The oral tradition of Poetry

Poetry began as an oral tradition. Homer’s Odyssey is probably far older than Homer and Odysseus’ sojourn, in one form or another, may have been handed down for centuries from one storyteller to the next.

Each storyteller probably added details and expanded the story until, by the time Homer learned it, the epic was a real feat of memorization. As every reader of Mother Goose knows,  a ditty or poem that has a rhythm or rhyme is easier to remember than one that doesn’t.

a ditty or poem that has a rhythm or rhyme is easier to remember than one that doesn’t.

The Dactylic Hexameters of Homer’s Odyssey, it’s meter, was the rhythm that made the epic easier to remember. And a device used for the filling out of this meter was the Homeric Epithet. These colorful descriptions (or epithets) might have also served as cues – much like stage directions.

Before Homer, the tightly wound relationship between dance, music, rhythm and sound was demonstrated by recently discovered poems from ancient Egypt. In a book called The Ancient Egyptian Culture Revealed, Moustafa Gadalla writes:

The Egyptians perceived language and music as two sides of the same coin. Spoken, written, and musical composition follow the same exact patterns. Both poetry and singing followed similar rules for musical composition. Poetry is written not only with a rhyme scheme, but also with a recurring pattern of accented and unaccented syllables. Each syllable alternates between accented and unaccented, making a double/quadruple meter and several other varieties. Patterns of set rhythms or lengths of phrases of Ancient Egyptian poems, praises, hymns, and songs of all kinds, which are known to have been changed or performed with some musical accompaniment, were rhythmic with uniform meters and a structured rhyme. ¶ Ancient Egyptian texts show that Egyptians spoke and sang in musical patterns on all occasions and for all purposes–from the most sacred to the most mundane. [p. 155]

This oral tradition continued with the very first works of the Anglo Saxons, the alliteration of Beowulf, up until the start of the 20th Century, when poets like Frost, Cummings, and Yeats, continued to imbue their poetry with the sounds and rhythms of its oral, musical, lyrical and storytelling ancestry.In short, traditional poetry finds its roots in music.

Free Verse is a different Genre

This all ended with the 20th Century. The poetry of meter & rhyme, the techniques formed out of an oral past, had become dogmatic and stylized. A new genre replaced the poetry that had been written for thousands of years – free verse.

Though it may seem controversial to suggest that free verse is a new genre (only tangentially related to the poetry of the previous 200o years), the assertion isn’t to the detriment of free verse. Free verse practitioners have themselves, to varying degrees, deliberately avoided the traditional rhythms of a regular meter; have eschewed rhyme; have avoided alliteration; and whole schools have rejected techniques like metaphor. All of these techniques gre w out of an oral tradition – frequently, or so scholars think, as mnemonic aids or for the purposes of musical accompaniment.

w out of an oral tradition – frequently, or so scholars think, as mnemonic aids or for the purposes of musical accompaniment.

Free verse is the child of the 20th Century printing press (which isn’t to say that free verse can’t be read aloud and enjoyed as such). And it’s not to say that free verse doesn’t borrow techniques from the oral tradition, but free verse doesn’t do so systemically. (Poets, like William Carlos Williams, studiously avoided anything short of what he considered plain speech or plain English and the avant-garde is premised on the avoidance of anything that smacks of traditional poetry.) It was the explosive availability of the printed word that made the visual cues of free verse possible. Aurally, there is frequently nothing that distinguishes free verse from prose. Cleave Poetry, for example, is defined by its visual appearance (rather than any aural cues).

In short, free verse didn’t evolve from the poetry of the oral tradition, it replaced it.

So what does this all have to with meter and rhyme? Just this. The near total dominance of free verse in print media and on store shelves (stores that bother with a significant collection) has left its mark on what readers consider a modern style. It makes writing meter and rhyme much more challenging but also more rewarding if done well.

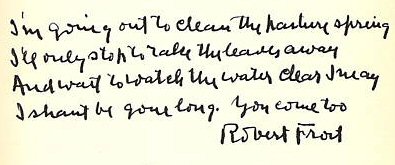

Unlike metrical poetry prior to the 20th Century, the best modern metrical poetry does not draw attention to itself. The best metrical and rhyming poems make the reader feel as though they are reading modern English (without also feeling like free verse). The demands weed the men from the boys, the girls from the women. Robert Frost was a master of this illusion and so was Yeats and Stevens.

Grammatical Inversions & Rhyming: Subject • Verb • Object

When novice poets try to write meter, they frequently use what are called grammatical inversions. They can be effective or they can sound contrived but I suspect that few poets really understand the origin of these techniques, how they’ve  been used, and why.

been used, and why.

The best book on the subject is by John Porter Houston. If you’re a poet and you’re interested in this tradition as practiced by our greatest poet, then this is the book to read. I had a hard time finding it at Amazon but when I finally did I scanned in my own book for their image and added a short review. Here’s how Houston introduces the book.

The history of SOV word order (as, using a common abbreviation, I shall henceforth call the subject•direct object•verb pattern) vanishes into the Indo-European mists, which has encouraged linguists to formulate various theories of its original importance or even of its former dominance. Be that as it may, the word order shows up historically in Greek, Latain, and Germanic, being associated in the latter especially with subordinate clauses. However, it seems unlikely that, in its English poetic form, SOV is so much an atavistic harkening back to primeval roots as it is a consequence of the adaptation to English of the Romance system of Riming verse. Verbs in Old French and Italian make handy rimes, and they make even better ones in English because so many English verbs are monosyllabic. The verse line or couplet containing a subject near the beginning and a verb at the end is a natural development. [p. 2]

The English language, descended from the Germanic languages, prefers the following pattern:

Subject | Verb | Object (SVO)

Subject | Verb | Object

The girls | play | on the seesaw.

But poets, as Houston observed, found it convenient, for the sake of rhyme, to invert the grammar. They might write:

The girls on the seesaw play:

“Life goes up, life goes down

“You’ll have good luck another day!”

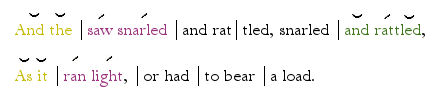

The first line would be an SOV construction:

Subject | Object | Verb

The girls |on the seesaw |play

This is a construction one sees very often among amateur poets writing rhyme. The only purpose for the grammatical inversion is to make the rhyme. It’s what free verse poets (more so than others I think) derisively call rhyme driven poetry. And it’s precisely this sort of writing that was acceptable right up until the start of the 20th century.

With this in mind, a somewhat peculiar commentary on rhyme driven poetry can be found at the Poetry Foundation’s blog Harriet. The post is by Alicia Stallings.  The reason I say it’s peculiar is because, though she expresses exasperation at the criticism, she never offers an alternative. She begins her post by writing:

The reason I say it’s peculiar is because, though she expresses exasperation at the criticism, she never offers an alternative. She begins her post by writing:

As a poet who works in form, I weary of seeing in critiques–either in on-line workshops or in published reviews–the complaint that a poem or phrase or line is “rhyme driven”. Of course rhyming poetry is rhyme driven. Rhyme is an engine of syntax.

But then Stallings immediately acknowledges what the criticism really means: that is, when it “is obvious [that] the whole purpose of the line is to arrive at some obvious predestined chime, like the set-up of a punch line.” Stallings then offers some examples of why a poem might feel rhyme-driven, but she never offers a reason why the criticism shouldn’t be made. However, she does write:

But it seems to have become an immediate and unthinking response to lines that rhyme that are in any way out of the ordinary–particularly anything that has the slightest whiff of “inversion”–that is, out of “natural” English word order–which is often interpreted as the blandest, strictest of simple declarative sentences.

And this is to say that such criticism can be carried too far; but then inasmuch as any criticism can be carried too far, this doesn’t invalidate the original impulse. The bottom line is this: Stallings makes sure her rhymes don’t arrive like some “obvious predestined chime”. Rhyme might be the engine, but she makes sure (in her own poetry) that the engine isn’t heard. She’s an exceedingly skillful rhymer. So, the best advice, as regards Stallings, is to do as she does. Read her poetry. Make your rhymes feel accidental, as if they’re an inevitable accident of subject matter.

Robert Frost, on these very grounds, was deservedly proud of his poem “Stopping by Woods”.

Perhaps because of these efforts, and on at least one occasion – his last appearance in 1962 at the Ford Forum in Boston- he told his audience that the thing which had given him most pleasure in composing the poem was the effortless sound of that couplet about the horse and what it does when stopped by the woods: “He gives the harness bells a shake/ To ask if there is some mistake.” [Pritchard, Robert Frost: A Literary Life Reconsidered p. 164]

If you want a model for how to rhyme, read Frost’s Stopping by Woods or The Road not Taken again and again. No one would accuse these poems of feeling rhyme driven although, as Stallings would point out, that’s precisely what they are – rhyme driven.

Again (and I don’t think beginning poets appreciate this enough) it’s not whether a poem is rhyme-driven, it’s whether it feels and reads rhyme driven. Are the rhymes determining the line and the subject matter, or is the subject matter determining the rhymes? In Frost’s poems, it’s hard to imagine how they could have been written any other way. The rhymes feel entirely accidental. The rhymes feel driven by the subject matter; and this is the effect you are looking for.

For the record, I love the SOV construction – especially when done well. I don’t think I’ve ever used the syntax in my own poetry but I might, just for the enjoyment.

Shakespeare’s use of SOV wasn’t for the sake of a rhyme. Shakespeare used the reversal of normal English (unusual even in Shakespeare’s day) to add metrical emphasis and elegance; to make a line more memorable; to add meaning; or to reveal character.

Here, for instance, is how Shakespeare reverses the normal syntax of English to convey and build suspense. Horatio is describing having seen the ghost of Hamlet’s father (I have included Houston’s explanatory comment):

thrice he walk’d

thrice he walk’d

By their oppresss’d and fear-surprised eyes

Within his truncheon’s length, whilst they, distill’d

Almost to jelly with the act of fear,

Stand dumb and speak not to him. This to me

In dreadful secrecy impart they did,

And I wish them the third night kept the watch,

Where, as they had deliver’d, both in time,

Form of the thing, each word made true and good,

The apparition comes. (Hamlet I, ii, 202-11)

Having devised a sentence in more or less normal word order in which the verbs have radically different positions, Shakespeare then resorts to inversion, and the OVSV clause contains, moreover, a peculiar reversal of impart and did. The next sentence places two circumstantial expressions between subject and verb, so that the latter, with its short object, seems curiously postponed, even though the number of intervening syllables is not great. Finally, in the concluding subordinate clause, both subject and verb are held off until the end. [p. 83]

Notice how Shakespeare holds off the apparition comes until the end of the line. Throughout the passage the inverted grammar underpins the feeling of terror and suspense, the feeling of a character whose own thoughts are disrupted and disturbed. (I think it’s worth commenting at this point, especially for readers new to Shakespeare, that this is poetry. Elizabethans did not talk like this. They spoke an English grammar more or less like ours. Shakespeare can be hard to read because he is a poet, not because he is Elizabethan.)

- The tradition of altering grammar and syntax for the purposes of making language more memorable is a lovely one.

- The tradition of altering grammar and syntax for the sake of rhyme is dubious.

Toward the end of the Houston’s introduction, he makes an interesting point. Although the use of the SOV construction continued into the 19th century (even with a poet like Keats who was consciously trying to shed the feeling of antiquated and archaic conventions), the general trend was toward a more natural speech. Houston writes:

The importance of SOV word order in subsequent English blank verse is worth noting. Although it is scarcely unexpected that Milton, with his latinizing tendencies, liked the device,its persistence in the romantics can be a trifle surprising. Keats slight use of SOV in The Fall of Hyperion is odd, given that there he supposedly tried to eliminate the Miltonisms of Hyperion to some extent; Hyperion, in fact, contains no SOVs. An example of two in Prometheus Unbound does not seem incongruous with the rest of the language, but finding SOV word order in The Prelude runs somewhat counter to our expectations of Wordsworth’s language.

but scarcely Spenser’s self

Could have more tranquil visions in his youth,

Or could more bright appearances create

Of human forms (VI, 89-92)

Examples are to be found in The Idylls of the King and seem almost inevitable by the stylistic conventions of the work, but the use of SOV in the nineteenth century is essentially sporadic, if interesting to observe because of the strong hold of tradition in English poetry. [p. 3-4]

The usage was ebbing. The result is that its use in rhyming poetry stood out (and stands out) all the more. And now, when the conventional stylistic aesthetic is that of free verse, SVO inversions stands out like a sore thumb.

Anyway, this short passage can’t possibly do justice to the rich tradition of grammatical inversion in English Poetry. Reading Houston’s book, if you’re interested, is a better start. The point of this post is to raise poets’ awareness of why they might be tempted to write like this; and to make them aware of what they’re hearing when they read poetry prior to the 20th century.

Other grammatical Inversions

There are other types of inversions besides Subject•Verb•Object . In a recent poem I examined by Sophie Jewett, you will find the following line:

I speak your name in alien ways, while yet

November smiles from under lashes wet.

The formulation lashes wet reverses the order of adjective and noun for the sake of rhyme. This sort of inversion is also common among inexperienced poets.

Conveniently moving around parts of speech might have been acceptable in the Victorian era and before, but not now.

And here’s another form of grammatical inversion by Thomas Hardy from The Moth-Signal:

“What are you still, still thinking,”

“What are you still, still thinking,”

He asked in vague surmise,

That you stare at the wick unblinking

With those deep lost luminous eyes?”

Normally the present participal, unblinking, would follow the verb stare. This is the way grammar works in normal English sentences. However, for the sake of the rhyme, Hardy reversed the direct object, at the wick, with the past participal unblinking. The effect is curious. To what is unblinking referring? – one might ask. Is it the stare that is unblinking? – or the wick? Apologists meaning to rationalize this inversion might point out that the syntactic ambiguity is brilliantly deliberate. I don’t buy it; but they could be right.

- Again, my advice would be to tread lightly with this sort of inversion. It smacks of expediency.

As I find other examples I will post them.

Ultimately, one of the most telling attributes of an experienced rhymer is the parts of speech he or she chooses to rhyme. A novice may primarily rhyme verbs or nouns. The novice’s rhymes will be end-stopped. In other words, the line and sentence will end with the rhyme. The rhymes of the more experienced poet will move like a snake through his verse. The rhymes will shift from verb, to noun, to adjective, to preposition, etc. They will fall unpredictably within the line’s syntax and meaning – as if they were an accident of thought.

In the spirit of put up or shut up, check out my poem All my Telling. Decide for yourself whether I practice what I preach. And here is Alicia Stallings what what is, perhaps, the most succinct advice on rhyme that I have ever read – her Presto Manifesto. The most important statement from her manifesto, to me, is the following:

There are no tired rhymes. There are no forbidden rhymes. Rhymes are not predictable unless lines are. Death and breath, womb and tomb, love and of, moon, June, spoon, all still have great poems ahead of them.

You will frequently hear poets and critics remark that a given rhyme is tired or worn. As a counterexample they will themselves offer poems with rhymes that, to my ear, sound concocted and contrived. I call this sort of thing safari-rhyming – as if the poets had gone safari hunting, shot the rare rhyme, and proudly mounted it. The truth of the matter is this: the English vocabulary is finite. There are only so many rhymes. It’s not the rhymes themselves that are worn or trite, but the lines that are tired. Give an old rhyme a new context and magic happens. Robert Frost’s rhymes in Stopping by Woods are nothing if not tired; but the poem’s effortless progression of thought and idea means we don’t notice them. They become a kind of music rather than a distraction.

And this is what rhymes are meant to do. Ideally, they’re not meant to be noticed. This is why the novel rhyme can be as distracting as the line that is syntactically contorted for the sake of a rhyme. The best rhymes are like a subtle music. If, when reading a rhyming poem aloud, the listener doesn’t immediately discern the rhymes, take that as a good sign.

One last thought on rhymes from Stallings:

Translators who translate poems that rhyme into poems that don’t rhyme solely because they claim keeping the rhyme is impossible without doing violence to the poem have done violence to the poem. They are also lazy.

I agree.

On Keeping the Meter

This is the most difficult portion of the post to write because so much of what I write will be construed as a matter of taste; and the distinctions between mediocre meter and meter written well can be subtle. Readers will have to decide for themselves. Way back when, I wrote a post called Megan Grumbling and the Modern Formalists. The point of the post was to demonstrate how the stylistic conventions of free verse had influenced, adversely, the meter and blank verse of modern formalists. (This would seem to go against my earlier statement that poets writing meter can’t write the same way (as in the 19th century) since the advent of free verse. Not entirely. As with anything, there’s a balance to be struck. The best meter doesn’t draw attention to itself.) Feel free to read the whole post, but I’ll extract the most relevant part because I think it has some bearing on this post.

In the January 2006 issue of POETRY magazine, we find some beautiful poems by Megan Grumbling. But remember, this is mirror mirror world. Just as Dryden’s heroic couplets showed up, ghostlike, in his blank verse, free verse asserts itself, ghostlike, in modern formal verse.

“Their strident hold upon the back roads pulls

our morning drive, out to where Oak Woods Road

crosses the river that they call Great Woks.

The nearby fields so rich it’s hard to breathe–

the hay treacly with auburn, grasses bronzed–

we stop before a red farmhouse, just shy

of where the river runs, where maple trees

have laid the front lawns ravished with their loss.”

The enjambment of the first three lines has all the flavor of free-verse. There are no auditory clues (in the way of syntactical units) that might hint to a listener that these are lines of blank verse. One might as easily write the first sentence as follows:

Their strident hold upon the back roads pulls our morning drive, out to where Oak Woods Road crosses the river that they call Great Woks.

The average reader would never suspect that this was blank verse. The reader might, in a moment of preternatural attentiveness, notice that the line is entirely iambic. That said, there is no indication that this sentence is Iambic Pentameter. Given Grumbling’s approach, one might as easily print her poem as follows:

Their stri|dent hold |upon |the back

roads pulls |our mor|ning drive, |out to

where Oak |Woods Road |crosses |the river

they call |Great Woks. |The near|by fields

so rich |it’s hard |to breathe– |the hay

treacly |with au|burn, grass|es bronzed–

we stop |before |a red |farmhouse,

just shy |of where |the ri|ver runs,

where ma|ple trees |have laid |the front

lawns ra|vished with |their loss.

This is perfectly acceptable iambic tetrameter, but for the short last line. I only had to remove the purely metric “that”. It might be argued that one could submit any iambic pentameter poem to the same exercise, but such an argument would only be partially true. One would find it exceedingly difficult to apply the same exercise to Shakespeare’s passage from Antony and Cleopatra. Or, more fairly, consider Frost’s An Encounter (more fairly because Grumbling’s poetry is clearly inspired by Frost.)

Once on the kind of day called “weather breeder,”

When the heat slowly hazes and the sun

By its own power seems to be undone,

I was half boring through, half climbing through

A swamp of cedar. Choked with oil of cedar

And scurf of plants, and weary and over-heated,

And sorry I ever left the road I knew,

I paused and rested on a sort of hook

That had me by the coat as good as seated…

And now for the tetrameter version:

Once on |the kind |of day |called “weather

breeder,” |When the |heat slow|ly hazes

and the |sun by |its own |power seems

to be |undone, |I was |half boring

through, half |climbing |through a swamp

of ce|dar. Choked |with oil |of cedar

And scurf |of plants, |and wear|y and

over-|heated, |And sor|ry I

ever |left the |road I |knew, I

paused and |rested |on a sort |of hook

That had |me by |the coat |as good

as seat|ed…

The latter isn’t a very passable version of iambic tatrameter. The third line is entirely trochaic and can only be “rescued” if we elide power to read pow’r or read the line as follows:

and the |sun by |its own pow|er seems

Though this too is unsatisfactory. The fifth line fails altogether. I picked Frost’s poem at random (lest the reader think I picked one poem especially antithetical to such treatment). What the poem illustrates is Frost’s skillful wedding of sense (grammatical & otherwise) to blank verse – Iambic Pentameter.

The same commitment is not sensed in Grumbling’s poem, skillful though it is. One might assert that Grumbling’s poem is primarily iambic and only secondarily pentameter. The ghostly influence of free-verse pervades her poem, just as the ghost of heroic couplets pervaded Dryden’s blank verse. One might say that she only grasps the surface of blank verse. But her choices might also be deliberate.

This is actually a good exercise.

If you can successfully convert your Iambic Pentameter to Iambic Tetrameter or even Iambic Trimeter, then you’re probably doing something wrong. If nothing else, your meter may be too regular or the joining of line and thought may be too slack. There’s an art to fitting thought, meaning and syntax to a metrical line. It’s subtle and difficult to describe but, if done well, line and meter are like hand in glove.

Not to pick on Timothy Steele but… Steele illustrates the opposite dilemma. There’s a stiffness to his meter that one can learn from. His poem, Sweet Peas, starts us off:

The season for sweet peas had long since passed,

And the white wall was bare where they’d been massed;

Yet when that night our neighbor phoned to say

That she had watched them from her bed that day,

I didn’t contradict her…

In particular, compare the following:

Yet when that night our neighbor phoned to say

Then one foggy Christmas Eve/ Santa came to say:

(The latter line is from the Christmas Carol Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer) The point of the comparison, cruel though it may be, is to demonstrate what they both have in common – a slavish devotion to an Iambic beat. In the case of the Christmas Carol, it’s necessary. The lyrics, after all, have to coincide with the rhythm of the carol. (You can’t have variant beats in Christmas Carols.) Steele doesn’t have that excuse. His line is full of metrical expediencies.

Normally, the average English speaker would say:

“Yet our neighbor phoned that night saying she had watched them…”

But that’s not Iambic Pentameter. Steele had to move things around. The first thing he does is to shift “that night”. That’s not ideal, but there’s some justification for it. Maybe he wants to emphasize that night? Curiously though, he doesn’t punctuate the clause – Yet when, that night, our neighbor phoned… One would think, if emphasis were the motive, he would want to add some punctuation. As it is, the odd placement has the feel of a metrical expediency. But the phrase phoned to say only makes it worse. The phrase is modern English but in this context it sounds entirely expedient, not just metrically but because it’s clearly thrust to the line’s end for the sake of a rhyme. (This is a rhyme driven line.)

The line is just too obviously metrical.

Three of the four lines are end-stopped, negatively emphasizing the rhyme and meter. The third line is marginally end-stopped. All this combined with the fact there’s only two variant feet out of the first 20 makes for some very wooden meter.

Here’s the rest of that opening verse from Steele’s poem:

The season for sweet peas had long since passed,

The season for sweet peas had long since passed,

And the |white wall| was bare where they’d been massed;

Yet when that night our neighbor phoned to say

That she had watched them from her bed that day,

I didn’t contradict her: it was plain

She struggled with the tumor in her brain

And, though confused and dying, wished to own

How much she’d liked the flowers I had grown;

And when she said, in bidding me good night,

She thought their colors now were at their height–

Indeed, they ne|ver had |looked lovelier–

The only kind response was to concur.

These lines are an object lesson in how not to write meter and rhyme. There are only three variant feet out of 60. All but one of the lines are strongly end-stopped. Steele’s use of contractions is a matter of expediency. For instance, in line 8, he contract’s she’d but doesn’t contract I had. It feels arbitrary. The effect is to highlight the obviousness of the metrical beat. The rhymes are mostly nominal or verbal and, because the lines are end-stopped, they land with hard thumps. A poet might be able to get away with any one of these features in isolation, but when thrown together, the poetry feels contrived. Just as an experiment, let’s see if we can turn this poem into an Iambic Tetrameter.

The season for sweet peas had long

Since passed, and the white wall was bare

Where they’d been massed; yet when that night

Our neighbor phoned to say that she

Had watched them from her bed that day,

I didn’t contradict her: it

Was plain she struggled with the tumor

In her brain and, though confused

And dying, wished to own how much

She’d liked the flowers I had grown;

And when she said, in bidding me

Good night, she thought their colors now

Were at their height– indeed, they never

Looked lovelier– the only kind

Response was to concur.

What do you think? I actually think it improves the poem. I only had to remove one word. The lines take on a certain sinuousness and flexibility that moderately makes up for their thumping iambics and subdues the cymbal crash of their end-stopped rhymes. They become internal rhymes – they are registered but no longer hit the reader over the head.

If you’re having trouble writing meter that isn’t end stopped (and if you’re not rhyming), remove two words from your first line and shift the rest accordingly. (And you can try removing other metrically expedient words along the way to really shake things up.) I’ll demonstrate. Rather than pick on any more modern poets, here’s something from the first act of Gorboduc, the first English drama written in blank verse (and just as end-stopped and metrically conservative as some modern formalist poetry):

There resteth all, but if they fail thereof,

And if the end bring forth an evil success

On them and theirs the mischief shall befall,

And so I pray the Gods requite it them,

And so they will, for so is wont to be

When Lords and trusted Rulers under kings

To please the present fancy of the Prince,

With wrong transpose the course of governance

Murders, mischief, or civil sword at length,

Or mutual treason, or a just revenge,

When right succeeding Line returns again

By Jove’s just Judgment and deserved wrath

Brings them to civil and reproachful death,

And roots their names and kindred’s from the earth.

So, let’s remove the word thereof, which is only there for the sake of meter (a metrical filler):

There resteth all, but if they fail, and if

The end bring forth an evil success on them

And theirs the mischief shall befall, and so

I pray the Gods requite it them, they will,

for so is wont to be when Lords and Rulers

To please the present fancy of the Prince,

With wrong transpose the course of governance

Murders, mischief, or civil sword at length,

Or mutual treason, or revenge, when right

Succeeding Line returns again by Jove’s

Just Judgment and deservèd wrath brings them

To civil and reproachful death, and roots

Their names and kindred’s from the earth.(…)

Voila! What do you think? The lines take on greater flexibility and there are fewer end-stopped lines. Even though the overall pattern is just as relentlessly iambic, the effect is somewhat mitigated by the shift between line and thought. You can practice the same with your own poetry, even if its rhymed. You could even try writing Iambic Hexameter, then shifting all the lines so that they’re Iambic Pentameter.

Metrical Fillers

This, as it turns out, is the most contentious part.

I’m fairly hard-nosed about what are (in my view) egregious metrical fillers, but many formalist poets are equally pugnacious in protecting their turf.

The word at the top of my list is upon. While, no doubt, the words has its place, my irritation stems from its reflexive use as an all too convenient iambic substitute for on. Most formalist poets use it. They’re not apologetic. And I’m not apologetic when I call it lazy. The problem, in many cases, is that poets (even free-verse poets) misuse the word. Upon is not universally interchangeable with on. Also, my sense is that, in terms of everyday speech, on has more or less replaced upon. Upon has become a primarily literary usage and feels fusty to me.

But that’s only my opinion.

And it’s easy to get hung up on the word. The point is to avoid metrical fillers – words that are unnecessary to the sense of a line’s meaning (whose only purpose is to fill the meter). Here’s a sample I discussed in my earlier post on Megan Grumbling:

we skim as much brimmed crimson as these few

stout bags will hold within, enough to lay

four inches of the fall upon this field.

The word upon expediently substitutes for on. The word “within” is metrical padding. How else does a bag hold anything but “within”?

Later in Grumbling’s poem, more metrical padding appears with “out to where the Oak Woods Road…” Using modern English, we say: “out where the Oak Woods Road…” A.E. Stallings indulges in the same sort of metrical expediency.

Sing before the king and queen,

Make the grave to grieve,

Till Persophone weeps kerosene

And wipes it on her sleeve. [Song for the Women Poets]

The added and unnecessary preposition (to) before (grieve) is nothing more than metrical filling. Here is another example from Stallings‘ The Dollhouse:

And later where my sister and I made

The towering grown-up hours to smile and pass:

Again, the effect is antiquated. The preposition (to) before (smile) is unnecessary – another metrical filler.

However, some of the most abused metrical fillers are adjectives, especially among poets first tackling meter. My advice to poets just starting out is to write meter without adjectives or write with a strict limit (maybe one for every ten lines). Whether writing meter or free verse, nothing can weaken a line like an adjective. Use them sparingly.

After so many examples of what not to do, I thought I’d close with a fine example of beautifully modulated meter and rhyme by Annie Finch (whose book I will be reviewing soon):

Do you | hear me, |Lycius? |Do you hear |these dreams

Do you | hear me, |Lycius? |Do you hear |these dreams

moving |like words |out of |the air, it seems?

You think you saw me thin into a ghost,

impaled |by his |old eyes, with |their shuddering boast

of pride |that kills |truth with | philosophy.

But you hear |this voice. It is a serpent’s, or

is it |a wom|an’s, this rich |emblazoned core

reaching |out loud for you, as I once reached

for you with clinging hands, and held you, and beseeched. (…)

These are the opening lines to Lamia to Lycius, from Annie Finch’s new book Calendars. The poem is written in open heroic couplets, like Steele’s, but the difference is night and day. The thing to notice is that there are only two end-stopped lines in these first nine. The syntax and thought of the lines moves sinuously through the line ends, subduing the rhymes. The effect is to make the rhymes feel more organic, more like an outgrowth of the poem’s subject matter. Notice also the rich use of variant feet balanced against more regular iambic feet and lines. (I’ve marked phyrric feet in grey.) Notice also the absence of metrical fillers. Finch isn’t determined to keep a strict count like other poets – Timothy Steele or Dana Gioia (the link is to my review of his poetry). The result is a far more varied and rich voice.

If this post has been helpful, let me know.