- Revised & improved April 12, 2009.

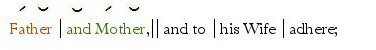

The Creation of Eve

Milton’s blank verse is exceedingly conservative and easy to scan. It’s a testament to Milton’s skill as a poet  that his beautiful language and careful phrasing triumphs over his monotonous meter – in many cases subtly disrupting it without violating it. It’s a miracle, really. (For an example of a poet who didn’t pull it off, read Spencer’s Fairy Queen.) It was as if the experimentation of the Elizabethans, let alone the Jacobeans, had never occurred. Milton came of age in an exceedingly conservative era- poetically. Meter, in those days, was as dominant then as free verse now, and as unadventurous. Just the fact that Milton wrote blank verse (when everyone else was writing heroic couplets) was an act of defiance.

that his beautiful language and careful phrasing triumphs over his monotonous meter – in many cases subtly disrupting it without violating it. It’s a miracle, really. (For an example of a poet who didn’t pull it off, read Spencer’s Fairy Queen.) It was as if the experimentation of the Elizabethans, let alone the Jacobeans, had never occurred. Milton came of age in an exceedingly conservative era- poetically. Meter, in those days, was as dominant then as free verse now, and as unadventurous. Just the fact that Milton wrote blank verse (when everyone else was writing heroic couplets) was an act of defiance.

Most of the trouble surrounding Milton and scansion (for modern readers) comes down to differences in pronunciation – some of it has to do with historical changes; and some, if you’re American, has to do with differences in British and American pronunciation (especially problematic when reading Chaucer).

I cooked up a table that, with its “scientific” terminology, gives you an idea of Milton’s metrical habits and preferences. I haven’t gone line by line to exhaustively prove the accuracy of my table, but I can assert, for example, that Milton (despite claims to the contrary) never wrote a trochee in the final foot. Here’s an extract, to that effect, from my review of M.L. Harvey’s Book Iambic Pentameter from Shakespeare to Browning: A Study in Generative Metrics (Studies in Comparative Literature):

A more egregious example of misreading, due to changes in habits of pronunciation and even to present day differences between the continents, comes when Mr. Harvey examines Milton. Words like “contest” and “blasphemous” and “surface” (all taken from Paradise Lost) were still accented on the second syllable. “Which of us beholds the bright surface.” (P.L. 6.472 MacMillan. Roy Flannagan Editor.) Mr. Harvey, offering an example of a “very rare `inverted foot’” (the credit for its recognition he gives to Robert Bridges) gives the following line: “Of Thrones and mighty Seraphim Prostrate (P.L. 6.841) In fact, Robert Bridges and Mr. Harvey are both mistaken in reading the fifth foot as inverted and one need not be a seventeenth century scholar to recognize it. Webster’s International Dictionary: Second Edition, in fact, provides the following pronunciation key. (pros [stressed] trat [unstressed]; formerly, and still by some. Esp. Brit., pros [unstressed] trat [stressed]). Any laboratory of Americans, nearly without fail, would also misread this line, and so the danger of overwhelming empirical evidence!

On to my table… Each division represents an equivalent foot in an Iambic Pentameter line.

The Scansion

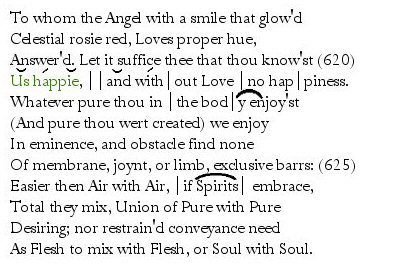

Here is one of my favorite passages, already alluded to in a previous post – Iambic Pentameter Variants – I. To simplify matters, I haven’t marked any of the Iambic feet , I’ve only marked variant feet or feet that, for one reason another, might be read incorrectly.

Elision

Elision, a standard practice in Milton’s day and more or less assumed whether marked or not, eliminates the vast majority of Milton’s “variant” feet.

Glorious, if treated as a three syllable word, would make the second foot Anapestic, not criminal, but if you can elide, you should.

This elision might make some metrists squirm. Given just how conservative metrical practice tended to be in Milton’s day, I would be inclined to elide these two vowels. Given how Milton can barely bring himself to so much as use a feminine ending in the final foot, I seriously doubt he expected readers to treat this foot as an anapest. My advice is to elide it.

The final example of elision, above, is the word Spirits. Interestingly, Milton seems to treat this word opportunistically. In line 466, for example, he treats spirits as a two syllable word. In other lines, throughout Paradise Lost and in the latter line, he treats the word as a monosyllabic word. This sort of inconsistency in pronunciation is found as far back as Chaucer, as with his pronunciation of the word sweete – sometimes one syllable, sometimes two. Such inconsistency is permitted once one has obtained a poetic license.

Reading with the Meter

Modern readers may sometimes be tempted to read as though they were reading prose. Sometimes, though, poets play the line against the meter, wanting us to emphasize certain words we might not otherwise. That’s the beauty of meter in poetry. Milton, as with all the great poets, was skilled at this sort of counterpoint:

![]()

In the line above, the modern reader might be tempted to stress the line as follows:

Mean, or in her summ’d up, in in her containd

This would be putting the emphasis on the words in. In free verse, ok, but not Iambic Pentameter and especially not with a metrically conservative poet like Milton. Milton wants us to put the emphasis on her. Maybe the line above doesn’t seem such a stretch? Try this one:

![]()

Any modern reader would put the emphasis on Bone and Flesh:

Bone of my Bone, Flesh of my Flesh, my Self

But they would be missing the point of Milton’s line – the closing my Self! That is, it’s not the Bone or Flesh that amazes Adam, it’s that the Bone and Flesh are of his Bone and of his Flesh. His Self! This contrapuntal exploitation of the meter is a master stroke and to miss it is to miss Milton’s genius. If it’s read in this light, stressing the prepositional of might not feel so strained or artificial.

Pentameter at all costs!

Milton’s obeisance to the demands of Iambic Pentameter aren’t always entirely successful.

![]()

This, to me, is a reach, but it’s probably what Milton intended and even how he pronounced it. Practice it with studied e-nunc-i-a-tion and the line may make a little more sense. An alternative is to read the line as Iambic Tetrameter.

![]()

Given Milton’s metrical squeamishness, I seriously doubt that, in the entirety of Paradise Lost, he decided, for just one moment, to write one Tetrameter line. There are other alternative Tetrameter readings, but they get uglier and uglier.

That said, ambiguities like these, along with the examples that follow, are what disrupt the seeming monotony of Milton’s meter. His use of them defines Milton’s skill as a poet. Roy Flannagan’s introduction to Paradise Lost (page 37) is worth quoting in this regard:

Milton writes lines of poetry that appear to be iambic pentameter if you count them regularly but really contain hidden reversed feet or elongated or truncated sounds that echo meaning and substance rather than a regular and hence monotonous beat. He builds his poetry on syllable count and on stress; William B. Hunter, following the analysis of Milton’s prosody by the poet Robert Bridges in 1921, counts lines that vary in the number of stresses from three all the way up to eight, but with the syllabic count remaining fixed almost always at ten (“The Sources” 198). Milton heavily favors ending his line on a masculine , accented syllable, with frequent enjambment or continuous rhythm from one line to the next… He avoids feminine feet or feet with final unstressed syllables at the ends of lines. He varies the caesura, or the definitive pause within the line, placing it more freely than any other dramatist or non-dramatic writer Hunter could locate (199). He controls elisions or the elided syllables in words most carefully, allowing the reader to choose between pronouncing a word like spirit as a monosyllable (and perhaps pronounced “sprite”) or disyllable, or Israel as a disyllable or trisyllable.

Extra Syllables: Milton’s Amphibrachs (Feminine Endings & Epic Caesuras)

The amphibrach is a metrical foot if three syllables – unstressed-stressed-unstressed. In poets prior to the 20th Century it is always associated with feminine endings or epic caesuras. In the passages above, Milton offers us two examples, one in the second foot (by far the norm) and one in the first foot.

This would be an epic caesura. The comma indicates a sort of midline break (a break in the syntactic sense or phrase). Amphibrach’s, at least in Milton, are always associated with this sort of syntactic pause or break. Epic Caesuras and Feminine Endings are easily the primary reason for extra syllables in Milton’s line. Anapests make up the rest, but they are far less frequent and can be frequently elided.

![]()

This would be a much rarer Epic Caesura in the first foot. Notice, once again, that the amphibrachic foot occurs with a syntactic break, the comma.

Differences in Pronunciation

If you just can’t make sense of the metrical flow, it might be because you aren’t pronouncing the words the same way Milton and his peers did.

![]()

Most modern readers would probably pronounce discourse and dis’course. However, in Milton’s day and among some modern British, it was and is pronounced discourse’.

![]()

This one is trickier. In modern English, we pronounce attribute as att’ribute when used as a noun and attri’bute when used as a verb. Milton, in a rather Elizabethan twist, is using attributing in its nominal sense, rather than verbal sense. He therefore keeps the nominal pronunciation: att’tributing.

This one is trickier. In modern English, we pronounce attribute as att’ribute when used as a noun and attri’bute when used as a verb. Milton, in a rather Elizabethan twist, is using attributing in its nominal sense, rather than verbal sense. He therefore keeps the nominal pronunciation: att’tributing.

The arch-Angel says to Adam, as concerns Eve:

Dismiss not her…by attributing overmuch to things Less excellent…

It’s phenomenally good marital advice. In other words. Don’t dismiss her by just tallying up her negative attributes, to the exclusion of her positive attributes. There is more to any friendship, relationship, or marriage than the negative. Think on the positive.

Metrical Ambiguity

Some of Milton’s metrical feet are simply ambiguous – effectively breaking the monotony of the meter. In the example below, one could read the first foot as trochaic or as Iambic:

|Led by|

or

|Led by|?

I chose a trochaic foot – the first option. If this foot had been in the fifth foot (or the last foot of the line) I would have read it as Iambic. Milton doesn’t write trochaic feet in the fifth foot. In the first foot, however, trochaic feet aren’t uncommon and in this instant it seems to make sense. I don’t sense that there’s any crucial meaning lost by de-emphasizing by. Perhaps the best answer, in cases of metrical ambiguity, is to consider at what point in the line the ambiguity is occuring.

Similarly, I read the following line as having a spondee in the fourth foot:

![]()

One could also read it as trochaic or iambic. Iambic, given the metrical practice of the day, is far more likely than a trochaic foot – especially, given Milton’s practice, this close to the final foot. I scanned the foot as spondaic. Spondaic feet, in Milton’s day, were considered the least disruptive variant foot and so were acceptable at just about any point of the line.

My Favorite Passages

The passages excerpted above just about cover every metrical exigency you will run into in reading Milton. The other reason I chose them is because they’re, well, juicy. I love them. I especially like the following lines for their sense of humor (and, yes, Milton does have a sense of humor).

What boyfriend or husband hasn’t had this experience? No matter how rational we think we are, all our intellectual bravado crumbles to folly – men are from Mars, women are from Venus.

Did Adam & Eve have sex? Why, yes, says Milton, but it wasn’t pornographic. That came after the fall:

Lastly, and most importantly, is there sex in heaven (or do we have to go to hell for that)? Milton gives us the answer:

If you enjoyed this post and found it helpful, comment! Let me know. And if you have further questions or corrections, I appreciate those too.