- May 14, 2009 Tweaked & corrected some typos.

- March 30, 2023 More typos, spruced up, note on Chaucer added.

During the sixteenth century, which culminated in poets like Drayton, Sidney, Spenser, Daniel, and Shakespeare, English was seen as common and vulgar – fit for record keeping. Latin was still considered, by many, to be the language of true literature. Latin was essentially the second language of every educated Elizabethan and many poets, even the much later Milton, wrote poetry in Latin rather than English.

Iambic Pentameter originated as an attempt to develop a meter for the English language legitimizing English as an alternative and equal to Latin (as a language also capable of great poetry and literature).  Since meter was a feature of all great Latin poetry, it was deemed essential that an equivalent be developed for the English Language. But poets couldn’t simply adopt Latin’s dactylic hexameter or dactylic pentameter lines. Latin uses quantitative meter, a meter based on alternating long and short syllables. English, on the other hand, is an accentual language – meaning that words are “accented” or stressed while others are, in a relative sense, unstressed. (There are no long or short syllables in English, comparable to Latin.)

Since meter was a feature of all great Latin poetry, it was deemed essential that an equivalent be developed for the English Language. But poets couldn’t simply adopt Latin’s dactylic hexameter or dactylic pentameter lines. Latin uses quantitative meter, a meter based on alternating long and short syllables. English, on the other hand, is an accentual language – meaning that words are “accented” or stressed while others are, in a relative sense, unstressed. (There are no long or short syllables in English, comparable to Latin.)

False Starts

But this didn’t stop Elizabethan poets from trying. A circle of Elizabethan poets, including Sidney and Spenser, all tried to adapt quantitative meter to the English language. Here’s the problem. Even in their own day Latin and Classical Greek were dead languages – dead for a thousand years. Nobody knew what these languages really sounded like and we still don’t. Imagine if all memory of the French language vanished tomorrow (along with any recordings). French uses the same alphabet, but how would we know how to pronounce it? Americans would pronounce it like Americans, Germans would pronounce like Germans, etc… The French accent would be gone – forever. The same is true for Latin. So, while we may intellectually know that syllables were spoken as long or short, we have no idea how the language was actually pronounced. It’s tone and accent are gone. When the Elizabethans spoke Latin, they pronounced and accented Latin like Elizabethans. They assumed that this was how Latin had always been pronounced. For this reason, perhaps, Adopting the Dactylic hexameters of Latin didn’t seem so far-fetched.

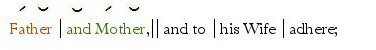

The Spenser Encyclopedia, from which I obtained the passage at right, includes the following “dazzling” example of quantitative meter in English:

The symbols used to scan the poem reflect Spenser’s attempt to imitate the long and short syllables of Latin. The experiments were lackluster. Spenser and Sidney moved on, giving up on the idea of reproducing long and short syllables. The development of Iambic Pentameter began in earnest. (Though Sidney continued to experiment with accentual hexameters – for more on this, check out my post on Sidney: His Meter & His Sonnets.)

Those were heady times. Iambic Pentameter was new and dynamic. Spenser adopted Iambic Pentameter with an unremitting determination. Anyone who has read the Faerie Queen knows just how determined. (That said, each Spenserian Stanza – as they came to be called – ended with an Alexandrine , an Iambic Hexameter line – as if Spenser couldn’t resist a reference to the Hexameters of Latin and Greek.)

- Note: It may be objected that iambic pentameter was not new, and point to Chaucer’s works—written in iambic pentameter. The curious thing about the Elizabethans, however, is that they couldn’t agree on how to scan Chaucer’s middle English, and so didn’t recognize it for what it was. And don’t forget that hundreds of years separated them from Chaucer, almost as much as separates us from Shakespeare. As George T. Wright wrote in Shakespeare’s Metrical Art: “In Hoccleve, Lydgate, and other English poets of the fifteenth century, the art of Chaucer’s iambic pentameter disintegrated. Lydgate’s lines are often monotonously regular; Hoccleve’s frequently appear to insist on stressing unlikely syllables. Whether the loss of the final –e was largely responsible for throwing their lines into disorder or whether, as seems likely, the odd character of their verse results from the conscious adoption of some bizarre species of decasyllabic line, the century and a quarter of versification between 1400 and about 1525 left iambic pentameter in so strange a state that, instead of taking off from where Chaucer had left it, poets from Wyatt on had, in effect, to begin all over again.”

Why the Drama?

Just as with Virgil and Homer for Epic Poetry, the Classical Latin and Greek cultures were admired for their Drama – Aeschylus, Terence, Aristophanes, Euripides, Sophocles. Classical drama was as admired as classical saga.

As Iambic Pentameter quickly began to be adopted by poets as an equivalent to the classical meters of Greek and Latin, dramatists recognized Iambic Pentameter as a way to legitimize their own efforts. In other words, they wanted to elevate their drama into the realm of serious, literary works – works of poetry meant to be held in the same esteem as the classical Greek and Latin dramas. Dramatists, especially during Shakespeare’s day, were held in ill-repute, to say the least. Their playhouses were invariably centers of theft, gambling, intoxication, and rampant prostitution. Dramatists themselves were considered nothing better than unprincipled purveyors of vulgarity – all too ready to serve up whatever dish the rabble wanted to gorge on.

There was some truth to that. The playhouses had to earn a living. The actors and dramatists, like Hollywood today, were more than willing to churn out the easy money-maker. Thomas Heywood, a dramatist and pamphleteer who was a contemporary of Shakespeare, claimed to have had “an entire hand or at least a main finger in two hundred and twenty plays”.

That said, aspirations of greatness were in the air. This was the Elizabethan Age – the small nation of England was coming into its own. The colonization of America was about to begin. The ships of England were establishing new trade routes. The Spanish dominance of the seas was giving way. England was ready to take its place in the world – first as a great nation, than as an empire. The poets and dramatists of the age were no less ambitious. Many wanted to equal the accomplishments of the Greeks and Romans – Marlowe, Shakespeare, Jonson, Webster, Beaumont and Fletcher, Middleton…

Ben Jonson, in his own lifetime, published a collection of his own works – plays and poetry. This was a man who took himself seriously. The Greeks and Romans wrote their Drama in verse, and so did he. The Romans and Greeks had quantitative meter, and now the Elizabethans had Iambic Pentameter – Blank Verse. Serious plays were written in verse, quick entertainments, plays meant to fill a week-end and turn a profit, were written in prose – The Merry Wives of Windsor, by Shakespeare, was written to entertain, was written quickly, and was written in prose.

As I’ve mentioned elsewhere, Sackville and Norton were the first dramatists to write Drama, the play Gorboduc, using Iambic Pentameter or, as it came to be known, blank verse. For a brief sample of their verse you can check out my post on The Writing & Art of Iambic Pentameter.

Poets and Poet/Dramatists were quick to recognize the potential in blank verse. Early Dramatists like Greene, Peele and Kyd were quick to adopt it. Their efforts bequeathed poetry to the new verse form, but it was  Christopher Marlowe who upped the ante by elevating not just the poetry but the verse form itself. Suddenly Iambic Pentameter was given a powerful new voice all of its own.

Christopher Marlowe who upped the ante by elevating not just the poetry but the verse form itself. Suddenly Iambic Pentameter was given a powerful new voice all of its own.

Hair standing on end, other poets soon referred to Marlowe’s blank verse as Marlowe’s Mighty Line. Reading Marlowe’s verse now, with 500 years of history between, the verse appears inflexible and monochromatic. It was Shakespeare who soon demonstrated to other poets the subtlety and flexibility that Blank Verse (Iambic Pentameter) was capable of. Shakespeare’s skill even influenced Marlowe (who had earlier influenced Shakespeare). Shakespeare’s influence is felt in Marlowe’s Faustus and Edward II, by which time Marlowe’s verse becomes more supple.

The passage above is spoken by Tamburlaine, who has been smitten by Zenocrate, “daughter to the Soldan of Egypt“. Up to meeting Zenocrate, Tamburlaine’s sole ambition had been to conquer and ruthlessly expand his empire. He’s a soldier’s soldier. But his passion for Zenocrate embarrasses him. He feels, in his equally blinding passion for her, that he “harbors thoughts effeminate and faint”.

Tamburlaine, with Marlowe’s inimitable poetry, readily rationalizes his “crush”. Utterly true to his character, he essentially reasons that beauty is a spoil rightly belonging to the valorous. He will subdue both (war and love), he pointedly remarks (rather than be subdued). After all, says Tamburlaine in a fit of self-adulation, if beauty can seduce the gods, then why not Tamburlaine? But make no mistake, it’s not that Tamburlaine has been subdued by love, no, he will “give the world note”, by the beauty of Zenocrate, that the “sum of glory” is “virtue”. In short, and in one of the most poetically transcendent passages in Elizabethan literature, Tamburlaine is the first to express the concept of a “trophy wife”.

Not to be missed is the Elizabethan sense of the word “virtue” – in reference to women, it meant modesty and chastity. Naturally enough, in men, it meant just the opposite – virility, potency, manhood, prowess. So, what Tamburlaine is saying is not that modesty and chastity are the “sum of glory”, but virility. The ‘taking’ of beautiful women, in the martial, sexual and marital sense, fashions “men with true nobility”. It’s no mistake that Marlowe chose “virtue”, rather than love, when writing for Tamburlaine. Tamburlaine’s only mention of love is in reference to himself—to fame, valor and victory, not affection.

Anyway, I couldn’t resist interpreting the passage just a little. So many readers tend to read these passages at face value – which, with Elizabethan poets, frequently misses the boat.

As to the meter… Notice how the meaning sweeps from one line to the next. Most of the lines are syntactically unbroken, complete units. This is partly what poets were referring to when they described Marlowe’s lines as “mighty”.  Notice also that that the whole of the speech can be read as unvarying Iambic Pentameter and probably should be.

Notice also that that the whole of the speech can be read as unvarying Iambic Pentameter and probably should be.

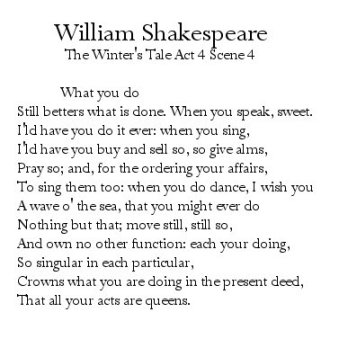

By way of comparison, at right is how Shakespeare was writing toward the end of his career. The effect he produced is far different. The iambic pentameter (Blank Verse) doesn’t sweep from one line to the next. The most memorable and beautiful image in this passage is when Florizel wishes Perdita, when she dances, to be like “a wave o’the sea”. And any number of critics have seen, in this passage, a graceful equivalent in the ebb and flow of Shakespeare’s blank verse. The syntactic units halt, then resume, then halt again, variably across the surface of the Iambic Pentameter pattern. The overall effect creates one of the most beautiful passages in all of Shakespeare, and not just for its content and imagery, but also for its supple verse. The Elizabethans, in Shakespeare, bettered the Greek and Romans. In 1598, Francis Meres, fully understanding the tenor of the times, wrote:

“As the Greeke tongue is made famous and eloquent by Homer, Hesiod, Euripedes, Aeschilus, Sophocles, Pindarus, Phocylides and Aristophanes; and the Latine tongue by Virgill, Ovid, Horace, Silius Italicus, Lucanus, Lucretius, Ausonius, and Claudianus: so the English tongue is mightily enriched, and gorgeously invested in rare ornaments and respledent abiliments by Sir Philip Sidney, Spencer, Daniel, Drayton, Warner, Shakespeare, Marlow and Chapman…

As the soule of Euphorbus was thought to live in Pythagoras : so the sweet wittie soule of Ovid lives in mellifluous & honytongued Shakespeare, witnes his Venus and Adonis, his Lucrece, his sugred Sonnets among his private frinds, &c…

As Plautus and Seneca are accounted the best for Comedy and Tragedy among the Latines : so Shakespeare among y’ English is the most excellent in both kinds for the stage; for Comedy, witnes his Ge’tleme’ of Verona, his Errors, his Love labors lost, his Love labours wonne, his Midsummer night dreame, & his Merchant of Venice : for Tragedy his Richard the 2. Richard the 3. Henry the 4. King John, Titus Andronicus and his Romeo and Juliet.

As Epius Stolo said, that the Muses would speake with Plautus tongue, if they would speak Latin : so I say that the Muses would speak with Shakespeares fine filed phrase, if they would speake English.”

Finally, the English were creating their own literary heritage. Up to now, if the English wanted to read great literature, they read Latin and Greek.

But Not Latin Enough

The Elizabethans and Jocabeans firmly established Iambic Pentameter as the great Meter of the English language. But the youth of each generation wants to reject and improve on their elders.  The Elizabethans and Jacobeans were old news to the eighteen and twenty year old poets who would found the restoration. They wanted to prove not just that they could find an alternative to quantitative meter, they wanted to prove that they could write just as well as the great Latin poets – English verse could be as great as Latin verse and in the same way. And so English poetry entered the age of the Heroic Couplet.

The Elizabethans and Jacobeans were old news to the eighteen and twenty year old poets who would found the restoration. They wanted to prove not just that they could find an alternative to quantitative meter, they wanted to prove that they could write just as well as the great Latin poets – English verse could be as great as Latin verse and in the same way. And so English poetry entered the age of the Heroic Couplet.

Poets had written heroic couplets before, but they were primarily open heroic couplets. The restoration poets wanted to reproduce the Latin distich – a verse form in which every rhyming couplet is also a distinct syntactic unit. This meant writing closed heroic couplets. If you want a clearer understanding of what this means, try my post About Heroic Couplets.

Anyway, the meter is still Iambic Pentameter, though the verse form has changed (Heroic, when attached to couplets, means couplets written in Iambic Pentameter). In other words, it’s not Iambic Pentameter with which the restoration poets were dissatisfied, it was unrhymed Iambic Pentameter (Blank Verse) which restoration poets found inadequate.  Like the Elizabethans, they wanted English literature to be the equal of Latin and Greek literature. Blank verse wasn’t enough.

Like the Elizabethans, they wanted English literature to be the equal of Latin and Greek literature. Blank verse wasn’t enough.

One of the best ways, perhaps, to get a feel for what restoration poets were trying to accomplish is to compare similar passages from translations. Below are three translations. The first is by George Chapman (Chapman’s Homer), an Elizabethan Poet and Dramatist, contemporary of Shakespeare and, some say, a friend of Shakespeare. Chapman writes Open Heroic Couplets – a sort of cross between blank verse and closed heroic couplets. The second translation is by Alexander Pope, a contemporary of Dryden and, with Dryden, the greatest poet of the restoration. He writes closed heroic couplets.

And now compare Pope’s translation to Robert Fitzgerald’s modern translation (1963). Fitzgerald writes blank verse and his translation is considered, along with Lattimore’s, the finest 20th Century translation available. I personally prefer Fitzgerald, if only because I prefer blank verse. Lattimore’s translation is essentially lineated prose (or free verse).

Which of these translations do you like best? Fitzgerald’s is probably the most accurate. Which comes closest to capturing the spirit of Homer’s original – the poetry? I don’t think that anyone knows (since no one speaks the language that Homer spoke).

All three of these translations are written in Iambic Pentameter but, as you can see, they are all vastly different: Open Heroic Couplets, Closed Heroic Couplets, and Blank Verse. The reasons for writing them in Iambic Pentameter, in each case, was the same – an effort to reproduce in English what it must have been like for the ancient Greeks to read Homer’s Dactylic Hexameters. Additionally, in the case of Chapman and Pope, it was an effort to legitimize the English language, once and for all, as a language capable of great literature.

Enough with the Romans and Greeks

Toward the end of the restoration, Iambic Pentameter was no longer a novelty. The meter had become the standard meter of the English language. At this point one may wonder why. Why not Iambic Tetrameter, or Iambic Hexameter? Or why not Trochaic Tetrameter?

These are questions for linguists, neuro-linguists and psycho-linguists. No one really knows why Iambic Pentameter appeals to English speakers. Iambic Tetrameter feels too short for longer poems while hexameters feel wordy and overlong. There’s something about the length of the Iambic Pentameter line that suits the English language. Theories have been put forward, none of them without controversy. Some say that the Iambic Pentameter line is roughly equivalent to a human breath. M.L. Harvey, in his book Iambic Pentameter from Shakespeare to Browning (if memory serves) offers up such a theory.

Interestingly, every language has found its own normative meter. For the French language, its hexameters (or Alexandrines), for Latin and Greek it was dactylic Hexameter and Pentameter). Just as in English, no one can say why certain metrical lengths seem to have become the norm in their respective languages. There’s probably something universal (since the line lengths of the various languages all seem similar and we are all human) but also unique to the qualities of each language.

Anyway, once Iambic Pentameter had been established, poets began to think that translating Homer and Virgil, yet again, was getting somewhat tiresome. English language Dramatists had already equaled and excelled the drama of the Romans and Greeks. The sonnet sequences of Drayton, Daniel, Shakespeare, Sidney and Spenser proved equal to the Italian Sonnets of Petrarch (in the minds of English poets at least). The restoration poets brought discursiveness to poetry. They used poetry to argue and debate. The one thing that was missing was an epic unique to the English language. Where was England’s Homer? Virgil? Where was England’s Odyssey?

Enter Milton

Milton, at the outset, didn’t know he was going to write about Adam & Eve.

He was deeply familiar with Homer and Virgil. He called Spenser his “original”, the first among English poets and a “better teacher than Aquinus”.  But Spenser’s Faerie Queen was written in the tradition of the English Romance. It lacked the elevated grandeur of a true epic and so Milton rejected it. He was also familiar with Dante’s Divine Comedy. But the reasons for Milton choosing the story of Adam & Eve are less important, in this post, than the verse form that he chose. At first, writing in the age of the heroic couplet, Milton’s intention was to use the verse of his peers. But Milton was losing his eyesight. That and the constraints Heroic Couplets placed on narrative were too much. He chose Blank Verse.

But Spenser’s Faerie Queen was written in the tradition of the English Romance. It lacked the elevated grandeur of a true epic and so Milton rejected it. He was also familiar with Dante’s Divine Comedy. But the reasons for Milton choosing the story of Adam & Eve are less important, in this post, than the verse form that he chose. At first, writing in the age of the heroic couplet, Milton’s intention was to use the verse of his peers. But Milton was losing his eyesight. That and the constraints Heroic Couplets placed on narrative were too much. He chose Blank Verse.

- September 2023. I reader recently asked me if I meant to suggest that the reason Milton chose blank verse was because of his blindness. It’s been a while since I wrote that “Milton’s intention was to use the verse of his peers” and I no longer remember what my source was. Milton, in his own introduction to Paradise Lost, refers to blank verse as “English heroic verse without rhyme” and writes: “rhyme being no necessary adjunct or true ornament of poem or good verse…[it is] the invention of a barbarous age.” “[A]ncient liberty [has been] recovered to heroic poem from the troublesome and modern bondage of rhyming.” The critical consensus is that Milton chose blank verse because his models (which he wished to rival) were the great epics of Greek and Latin, and these were not rhymed.

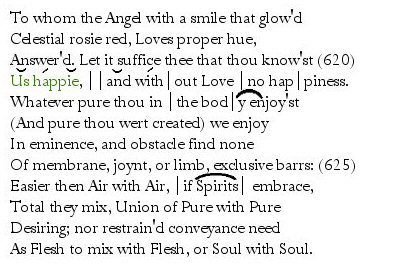

In the end, the genius of Milton’s prosody and narrative conferred on blank verse the status it needed. Blank verse became the language of epic poetry – not heroic couplets; Milton’s blank verse was the standard against which the poetry of all other epic poems would be measured. From this point forward, later poets would primarily draw their inspiration from the English poets that had come before (not the poets of classical Greece or Rome).![Paradise Lost Book 8 [Extract] Paradise Lost Book 8 [Extract]](https://poemshape.files.wordpress.com/2009/04/paradise-lost-book-8.jpg?w=310&h=456) Paradise Lost successfully rivaled the Odyssey and the Iliad.

Paradise Lost successfully rivaled the Odyssey and the Iliad.

The extract at right is from Book 8 of Paradise Lost. Adam, naturally enough, wants to know about the cosmos. Since reading up on Cosmology is one of my favorite pastimes, I’ve always liked this passage. The extract is just the beginning. Milton has an educated man’s knowledge of 17th Century Cosmology, but must write as if he knows more than he does. In writing for Raphael however (the Angel who describes the Cosmos to Adam), Milton must write as though Raphael admits less than he knows. The effect is curious. At the outset, Raphael says that the great Architect (God) wisely “concealed” the workings of the Cosmos; that humanity, rather than trying to “scan” God’s secrets, “ought rather admire” the universe! This is a convenient dodge. Raphael then launches into a series of beautifully expressed rhetorical questions that neatly sum up Cosmological knowledge and ignorance in Milton’s day. It is a testament to the power of poetry & blank verse that such a thread-bare understanding of the universe can be made to sound so persuasively knowledgeable. Great stuff.

With Milton, the English Language had all but established its own literature; and Iambic Pentameter, until the 20th Century, was the normative meter in which all English speaking poets would measure themselves.

The Novelty Wears Off

After the restoration poets, the focus of poets was less on meter than on subject matter. Poets wrote in Iambic Pentameter, not because they were thirsting for a new expressive meter in their own language, but because it’s use was expected. Predictably, over the next century and a half, Iambic Pentameter became rigid and rule bound. The meter was now a tradition which poets were expected to work within.

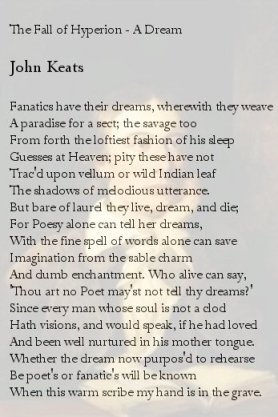

This isn’t to say that great poetry wasn’t written during the eighteenth and nineteenth century. Keats’ Hyperion, short as it was, equaled and exceeded the masterful Blank Verse of Milton (perhaps some of the most beautiful blank verse ever written) – but the beauty was in his phrasing, imagery and language, not in any novel use of Iambic Pentameter. Wordsworth wrote The Prelude and Browning wrote an entire novel, The Ring & the Book, using blank verse. There was Shelley and Tennyson, but none of them developed Iambic Pentameter beyond the first examples of the Elizabethans—and for most, their blank verse was even a step backwards. By and large, the blank verse of the Victorians is mechanical and pro forma, lacking the flexibility and innovations of the Elizabethans.

This isn’t to say that great poetry wasn’t written during the eighteenth and nineteenth century. Keats’ Hyperion, short as it was, equaled and exceeded the masterful Blank Verse of Milton (perhaps some of the most beautiful blank verse ever written) – but the beauty was in his phrasing, imagery and language, not in any novel use of Iambic Pentameter. Wordsworth wrote The Prelude and Browning wrote an entire novel, The Ring & the Book, using blank verse. There was Shelley and Tennyson, but none of them developed Iambic Pentameter beyond the first examples of the Elizabethans—and for most, their blank verse was even a step backwards. By and large, the blank verse of the Victorians is mechanical and pro forma, lacking the flexibility and innovations of the Elizabethans.

The Fall of Iambic Pentameter

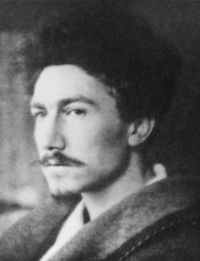

By the end of the Victorian Era (1837-1901), and in the hands of the worst poets, Iambic Pentameter had become little more than an exercise in filling-in-the-blanks. The rules governing the meter were inflexible and predictable. It was time for a change. The poet most credited with making that change is Ezra Pound. Whether or not Pound was, himself, a great poet, remains debatable. Most would say that he was not. What is indisputable is his influence on and associations with poets who were great or nearly great: Yeats, T.S. Eliot (whose poetry he closely edited),  Frost, William Carlos Williams, Marriane Moore. It was Pound who forcefully rejected the all too predictable sing-song patterns of the worst Victorian verse, who helped initiate the writing of free verse among English speaking poets. And the free verse that Pound initiated has become the indisputably dominant verse form of the 20th century and 21st century, more pervasive and ubiquitous than any other verse form in the history of English Poetry – more so than all metrical poems combined. While succeeding generations during the last 100 years, in one way or another, have rejected almost every element of the prior generation’s poetics, none of them have meaningfully questioned their parents’ verse form. The ubiquity and predictability of free verse has become as stifling as Iambic Pentameter during the Victorian era.

Frost, William Carlos Williams, Marriane Moore. It was Pound who forcefully rejected the all too predictable sing-song patterns of the worst Victorian verse, who helped initiate the writing of free verse among English speaking poets. And the free verse that Pound initiated has become the indisputably dominant verse form of the 20th century and 21st century, more pervasive and ubiquitous than any other verse form in the history of English Poetry – more so than all metrical poems combined. While succeeding generations during the last 100 years, in one way or another, have rejected almost every element of the prior generation’s poetics, none of them have meaningfully questioned their parents’ verse form. The ubiquity and predictability of free verse has become as stifling as Iambic Pentameter during the Victorian era.

But not all poets followed Pound’s lead.

A wonderful thing happened. With the collapse of the Victorian aesthetic, poets who still wrote traditional poetry were also freed to experiment. Robert Frost, William Butler Yeats, E.E. Cummings,  Wallace Stevens all infused Iambic Pentameter with fresh ideas and innovations. Stevens, Frost and Yeats stretched the meter in ways that it hadn’t been stretched since the days of the Elizabethan and Jacobean Dramatists. Robert Frost’s genius for inflection in speech was greatly enhanced by his anapestic variant feet. His poems, The Road Not Taken, and Birches both exhibit his innovative use of anapests to lend his verse a more colloquial feel. The links are to two of my own posts.

Wallace Stevens all infused Iambic Pentameter with fresh ideas and innovations. Stevens, Frost and Yeats stretched the meter in ways that it hadn’t been stretched since the days of the Elizabethan and Jacobean Dramatists. Robert Frost’s genius for inflection in speech was greatly enhanced by his anapestic variant feet. His poems, The Road Not Taken, and Birches both exhibit his innovative use of anapests to lend his verse a more colloquial feel. The links are to two of my own posts.

T.S. Eliot interspersed passages of free verse with blank verse that was both experimentally modern and deliberately suffused with the gait of the Elizabethans.

Wallace Stevens, like Thomas Middleton, pushed Iambic Pentameter to the point of dissolution. But Stevens’ most famous poem, The Idea of Order at Key West, is elegant blank verse – as skillfully written as any poem before it.

Yeats also enriched his meter with variant feet that no Victorian poet would have attempted. His great poem, Sailing to Byzantium, is written in blank verse, as is The Second Coming.

Yeats, Frost, Stevens, Eliot, Pound all came of age during the closing years of the Victorian Era. They carry on the tradition of the last 500 years, informed by the innovations of their contemporaries. They were the last. Poets growing up after the moderns have grown up in a century of free verse. As with all great artistic movements, many practitioners of the new free-verse aesthetic were quick to rationalize their aesthetic by vilifying the practitioners of traditional poetry. Writers of metrical poetry were accused (and still are) of anti-Americanism (poetry written in meter and rhyme were seen as beholden to British poetry), patriarchal oppression (on the baseless assertion that meter was a male paradigm), of moral and ethical corruption. Hard to believe? The preface to Rebel Angels writes:

One of the most notorious attacks upon poets who have the affrontery to use rhyme and meter was Diane Wakoski’s essay, “The New Conservatism in American Poetry” (American Book Review, May-June 1986), which denounced poets as diverse as John Holander, Robert Pinsky, T.S. Eliot, and Robert Frost for using techniques Wakoski considered Eurocentric. She is particularly incensed with younger poets writing in measure.

The preface goes on to note that Wakoski called Holander, “Satan”. No doubt, calling the use of Meter and Rhyme a “Conservative” movement (this at the height of Reaganism), was arguably the most insulting epithet Wakoski could hurl. So, religion, nationalism and politics were all martialed against meter and rhyme. The hegemony of free verse was and is hardly under threat. The vehemence of Wakoski’s attacks, anticipated and echoed by others, has the ring of an aging and resentful generation fearing (ironically) the demise of its own aesthetics at the hand of its children (which is why she was particularly incensed with younger poets). How dare they reject us? Don’t they understand how important we are?

But such behavior is hardly limited to writers of free verse. The 18th century Restoration poets behaved just the same, questioning the character of any poet who didn’t write heroic couplets. Artistic movements throughout the ages have usually rationalized their own tastes at the expense of their forebears while, ironically, expecting and demanding that ensuing generations dare not veer from their example.

Poets who choose to write Iambic Pentameter after the moderns are swimming against a tidal wave of conformity – made additionally difficult because so many poets in and out of academia no longer comprehend the art of metrical poetry. In some halls, it’s a lost art.

Part of the cause is that poets of the generation immediately following the moderns “treated Iambic Pentameter more as a point of departure than as a form consistently sustained.” Robert B. Shaw, in his book, Blank Verse: A Guide to its History and Use, goes on to write, “the great volume and variety of their modernist-influenced experiments make this period a perplexing one for the young poet in search of models.” (p. 161)

Part of the cause is that poets of the generation immediately following the moderns “treated Iambic Pentameter more as a point of departure than as a form consistently sustained.” Robert B. Shaw, in his book, Blank Verse: A Guide to its History and Use, goes on to write, “the great volume and variety of their modernist-influenced experiments make this period a perplexing one for the young poet in search of models.” (p. 161)

Poets like Delmore Schwartz and Randall Jarrell were uneven poets – moving in and out of Iambic Pentameter. Their efforts aren’t compelling. Karl Shapiro brought far more knowledge to bear. Robert Shaw offers up a nice quote from Shapiro:

The absence of rhyme and stanza form invites prolixity and diffuseness–so easy is it to wander on and on. And blank verse [Iambic Pentameter] has to be handled in a skillful, ever-attentive way to compensate for such qualities as the musical, architectural, and emphatic properties of rhyme; for the sense of direction one feels within a well-turned stanza; and for the rests that come in stanzas. There are no helps. It is like going into a thick woods in unfamiliar acres. (p. 137)

And some poets like to go into thick woods and unfamiliar acres. (This is, after all, still a post on why poets write Iambic Pentameter. And here is one poet’s answer.) The writing of a metrical poem, Shapiro seems to be saying, forces one to navigate in ways that free verse poets don’t have to. The free verse poet must consider content as the first and foremost quality of his or her poem. For the poet writing meter and rhyme, Shapiro implies, there is a thicket of considerations that go beyond content.

There is also John Ciardi, Howard Nemerov and, perhaps the greatest of his generation, Richard Wilbur. Wilbur writes:

There are not so many basic rhythms for American and English poets, but the possibilities of varying these rhythms are infinite. One thing modern poets do not write, thank heaven, is virtuoso poems of near perfect conformity to basic rhythms as Byron, Swinburne, and Browning did in their worst moments. By good poets of any age, rhythm is generally varied cleverly and forcefully to abet the expressive purposes of the whole poem. (p. 189)

By rhythms, Wilbur is referring to meters. Wilbur is essentially stating that when the good poet chooses to write meter, (Iambic Pentameter let’s say), he sees the rhythm (the metrical pattern) as something which, when cleverly varied, “[abets] the expressive purposes of the whole poem”. It’s a poetic and linguistic tool unavailable to the free verse poet. Period.

Robert Frost, who lived into the latter half of the 20th Century, famously quipped in response to free-verse poet Carl Sandburg:

“Writing free verse is like playing tennis with the net down.”

As free verse asserted an absolute domination over the poetic aesthetic, writing meter and rhyme increasingly became an act of non-conformity, even defiance. It’s in this spirit that a small group of poets, who ended up being called “New Formalists”, published a book called Rebel Angels in the mid 1990’s – the emphasis being on Rebel. The most recognizable names in the book were Dana Goioia, R.S. Gwynn, and Timothy Steele. The preface, already quoted above, attempts to frame its poets as revolutionaries from word one:

As free verse asserted an absolute domination over the poetic aesthetic, writing meter and rhyme increasingly became an act of non-conformity, even defiance. It’s in this spirit that a small group of poets, who ended up being called “New Formalists”, published a book called Rebel Angels in the mid 1990’s – the emphasis being on Rebel. The most recognizable names in the book were Dana Goioia, R.S. Gwynn, and Timothy Steele. The preface, already quoted above, attempts to frame its poets as revolutionaries from word one:

Revolution, as the critic Monroe Spears has observed, is bred in the bone of the American character. That character has been manifest in modern American poetry in particular. So it is no surprise that the most significant development in recent American poetry has been a resurgence of meter and rhyme, as well as narrative, among large numbers of younger poets, after a period when these essential elements of verse had been surpressed.

The word “American” turns up in each of the three (first three) introductory sentences. Lest there be any mistake, the intent was to frame themselves not as Eurocentric poets beholden to an older European tradition, but as American Revolutionaries. So what does that make the poets and critics who criticize them? – un-American? -establishmentarian? – conformist? – royalist conservatives?

So it goes.

If the intent was to initiate a new movement, the movement landed with a thud. The book is out of print and, as far as I know, few to none of the books by those “large numbers of younger poets” have actually made it onto bookshelves. The poems in the anthology are accomplished and competent, but not transcendent. None of the poets wrote anything for the ages.

The rebellion was short lived.

Modern Iambic Pentameter

Nowadays, I personally don’t notice the fierce partisanship of the previous decades. Most of the fiercest dialectic seems to be between the various schools of free verse poetics. Traditional poetry, the poetry of meter and rhyme, is all but irrelevant even as all the best selling poetry remains in meter and rhyme! – Robert Frost, Yeats, E.E. Cummings, Stevens, Shakespeare, Shelley, Keats, Millay, Dr. Seuss, Mother Goose and the thousands of nursery rhymes that are sold to new parents.

But why do poets write Iambic Pentameter nowadays?

But why do poets write Iambic Pentameter nowadays?

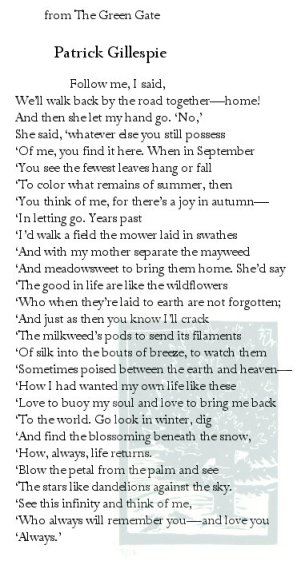

As far as I know, I am one of the few poets of my own generation (Generation X) writing in form, along with A.E. Stallings and Catherine Tufariello. And why do I write Iambic Pentameter? Because I like it and because I can produce effects that no poet can produce writing free verse. I’ve talked about some of those effects when analyzing poems by Shakespeare, his Sonnet 116, John Donne’s “Death be not Proud”, and Frost’s Birches. I use all of the techniques, found in these poems, in my own poetry.

I write about traditional poetry with the hope that an ostensibly lost art form can be fully enjoyed and appreciated.

One of my favorite moments in the Star Wars series is when Ben Kenobi kills General Grievous with a blaster instead of a Light Saber. Kenobi tosses down the blaster saying: “So uncivilized.” Blasters do the job. But it’s the Light Saber that makes the Jedi. There are just a few poets who really understand meter and rhyme.

But enough with delusions of grandeur. At right is an extract from one of my own poems. You can click on the image to see the full poem. One of my latest poems (as of 2010), written in blank verse, is Erlkönigen.

To write poetry using meter or rhyme, these days, is to be a fringe poet – out of step and, in some cases, treated with disdain and contempt by poets writing in the dominant free verse aesthetic.

There has never been a better time to be a fringe poet! It’s usually where the most innovative work is done.

- Note: There are critics & poets who deny that meter “exists”. I tend to group them with flat-earthers and moon landing denialists. Dan Schneider, of Cosmoetica, is one of them. If you’re curious to read my response to some of his writing, read Critiquing the Critic: Is Meter Real.

One Last Comparison

Going back to Homer’s Odyssey. One of the genres in which iambic pentameter still flourishes is in translating, suitably enough, Latin and Greek epic poetry. Here is one more modern Blank Verse (Iambic Pentameter) translation by Allen Mandelbaum, compared to Robert Fitzgerald’s (which we’ve already seen above). Mandalbaum’s translation was completed in 1990 – Fitzgerald’s in 1963. Seeing the same passage and content treated by two different poets gives an idea of how differently Iambic Pentameter can be treated even in modern times. The tone and color of the verse, in the hands of Fitzgerald and Mandelbaum, is completely different. I still can’t decide which I like better, though readers familiar with the original claim that Fitzgerald’s is more faithful to the tone of the original.

- Here’s a good article on blank verse, mostly because of it’s generous links: Absolute Astronomy.

Afterthoughts • August 7 2010

With some distance from this post, I realize that I never discussed meter’s origins. And it is this: Song. In every culture that I’ve explored (in terms of their oldest recorded poetry) all poems originated as lyrics to popular songs. Recently discovered Egyptian poems strongly suggest that they originated as lyrics to songs. If you read Chinese poetry, you will discover (dependent on the translator’s willingness to note the fact) that a great many of the poems were written to the tune of this or that well-known song. Likewise, the meter of ancient Greek poetry is also said to be based on popular song tunes. Many scholars believe that the Odyssey was originally chanted by story tellers though no one knows whether the recitation might have been acco mpanied.

mpanied.

The first poems from the English continent are Anglo-Saxon. The alliterative meter of these poems, as argued by some, are a reflection that they too were written to the tune of this or that song. The early 20th century critic William Ellery Leonard, for example, held “that our meter of “Sing a Song of Six-Pence” is directly descended from the Anglo-Saxon meter of Beowulf” [Creative Poetry: A Study of its Organic Principles p. 252]. Though none of his poetry survives, Aldhelm, bishop of Sherborne (d. 709), is said to have performed his secular songs while accompanied on the harp. None of Aldhelm’s Anglo-Saxon poetry remains. What is known to us is related by the ancient English historian Willliam of Malmesbury.

In short, meter is the remnant of music’s time signature.

The roots of Iambic Pentameter are in song (just as meter in every language and culture appears to be rooted in song and music). And it’s for this reason that the twaddle of a Dan Schneider is so misleading. Likewise, poets like Marriane Moore who postured over the artificiality of meter, were ignorant of meter’s origins. Arguments over the naturalness of meter are irrelevant. Iambic Pentameter is no more natural to the English language than the elaborate meter and rhyme of a rapper. It’s an art.

And it’s this that separates Free Verse from Traditional Poetry.

- Image above right: Fragment of an ancient Greek song.

Conversely, free verse is not rooted in music but only imitates the typographical presentation (the lineation) of metrical poetry. Why make this distinction? Because it’s another reason why poets write Iambic Pentameter. Writing metrical poetry is an acknowledgement of poetry’s musical roots. Meter acknowledges our human capacity to find rhythm and pattern within language (as within all things). I won’t argue that it’s a better way to write poetry. However, I will argue that writing meter is to partake in a tradition of poetry that is ancient and innate.

This one is trickier. In modern English, we pronounce attribute as att’ribute when used as a noun and attri’bute when used as a verb. Milton, in a rather Elizabethan twist, is using attributing in its nominal sense, rather than verbal sense. He therefore keeps the nominal pronunciation: att’tributing.

This one is trickier. In modern English, we pronounce attribute as att’ribute when used as a noun and attri’bute when used as a verb. Milton, in a rather Elizabethan twist, is using attributing in its nominal sense, rather than verbal sense. He therefore keeps the nominal pronunciation: att’tributing.

As early as the sixteenth century, Cervantes had killed the romance with Don Quixote, a novel which was both the culmination and the greatest parody of the romance form, and which introduced a new style of prose narrative in what Northrop Frye calls the “low mimetic” mode. Low mimetic writing deals with the life of ordinary people, with the everyday life we live, seen from the inside, where the mythic and high mimetic modes treat the life of heroes and kings, seen from the outside.(i)

As early as the sixteenth century, Cervantes had killed the romance with Don Quixote, a novel which was both the culmination and the greatest parody of the romance form, and which introduced a new style of prose narrative in what Northrop Frye calls the “low mimetic” mode. Low mimetic writing deals with the life of ordinary people, with the everyday life we live, seen from the inside, where the mythic and high mimetic modes treat the life of heroes and kings, seen from the outside.(i)

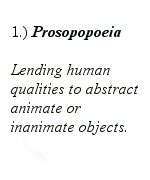

The figure prosopopoeia v, personification, is found in the poetry of Homer, medieval sagas and epics, and naturally enough in Milton; though which, in the serious poetry of the twentieth century has all but died out vi. It is telling that it is alive and well in the literature of high fantasy, which “[treats] the life of heroes and kings.”

The figure prosopopoeia v, personification, is found in the poetry of Homer, medieval sagas and epics, and naturally enough in Milton; though which, in the serious poetry of the twentieth century has all but died out vi. It is telling that it is alive and well in the literature of high fantasy, which “[treats] the life of heroes and kings.” A second figure, perhaps less common today, found in epic poetry is amplificatio vii. The Longman Dictionary of Poetic Terms provides the following definition:

A second figure, perhaps less common today, found in epic poetry is amplificatio vii. The Longman Dictionary of Poetic Terms provides the following definition: The third figure which will be considered in the creation of the oratorical style is called the Trope. Again referring to The Longman Dictionary of Poetic Terms the following definition is offered:

The third figure which will be considered in the creation of the oratorical style is called the Trope. Again referring to The Longman Dictionary of Poetic Terms the following definition is offered:

Another figure, antisagoge, especially with the conjunctive FOR, is ubiquitous especially in the prose of fable and fairy tale but is also found in fantasy. It is rarely found, significantly, outside of these genres. It is often over-used by clumsy writers because of its feeling that it elevates prose. The Longman Dictionary offers the following definition:

Another figure, antisagoge, especially with the conjunctive FOR, is ubiquitous especially in the prose of fable and fairy tale but is also found in fantasy. It is rarely found, significantly, outside of these genres. It is often over-used by clumsy writers because of its feeling that it elevates prose. The Longman Dictionary offers the following definition: The next figure, one of the most common of the six figures considered here, found especially in the prose of high fantasy, and especially in the writing Le Guin, is Acervatio or, as it is more commonly known in Greek, polysyndeton. The Longman Dictionary of Poetic Terms again provides the definition defining it as “a grammatical device of rhythm and balance in rhetoric that employs the repetition of conjunctions to effect measured thought and solemnity…” (Bold by Author) It should be noted that Quintillion includes adverbs and pronouns as characteristic connecting particles. xiv It is a rhetorical device which, if we are to use Milton’s Paradise Lost as a model of the high mimetic mode, finds its home most clearly in this mode. The following example will suffice as the figure is so frequent as to need no further examples.

The next figure, one of the most common of the six figures considered here, found especially in the prose of high fantasy, and especially in the writing Le Guin, is Acervatio or, as it is more commonly known in Greek, polysyndeton. The Longman Dictionary of Poetic Terms again provides the definition defining it as “a grammatical device of rhythm and balance in rhetoric that employs the repetition of conjunctions to effect measured thought and solemnity…” (Bold by Author) It should be noted that Quintillion includes adverbs and pronouns as characteristic connecting particles. xiv It is a rhetorical device which, if we are to use Milton’s Paradise Lost as a model of the high mimetic mode, finds its home most clearly in this mode. The following example will suffice as the figure is so frequent as to need no further examples. The final figure, hyperbaton, is such a frequent figure in the realm of fable, fairy tale, and high fantasy as to need little explanation. It is a “generic name for rhetorical figures that work through a reorganization of normal word order.” A specific type of hyperbaton, for example, is anastrophe (involving only two words), a “grammatical construction in which an INVERSION or reversal of the normal word order takes place for the sake of emphasis in meaning, rhythm, melody or tone.” xvii Tolkien uses hyperbaton and its various types throughout The Lord of the Rings where it heightens the tone of the language. “Like a deer he sprang away. Through the trees he sped. On and on he led them, tireless and swift, now that his mind was at last made up. The woods about the lake they left behind.” xviii It is also especially frequent where the intent of the author writing fantasy is to obsolesce the language spoken by the characters.

The final figure, hyperbaton, is such a frequent figure in the realm of fable, fairy tale, and high fantasy as to need little explanation. It is a “generic name for rhetorical figures that work through a reorganization of normal word order.” A specific type of hyperbaton, for example, is anastrophe (involving only two words), a “grammatical construction in which an INVERSION or reversal of the normal word order takes place for the sake of emphasis in meaning, rhythm, melody or tone.” xvii Tolkien uses hyperbaton and its various types throughout The Lord of the Rings where it heightens the tone of the language. “Like a deer he sprang away. Through the trees he sped. On and on he led them, tireless and swift, now that his mind was at last made up. The woods about the lake they left behind.” xviii It is also especially frequent where the intent of the author writing fantasy is to obsolesce the language spoken by the characters.

This turn hath made amends; thou hast fulfill’d

This turn hath made amends; thou hast fulfill’d

“You know. . .if I had my way, I’d send that genius son of a bitch an engraved invitation in iambic pentameter: A challenge in two stanzas to meet me alone in the desert. I’ll deliver it. Rommel in his tank and me in mine. We’d stop about paces. We’d get out, we’d shake hands. . . then we’d button up and do battle, just the two of us. That battle would decide the outcome of the war. It’s too bad jousting’s gone out of style.”

“You know. . .if I had my way, I’d send that genius son of a bitch an engraved invitation in iambic pentameter: A challenge in two stanzas to meet me alone in the desert. I’ll deliver it. Rommel in his tank and me in mine. We’d stop about paces. We’d get out, we’d shake hands. . . then we’d button up and do battle, just the two of us. That battle would decide the outcome of the war. It’s too bad jousting’s gone out of style.” [First, if you came to this post looking for information on Shakespeare & Iambic Pentameter, the symbols used and how to scan Shakespeare, take a look at my

[First, if you came to this post looking for information on Shakespeare & Iambic Pentameter, the symbols used and how to scan Shakespeare, take a look at my

That being said, I do not wish to discourage anyone from reading Mr. Harvey’s work. Objections like those mentioned in this review are inevitable when dealing with something so subjective and changeable as the pronunciation of the English language. Mr. Harvey’s undertaking is not an enviable one and the objections so far raised are less than his successes. Mr. Harvey’s reasoning is, for the better part, solid and insightful. In fact, to be fair, one should spend as much time sampling his successes. This, however, would only restate what is already well-stated by Mr. Harvey. Most notably, he convincingly answers (in this reader’s opinion) why poets prefer iambic verse to trochaic verse-no mean feat and a question which clearly fascinates Mr. Harvey.

That being said, I do not wish to discourage anyone from reading Mr. Harvey’s work. Objections like those mentioned in this review are inevitable when dealing with something so subjective and changeable as the pronunciation of the English language. Mr. Harvey’s undertaking is not an enviable one and the objections so far raised are less than his successes. Mr. Harvey’s reasoning is, for the better part, solid and insightful. In fact, to be fair, one should spend as much time sampling his successes. This, however, would only restate what is already well-stated by Mr. Harvey. Most notably, he convincingly answers (in this reader’s opinion) why poets prefer iambic verse to trochaic verse-no mean feat and a question which clearly fascinates Mr. Harvey.