. And this is why Anne Bradstreet, writing about the same time, is such a rarity. While her initial poems are conventionally literary, her later, highly personal poems are a miracle. She is unique. Her few, later, personal poems assume a woman’s voice with as much passion as anything written by the ancient Greek and Roman poets.

My feeling is that women were defined (or trapped) by the convention of the perfect woman – asexual, virtuous, untouched and untouchable. Since I’ve always felt that the various arts share trends and attitudes (how can they not?) the depiction of the Angel, at least to me, parallels the expectation of women in art and society. After the  classical era of Roma and Greece in the West, and the Book of Poetry in the East, thousands of years ebbed and flowed before women were free to define themselves in their writings. Some might argue that they’re still constrained; but if so, those constraints have never been weaker.

classical era of Roma and Greece in the West, and the Book of Poetry in the East, thousands of years ebbed and flowed before women were free to define themselves in their writings. Some might argue that they’re still constrained; but if so, those constraints have never been weaker.

One last poet I haven’t mentioned (though there are, no doubt, others I’m unaware of): Al-Khansa (image at left) – an Islamic poet of the 7th century whose work was admired by Muhammad. Her poetry precedes Islam and is later influenced by it (through Muhammad himself). The poetry is beautiful but very different from a Sappho. The reader only very indirectly gets a sense of the poet’s personality and desires.

I look forward to ideas and recommendations from readers.

from up in Vermont

August 5, 2010