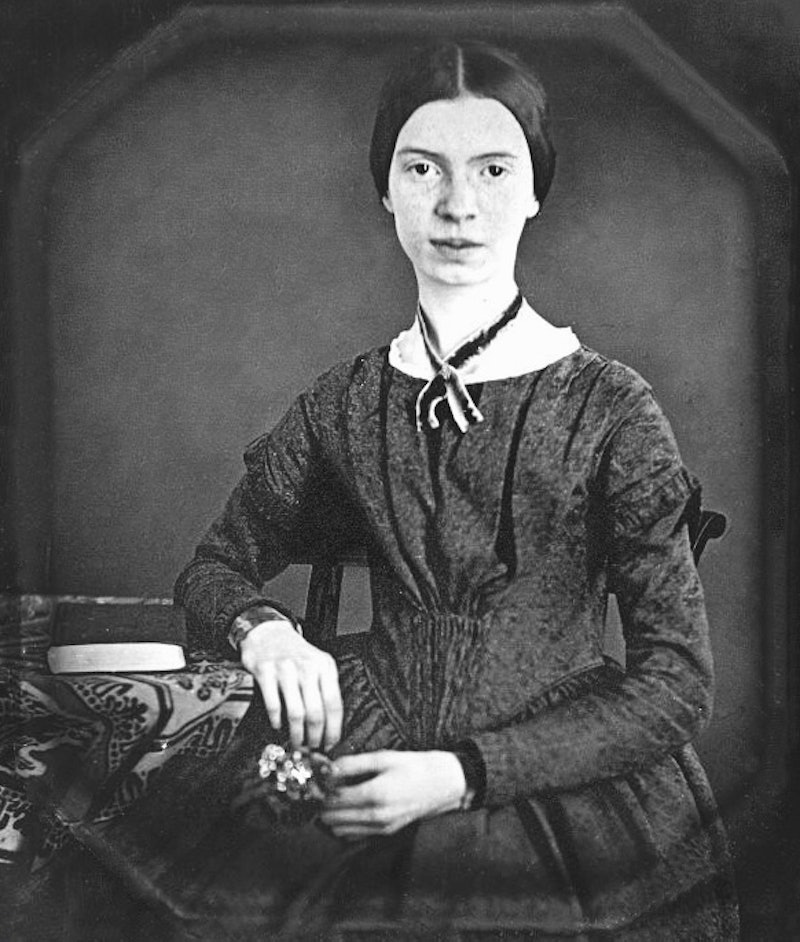

I’m now reading Rebecca Patterson’s book “Emily Dickinson’s Imagery” (published posthumously). Patterson was the first Dickinson scholar (if I’m reading the preface correctly) who, in 1951, posited Dickinson’s lesbian attachments, which was greeted just as you would expect—with shock and rejection by some and revelatory acceptance by others. As Margaret Freeman writes: “[Patterson’s] hypothesis that Emily’s ‘lover’ was female rested on just as much evidence (or lack of it) as other, ‘more acceptable’ theories that have variously identified Charles Wadsworth, George Gould, Edward Hunt, or Samuel Bowles as the (male) object of the poet’s affections…”

But it wasn’t this passage that I wanted to share, but one of the longest endnotes in the book (the best thing in the book so far, and it’s a good book if you like this sort of thing). I found it so engaging that I thought I’d share it in all its glory:

Lydia Maria Child, Letters from New York (1848), p. 106. The name of this pioneer feminist was introduced, apparently by Emily Dickinson herself, at the first of her two meetings with T.W. Higginson. The poet even essayed a little feminist joke, which wholly escaped her visitor. Higginson reported with solemn bafflement that after mentioning her domestic duties she added, “‘& people must have puddings’ this very dreamily, as if they were comets—and so she makes them” (L342a). Such a redoubtable feminist should have remembered Sarah Grimké’s scornful attack on the male dictum that “She that knoweth how to compound a pudding is more desirable than she who skillfully compounds a poem” (The Equality of the Sexes and the Condition of Women, 1838). Grimké must have gotten her pudding and her title from “The Equality of the Sexes” by “Constantia” (Judith Sargent Murray), who demanded (Massachusetts Magazine March-April 1790) whether it was “reasonable that a candidate for immortality, for the joys of heaven, an intelligent being, who is to spend at eternity in contemplating the works of the Deity, should at present be so degraded as to be allowed no other ideas, than those which are suggested by the mechanism of the pudding?” Royal Tyler’s Van Rough approved the general opinion “that if a woman knew how to make a pudding, and to keep herself out of fire and water, she knew enough for a wife,” (The Contrast, act 1, scene 2, a play almost certainly known to Emily Dickinson). Of course it all went back to Samuel Johnson, who saw the necessity of asserting that “My old friend, Mrs. Carter, could make a pudding as well as translate Epictetus.” Best known to Emily was Charlotte Brontë’s famous diatribe against those “more privileged fellow-creatures” who thought women should “confine themselves to making puddings” and the like trivial occupations (Jane Eyre), although she could not have read Elizabeth Barett’s attack on the “pudding-making and sock-darning theory” of women’s activities noticed earlier. There was something about making puddings that set a feminist’s teeth on edge, and Emily expected Higginson to know it.

Can you just imagine Emily reading that sarcastic little dictum that “She that knoweth how to compound a pudding is more desirable than she who skillfully compounds a poem”!

Of course, if we treat “pudding” metonymically (which Dickinson probably was), then it can mean all sorts of trivial things. (Her barb was directed at people, after all, not just men.) People must eat—granted; but a pudding is not that. A pudding is what we gobble down whilst gossiping over that little tramp, Miss Littleslip, who dared to show her ankles during Reverend Snipple’s catechism. “If you must write your little poems, Emily, then why not go to your room? Or you could make yourself useful? Why don’t you bring us a little pudding.”

It’s going to be my new motto.

“& people must have their puddings.“