- February 22, 2009 – After reading this post, you might enjoy a colorcoded scansion of Birches included with a scansion of Frost’s Mending Wall.

- April 25, 2009 – Added audio of Frost reciting Mending Wall.

- May 9, 2009 – Added notes about the poem and discussed Frost’s erotic bent.

Balance

….the poem is more about striking a balance between getting “away from earth” and then coming “back to it” than it is about overcoming fear. He told his former student, John Bartlett: “It isn’t in man’s nature to live an isolated life. Freedom isn’t to be had that way. Going away and looking at a man in perspective ,and then coming back… that is what’s sane and good.” In one interview in 1931, he extolled the virtues of “striving to get the balance.” He added, “I should expect life to be back and forward–now more individual on the farm, now more social in the city,” reflecting the pattern of his own life. (Robert Frost: The People, Places, and Stories Behind His New England Poetryp. 77)

So wrote Lea Newman in her introduction to Birches. The genius of the poem is in its beautiful and powerfully sustained use of a fairly straightforward extended metaphor – swinging birches as a metaphor for balance. Frost is careful not to over interpret that balance. It could be between earth and spirit, nature and civilization, childhood and manhood, love and loss. The reader will bring to the poem his or her own meaning – and it is this capacity of the poem that makes it a great poem, a work of genius.

You Decide

For most readers there’s no hidden subtext beyond what’s grasped intuitively.

But this hasn’t stopped some interpreters. For instance, in Robert Frost: Modern Poetics and the Landscapes of Self, Frank Lentricchia remarks:

Those “straighter, darker trees,” like the trees of “Into My Own” that “scarcely show the breeze,” stand ominously free from human manipulation, menacing in their irresponsiveness to acts of the will.

I’ve read Birches countless times, and the feeling of an ominous menace never once crossed my mind. To read this kind of interpretation into the imagery requires some kind of context and there simply is none – not in two lines. And referring to “Into my Own”, as though the two poems were somehow related or created the context for such an interpretation, is nonsensical. But the bottom line is that there doesn’t have to be a symbolic undercurrent (or double meaning) to every single word or image. Close readers and academics love nothing more than teasing out interpretations, but just because it can be done, doesn’t mean there’s any objective validity to the interpretation. At some point, such exercises strike me as being more like parlor games.

Just because the other trees are darker doesn’t mean that they are ominous. Fact is, every single tree in the New England landscape is darker than the birch. And for the most part (and after a good ice storm) most other trees are, factually, straighter than birches. In The Wood Pile, Frost refers to the view as being “all in lines/Straight up and down of tall slim trees,” One need not read any more into Frost’s imagery than the simple fact of it.

But, naturally, if Lentricchia is going to invoke menace, he needs to explain why (to justify that interpretation). He writes that they are menacing in their “irresponsiveness to acts of human will”. I just don’t buy it.

At best, one would need to make the assumption that Frost’s use of the word dark always constituted some kind of menace when used in reference to trees or the woods. But in his most famous poem, Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening, Frost writes that “The woods are lovely, dark and deep”. Despite Frost’s use of the word lovely, this hasn’t stopped close readers from suggesting that Frost was contemplating suicide and that loveliness, far from being praise of the New England wood in winter, was a contemplation of the lovely, dark and deep oblivion that is suicide (or so they interpret it). Richard Poirer is among those who have made this suggestion. By the absence of a comma between the word dark and the word and he concludes that the “loveliness thereby partakes of the depth and darkness which make the woods so ominous.” The italics are mine. But Poirier’s reading could hardly be called objective. There is, in fact, no way of knowing what significance such punctuation might have held for Frost. However, Frost did have a thing or two to say about ominous interpretations. William Pritchard writes, in Frost: A Literary Life Reconsidered:

Discussion of this poem has usually concerned itself with matters of “content” or meaning (What do the woods represent? Is this a poem in which suicide is contemplated?). Frost, accordingly, as he continued to to read it in public made fun of efforts to draw out or fix its meaning as something large and impressive, something to do with man’s existential loneliness or other ultimate matters. Perhaps because of these efforts, and on at least one occasion – his last appearance in 1962 at the Ford Forum in Boston- he told his audience that the thing which had given him most pleasure in composing the poem was the effortless sound of that couplet about the horse and what it does when stopped by the woods: “He gives the harness bells a shake/ To ask if there is some mistake.” We might guess that he held these lines up for admiration because they are probably the hardest ones in the poem out of which to make anything significant: regular in their iambic rhythm and suggesting nothing more than they assert… [p. 164]

All of which is to say, Frost had little patience for self-pity or, by extension, suicide. One need only read Out, Out to get a sense of Frost’s personality. In short, one can contemplate the soothing darkness and loveliness of the woods without contemplating suicide. But you decide.

….

But swinging doesn’t bend them down to stay.

Ice-storms do that.Often you must have seen them

Loaded with ice a sunny winter morning

After a rain. They click upon themselves

As the breeze rises, and turn many-coloured

As the stir cracks and crazes their enamel.

Soon the sun’s warmth makes them shed crystal shells

Shattering and avalanching on the snow-crust

Such heaps of broken glass to sweep away

You’d think the inner dome of heaven had fallen.

They are dragged to the withered bracken by the load,

And they seem not to break; though once they are bowed

So low for long, they never right themselves:

You may see their trunks arching in the woods

Years afterwards, trailing their leaves on the ground,

Like girls on hands and knees that throw their hair

Before them over their heads to dry in the sun.

But I was going to say when Truth broke in

With all her matter-of-fact about the ice-storm,

I should prefer to have some boy bend them

As he went out and in to fetch the cows–

The italicized lines bracket a digression that Frost characterizes as Truth. What does he mean? In fact, the differentiation Frost implies between Truth and his playful, imaginary fable of the boy climbing the birches, is central to the poem’s meaning. The world of Truth could be construed as the world  of science and matter-of-factness – a world which circumscribes the imagination or, more to the point, the poetic imagination, Poetry. The world of the poet is one of metaphor, symbolism, allegory and myth making. At its simplest, Frost is describing two worlds and telling which he prefers and how he values each. “One could do worse than be a swinger of birches.” And by that, he could almost be saying: One could do worse than be a poet.

of science and matter-of-factness – a world which circumscribes the imagination or, more to the point, the poetic imagination, Poetry. The world of the poet is one of metaphor, symbolism, allegory and myth making. At its simplest, Frost is describing two worlds and telling which he prefers and how he values each. “One could do worse than be a swinger of birches.” And by that, he could almost be saying: One could do worse than be a poet.

The underlined passage “You’d think the inner dome of heaven had fallen”, has been nicely interpreted as a reference to Ptolemaic astronomy (which believed that the planets and stars were surrounded by crystal spheres or domes). I like that interpretation and I can believe that Frost intended it. The inner dome and its shattered crystal shells like “heaps of broken glass” fit neatly within the allusion. But there is significance in the allusion. The Ptolemaic model of the universe was a poetic construct – a theory of the imagination rather than matter-of-factness. In this sense, Truth as Frost calls it (or modern science) has collapsed the inner dome of the poetic imagination and replaced it with something that doesn’t permit the poet’s entry. The shattered inner dome of the imagination (of the myth makers) has been replaced by fact – by science.

And in this light, the entirety of Frost’s description, climbing the birches, just so, and swinging back down, becomes a kind of description for the life which the poet seeks and values – the imaginative life of the poet:

…. He learned all there was

To learn about not launching out too soon

And so not carrying the tree away

Clear to the ground. He always kept his poise

To the top branches, climbing carefully

With the same pains you use to fill a cup

Up to the brim, and even above the brim.

Then he flung outward, feet first, with a swish,

Kicking his way down through the air to the ground.

So was I once myself a swinger of birches.

And so I dream of going back to be.

It’s when I’m weary of considerations,

And life is too much like a pathless wood

Where your face burns and tickles with the cobwebs

Broken across it, and one eye is weeping

From a twig’s having lashed across it open.

I’d like to get away from earth awhile

And then come back to it and begin over.

May no fate willfully misunderstand me

And half grant what I wish and snatch me away

Not to return. Earth’s the right place for love:

I don’t know where it’s likely to go better.

I’d like to go by climbing a birch tree….

The poet learns all there is to learn about “not launching out too soon”. He could be describing the art of poetry. You cannot swing from a birch without the right height. But if you also climb too high, if your ambitions exceed the matter of your poem, the birch will break . You must write your poetry, climbing carefully, with the “same care you use to fill a cup,/Up to the brim, and even above the brim.” But I don’t want to limit the poem’s meaning to just this. Frost is describing more than the poet, but a whole way of interpreting the world.

It’s the difference between the mind that seeks objective truths, irrespective of the observer, and the mind that perceives world as having symbolic, metaphorical and mythical significance. It’s the world of religion and spirituality. Its the world of signs and visions – events have meaning. In the scientific world view, nothing is of any significance to the observer: life is like a “pathless wood”, meaningless, that randomly afflicts us with face burns, lashing us, leaving us weeping. The observer is irrelevant. In some ways, science is anathema to the poet’s way of understanding the world. It’s loveless. And that’s not the world Frost values. “Earth’s the right place for love,” he writes. The woods that he values have a path and the birches are bent with purpose.

But having said all that, Frost also acknowledges a balance.

I’d like to go by climbing a birch tree

And climb black branches up a snow-white trunk

Toward heaven, till the tree could bear no more,

But dipped its top and set me down again.

That would be good both going and coming back.

If we read him right, he seems to be saying that he prefers not to be too much in one world or the other. Let him climb toward heaven, both literally and figuratively, but let him also be returned to earth. Having written this much, Frank Lentricchia’s own interpretation of the poem’s divisions may be more easily understood:

….There is never any intention of competing with science, and therefore, there is no problem at all (as we generally sense with many modern poets and critics) of claiming a special cognitive value for poetry. In his playful and redemptive mode, Frost’s motive for poetry is not cognitive but psychological in the sense that he is willfully seeking to bathe his consciousness and, if the reader consents, his reader’s as well, in a free-floating, epistemologically unsanctioned vision of the world which, even as it is undermined by the very language in which it is anchored, brings a satisfaction of relief when contemplated…..

If I may be so bold as to interpret (and interpreting academese does take some boldness), what Lentricchia seems to be saying is that Frost’s philosophical stance does not arise from any direct experience (as stated in the poem). Direct experience would be “epistemologically sanctioned”. Epistemology, a word coddled and deployed by academics with fetishistic ardor, is the “branch of philosophy that investigates the origin, nature, methods, and limits of human knowledge.” So, to interpret, Lentricchia appears to be saying that Frost’s “vision/philosophy” is not “epistemologically/experientially” “sanctioned/based“. In short, Frost’s experience (and that of the readers) is that of the poet and poetry – the purely subjective realm of imagination, story telling and myth making.

Interestingly, those who criticize the poem for being without basis in experience (Lentricchia is not one of them) seem blissfully unaware that this is precisely the kind of knowing that the poem itself is criticizing and examining. That is, the poem is its own example of myth-making — the transformative power of poetry. Yes, says Frost, there is the matter-of-fact (epistemologically sanctioned) world, but there is also the poetical world – the world of metaphor and myth that is like the slender birch (and the poem itself). It can be climbed but not too high. The matter-of-fact world is good to escape, but it is also good to come back to.

John C Kemp, in Robert Frost and New England: The Poet as Regionalist, goes further in explaining what some readers consider the poem’s weaknesses.

“Mending Wall,” “After Apple-Picking,” and “The Wood-Pile” are centered on specific events that involve the speaker in dramatic conflicts and lead him to extraordinary perspectives. ¶ (….)however, “Birches” does not present a central dramatized event as a stimulus for the speaker’s utterance. Although the conclusion seems sincere, and although Frost created a persuasive metaphorical context for it, the final sentiments do not grow dramatically out of the experiences alluded to. (….) Frost’s confession that the poem was “two fragments soldered together” is revealing; the overt, affected capriciousness of the transitions between major sections of the poem (ll. 4-5, 21-22, and 41-42) indicates that instead of striving to establish the dynamics of dramatized experience, he felt he could rely on the force of his speaker’s personality and rural background. In early editions, a parenthetical question, “(Now am I free to be poetical?),” followed line 22, making the transition between the ice storm and the country youth even more arbitrary.

My own view is that rather than making the poem feel arbitrary, the question Now am I free to be poetical? makes Frost’s thematic concerns too explicit. The question too sharply defines the contrast between the matter-of-fact and the poetical. In short, Frost may have felt that the question overplayed his hand. (Some critics read this question as an affectation. I don’t. I read it as signaling the poem’s intent, a “stage direction” that Frost later removed.)

Frost was striving for balance both in poem and subject matter — between the poetical and the matter-of-fact.

Another Interpretation

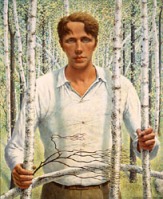

Some readers have interpreted the poem as being about masturbation. George Monteiro, Robert Frost and the New England Renaissance, alludes to this interpretation in the closing paragraphs of his own analysis. (And if you have searched on-line, then you have probably found the same interpretation in some haphazard discussions.) But here is what Monteiro (in full) has to say:

If physiologically there is some sort of pubescent sexuality taking place in the “swinging” of “birches,” it is not surprising, then, that the boy has “subdued his father’s trees” by “riding them down over and over again” until “not one was left for him to conquer” and that the orgasmic activity should be likened to “riding,” which despite the “conquering” can be done time and again. One need only note that the notion of “riding,” already figurative in “Birches,” reappears metaphorically in Frost’s conception of “Education by Poetry,” wherein he writes: “Unless you are at home in the metaphor, unless you have had your proper poetical education in the metaphor, you are not safe anywhere. Because you are not at ease with figurative values: you don’t know . . . how far you may expect to ride it and when it may break down with you.” And what is true for metaphor and poetry is true for love. Frost insisted that a poem “run . . . from delight to wisdom. The figure is the same as for love. Like a piece of ice on a hot stove the poem must ride on its own melting.” Then it is totally appropriate within the metaphor of “swinging birches” that even the storm-bent trees should look to the adult male like “girls on hands and knees that throw their hair / Before them over their heads to dry in the sun.” No wonder, then, and fully appropriate it is, that when the poet thinks that his wish to get away from earth might by some fate be misunderstood such that he be snatched away never to return, his thought is that “Earth’s the right place for love.” At some level of his consciousness the pleasurable activity of “swinging birches” has transformed itself into the more encompassing term “love.” One might say, within the logic of this reading of the poem, that “Earth’s the right place for [sexual] love,” including onanistic love. The same sexual metaphor runs through the final lines of the poem as the mature poet thinks of how he would like to go but only to come back.

It’s an intriguing interpretation, but I don’t buy it. Frost was capable of writing about sexual themes, but there’s no precedent, elsewhere in his poetry, for such a sleight of hand. Just as any number of critics can convince themselves that Shakespeare was a lawyer, a homosexual, Edward de Vere, Francis Bacon, a woman, and even Queen Elizabeth, one can surely find evidence for just about any interpretive inference in just about any poem. Figurative language and metaphor, by definition, lend themselves to multiple interpretations.

The interpretation must remain, at best, purely speculative and very doubtful at that.

Then again, many modern critics and readers feel that the author’s intentions are irrelevant. Fortunately for the reader, the same rules apply to those critics and readers. Just because an interpretation can be made doesn’t mean they’re right or relevant. Again, you decide.

Robert Frost & the Blank Verse of Birches

I wanted to take a look at Robert Frost’s blank verse (Iambic Pentameter) and Birches is a beautiful example. I understand that this won’t interest most readers and many may find it irrelevant. The rest of this post for those who enjoy studying how meter can be used to masterful effect. If you’re one of those, be sure to comment. I would enjoy hearing from you. In an effort to avoid a book-length post I’ll read the poem 10 lines at a time. But first, here is the poem in its entirety along with my scansion. If you are new to scansion then take a look at my post on the basics.

Frost recites Birches:

For the colorcoded version click here.

Birches

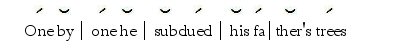

Lines 1-10

As with The Road Not Taken, the other Frost poem I looked at, I listened to Frost read the poem before I scanned it. I actually would have been tempted to scan it differently before listening. The first line for example, I might have scanned:

When I |see bir|ches bend |to left |and right

That is, I might have been tempted to put the emphasis on When instead of I. Critics sometimes accuse metrists of unnaturally fitting a poem’s language to a metrical pattern. Read anapests, they say, don’t elide the anapest to read as an Iamb. What they forget though, is that poets who right metrical poems are themselves metrists. That’s why, when I read a line like To be or not to be that (is) the question, I prefer to put the emphasis on is. (It’s in keeping with the Iambic Meter). Similarly, listening to Frost, one can clearly hear him reading the meter. When I, he writes and reads.

Interestingly, Frost reads the fifth line as follows:

Interestingly, Frost reads the fifth line as follows:

But swinging them doesn’t bend them down to stay

As ice-storms do.

Instead of “Ice storms do that“. I like the printed version better because it varies the Iambic beat and makes the thought feel more like a colloquial aside. My guess is that Frost was reciting this from memory and that the Iambic alteration was easier to remember (which was partly blank verse’s advantage on the Elizabethan stage). The fifth line ends with an iambic feminine ending. And I just now noticed that I forget to mark morning, at the end of line 6 – corrected in the extract.

Up to this point, Frost has written an Iambic Pentameter that Shakespeare would have been recognized and accepted in Shakespeare’s day. The first four lines are strictly Iambic Pentameter. This has the effect of firmly establishing the meter of the poem. As long as Frost doesn’t vary too much, for this point on, the ear will register whatever he does as variations on an established Iambic Pentameter meter. I won’t say that Frost did this deliberately. In other poems, like The Road not Taken, he varies the metrical line from the outset. In this case, though, the effect is such that the lines stabilize the metrical pattern early on.

Ice-Storms and often (in line 6) are trochaic feet.

With line 7 one finds a nice metrical effect with As the |breeze ri|ses. The spondaic foot has the effect of reproducing the rising breeze – breeze being more emphasized than the, and ris-es being more emphasized than breeze. Unlike some, I won’t go so far as to say that Frost toiled for hours producing this effect, but he was probably aware that the natural progression of the language nicely fit the metrical pattern.

In his book on blank verse called Blank Verse (which I’ve been meaning to review) Robert B. Shaw provides his own scansion of this passage (or a part of it.)

Here it is:

It’s gratifying to see that we mostly agree. Where our scansion doesn’t match is probably because I’ve followed Frost’s own reading. For instance, Frost gives greater emphasis to the word shed than Shaw does and gives less emphasis to crust (in snow-crust) than Shaw. I wouldn’t call Shaw’s reading incorrect, simply different than Frost (because Shaw’s reading recognizes the overall iambic pattern – unlike the scansion of The Road Not Taken at Frostfriends.org – which I criticized elsewhere.

It’s gratifying to see that we mostly agree. Where our scansion doesn’t match is probably because I’ve followed Frost’s own reading. For instance, Frost gives greater emphasis to the word shed than Shaw does and gives less emphasis to crust (in snow-crust) than Shaw. I wouldn’t call Shaw’s reading incorrect, simply different than Frost (because Shaw’s reading recognizes the overall iambic pattern – unlike the scansion of The Road Not Taken at Frostfriends.org – which I criticized elsewhere.

More to the point, the story which meter tells reinforces the content of the poem. The poem, which up to this point has been fairly standard iambic pentameter, disrupts the metrical flow just as the rising breezes disrupt the tree’s “crystal shells”. The dactylic first foot Shat-ter-ing – one stressed syllable followed by two unstressed syllables, upsets the ear’s expectation, disrupting the iambic flow. The final foot of this line – |the snow-crust – is called a heavy feminine ending. Whereas the usual iambic feminine ending ends with an unstressed syllable, a heavy feminine ending ends with an intermediate or strongly stressed syllable. This variant foot was wildly popular in Jacobean theater. Frost probably could have avoided it; but the use of it serves to further disrupt the metrical pattern – further mirroring the disruption of the “crystal shells”. All of this is an effect that is hard, and in some ways impossible, to reproduce in Free Verse.

The next line is one of the more metrically interesting:

![]()

I can’t tell, but Shaw either has forgotten to mark the second syllable of heaven, or he has chosen to elide heaven such that it reads heav‘n – making it a one syllable word. Frost pronounces it fully as two syllables. So… what makes this final foot interesting is in what to call it. Strictly speaking, it’s a tertius paeon – two unstressed followed by a stressed and unstressed syllable. Another way to read the line would be as a long line or hexameter line.

![]()

Hexameter lines can be an acceptable variant with an Iambic Pentameter pattern, but with a pyrrhic (weak) fifth foot and a trochaic (inverted) final foot, the feet seem too weak to support a hexameter reading (the extra foot). My preference is to read a line as being pentameter (having five feet) unless a line’s “feet” are strong enough to support hexameter.

Frost’s metrical habit is to see anapestic feet as a perfectly acceptable variant to iambic feet – frequently calling them loose iambs. With that in mind, my own reading is that Frost has substituted an anapestic feminine ending for an iambic feminine ending. To my ear, it’s an elegant variation – and not one found prior to Frost (to my knowledge). Frost will use this foot again later in the poem.

Of interest in the next two lines are the elision of They are to They’re. Some metrists, like George T. Wright, are criticized for too readily reducing anapests to iambs by the use of elision – as if he were philosophically opposed to anapests. If the poets had meant the lines to be read as iambs, the reasoning goes, they would have written them as iambs. If you’ve read my previous posts on meter you’ll know that, if I can, I tend to elide anapests to read as iambs. I learned this technique by reading Wright’s books on meter.

Of interest in the next two lines are the elision of They are to They’re. Some metrists, like George T. Wright, are criticized for too readily reducing anapests to iambs by the use of elision – as if he were philosophically opposed to anapests. If the poets had meant the lines to be read as iambs, the reasoning goes, they would have written them as iambs. If you’ve read my previous posts on meter you’ll know that, if I can, I tend to elide anapests to read as iambs. I learned this technique by reading Wright’s books on meter.

I feel a little vindicated noticing that when Frost reads or recites Birches, he pronounces (elides) They are as They’re – despite the fact that he hasn’t marked them as such. (Mind you, his lines would be perfectly acceptable variants if read them as anapests.) So, I don’t make this stuff up.

A last observation on these ten lines. It is interesting to note that balance Frost establishes between standard Iambic Pentameter and variant lines. The seventh and eighth line from the extract above are varied with trochaic and anapestic feet, but notice how both these lines are balanced by perfect Iambic Pentameter lines.

More so than the meter, the next ten lines are interesting for their Frostian colloquialism. Before Frost, no 19th Century Poet (or earlier unless they were writing Drama) would have stopped the poem mid-breath to say something like: But I was going to say. Up to this point, the poem’s tone could be considered fairly traditional, but Frost, as interrupts the elevated tone with colloquial banter: broke in, all her matter-of-fact, I should prefer, fetch the cows.

- Note: There’s no denying the eroticism, by today’s standards, in the lines: “Like girls on hands and knees that throw their hair hair/ Before them over their heads…” I have a truffle pig’s nose for eroticism in poetry. Trust me. Read my analysis of Sidney and Dryden if you don’t believe me. However, I think it’s reading too much into this imagery if one takes it as the starting point for an erotic subtext in the entirety of the poem. Several reasons:

1.) In 1913, when this poem was published, what was tolerated in terms of sexuality and eroticism was worlds apart from now (or the Elizabethan Age for that matter). There was erotic literature, but it was very underground. Women couldn’t vote. They couldn’t swim at the beach unless they were, practically speaking, fully clothed. Miller’s Tropic of Cancer, published just over twenty years later, wouldn’t be permitted on American shores for another 50 years! Doggy style was not the first thing to pop into readers’ minds when they read this (or else the poem would have been banned). Pornographic language and imagery was practically non-existent in the public sphere.

2.) Frost himself was risk averse. He didn’t achieve any real recognition until he was in his mid-forties and he would not have risked his reputation if he had thought the image was too suggestive. He was nothing if not conscious if his own image as a sort of New England farmer/poet. And there’s is simply no other precedent for this kind of suggestiveness in any of his other published poetry. There is some poetry that remained unpublished however – humorous and one step removed from bathroom graffiti. Here’s an example:

Sam-ball-ism

The symbol of the number ten–

The naught for girls, the one for men–

Defines how many times does one

In mathematics or in fun

Go as you might say into zero.

You ask the heroine and hero.

This was about as close as Frost got to anything “erotic”. He joked about sex, one notch above crude, or treated sexuality as a dark undertow in the lives of men and women, The Subverted Flower for example.

3.) It’s too obvious. Even in his unpublished pranks, he was indirect. No where else is Frost ever so explicit about sexuality (if one insists on interpreting the line as such). Though some interpreters will probably still make the argument, I personally don’t buy it.

In terms of meter, only the very rare 19th century (or earlier) poet would have ended a line with a trochaic foot. Frost does so with baseball in the 5th line and will do so again later in the poem. His willingness to extend variant feet into places where they hadn’t normally been helps lend his poetry a colloquial feel. Frost isn’t willing to  sacrifice the “sound of sense” for the sake of meter. But he also strikes a balance. Once again, notice that he brackets this line with perfectly Iambic Pentameter lines before and after. In the 9th line, he substitues an anapestic final foot for an iambic foot – a much freer variation than used by any poet in the generation preceeding him.

sacrifice the “sound of sense” for the sake of meter. But he also strikes a balance. Once again, notice that he brackets this line with perfectly Iambic Pentameter lines before and after. In the 9th line, he substitues an anapestic final foot for an iambic foot – a much freer variation than used by any poet in the generation preceeding him.

I scanned Line 8 as a headless line (the initial unstressed syllable is omitted) and the third foot as anapestic – in keeping with his willingness to substitute iambs with anapests. However, one can also read the line as starting with two trochaic feet:

I’m not philosophically opposed to this reading. Two trochaic feet at the start of a line is perfectly acceptable. The reason I prefer my own reading, I suppose, is because I hear the phrasing, not as trochaic, but Iambic – One| by one | he sub-dued. This is where the art of scansion comes into play; and I’m not going to argue that my preferred reading is the right one (in this case).

Notice how Frost echoes one by one with over and over – it’s a nice touch and works within the metrical patterning he allows himself.

The next ten lines come with one metrically ambiguous line – the 6th line.

I scanned the line as follows:

![]()

This makes the line pentameter and my hunch is that this is the spirit in which Frost wrote it.I notice that in his reciting of the poem, he is careful to give carefully it’s full three syllables. However, were it not part of a well established Iambic Pentameter poem, I would be tempted to scan the line as follows:

Essentially trochaic tetrameter. Either way, the meter echoes the hesitant and careful climbing of the boy. This line, of all the lines, most threatens the Iambic Pattern and, in that respect, most draws attention to what the boy is doing – climb-ing care-fully.

- Alternate Readings November 11th 2016: I’ve just been having an email exchange with the poet Annie Finch, one of the finest “formalist” poets currently writing. She has a Ph.D. and currently teaches poetry. She strongly takes issue with my reading of the line above (and the next one below) as headless (∧). For example, where I read:

(∧} And |not one |but hung limp,| not one |was left

She reads:

And not | one but | hung limp,| not one |was left

I’ve used gray-scale and italics to indicate the level of stress she assigns to each word. So, “not one” receives more stress than “And”, but not as much as the bolded words.

As I mentioned above, I chose to scan the poem the way Frost read it. This is not the only way to scan the poem; but since we have his recitation I thought it might be interesting to scan it the way he imagined it . Even in that respect my scansion is open to differences of opinion: Did Frost really emphasize a word as much as I’ve marked? That’s all subjective. Annie Finch’s reading, on the other hand, disregards the way Frost reads his poem. That said, I think her reading is equally valid and undoubtedly reflects the way she reads the poem. She writes:

“You mention that you based the scansion of the poem on Frost’s own recorded performance of it. I honor your interest in respecting Frost’s voice here, but this is really not a viable way to scan (his pronunciation of poems is so subjective that if scansion were dependent on the way a poem is spoken, meter would have ceased to exist long ago). “

I agree that Frost’s reading is subjective, but I’d assert that all readings are subjective and that meter has nevertheless survived, so why not inquire into Frost’s own metrical preferences? As regards that, though, Annie Finch stated her guiding principle at the outset of our exchange:

“As you will see throughout A Poet’s Craft, the SIMPLEST SCANSION IS ALWAYS BEST…” [Uppercase is her own.]

The book she refers to is her own. Her assertion that the simplest scansion is always the best leads her to write that my own scansion “is absurdly and needlessly complex.” I disagree and I don’t agree with her assertion if treated as an invariable rule (though it’s certainly useful as a guiding principle). In the case of Frost’s poem we can, at minimum, say that her “rule” leads her to read the lines counter to the way Frost reads them. Does that make her scansion wrong? No. I would, however, say that this demonstrates how scansion is less science than art. Do you care about how a poet reads his or her work? Does it matter when scanning? Does it matter if your scansion agrees with the poet’s? These questions are themselves debatable, but that they’re debatable is worth emphasizing. I don’t and would not claim that my scansion is the “correct” scansion—just my own spin on the matter. She adds:

The next two lines follow a more normative pattern with trochaic and anapestic variant feet.

The most elegantly metrical lines follow with the 9th & 10th line of the extract:

Then he flungoutward, feet first, with a swish

Kicking his way down through the air to the ground

The spondee of flung out beautifully reinforces the image by disrupting the metrical pattern, as does feet first. Kick-ing is further reinforced and emphasized by being a trochaic first foot. The word down, as Frost recites it, trochaically disrupts the meter again, more so than if it had been iambic.

At Frostfriends.org you will find the following:

Birches: “It’s when I’m weary of considerations.” This line is perfect iambic pentameter, with an extra metrical (feminine) ending.

Their statement is incorrect. This line is not perfect iambic pentameter. A perfectly iambic pentameter line would not have a feminine ending (an amphibrach) in the final foot. It would have an iambic foot (if it were “perfect” iambic pentameter). The correct thing to say would have been: This is a perfectly acceptable variant with an iambic pentameter pattern.

Notice the trochaic final foot in the 9th line – a thoroughly modern variant.

As with the other lines, I scanned the 10th line as headless to preserve an Iambic scansion and because I thought it most accurately reflected Frost’s own reading of the poem. (That is, the feeling is Iambic rather than trochaic. ) While scansion doesn’t, by in large, reflect phrasing, there is a certain balance to be struck; and I have tried to do so in these lines.

The fourth line is the most metrically divergent. I have scanned the line as Iambic Tetrameter with an anapestic feminine ending. The alternative would be to read it as follows:

If this is what Frost imagined, then my own feeling is that the scansion fails as such. The pyrrhic fourth foot is exceptionally weak, even for pyrrhic feet, while a trochaic final foot seems inadequate to restore the underlying Iambic Pentameter pattern after such a weak fourth foot. Given precedence for an anapestic feminine foot earlier in the poem, and in the final line, the line makes much more sense if read as Tetrameter with an anapestic feminine foot. I don’t see this as being outside the bounds of an acceptable variant. Interestingly, the line remains decasyllabic so that the ear doesn’t so much perceive a short line as a a variant line.

This line has been preceded by some richly varied lines. As is Frost’s habit, he grounds the meter with the iambically regular 6th and 7th line. To that end (in his recitation) Frost effectively reads Toward as a monosyllabic word, emphasizing the return to Iambic Pentameter.

The closing two lines are conservative in their variants. Frost has reaffirmed the Iambic Pentameter and he’s not going to disrupt it again. The message, at this point, is what matters. The meter reinforces the calm and measured summation. In the second to last line, the only variant is an anapestic fourth foot.

With the last line, the temptation is to read the first foot as One could| do worse, but Frost, in reciting the poem, once again reaffirms the iambic meter by emphasizing could. This sort of metrical emphasis, emphasizing words that might not normally be emphasized while de-emphasizing others that are more normally emphasized, is a Frostian specialty made possible by his use of meter. Free Verse can’t reproduce it. The last line, as Frost reads it, is regularly iambic until the last foot, at which point he elegantly closes with an anapestic feminine ending.

With the last line, the temptation is to read the first foot as One could| do worse, but Frost, in reciting the poem, once again reaffirms the iambic meter by emphasizing could. This sort of metrical emphasis, emphasizing words that might not normally be emphasized while de-emphasizing others that are more normally emphasized, is a Frostian specialty made possible by his use of meter. Free Verse can’t reproduce it. The last line, as Frost reads it, is regularly iambic until the last foot, at which point he elegantly closes with an anapestic feminine ending.

The final foot, with its anapestic swing and feminine falling off, could almost be said to imitate the swinging of the birch.

Such is the genius of Robert Frost.

Patrick,

I just made the happy discovery of your blog and read this post with great interest. I grew up in Essex Vermont. Graduated from Essex Jct. High School in 1984. Anyway, I can’t help but think that we may be kindred spirits. I too am a poet. I began writing about 16 years ago, quit doing it for many years, then picked it up again about a year-and-a-half ago. I am a house painter (and have also done a lot of old home restoration where I used to live in St. Louis. I am now living in South Carolina with my wife and three children). I know what you mean about sitting at your desk to write unencumbered (of course there’s always tax time!) I just got a new laptop and am enjoying writing more than ever. I also know what you mean about having all of your writing collected in one place. You have done a good bit of writing, I see. I am eager to read some of your stuff and want to check out your self published book.

I enjoyed your scansion? of Frost’s poem, though I am only just beginning to learn about iambs and meter and the like. I really want to learn. I looked at an MFA low-residency program at Seattle Pacific University. It is intense. They say it requires about 25 hours a week. plus it costs over 30 grand for two-and-a-half years! Wow, won’t be doing that anytime soon! My wife says I can start it if we win the Publishers Clearing House.

So, I like your spirit, I like Frost, I like the rhythm of poetry (people tell me that is the distinguishing feature of my poems) and I really like knowing there is a blog where I can learn about poetry–truly a godsend.

My blog is called eellspoems and I have posted almost all of my stuff there (about 40 poems). I will include one here that I completed recently that a fellow in my writer’s group told me reminded him of Frost. It is called The Silver Paths Beneath Me Rise:

The silver paths beneath me rise; they brighten and sustain;

and I, by mortal strides, rejoin their whited old refrain.

The snow, like fairest company, tonight comes soft to call

till every stone and every tree is whitened by its fall.

Luminous, the moon reflects the way upon the row

and I, by soft reflection, leave my footprints as I go.

By steps, each foot conceals a bit of white upon the track,

then shows the outline of a boot upon a silver back.

The silver paths beneath me rise; the night is nearly day;

and I, by mortal strides, go soft beneath their mighty sway.

By the way, I love your license plate. Seeing it on the WordPress poetry page is what made me click on your article in the first place. Also, you have done a wonderful job setting up your website. So much of what I see looks like crap. Yours is easy to get around in and gives the kind of information I actually want to see. Thanks for your hard work and good writing. I know I am going to learn a lot just by further exploration of your website and blog.

Peace, John Eells

LikeLike

Patrick,

I forgot to mention that my wife grew up in Toledo. Have you been to the toledo art museum?

LikeLike

John,

I just came down before going to sleep – saw your comment. It’s really cool to hear from you and it *does* sound like we have a lot in common.

(I just glanced at your blog but want to take a closer look this week-end.)

As to Seattle Pacific’s program, I can’t fathom how any MFA program can teach someone to write poetry. Only writing can do that – and why shell out 30 grand to… well… write? What exactly are they going to teach for 25 hours a week?

I suppose some people need that structure.

I would *love* to be on the teaching end – he wrote hypocritically.

Your poem shows you have an ear for the music in language – which is why it reminds of Frost. You have a strong sense of rhythm, image and pace. You possess all the talent needed to get somewhere (hopefully further than I’ve gotten). Right now it’s a mix of maturity and inexperience. I suspect it won’t take long to find your voice.

I’m wanting to write some posts on the writing of poetry – though I suspect you know most of it.

We have to keep in touch.

The license plate is my pride and joy, by the way. I’ll die in Vermont before I give it up.

LikeLike

Just woke up. I grew up in Ohio but Toledo was the one corner I never visited – that & Ohio’s Northwest.

LikeLike

I just read your review, and it is amazing. I really needed some ideas for a school project, and your commentary definitely put me on the right track. Thanks, I can’t believe I was able to find commentary of this caliber on the internet.

LikeLike

I just wish I had gotten around to revising the interpretive section (as I had planned to).

As it is, it’s all about the meter but not much interpretation. Your comment inspires me to have another go at it. (Which I’m doing right now!)

LikeLike

Pingback: Birches by Robert Frost (Southbank Community Learning Salon) | The London Literary Salon

Pingback: Poetry Salon Monday at The Fields Beneath: April 29th Birches | The London Literary Salon

In line 50 “And then come back to it and begin over”, why do you think Frost chose to use a trochaic final foot instead of writing “begin again”, which seems to me to be both more metrically regular and a more colloquial phrasing? Reading it this way I still like Frost’s version better, so I guess I’m really asking why “begin over” sounds better than “begin again”.

LikeLike

Pingback: Why do poets use iambic pentameter? | How my heart speaks