The first time I read the Earthsea Trilogy, I was fifteen years old and on the outer banks of North Carolina. Short of the Azores, that might have been the best place to read the original trilogy—on an island with the Atlantic washing the sands outside my door. At that point, that was all that Le Guin had written of Earthsea. I was a fifteen year old reading a YA series (as Le Guin herself describes it) about a 19 year old Wizard (and later a younger—16 or 17 year old?—Tenar). Le Guin doesn’t commit, simply saying that Tenar (as central to the series as the Wizard Ged) was ‘not even that old’. In a sense, I was the perfect age, reading a fantasy series written for me.

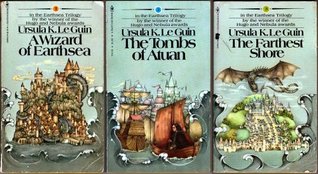

I still have the books that I read over 40 years ago—the same issue as the books above.

Close to ten years after I had read the original trilogy, Le Guin published Tehanu (for Le Guin, it was 18 years). Tehanu is a horse of a different color. Firstly, Le Guin decided the book wasn’t going to be a YA novel, but one for adults and with adult themes and secondly, she set out to right the perception that her initial trilogy (if it wasn’t misogynist) took a dim view of women in an uncritically patriarchal fantasy world. The men were wizards of great schooling, power and wisdom while women were, at best, smelly village witches living in dank, smelly little houses who pedaled deceit and ignorance. “There is a saying on Gont, Weak as woman’s magic, and there is another saying, Wicked as woman’s magic,” Le Guin wrote.

Le Guin changed all that with Tehanu. She would write:

[A woman’s magic] goes down deep. It’s all roots. It’s like an old blackberry thicket. And a wizard’s power’s like a fir tree, maybe, great and tall and grand, but it’ll blow right down in a storm. Nothing kills a blackberry bramble. [Tehanu 100]

This is spoken by the Witch Moss (who was still smelly) but whose mythology in the series, as a whole, undergoes a considerable transformation. This revision of women’s place in the Earthsea universe was beautifully written about in a paper called Witches, Wives and Dragons: The Evolution of the Women in Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea—An OverviewUrsula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea—An Overview.

The point I would make, in regards to this, is that to read Earthsea as a unified vision, in the same manner as Lord of the Rings, is going to leave the reader disappointed. There are any number of critiques by readers bemoaning the “feminist revision” of the initial three books—the loss of the archetypal hierarchies easily recognizable from the fairy tales of the past thousand years. But if you’re going to read Earthsea this way, then you’ll likely be disappointed, wondering why she ruined the first three novels.

What makes Earthsea fascinating is to see how an author revisits a world that was ostensibly complete. Le Guin probably never planned to write another Earthsea book after completing the initial trilogy. Normally, the author drops hints and clues as to what’s to come. This propels the reader forward. Plot threads need to be tied up. But Le Guin tied up all her plot threads. Ged had lost his power. Like King Arthur, he was carried off into the mists of legend.

What makes the latter three books fascinating is to see how an author re-enters her own world, and radically transforms it. She can’t rewrite. The initial books are done and written, and yet she has to make the radical revision feel organic—as if the themes of the latter books were there, all along. Her solution is to make their very “completeness” a central problem. In this case, she treats their completeness as an artifact of Earthsea’s patriarchal bias. They only seem complete because it was the male perspective, in a sense, that was telling the story. It’s a neat feat, since she, Le Guin, was the author of the first three books, but the latter three books treat this perspective as the “evil” that threatens the latter books.

Melanie Rawls, the author of the paper cited above, puts it this way:

The “author” of the first three books did not know why women’s magic was weak or wicked, or she gives no explanation in the books, presenting that information as everyday fact. The “author” was unaware of the history of the founding of Roke. The author of the first three books seems to know the nature of dragons, and it is a nature familiar to us from our western myths, epics and folktales. In these books, dragons are indisputably male.

And then later:

The latter three books, however, demonstrate how much the earlier “author” does not know about dragons. The dragons of the last three books are female: the Woman of Kemay, Tehanu, Orm Irian.

It’s in that sense, in my opinion, that Earthsea should be read, as a fascinating and archetypal story of the author’s inner journey, her revision of self (perhaps redemption). You’re reading the work of an author who has turned her inner journey into an archetypal fantasy novel. That said, it’s a curious thing (and I speculate) but the author Le Guin seems to favor men over women. Even when she expresses a “feminist” critique of the first three novels, one gets the sense that she continues to adore her male characters (which is why I find some of the criticism leveled against her latter books—by readers who resent the intrusion of feminism—to be ironic if not oblivious). She does this even as she turns two of her female characters into goddess-like all-powerful beings—namely dragons—as if to balance the male power of the earlier novels. Her impulse to adore men—to attentively portray their struggles, foibles, tenderness, and nobility—remains, while her suspicion of female characters also subtly persists. I don’t consider that a failing. It’s refreshing, especially when compared to Tolkien, who absurdly idealizes women (if he bothers to write about them at all). It’s another reason that I find criticism of her “feminism” to be misplaced. Le Guin seems to possess a well-tested knowledge of female treachery— even in a male dominated fantasy world. She is disinclined to treat women as helpless victims. Speaking through Tenar, she scolds the young Kargish princess Seserakh, instructing her to get her act together and become the Queen, the co-ruler of Earthsea, that she is meant to be.