Reading poem 401 and Vendler’s three page, close reading provoked me to write another post. Vendler’s reading is one of those curious examples where she manages to go on at length without ever actually interpreting the poem. If the poem were a car, she would tell, through many attendant examples drawn from her voluminous literary knowledge, that the wheels were, in fact, round, that it had a steering wheel, headlights and brake lights, and then move on to the next automobile. Vendler writes at the outset: “To show, in verse, a soul passing through flame, and beyond it to the “White Heat” of incandescence, is a daunting undertaking.” To which I’d respond: “Yes, and?” And the “and” never shows up. Whenever Vendler gets into the etymology of words it’s usually a sign that she isn’t sure of what to say, so she’s going to throw glitter in the reader’s eye. It’s an impressive way to state the obvious. She’ll write of the final quatrain:

To compose an ending for her second, allegorical insight, Dickinson introduces three unexpected new insights. The first is that the Ores (with their initial admixture of dross) have been “impatient” to be purified. “Patient” comes from the Latin patior, to “suffer”; and in her use of “impatience,” Dickinson asserts that the Ores were not merely passively undergoing the Forge’s assaultive procedures, but rather longing for their completion.” [p. 182]

In other words, an incredibly long-winded and pedantic way of explaining that “impatient”, in case you didn’t know, means “impatient”. At any rate, she spends all three pages spinning words like this. The closest she comes to actually interpreting the poem (which she beautifully does in other poems) is in the final paragraph. She writes:

“Dickinson’s refashioning of the Christian narrative of God’s chastening purgation of the soul takes it into an entirely personal and secular sphere. Yet, paradoxically, the Bible remains the only location in which the poet can find sufficiently evocative symbols for her interior development.” [p. 183]

Yes, and? But that’s where Vendler leaves it. So let’s see if we can find out what Dickinson might have had in mind when writing the poem. What does she, possibly, mean?

Dare you see a Soul at the White Heat? Then crouch within the door — Red — is the Fire's common tint — But when the vivid Ore Has vanquished Flame's conditions, It quivers from the Forge Without a color, but the light Of unanointed Blaze. Least Village has its Blacksmith Whose Anvil's even ring Stands symbol for the finer Forge That soundless tugs — within — Refining these impatient Ores With Hammer, and with Blaze Until the Designated Light Repudiate the Forge —

As with other of her poems, this one has the feeling of defiance and argument, as though she were responding to (or feeling challenged by) something someone else has written or said. Nearly all of Shakespeare’s Sonnets have that feeling, as if between each of them there was a missing letter full of accusation and argument. To what might Dickinson have been responding?

My Dear Emily,

Honestly! Why do you persist in your determination to avoid Christian society? Some several weeks, I am sure, have passed since I or anyone have been so fortunate as to be graced by your presence! Surely tell us what keeps you so aloof? What ailment or, if not ailment, then what self-afflicted absorption so needlessly sequesters you? The Minister was in a White Heat this last Sunday! Why, you should have been there to see how he shook our little institution to the very foundations. You might have thought his words the hammer, the podium his anvil and we the ore set ablaze in the fine forge of our church. I do not think I overstate but that everyone set forth that day as fine a Christian as has ever been—our annointed souls ringing with the minister’s anvil. Why you insist on your vexatious and un-Christian quandaries will ever be a puzzlement to me.

Yours in Christ,

Victoria

To which Dickinson, much peeved, replied: “Dare you see a Soul at the White Heat?” You want to see a soul at white heat? I’ll show you a soul at white heat. From that furious question, beginning with “Dare” (in which I can’t help but hear—How dare you?), I read Dickinson’s poem as a defense of her isolation and life as a free-thinking poet.

Robert G. Ingersoll (1833–1899) was one of the more prominent freethinkers of his time. He was known as the “Great Agnostic”. Ingersoll, a lawyer, an orator and a Civil War veteran, is famous for his skeptical approaches to popular religious beliefs. He would speak in public about orthodox views and would often poke fun at them. Guests would pay $1 to hear him speak (equivalent to $30 in 2022).[4] Ingersoll was the leader of the American Secular Union, successor organization to the National Liberal League. [Wikipedia 10/14/23]

Then “crouch by the door”, she says. And that door I interpret as being to her bedroom (or writing room). She writes that red is the “common tint”. I read that as referring to the common Christian notion of purgation. By contrast, her own inspiration (heated in the forge of her imagination ) comes out of the forge without being colored by any dogma or theology. Her imagination and reasoning is “the light/Of unanointed Blaze”. I read ananointed as referring to her spiritual beliefs (reflected in her poetry) as being without the stamp of Christian theological approval.

Least Village has its Blacksmith Whose Anvil's even ring Stands symbol for the finer Forge That soundless tugs — within — Refining these impatient Ores With Hammer, and with Blaze

These lines I read as her equating the Blacksmith with the poet and free thinker—herself. The least village, she writes, has its poet whose anvil (the paper on which she writes) stands as a symbol for a “finer forge”—a rational spirituality rather than the ordinary color of Christian dogma. The poet’s pursuit of a spirituality founded in reason soundlessly tugs within, refining “these impatient Ores” (her spiritual quest for answers) with a poet’s “hammer” and “blaze” (pen and inspiration).

Until the Designated Light Repudiate the Forge —

Until the poem, which is the “Designated Light”, repudiates (transcends) the forge. In other words, DIckinson’s poetry makes real, makes manifest, the imagined and in doing so transcends what’s merely imagined within the forge and during the forging. The poem, by existing, repudiates the notion that her beliefs are purely imaginary. They are the real embodiment of her spirituality. These poems, in other words, are her bid for true immortality. They are her Designated Light. In some ways, in my opinion, this poem is possibly Dickinson’s most profound statement of her faith in her poetry—and her choice to write poetry.

Up in Vermont | October 14 2023

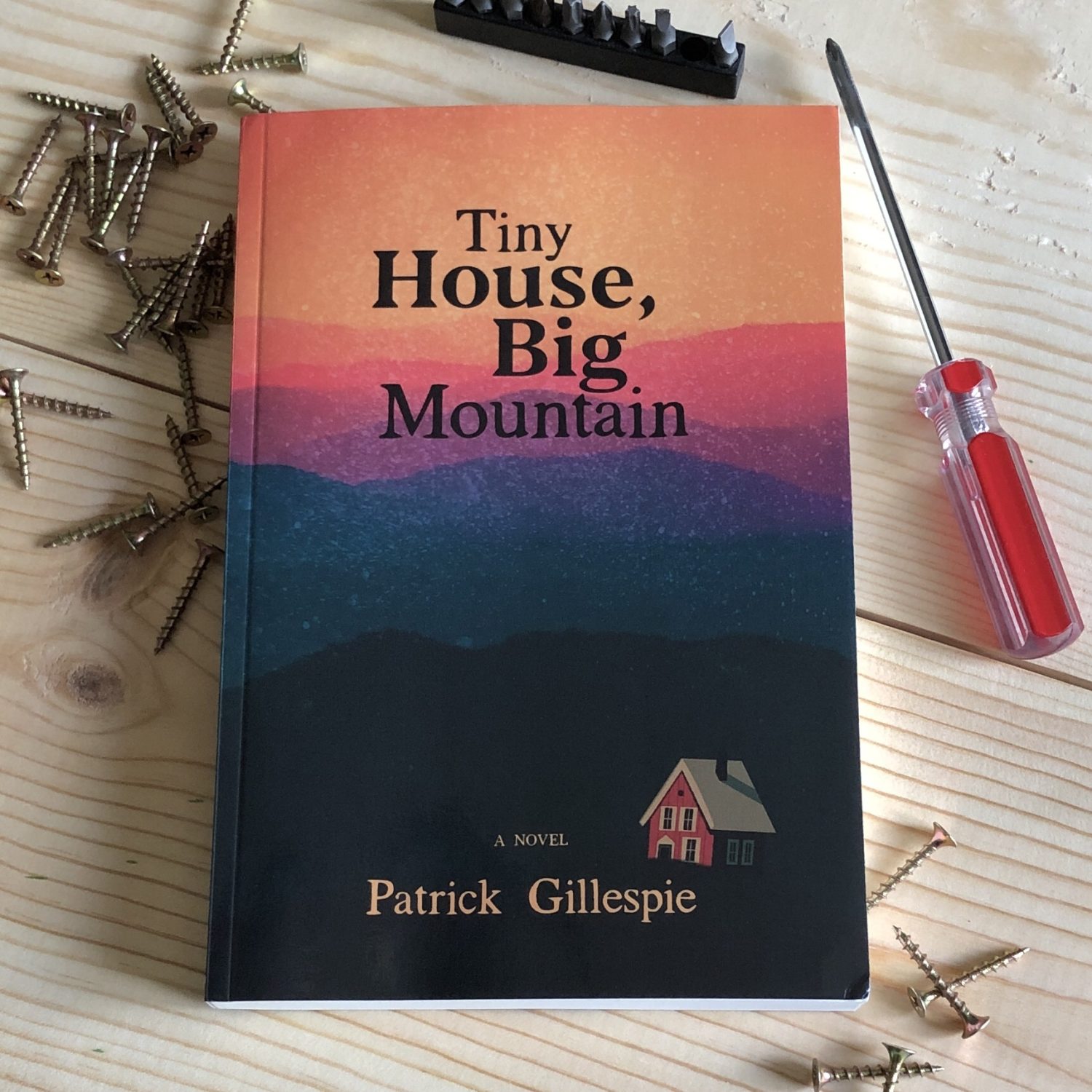

And I’m not just a blogger, but also a poet and novelist. Check out my first novel, published by Raw Earth Ink.