This was a Poet —

It is That

Distills amazing sense

From ordinary Meanings —

And Attar so immense

From the familiar species

That perished by the Door —

We wonder it was not Ourselves

Arrested it — before —

Of Pictures, the Discloser —

The Poet — it is He —

Entitles Us — by Contrast —

To ceaseless Poverty —

Of portion — so unconscious —

The Robbing — could not harm —

Himself — to Him — a Fortune —

Exterior — to Time —

[FR 446/J448]

So. I’ve read a second interpretation of this poem, now by Cristanne Miller (the first by Helen Vendler) and both interpretations seem to fudge the final quatrain. Both seem to muddle. The reasons for the confusion, as with many of Dickinson’s more abstruse poems, are the “nonrecoverable deletions” (as Cristanne Miller nicely describes them). Essentially, because of the constraints of form, Dickinson chooses to delete connectives and syntax that would guide a reader’s understanding.

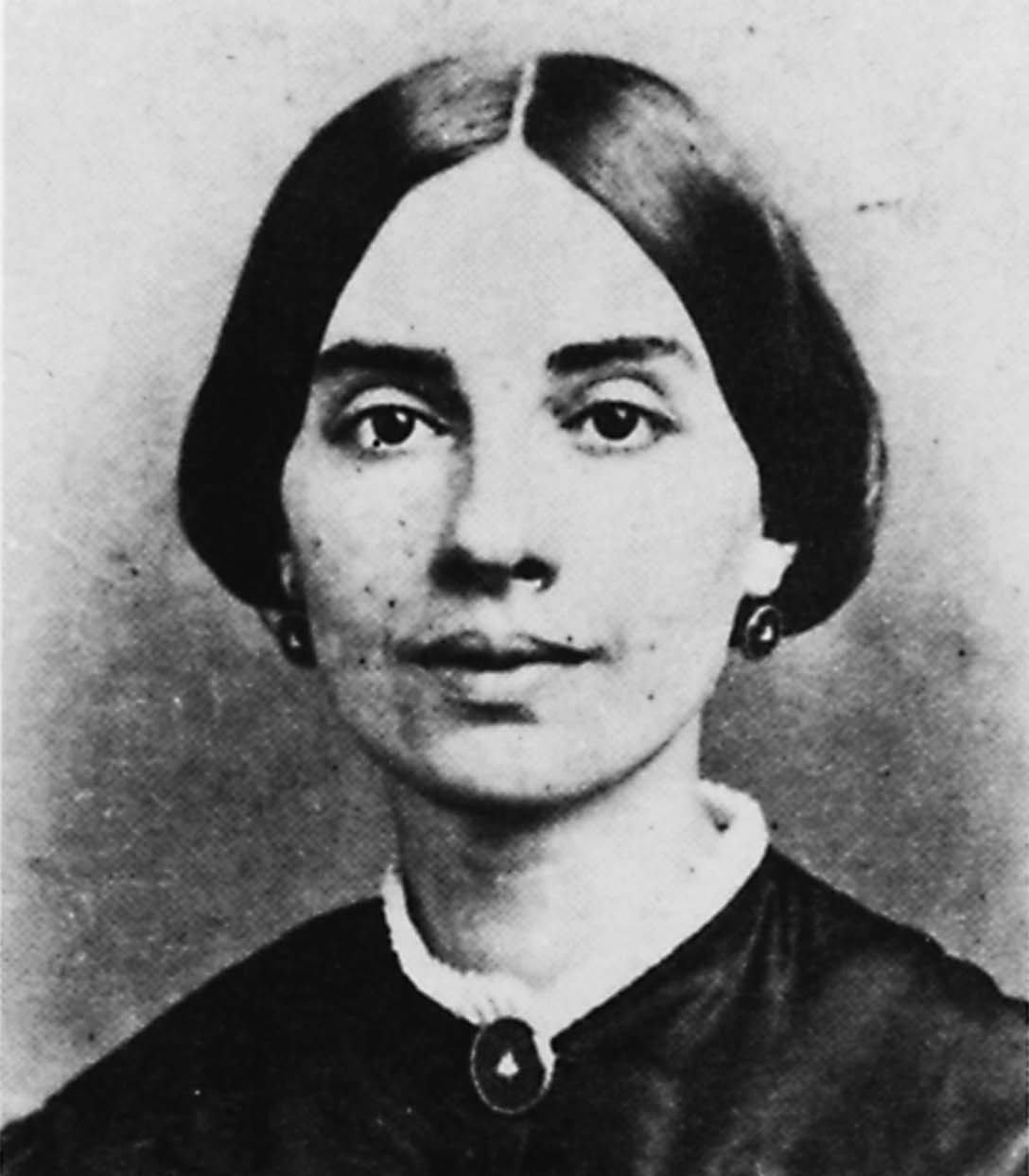

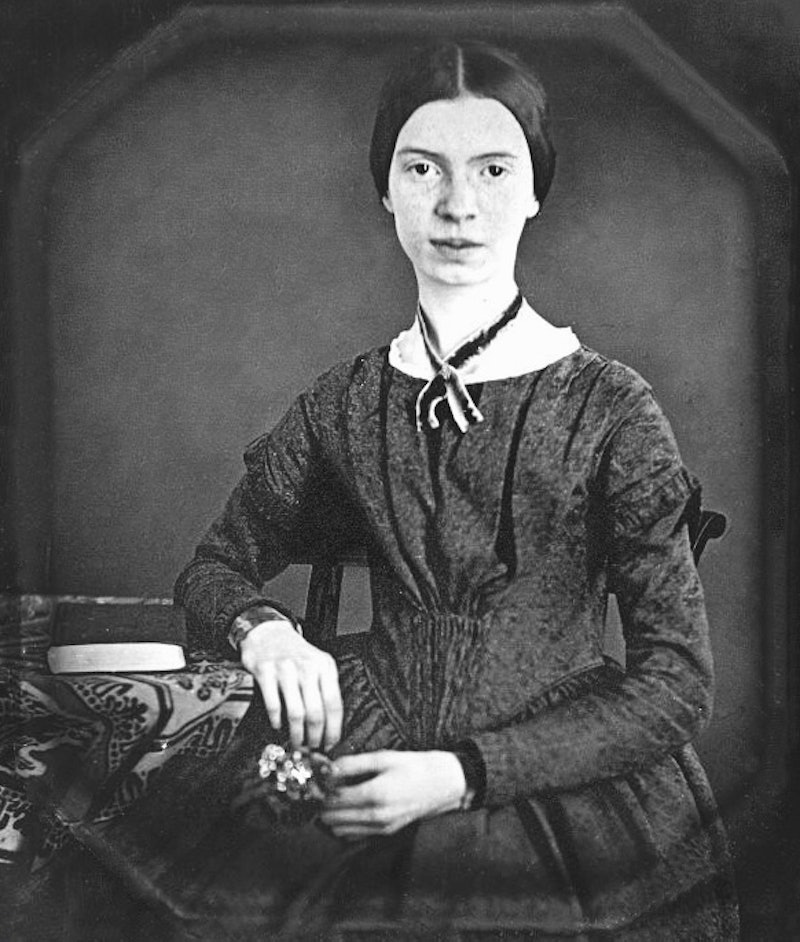

- Aside: I know it’s peak heresy to ask this question, but I do wonder to what degree Dickinson was aware of her poetry’s frequent obscurity. I’ll make the baseline assumption that her poems made perfect sense to her. If you had asked her what she meant by the final quatrain of This was a Poet, she might have looked at you like you were daft. (She didn’t take well to Higginson’s critiques and he learned—quickly—not to offer them.) And that makes me wonder if anyone ever asked her for clarification? She did send many of her poems to friends and relations, especially Susan Huntington Gilbert Dickinson. Based on my own lifelong experience as a poet, I’m going to say, No. On the other hand, maybe they didn’t need clarification? They were living in the same town, the same culture, spoke over tea and exchanged letters. We might expect a reader like Susan to fill in the blanks. So the question is this: Was Dickinson knowingly obscure or was she too familiar with her own poetry to recognize its obscurity? To say that she was knowingly obscure strikes me as out and out anachronistic. Poets in the mid 19th century were writing to be understood. Full stop. The 20th century’s infatuation with “pointless obscurity”, as William Logan nicely put it, just wasn’t a thing when Dickinson was writing. Does that mean that Dickinson was too familiar with her own poetry? There’s probably an element of truth to that. Another way of putting is that she might have expected too much from readers other than friends and family. Her syntactic compression/ellipsis/metonymy is part and parcel of her poetic art, but that’s a fine line. I wouldn’t have her poetry any other way, but sometimes, we must admit that her meaning is every reader’s best guess.

This was a Poet —

It is That [poetry]

Distills amazing sense

From ordinary Meanings —

And Attar so immense

My impression is that most readers interpret That as referring to the Poet. This would be Miller’s interpretation and, unless I’m mistaken, Vendler’s. I actually read That as referring not to the poet but to poetry in general. Normally this would be a four line stanza. R.W. Franklin notes that these lines are made four lines in “derivative collections” and Miller prints the poem this way (in her book A Poet’s Grammar). This makes the first line read: This was a Poet — It is That. Printing the poem this way makes it more tempting to associate That with the Poet. But if we print it according to Dickinson’s own lineation, then the assertion This was a Poet stands by itself. The statement is in the past tense and I read it, in a sense, as an epitaph. I read the poem as like a scene in a play. We’re accompanying Dickinson (or the speaker) on a nice afternoon’s walk through the graveyard (actually a thing in Victorian times). As we accompany Dickinson, she pauses at a grave stone we might have overlooked. She says,”This was a Poet.” Recognizing the poet’s grave, she then is reminded of his poetry and says, almost to herself, “It is That, that distills amazing sense from Ordinary meanings”. In her book “Emily Dickinson’s Poems: As She Preserved Them”, Miller notes that in his “Letter to a Young Contributor”, Higginson wrote, “Literature is attar of roses, one distilled drop from a million blossoms”. This was the letter that prompted Dickinson to write Higginson and suggests that Dickinson’s own imagery was inspired by Higginson.

And Attar so immense

From the familiar species

That perished by the Door —

We wonder it was not Ourselves

Arrested it — before —

Of Pictures, the Discloser —

That Dickinson uses the word “immense” suggests Higginson’s “million blossoms”. Also worth noting, I think, is the notion that what “perished by the Door” was made into attar. Keep that in the back of your mind. The narrator, standing by the gravestone, next expresses appreciation for the genius of poetry. The poet’s skill is such that she wonders why we don’t ourselves “arrest”/grasp/comprehend what poetry, after the fact, makes self-evident. Poetry is “Of Pictures” (possibly meaning imagery) the “Discloser”. That is, poetry is the art that reveals truth through the language of imagery, archetype, and symbol.

So far, so good. It's the last third of the poem where matters get muddled. [Note: For an interpretation I find more convincing and simpler than my own, be sure to read the comment section; then decide for yourself.]

The Poet — it is He —

Entitles Us — by Contrast —

To ceaseless Poverty —

Of portion — so unconscious —

The Robbing — could not harm —

Himself — to Him — a Fortune —

Exterior — to Time —

Now, here’s my thought: If we keep in mind that Dickinson, at the very outset of the poem distinguishes between two subjects, the Poet (deceased) and “Poetry”—the That that makes the perished into attar—we have the makings of a contrast. Dickinson even spells it out. “By Contrast—” she writes. The speaker returns our attention to the deceased Poet (after describing poetry’s power). That is, unlike his or her poetry, by contrast, the Poet will not be made into attar. The Poet has perished. It’s possible to break down these lines into three separate assertions:

The Poet — it is He —

Entitles Us — by Contrast —

To ceaseless Poverty —

The death of the Poet, in contrast to his poetry, is a cause of ceaseless Poverty. Ceaseless because his death is final. Dickinson isn’t referring to the The Poet, but to Death. Then she moves on to her next thought:

Of portion — so unconscious —

The Robbing — (!)

In a highly compressed fashion, she is accusing Death of thoughtlessness and indifference. Of portion, she says sarcastically, Death is unconscious/thoughtless/indifferent. In other words, she expresses dismay at Death’s indifference to the “portion” that is really being robbed from us—not just a man but a great artist—a Shakespeare, a Keats or a Brontë. She expresses dismay at Death’s indifference to who he robs from us.

— could not harm —

Himself — to Him — a Fortune —

Exterior — to Time —

Now she moves onto her third thought. And here, if I’m interpreting the poem correctly, Dickinson’s final lines remind me very much of the closing lines to her poem, Because I could not stop for Death:

Since then – 'tis Centuries – and yet

Feels shorter than the Day

There’s that same sense of timelessness—not the timelessness of paradise, but of awareness exiled from time’s rituals—a nothing that is both death and deathless. That is, just as with the narrator in Because I could not stop for Death, the Poet’s centuries feel shorter than the day. The conclusion just as laden with contradiction—but also consistent. According to biographers, Dickinson refused to “accept Christ” (and presumably the afterlife that went along with that) but she also seemed unwilling to accept the death of the soul. This may disappoint some metaphysical naturalists among my readers (and you know who you are) but asking Dickinson, in her era and culture, to throw the soul out with the Christian bathwater, is probably asking too much.

Though Death has robbed us of the Poet, Death cannot rob the Poet of his “Fortune”. The Poet takes what is most precious about him with him (Dickinson was untroubled, according to Vendler, by the use of He/Him in reference to herself as a poet). He takes his creative genius—his Fortune—into that deathless death that is exterior to time. Death can rob us of the poet’s creative genius, but cannot rob the Poet himself. “[Death] could not harm—Himself [the Poet]”. To Him—to himself—the poet’s Fortune is now exterior to time. Yet one is very hesitant to read this as triumphing over Death. Dickinson ends the poem, as with Because I could not stop for Death, with irreconcilable contradiction. She is both deceased and conscious. And that might be part of the point. The contradiction, the dissonance, is part of the tragedy.

- From Vendler’s Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries: “Dickinson here uses a capitalized universalized “he” in reference to the Poet; I follow her reverent practice. She assumes the ungendered nature of the Platonic Idea of the Poet. She would not have said that she meant to exclude, by the pronoun “He,” the women Poets whose works she admired: Elizabeth Barret Browning, George Eliot, and Emily Brontë.” [p. 212-213]

Edit: It’s tempting to read “Exterior — to Time” as the poet’s poetry triumphing over time. In other words, his fortune—his poetry—is exterior to death and time. The problem with this reading is that it seemingly contradicts the speaker’s earlier assertion that He entitles us to “ceaseless poverty”. One has to explain this apparent contradiction. My own way around this is to treat her final lines as a reference to the deceased Poet rather than to His or Her poetry (and Because I could not stop may give us a precedence for such a reading).

Worth mentioning is that she could be describing herself in This was a Poet—commenting on her own death. In this sense, This was a Poet and Because I could not stop for Death can be read as describing the same event—her own death. The former is from the perspective of the living, reflecting on the poet’s death, while the latter is from the perspective of the deceased poet.

I haven’t said much about Vendler or Miller’s interpretations because they’re so different from mine. I don’t know how to summarize their readings (and frankly find them somewhat scattershot and confusing). How exactly does Vendler land on plagiarism, for example? What and where does that come from? Vendler summarizes the closing couplet this way:

“Dickinson points out the degree to which the Poet’s capacity to notice, to notice everything, and then disclose His “Pictures,” makes us notice things too… And third, Dickinson points out the indifference of the Poet to us (or to anyone else), an indifference arising not from self-esteem but from His (to him unconscious) Fortune. He is so unaware of the grace bestowed on Him, of the great “Portion” of wealth He has inherited, that no robbing from his worth can harm Him (plagiarism of His work by others does not affect our recognition of the true Poet). He moves in a world (in Dickinson’s great phrase) “Exterior — to Time — “… He is as unaware of Time (and its obverse, Eternity) as He is of us. [p. 213-214]

So you can see how different our interpretations are. Vendler doesn’t even interpret the poem as being that of a deceased Poet (and this despite describing the opening line as a past-tense epitaph in the very first sentence of her analysis). According to Vendler, if I understand her correctly, Dickinson is describing the archetypal experience(?) of reading poetry. It seems to me that Vendler spends less time interpreting the poem than ‘biographizing’. Miller interprets the poem as Dickinson expressing (for lack of a better term) gender resentment(?). She reads Dickinson as addressing male poets (and not the Platonic Idea of the Poet) in her use of He, and frames the contrast as one of “difference and of strength”.

“As a younger sister of a favored son and as a consciously female poet, however, Dickinson might well differentiate herself with some resentment from the poet who creates unconsciously and with ease, the man of ceaseless, inherited cultural wealth. Evidently during this time when she wrote or at least copied “This was a Poet” for her own safekeeping, the contrast between herself as artist and the world was particularly vivid. In the fascicle where she binds this poem, Dickinson precedes it with two poems on similar differences. In the first, “It would have starved a Gnat — / To live so small as I — ” (612), the speaker brags that she can live on even less that a gnat, and without his privileges to fly to more sustaining places or to die. In the poem immediately preceding “This was a Poet,” the speaker is a “Girl” poet “shut… up in Prose — ” by uncomprehending adults, whom she escapes “easy as a Star” by willing herself to be free (613). Later in the fascicle Dickinson includes “It was given to me by the Gods” (454), a poem about another “little Girl” far richer with her handful of “Gold” than anyone could guess and richer than anyone else is: “The Difference — made me bold —” she confides. These are poems of difference and of strength, whether these qualities stem from unique starvation or mysterious wealth.” [Emily Dickinson: A Poet’s Grammar p. 120-121]

Miller interprets Dickinson’s use of That, in reference to the Poet, as suggesting the poet’s “lack of humanity”.

“The poet’s lack of humanity is further suggested by his peculair invulnerability in the last stanza: “a Fortune — / Exterior — to Time —” is glorious as a description of immortal poems but somewhat mechanical and materialistic as a description of a man. We are poor, capable of “wonder,” within “Time,” while He is alone, “Exterior” to our world, knowable only “by Contrast.” [p. 120]

“The poet/narrator who speaks in Dickinson’s poem considers herself a part of the admiring, ordinary crowd rather than separate from it. Her stance indicates that not all poets share “His” isolation from community.” [p. 121]

So, from Miller, we have a feminist critique based on a reading of He as a specifically gendered reference; and not, as Vendler asserts, a universalized He. It could be argued, in that respect, that Miller’s reading is potentially anachronistic (giving too much weight to the pronoun). Miller’s interpretation is also, arguably, based on reading the first two lines as one (which is not how Dickinson preserved the poem).

At any rate, there’s my 2 cents. Spend it how you will.

upinVermont | March 12 2024

Welcome! Please read some of my poetry while you’re here. Even if a post is two years old, they’re being read every day. They’re all current. Feel free to join the conversation. Lastly, treat this post as a Guest Book. Offer suggestions, improvements, requests or just say Hello! If you have a question concerning poetry or a poem, click read more at the end of this sentence and fill out the form. Continue reading

Welcome! Please read some of my poetry while you’re here. Even if a post is two years old, they’re being read every day. They’re all current. Feel free to join the conversation. Lastly, treat this post as a Guest Book. Offer suggestions, improvements, requests or just say Hello! If you have a question concerning poetry or a poem, click read more at the end of this sentence and fill out the form. Continue reading  Welcome! Please read some of my poetry while you’re here. Even if a post is two years old, they’re being read every day. They’re all current. Feel free to join the conversation. Lastly, treat this post as a Guest Book. Offer suggestions, improvements, requests or just say Hello! If you have a question concerning poetry or a poem, click read more at the end of this sentence and fill out the form. Continue reading

Welcome! Please read some of my poetry while you’re here. Even if a post is two years old, they’re being read every day. They’re all current. Feel free to join the conversation. Lastly, treat this post as a Guest Book. Offer suggestions, improvements, requests or just say Hello! If you have a question concerning poetry or a poem, click read more at the end of this sentence and fill out the form. Continue reading