Monthly Archives: January 2009

February 2009 Issue of Lynx

I just received an E-mail that the February on-line issue of Lynx is available.

The intro to the E-Zine states the following:

Lynx was started as APA-Renga by Tundra Wind (Jim Wilson) of Monte Rio, California, in 1985. Tundra was active in Amateur Publishing Associations (APAs) – groups of writers who shared their work by sending copies of their writings to a central location which were then collated and sent on to the other subscribers.

The editors are Jane and Werner Reichhold. I’ve reviewed Jane’s book, Basho, and an interview with Jane Reichhold can be found in the Vermont Poetry Newsletter of January 8th, 2009 (the Newsletter and interview are not mine).

I’ve been reading some of the poetry on the E-Zine. I’ve always been attracted to the intensely imagistic quality of haiku – no time for discourse, confession, rhetoric. The poem lives or dies on the depth, insight and vividness of a single observation. *This* is poetry and it is an attribute that many of our modern poets, with poems chalk full of pedestrian imagery, have either abandoned, overlooked, or are incapable of. A sample from the E-Zine:

ILUKO HAIKU

Alegria Imperial

batbato inta

kapanagan

sabsabong ti sardam

stones

on the riverbank

dawn flowers

daluyon iti

tengga’t aldaw

ararasaas mo

billows

at high tide

your whispers

bulan nga

agpadaya

magpakada kadi?

setting moon

in the east

did you say goodbye?

inururot

nga Pagay

tedted ti lulua

pulled strands

of rice grain

tear drops

dagiti bulbulong

nga agtataray

lenned diay laud

rustle

of leaves

sun set

![]()

[I have posted this information from the notice.]

BOOK REVIEWS

White Petals by Harue Aoki. Shichigatsudo Ltd. Tokyo, Japan. ISBN: 978-4-87944-120-1. Perfect bound with glassine dust jacket, 5 x 7.25 inches, Introduction by Sanford Goldstein, 130 pages, ¥1500. The Unworn Necklace by Roberta Beary, edited by John Barlow. Snapshot Press, P.O Box 123, Waterloo, Liverpool, United Kingdom L22 8WZ: 2007. Trade perfect bound with color cover, 5.5 x 8.5 inches, 80 pages one haiku per page. US$14; UK£7.99.

Seeing It Now: haiku & tanka by Marjorie Buettner. Red Dragonfly Press, press-in-residence at the Anderson Center, P.O. Box 406, Red Wing, MN 55066. Cover illustration by Jauneth Skinner. Introduction by H.F. Noyes. Perfect bound, 5.5 x 8.5, 44 pages, $15. ISBN:978-1-890193-85-0.

Songs Dedicated to my Mother Julia Conforti by Gerard J. Conforti AHA Online Books, 2008.

Kindle of Green by Cherie Hunter Day and David Rice. Letterpress on emerald Stardream cover and hand-sewn binding by Swamp Press. Illustrations by Cherie Hunter Day. ISBN: 978-0-934714-36-5, 48 pages, 5.5 x 8 inches, $13 ppd. USA and Canada. $15 for international orders. Write to Cherie Hunter Day, P.O. Box 910562, San Diego, CA 92191.

Because of a Seagull by Gilles Fabre. The Fishing Cat Press. Perfect bound, 8.5 x 5.5, unnumbered pages, two haiku per page. Includes a CD with a French translation of the poems. 2005. ISBN:0-9551071-0-5.

Gatherings: A Haiku Anthology edited by Stanford M. Forrester. Bottle Rockets Book #13. Published by Bottle Rockets Press, P.O. Box 189Windsor, Connecticut, 06095. Flat spine, color cover, 5 x 6.5 inches, 78 pages, ISBN:978-0-9792257-2-7, $14.

Opening the Pods by Silva Ley. Translation from the Dutch Ontbolstering by Silva Ley. AHA Online Book, 2008.

In the Company of Crows: Haiku and Tanka Between the Tides by Carole MacRury. Edited by Cathy Drinkwater Better. Black Cat Press, Eldersburg, Maryland: 2008. Perfect bound, 140 pages, sumi-e by Ion Codrescu, author and artist notes, $18.

The Japanese Universe for the 21st Century: Japanese / English Japanese Haiku 2008, edited and published by the Modern Haiku Association (Gendai Haiku Kyokai) Tokyo, Japan. Perfect bound, dust jacket, 220 pages, indexed, bilingual with kanji and romaji for each poem. Translation of haiku by David Burleigh and prose by Richard Wilson ISBN:978-4-8161-0712-2, $25.

Haiga 1998 2008 Japan Collection by Emile Molhuysen. Binder bound, 8 x 12, unnumbered pages, with a CD included. E-mail for price and shipping.Website.

Haiku, Haibun, Haiga De la un poem la altul by Valentin Nicolitov. Societatea Scritorilor Militari, Bucuresti: 2008. Translated from Romanian into English and French. Flat-spine, 5.5 x 8 inches, 142 pages. ISBN:978-973-8941-34-2.

Floating Here and There written and translated by Ikuyo Okamoto. Kadokawa Shoten. ISBN:978-4-04-52039-5, US$15. Perfect bound, 4 x 7, 130 pages, bilingual with poems in kanji and English.

So the Elders Say Tanka Sequence by Carol Purington and Larry Kimmel. Folded 8 x 11 inches single sheet with color photos. Winfred Press, 2008

The Irresistible Hudson: A Haiku Tribute Based on Yiddish Poetry by Martin Wasserman. Honors Press, Adirondack Community College, State University of New York, 640 Bay Road, Queensbury, New York, 12804. Flat-spine, 28 pages, 5.5 x 8 inches. No Price, no web access given.

The Tanka Prose Anthology, edited by Jeffrey Woodward. Modern English Tanka Press, PO Box 43717, Baltimore, MD 21236 USA. Perfect bound, 6 x 9, 175 pages, biographies of contributors, bibliography, $12.95. Available through Lulu.com

Tanka written and translated by Geert Verbeke. Cover photo by Jenny Ovaere taken in Nagarkot Nepal. Printed by Cybernit.net, in Govindpur Colony, Allahabad, India. 2008. Perfect bound with color cover, 5.25 x 8.5 inches, 48 pages, with two poems per page in Dutch and English. Contact Geert Verbeke for purchase information. He often will do a simple trade; send him your book and he will send you his.

NOTES OF OTHER BOOKS AND REVIEWS

Curtis Dunlap has written a book review of Basho The Complete Haiku that you can find at: http://tobaccoroadpoet.blogspot.com/2009/01/basho-complete-haiku-book-review .html

Modern Haiga is an annual journal both print and digital dedicated to publishing and promoting fine modern graphic poetry, especially but not limited to, haiku, senryu, tanka, cinquain, cinqku, crystallines, cherita, and sijo. Many writers and artists around the world have generously shared their work in Modern Haiga.

Jack Fruit Moon, haiku and tanka by Robert D. Wilson, Published by Modern English Tanka Press. Available from Lulu.com, from major booksellers, and from the publisher. Complete information and a mail or email order form are available online. Trade paperback price: $16.95 USD. ISBN 978-0-9817691-4-1. 204 pages, 6.00″ x 9.00″, perfect binding, 60# cream interior paper, black and white interior ink, 100# exterior paper, full-color exterior ink.

LETTERS from

Curtis Dunlap, Christopher Herold, Salvatore Buttaci, Mike Montreuil, Renee Owen, Sheri Files, Linda Papanicolaou, . Rabbi Neil Fleischmann, Robin Bownes, Allison Millcock, Dick Pettit, Patrick M. Pilarski

CONTESTS AND CONTEST RESULTS

ukiaHaiku festival, Kikakuza Haibun Contest – English Section, Pinewood Haiku Contest

ADVERTISEMENTS OF MAGAZINES, BOOKS, AND WEBSITES

White Lotus A Journal of Short Asian Verse & Haiga, Wollumbin Haiku Workshop, Rusty Tea Kettle, Proposing to the Woman in the Rear View Mirror by James Tipton, The Heron’s Nest, The Twelve Days Of Christmas by Gillina Cox, Allison Millcock’s blog @ http://millcock. blogspot.com/ ,Curtis Dunlap’s blog, Modern Haibun & Tanka Prose, bottle rockets press, MET 10, Winter 2008, has been published in print and digital editions. Call for Submissions Modern English Tanka. Issue Vol. 3, No. 3. Spring 2009, Pat Lichen’s new website, Gene Doty’s The Ghazal Page. Ghazal blog.Marlene Mountain, December of CHO issue, website of Isidro Iturat, Sketchbook, Simply Haiku, John Barlow Editor, Snapshot Press, The new issue of Shamrock Haiku Journal.

ARTICLES

A TALE OF A FESTIVAL by Kate Marianchild; THE FIRST ENGLISH-LANGUAGE HAIKU ANTHOLOGY AN INTERVIEW WITH MARGOT BOLLOCK by Jane Reichhold & Margot Bollock; THE REVOLUTION IS SETTING THE CHILDREN OUT ON THE RAPIDS WHERE THEY KEEP FLOATING ALONG by Werner Reichhold

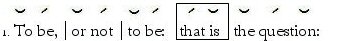

The Annotated “To be or not to be”

As far as this soliloquy goes, there’s a surplus of good online analysis. And if you’re a student or a reader then you probably have a book that already provides first-rate annotation. The only annotation I haven’t found (which is probably deemed unnecessary by most) is an analysis of the blank verse – a scansion – along with a look at its rhetorical structure. So, the post mostly reflects my own interests and observations – and isn’t meant to be a comprehensive analysis. If any of the symbols or terminology are unfamiliar to you check out my posts on the basics of Iambic Pentameter & scansion. Without further ado, here it is. (I’ve numbered the lines for the convenience of referencing.)

As far as this soliloquy goes, there’s a surplus of good online analysis. And if you’re a student or a reader then you probably have a book that already provides first-rate annotation. The only annotation I haven’t found (which is probably deemed unnecessary by most) is an analysis of the blank verse – a scansion – along with a look at its rhetorical structure. So, the post mostly reflects my own interests and observations – and isn’t meant to be a comprehensive analysis. If any of the symbols or terminology are unfamiliar to you check out my posts on the basics of Iambic Pentameter & scansion. Without further ado, here it is. (I’ve numbered the lines for the convenience of referencing.)

1.) The first line, in a single line, sums up the entirety of the soliloquy – as though Shakespeare were providing crib notes to his own soliloquy. There’s a reason. He wants to cleanly and clearly establish in the playgoers mind the subject of the speech. There will be no working out or self-discovery. Shakespeare is effectively communicating to us some of the reason for Hamlet’s hesitancy. The speech, in effect, is the reverse of the Shakespearean Sonnet that saves its epigrammatic summing up for the last line. The Shakespearean Sonnet, as Shakespeare writes it, is the working out of a proposition or conflict that finds a kind of solution in the epigrammatic couplet at its close.

Metrically, the first line is possibly one of the most interesting and potentially ambiguous in the entire speech. I chose to scan the line as follows:

- To be |or not |to be: |that is |the question

But if you google around, you may find the line more frequently scanned as follows:

- To be |or not |to be: |that is|the question

First to the disclaimer: There is no one way to scan a line but, as with performing music, there are historically informed ways to scan a poem. Shakespeare was writing within a tradition, was a genius, and knew perfectly well when he was or wasn’t varying from the Iambic Pentameter pattern of blank verse. To assume less is to assume that he was mindlessly writing a verse he either didn’t or couldn’t comprehend.

An actor has some latitude in how he or she wants to perform a line, but choosing to ignore the meter is akin to ignoring slurs or other markings composers provide in musical scores. Putting the emphasis on that subtly alters the meaning of the line. It sounds as though Hamlet were looking for the question, the conundrum, and once he has found it he says: Ah ha! That is the question. And this is how most modern readers read the line.

By putting the emphasis on is, in keeping with the Iambic Meter, the meaning of the line takes on a more subtle hue – as if Hamlet knew the question all along. He says: That is the question, isn’t it. The one question, the only question, ultimately, that everyone must answer. There’s a feeling of resignation and, perhaps, self-conscious humor in this metrical reading.

That said, William Baer, in his book Writing Metrical Poetry, typifies arguments in favor of emphasizing  that. He writes: “After the heavy caesura of the colon, Shakespeare alters the dominant meter of his line by emphasizing the word that over the subsequent word is. ” (Page 14)

that. He writes: “After the heavy caesura of the colon, Shakespeare alters the dominant meter of his line by emphasizing the word that over the subsequent word is. ” (Page 14)

How does Baer know Shakespeare’s intentions? How does he know that Shakespeare, in this one instance, means to subvert the iambic meter? He doesn’t tell us. All he says is that “most readers will substitute a trochee after the first three iambs” – which hardly justifies the reading. Baer’s argument seems to be: Most modern readers will read the foot as a trochee, therefore Shakespeare must have written it as a trochee.

The word anachronistic comes to mind.

If one wants to emphasize that for interpretive reasons, who am I to quarrel? But the closest we have to Shakespeare’s opinion is what he wrote and the meter he wrote in. And that meter tells us that is receives the emphasis, not that.

Note: Baer later mis-attributes the witch’s chant in Macbeth (Page 25) as being by Shakespeare- an addition which most Shakespearean scholars recognize as being by Middleton. Not a big deal, but this stuff interests me.

Anyway, I prefer an iambic reading knowing that not everyone will.

The line closes with a feminine ending in the fifth foot. For this reason, the line isn’t an Iambic Pentameter line but a variant within the larger Iambic Pentameter pattern. Compare the blank verse of Shakespeare to that of many modern Formalist poets. Shakespeare is frequently far more flexible but, importantly, flexes the pattern without disrupting it. Finding a balance between a too-strict adherence to a metrical line and too-liberal variation from it is, among modern poets, devoutly to be wished for. But modern poets are hardly unique in this respect, compare this to Middleton’s blank verse (a contemporary who collaborated with Shakespeare.) Middleton stretches blank verse to such a degree that the overall pattern begins to dissolve. He is too liberal with his variants.

2-3.) Both lines close with a feminine ending. They elaborate on the first part of the question- To be. The elegance & genius of Shakespeare’s thought and method of working out ideas is beautifully demonstrated in this speech. The speech as a whole stands as a lovely example of Prolepsis or Propositio – when a speaker or writer makes a general statement, then particularizes it. Interestingly, I was going to provide a link for a definition of Prolepsis but every online source I’ve found (including Wikipedia and Brittanica!) fails to get it completely right. (So much for on-line research.)

OK. Digression. (And this will only appeal to linguists like me.) Here’s a typical definition of Prolepsis as found online:

- A figure of speech in which a future event is referred to in anticipation.

This isn’t wrong, but it’s not the whole story. Whipping out my trusty Handbook to Sixteenth Century Rhetoric, we find the following:

- Propositio

- also known as prolepsis (not to be confused with praesumptio)

- Susenbrotus ( 28 )

Scheme. A general statement which preceedes the division of this general proposition into parts.

Praesumptio is the other meaning of Prolepsis, which is what you will find on-line. So, I guess you heard it here, and online, first. Prolepsis has two meanings.

Anyway, Shakespeare takes the general To be, and particularizes it, writing : Is it nobler “to be”, and to suffer the “slings and arrows” of life? The method of argumentation, known as a Topic of Invention, was drilled into Elizabethan school children from day one. All educated men in Shakespeare’s day were also highly trained rhetoricians – even if the vast majority forgot most of it. Shakespeare’s method of writing and thought didn’t come out of the blue. His habit of thought represents the education he and all his fellows received at grammar school.

4-5.) These two lines also close with feminine endings. Shakespeare, unlike earlier Renaissance dramatists, isn’t troubled by four such variants in a row. They elaborate on the second part of the of the question – not to be. Or is it better, Hamlet asks, to take arms and by opposing our troubles, end both them and ourselves? Is it better not to be?

6-9.) Up to this point, there has been a perfect symmetry in Shakespeare’s Prolepsis. He has particularized both to be and not to be. Now, his disquisition takes another turn. Shakespeare particularizes not to be (death) as being possibly both a dreamless sleep (lines 6 through 9) or a dream-filled sleep (lines 10 through 12). So, if I were to make a flowchart, it would look like this:

In line 7, natural should be elided to read nat‘ral, otherwise the fifth foot will be an anapest. While some metrists insist that Shakespeare wrote numerous anapests, I don’t buy their arguments. Anapests were generally frowned on. Secondly, such metrists need to explain why anapests, such as those above, are nearly always “loose iambs”, as Frost called them – meaning that elipsis, synaloepha or syncope could easily make the given foot Iambic. Hard-core, incontestable anapests are actually very difficulty to find in Shakespeare’s verse. They are mitigated by elision, syncope or midline pauses (epic caesuras).

10-13.) Shakespeare now particularizes “not to be” (or death) as, perhaps, a dream filled state. This is the counterpart to lines 6-9 in this, so far, exquisitely balanced disquisition. For in that sleep of death what dreams may come – he asks.

14-27.) At this point, Shakespeare could have enumerated some of the fearful dreams attending death – a Dante-esque descent into fearful presentiments. But Shakespeare was ever the pragmatist – his feet firmly planted in the realities of life. He took a different tact. He offers us the penury, suffering and the daily indignities of life. We suffer them, despite their agonies, fearing worse from death. We bear the whips and scorns of time (aging and its indignities), the wrongs of oppressors (life under tyranny), the law’s delay, the spurns of office. Who, he asks, would suffer these indignities when he could end it all with an unsheathed dagger (a bare bodkin) to his heart or throat? – if it weren’t for the fear of what might greet them upon death? Those dreams must be horrible! And he leaves it to us to imagine them – our own private hells – rather than describe that hell himself – Shakespeare’s genius at work.

Line 15 presents us with a rhetorical figure Hendiadys. Interestingly, it’s in Hamlet that Shakespeare uses this figure the most:

- For who would bear the whips and scorns of time?

The figure denotes the use of two nouns for a noun and its modifier. It’s a powerfully poetic technique in the right hands, and one that is almost unique to Shakespeare. Few poets were ever, afterward, as rhetorically inventive, adventurous or thorough in their understanding and use of rhetoric. It’s part and parcel of why we consider Shakespeare, not just a dramatic genius, but a poetic genius. He unified the arts of language into an expressive poetry that has never been equaled.

Line 16 presents us with some metrical niceties. I’ve chosen to use synaloepha to read The oppres|sor’s wrong as (Th’op)pres|sor’s wrong. I’m not wedded to that reading. One might also consider it a double onset or anacrusis (as some prefer to call it) – two unstressed syllables followed by a stressed syllable in the first foot. Interestingly, metrists have historically preferred to consider this anapest a special variant and so don’t refer to it as an anapest. As a practical matter (considering how the line is likely to be spoken by an actor) I suspect that the first foot will sound more like an Iamb or a loose Iamb – which is why I scanned it the way I did. Line 16 closes with the word contumely. I think that nearly all modern readers would read this as con-tume-ly. A glance at Webster’s, however, reveals that the word can also be pronounced con-tume-ly. The difference probably reflects changes in pronunciation over time. In this case, it’s the meter that reveals this to us. An incontestable trochee in the final foot is extremely rare in Shakespeare, as with all poets during that time. If you’re ever tempted to read a final foot as trochaic, go look up the word in a good dictionary.

In line 22 the under, in the third foot (under |a wear|y life), is nicely underscored by being a trochaic variant.

In line 25 the fourth foot echoes line 22 with the trochaic puzzles. This is a nice touch and makes me wonder if the reversal of the iambic foot with under and puzzles wasn’t deliberate – effectively puzzling the meter or, in the former, echoing the toil of a “weary life” and the “reversal” of expectations. But it’s also possible to read too much into these variants.

By my count, there are only 6 Iambic Pentameter lines out 13 or so lines (lines 14-27). The rest of the lines are disrupted by variant feet. That means that less than 50% of Shakespeare’s lines, out of this tiny sampling, are Iambic Pentameter. The Blank Verse of Shakespeare (an ostensibly Iambic Pentameter verse form) is far more flexible and varied than one might, at first, expect.

28-33.) These lines mark the true close of the soliloquy. “The native hue of resolution/Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought.” Fear of the dreams that may inhabit death makes cowards of us all. Some modern readers might be tempted to read line 28 as follows:

- Thus con|science does |make co|wards of |us all

But the Iambic Pentameter pattern encourages us (when we can) to read feet as Iambic. In this case it makes more sense to emphasize does rather than make.

- Thus con|science does |make co|wards of |us all

One thing worth noticing, and it’s my very favorite poetic technique and one that has been all but forgotten by modern poets, is anthimeria – the substitution of one part of speech for another.

The native hue of resolution

The native hue of resolution

Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought

Sickly is an adverb that Shakespeare uses as a verb. In Sister Miriam Jospeh’s book, Shakespeare’s Use of the Arts of Language, she writes: “More than any other figure of grammar, it gives vitality and power to Shakespeare’s language, through its packed meaning, liveliness and stir. ” She herself goes on to quote another writer, Alfred Hart:

Most Elizabethan and Jacobean authors use nouns freely as verbs, but they are not very venturesome…. The last plays of Shakespeare teem with daringly brilliant metaphors due solely to this use of nouns and adjectives as verbs…. they add vigor, vividness and imagination to the verse… almost every play affords examples of such happy valiancy of phrase.

Finally, notice the imagistic and syntactic parallelism in “the native hue of resolution” and “the pale cast of thought”. It’s a nice poetic touch that adds emphasis to Shakespeare’s closing argument – our fears dissuade us from enterprises “of great pith and moment”.

Interestingly, even as Hamlet’s dithering ends, he never truly decides whether “to be or not to be”.

If this has been helpful, let me know.

January 22 2009 – a field at midnight

January 20 2009 – old glove

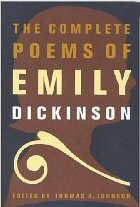

Emily Dickinson: Iambic Meter & Rhyme

Emily Dickinson possessed a genius for figurative language and thought. Whenever I read her, I’m left with the impression of a woman who was impish, insightful, impatient, passionate and confident of her own genius. Some scholars portray her as being a revolutionary who rejected (with a capital R) the stock forms and meters of her day.

Emily Dickinson possessed a genius for figurative language and thought. Whenever I read her, I’m left with the impression of a woman who was impish, insightful, impatient, passionate and confident of her own genius. Some scholars portray her as being a revolutionary who rejected (with a capital R) the stock forms and meters of her day.

My own view is that Dickinson didn’t exactly “reject” the forms and meter. She wasn’t out to be a revolutionary. She was impish and brilliant. Like Shakespeare, she delighted in subverting conventions and turning expectations upside down.This was part and parcel of her expressive medium. She exploited the conventions and expectations of the day, she didn’t reject them.

The idea that she was a revolutionary rejecting the tired prerequisites of form and meter certainly flatters the vanity of contemporary free verse proponents (poets and critics) but I don’t find it a convincing characterization. The irony is that if she were writing today, just as she wrote then, her poetry would probably be just as rejected by a generation steeped in the tired expectations and conventions of free verse.

The common meters of the hymn and ballad simply and perfectly suited her expressive genius. Chopin didn’t “reject” symphonies, Operas, Oratorios, Concertos, or Chamber Music, etc… his genius was for the piano. Similarly, Dickinson’s genius found a congenial outlet in the short, succinct stanzas of common meter.

The fact that she was a woman and her refusal to conform to the conventions of the day made recognition difficult (I sympathize with that). My read is that Dickinson didn’t have the patience for pursuing fame. She wanted to write poetry just the way she wanted and if fame mitigated that, then fame be damned. She effectively secluded herself and poured forth poems with a profligacy bordering on hypographia. If you want a fairly succinct on-line biography of Dickinson, I enjoyed Barnes & Noble’s SparkNotes.

The Meters of Emily Dickinson

Dickinson used various hymn and ballad meters.

Searching on-line, there seems to be some confusion of terms or at the least their usage seems confusing to me. So, to try to make sense of it, I’ve done up a meter tree.

The term Hymn Meter embraces many of the meters in which Dickinson wrote her poems and the tree above represents only the basic four types.

If the symbols used in this tree don’t make sense to you, visit my post on Iambic Pentameter (Basics). If they do make sense to you, then you will notice that there are no Iambic Pentameter lines in any of the Hymn Meters. They either alternate between Iambic Tetrameter and Iambic Trimeter or are wholly in one or the other line length. This is why Dickinson never wrote Iambic Pentameter. The meter wasn’t part of the pallet.

Common Meter (an iambic subset of Hymn Meter and most common) is the meter of Amazing Grace, and Christmas Carol.

And then there is Ballad Meter – which is a variant of Hymn Meter.

I’ve noticed that some on-line sites conflate Hymn Meter and Ballad Meter. But there is a difference. Ballad Meter is less formal and more conversational in tone than Hymn Meter, and Ballad Meter isn’t as metrically strict, meaning that not all of its feet may be iambic. The best example I have found is the theme song to Gilligan’s Island:

Obviously the tone is conversational but, more importantly, notice the anapests. The stanza has the same number of feet as Common Meter, but the feet themselves vary from the iambic regularity of Common Meter. Also notice the rhyme scheme. Only the second & fourth line rhyme. Common Meter requires a regular ABAB rhyme scheme. The tone, the rhyme scheme, and the varied meter distinguish Ballad Meter from Common Meter.

For the sake of thoroughness, the following gives an idea of the many variations on the four basic categories of Hymn meter. Click on the image if you want to visit the website from which the image comes (hopefully link rot won’t set it). Examples of the various meters are provided there.

If you look at the table above, you will notice that many of the hymn and ballad meters don’t even have names, they are simply referred to by the number of syllables in each line. Explore the site from which this table is drawn. It’s an excellent resource if you want to familiarize yourself with the various hymn and ballad meters Dickinson would have heard and been familiar with – and which she herself used. Note the Common Particular Meter, Short Particular Meter and Long Particular Meter at the top right. These names reflect the number of syllables per line you will frequently find in Dickinson’s poetry. Following is an example of Common Particular Meter. The first stanza comes from around 1830 – by J. Leavitte, the year of Dickinson’s Birth. This stuff was in the air. The second example is the first stanza from Dickinson’s poem numbered 313. The two columns on the right represent, first, the number of syllables per line and, second, the rhyme scheme.

Short Particular Meter is the reverse of this. That is, its syllable count is as follows: 6,6,8,6,6,8 – the rhyme scheme may vary. Long Particular Meter is 8,8,8,8,8,8 – Iambic Tetrameter through and through – the rhyme schemes may vary ABABCC, AABCCB, etc…

The purpose of all this is to demonstrate the many metrical patterns Dickinson was exposed to – most likely during church services. The singing of hymns, by the way, was not always a feature of Christian worship. It was Isaac Watts, during the late 17th Century, who wedded the meter of Folk Song and Ballad to scripture. An example of a hymn by Watts, written in common meter, would be Hymn 105, which begins (I’ve divided the first stanza into feet):

Nor eye |hath seen, |nor ear |hath heard,

Nor sense |nor rea|son known,

What joys |the Fa|ther hath |prepared

For those |that love |the Son.

But the good Spirit of the Lord

Reveals a heav’n to come;

The beams of glory in his word

Allure and guide us home.

Though Watts’ creation of hymns based on scripture were highly controversial, rejected by some churches and  adopted by others, one of the church’s that fully adopted Watts’ hymns was the The First Church of Amherst, Massachusetts, where Dickinson from girlhood on, worshiped. She would have been repeatedly exposed to Samuel Worcester’s edition of Watts’s hymns, The Psalms and Spiritual Songs where the variety of hymn forms were spelled out and demonstrated. While scholars credit Dickinson as the first to use slant rhyme to full advantage, Watts himself was no stranger to slant rhyme, as can be seen in the example above. In fact, many of Dickinson’s “innovations” were culled from prior examples. Domhnall Mitchell, in the notes of his book Measures of Possiblity emphasizes the cornucopia of hymn meters she would have been exposed to:

adopted by others, one of the church’s that fully adopted Watts’ hymns was the The First Church of Amherst, Massachusetts, where Dickinson from girlhood on, worshiped. She would have been repeatedly exposed to Samuel Worcester’s edition of Watts’s hymns, The Psalms and Spiritual Songs where the variety of hymn forms were spelled out and demonstrated. While scholars credit Dickinson as the first to use slant rhyme to full advantage, Watts himself was no stranger to slant rhyme, as can be seen in the example above. In fact, many of Dickinson’s “innovations” were culled from prior examples. Domhnall Mitchell, in the notes of his book Measures of Possiblity emphasizes the cornucopia of hymn meters she would have been exposed to:

One more variation on ballad meter would be fourteeners. Fourteeners essentially combine the Iambic Tetrameter and Trimeter alternation into one line. The Yellow Rose of Texas would be an example (and is a tune to which many of Dickinson’s poems can be sung).

According to my edition of Dickinson’s poems, edited by Thomas H. Johnson, these are the first four lines (the poem is much longer) of the first poem Emily Dickinson wrote. Examples of the form can be found as far back as George Gascoigne – a 16th Century English Poet who preceded Shakespeare. If one divides the lines up, one finds the ballad meter hidden within:

According to my edition of Dickinson’s poems, edited by Thomas H. Johnson, these are the first four lines (the poem is much longer) of the first poem Emily Dickinson wrote. Examples of the form can be found as far back as George Gascoigne – a 16th Century English Poet who preceded Shakespeare. If one divides the lines up, one finds the ballad meter hidden within:

Oh the Earth was made for lovers

for damsel, and hopeless swain

For sighing, and gentle whispering,

and unity made of twain

All things do go a courting

in earth, or sea, or air,

God hath made nothing single

but thee in His world so fair!

How to Identify the Meter

The thing to remember is that although Dickinson wrote no Iambic Pentameter, Hymn Meters are all Iambic and Ballad Meters vary not in the number of metrical feet but in the kind of foot. Instead of Iambs, Dickinson may substitue an anapestic foot or a dactyllic foot.

So, if you’re out to find out what meter Dickinson used for a given poem. Here’s the method I would use. First I would count the syllables in each line. In the Dickinson’s famous poem above, all the stanzas but one could either be Common Meter or Ballad Meter. Both these meters share the same 8,6,8,6 syllabic line count – Iambic Tetrameter alternating with Iambic Trimeter. (See the Hymn Meter Tree.)

Next, I would check the rhyme scheme. For simplicity’s sake, I labeled all the words which weren’t rhyming, as X. If the one syllabically varying verse didn’t suggest ballad meter, then the rhyme scheme certainly would. This isn’t Common Meter. This is Ballad Meter. Common Meter keeps a much stricter rhyme scheme. The second stanza’s rhyme, away/civility is an eye rhyme. The third stanza appears to dispense with rhyme altogether although I suppose that one should, for the sake of propriety, consider ring/run a consonant rhyme. It’s borderline – even by modern day standards. Chill/tulle would be a slant rhyme. The final rhyme, day/eternity would be another eye rhyme.

It occurs to me add a note on rhyming, since Dickinson used a variety of rhymes (more concerned with the perfect word than the perfect rhyme). This table is inspired by a Glossary of Rhymes by Alberto Rios with some additions of my own. I’ve altered it with examples drawn from Dickinson’s own poetry – as far as possible. The poem’s number is listed first followed by the rhymes. The numbering is based on The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson edited by Thomas H. Johnson.

![]()

RHYMES DEFINED BY NATURE OF SIMILARITY

perfect rhyme, true rhyme, full rhyme

- 1056 June/moon

imperfect rhyme, slant rhyme, half rhyme, approximate rhyme, near rhyme, off rhyme, oblique rhyme

- 756 prayer/despair

123 air/cigar

744 astir/door

augmented rhyme – A sort of extension of slant rhyme. A rhyme in which the rhyme is extended by a consonant.bray/brave grow/sown

- (Interestingly, this isn’t a type of rhyme Dickinson ever used, either because she was unaware of it or simply considered it a rhyme “too far”.)

diminished rhyme – This is the reverse of an augmented rhyme. brave/day blown/sow stained/rain

- (Again, this isn’t a technique Dickinson ever uses.)

unstressed rhyme – Rhymes which fall on the unstressed syllable (much less common in Dickinson).

- 345 very/sorry

1601 forgiven/hidden prison/heaven

eye rhyme – These generally reflect historical changes in pronunciation. Some poets (knowing that some of these older rhymes no longer rhyme) nevertheless continue to use them in the name of convention and convenience.

- 712 day/eternity (See Above)

94 among/along

311 Queen/been

580 prove/Love

identical “rhyme” – Which really isn’t a rhyme but is used as such.

- 1473

Pausing in Front of our Palsied Faces

Time compassion took –

Arks of Reprieve he offered us –

Ararats – we took –

- 130 partake/take

rich rhyme – Words or syllables that are Homonyms.

- 130 belief/leaf

assonant rhyme – When only the vowel sounds rhyme.

- 1348 Eyes/Paradise

consonant rhyme, para rhyme – When the consonants match.

- 744 heal/hell

889 hair/here

feminine para rhyme – A two syllable para rhyme or consonant rhyme.

scarce rhyme – Not really a true category, in my opinion, since there is no difference between a scarce rhyme and any other rhyme except that the words being rhymed have few options. But, since academia is all about hair-splitting, I looked and looked and found these:

- 738 guess/Rhinoceros (slant rhyme)

1440 Mortality/Fidelity (extended rhyme)

813 Girls/Curls (true rhyme)

macaronic rhyme – When words of different languages rhyme. (This one made me sweat. Dickinson’s world was her room, it seems, which doesn’t expose one to a lot of foreign languages. But I found one! As far as I know, the first one on the Internet, at least, to find it!)

- 313 see/me/Sabachthani (Google it if you’re curious.)

trailing rhyme – Where the first syllable of a two syllable word rhymes (or the first word of a two-word rhyme rhymes). ring/finger scout/doubter

- (These examples aren’t from Dickinson and I know of no examples in Dickinson but am game to be proved wrong.)

apocopated rhyme – The reverse of trailing rhyme. finger/ring doubter/scout.

- (Again, I know of no examples in Dickinson’s poetry.)

mosaique or composite rhyme – Rhymes constructed from more than one word. (Astronomical/solemn or comical.)

- (This also is a technique which Dickinson didn’t use.)

![]()

RHYMES DEFINED BY RELATION TO STRESS PATTERN

one syllable rhyme, masculine rhyme – The most common rhyme, which occurs on the final stressed syllable and is essentially the same as true or perfect rhyme.

- 313 shamed/blamed

259 out/doubt

light rhyme – Rhyming a stressed syllable with a secondary stress – one of Dickinson’s most favored rhyming techniques and found in the vast majority of her poems. This could be considered a subset of true or perfect rhyme.

- 904 chance/advance

416 espy/try

448 He/Poverty

extra-syllable rhyme, triple rhyme, multiple rhyme, extended rhyme, feminine rhyme – Rhyming on multiple syllables. (These are surprisingly difficult to find in Dickinson. Nearly all of her rhymes are monosyllabic or light rhymes.)

- 1440 Mortality/Fidelity

809 Immortality/Vitality

962 Tremendousness/Boundlessness

313 crucify/justify

wrenched rhyme – Rhyming a stressed syllable with an unstressed syllable (for all of Dickinson’s nonchalance concerning rhyme – wrenched rhyme is fairly hard to find.)

- 1021 predistined/Land

522 power/despair

![]()

RHYMES DEFINED BY POSITION IN THE LINE

end rhyme, terminal rhyme – All rhymes occur at line ends–the standard procedure.

- 904 chance/advance

1056 June/moon

initial rhyme, head rhyme – Alliteration or other rhymes at the beginning of a line.

- 311 To Stump, and Stack – and Stem –

- 283

Too small – to fear –

Too distant – to endear –

- 876

Entombed by whom, for what offense

internal rhyme – Rhyme within a line or passage, randomly or in some kind of pattern:

- 812

It waits upon the Lawn,

It shows the furthest Tree

Upon the furthest Slope you know

It almost speaks to you.

leonine rhyme, medial rhyme – Rhyme at the caesura and line end within a single line.

- (Dickinson’s shorter line lengths, almost exclusively tetrameter and trimeter lines, don’t lend themselves to leonine rhymes. I couldn’t find one. If anyone does, leave a comment and I will add it.)

caesural rhyme, interlaced rhyme – Rhymes that occur at the caesura and line end within a pair of lines–like an abab quatrain printed as two lines (this example is not from Dickinson but one provided by Rios at his webpage)

- Sweet is the treading of wine, and sweet the feet of the dove;

But a goodlier gift is thine than foam of the grapes or love.

Yea, is not even Apollo, with hair and harp-string of gold,

A bitter God to follow, a beautiful God to behold?

(Here too, Dickinson’s shorter lines lengths don’t lend themselves to this sort of rhyming. The only place I found hints of it were in her first poem.)

![]()

By Position in the Stanza or Verse Paragraph

crossed rhyme, alternating rhyme, interlocking rhyme – Rhyming in an ABAB pattern.

- (Any of Dickinson’s poems written in Common Meter would be Cross Rhyme.)

intermittent rhyme – Rhyming every other line, as in the standard ballad quatrain: xaxa.

- (Intermittent Rhyme is the pattern of Ballad Meter and reflects the majority of Dickinson’s poems.)

envelope rhyme, inserted rhyme – Rhyming ABBA.

- (The stanza from poem 313, see above, would be an example of envelope rhyme in Common Particular Meter.)

irregular rhyme – Rhyming that follows no fixed pattern (as in the pseudopindaric or irregular ode).

- (Many of Dickinson’s Poems seem without a definite rhyme scheme but the admitted obscurity of her rhymes – such as ring/run in the poem Because I could not stop for death – serve to obfuscate the sense and sound of a regular rhyme scheme. In fact, and for the most part, nearly all of Dickinson’s poems are of the ABXB pattern – the pattern of Ballad Meter . This assertion, of course, allows for a wide & liberal definition of “rhyme”. That said, poems like 1186, 1187 & 1255 appear to follow no fixed pattern although, in such short poems, establishing whether a pattern is regular or irregular is a dicey proposition.)

sporadic rhyme, occasional rhyme – Rhyming that occurs unpredictably in a poem with mostly unrhymed lines. Poem 312 appears to be such a poem.

thorn line – An un-rhymed line in a generally rhymed passage.

- (Again, if one allows for a liberal definition of rhyme, then thorn lines are not in Dickinson’s toolbox. But if one isn’t liberal, then they are everywhere.)

![]()

RHYME ACROSS WORD BOUNDARIES

broken rhyme – Rhyme using more than one word:

- 516 thro’ it/do it

(Rios also includes the following example at his website)

- Or rhyme in which one word is broken over the line end:

I caught this morning morning’s minion, king-

Dom of daylight’s dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon, in his riding

Of the rolling level underneath him steady air, and striding

High there, how he rung upon the rein of a wimpling wing…

(I can find no comparable example in Dickinson’s poetry.)

![]()

Getting back to identifying meter (in Dickinson’s Because I could not stop for death) the final method is to scan the poem. The pattern is thoroughly iambic. The only individual feet that might be considered anapestic variants are in the last stanza. I personally chose to elide cen-tu-ries so that it reads cent‘ries – a common practice in Dickinson’s day and easily typical of modern day pronunciation. In the last line, I read toward as a monosyllabic word. This would make the poem thoroughly iambic. If a reader really wanted to, though, he or she could read these feet as anapestic. In any case, the loose iambs, as Frost called them, argue for Ballad Meter rather than Common Meter – if not its overall conversational tone.

The poem demonstrates Dickinson’s refusal to be bound by form. She alters the rhyme, rhyme scheme and meter (as in the fourth stanza) to suit the demands of subject matter. This willingness, no doubt, disturbed her more conventional contemporaries. She knew what she wanted, though, and that wasn’t going to be altered by any formal demands. And if her long time “mentor”, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, had been a careful reader of her poems, he would have known that she wouldn’t be taking advice.

If I think of anything to add, I’ll add it.

If this post has been helpful, let me know.

Emily Dickinson & Iambic Pentameter

Emily Dickinson didn’t write Iambic Pentameter.

Now that I’ve exhaustively examined Dickinson and Iambic Pentameter, my next post will look at Dickinson’s use of Hymn Meter and Ballad Meter.

Vermont Plates

These are my real plates – current and on my car. The first thing I did when I moved back to Vermont was to get these – about 8 years ago. I was convinced the plates wouldn’t be available. But I suppose I was the only one in the entire state with enough hubris to order vanity plates with POET on them.

If you happen to be in Vermont and happen to see these plates. It’s me. I saw another set of Vermont plates, across the river, with WRITER on them. I was jealous! I should have gotten those too! – I said to myself. Good grief.

If you have literary vanity plates, send me a picture of them and I’ll put them on my blog with a link.

January 14 2009 – the red & orange snow

January 12, 2009 – cracked window