I felt a Funeral, in my Brain,

And Mourners to and fro

Kept treading - treading - till it seemed

That Sense was breaking through -

And when they all were seated,

A Service, like a Drum -

Kept beating - beating - till I thought

My mind was going numb -

And then I heard them lift a Box

And creak across my Soul

With those same Boots of Lead, again,

Then Space - began to toll,

As all the Heavens were a Bell,

And Being, but an Ear,

And I, and Silence, some strange Race

Wrecked, solitary, here -

And then a Plank in Reason, broke,

And I dropped down, and down -

And hit a World, at every plunge,

And Finished knowing - then -

[F340/J280]

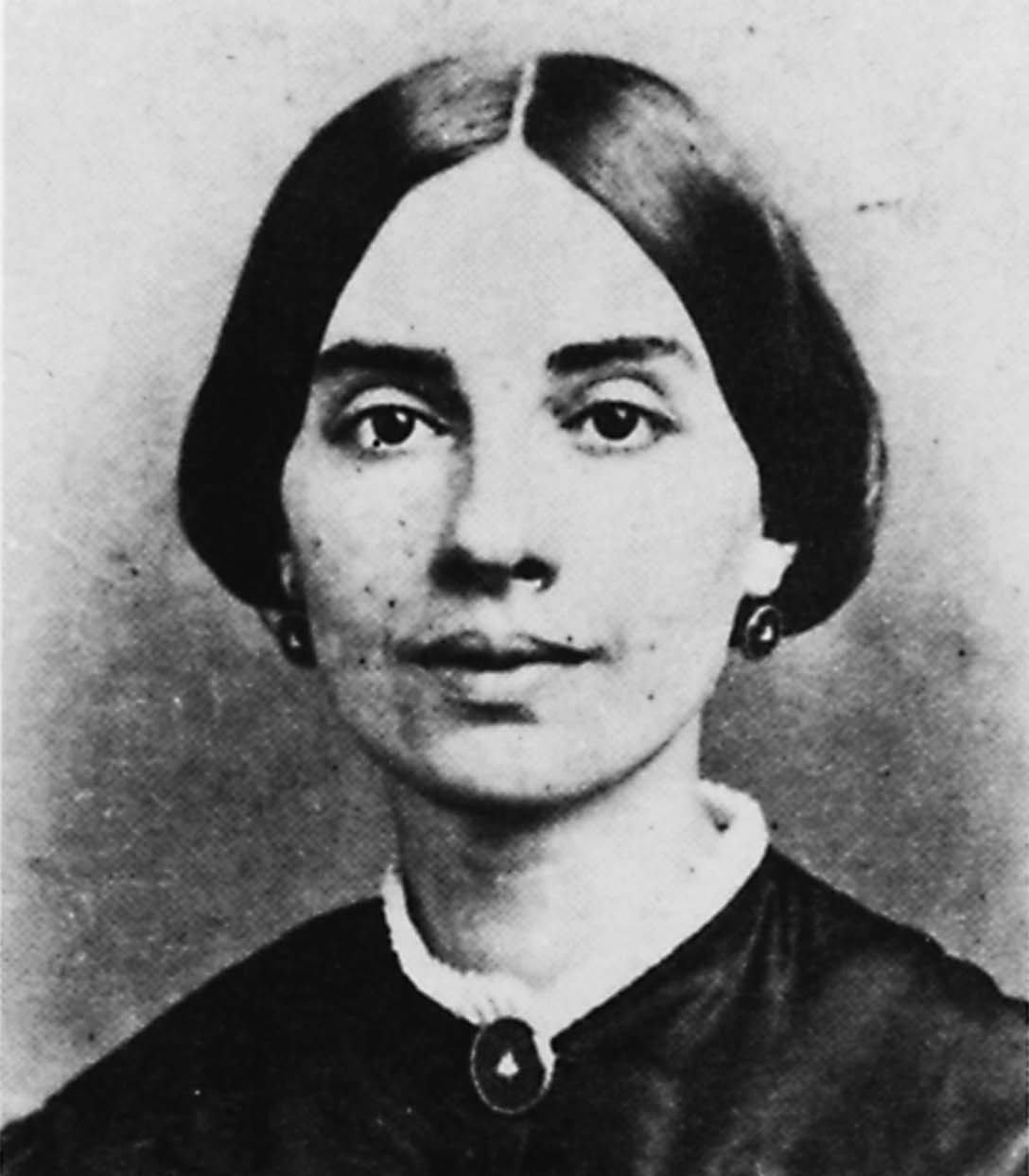

This is a fascinating poem simply because so much of its weight and meaning rests entirely on how one interprets the meaning of a handful of words. Each word exists in a sort of splendid isolation that conversely affects the meaning of every other word. To begin with, how does one interpret “sense”? How does one interpret “Plank”, “World”, “Finished” or “knowing” ? How does one interpret “breaking through”. This latter phrase, fascinatingly, appears twice in an alternative draft. Rather than writing “And Finished knowing”, Dickinson wrote “And Got through — knowing”. So, in one draft at least, the conceit of breaking through and getting through appears both in the first and last stanza, arguing that this conceit of break through is something we should be paying attention to. That is, the central conceit of the poem may not be oblivion or defeat, which is understandably how the poem is universally (as far as I know) interpreted (including recently by Vendler), but the opposite. In my usual contrarian way, I read this poem as a grim triumph; and my reasons for doing so are not just internal to the poem but have to do with the poem that follows it in Dickinson’s fascicle.

I felt a Funeral, in my Brain,

And Mourners to and fro

Kept treading - treading - till it seemed

That Sense [sanity] was breaking through - [in the sense of falling into a chasm]

It’s tempting to read “breaking through” in the sense that sanity was “breaking through” the imagined drama of the funeral, but based on the stanza that follows, my hunch is that this would be misreading Dickinson’s meaning and anachronistic. I looked up breakthrough in the Oxford English Dictionary and was surprised that the noun—a breakthrough—doesn’t appear. I had to go to Webster’s where they pinned the noun’s appearance at 1918 and only in the sense of a military “breakthrough”—as in there was a breakthrough of the enemy’s defenses. It wasn’t until 1968 that the modern usage of “a scientific breakthrough” appeared.

What is the “Funeral”? No one seems to be certain. Some speculate that it was dissappointment as regards a love or friendship, while others suggest a spiritual crisis (her rejection of Christian belief and dogma). (Dickinson’s biopgrahper Sewall writes, for instance, that “Reason “breaks” may be a tortured requiem on her hopes for [Samuel] Bowles both to love her and to accept her poetry… [p. 502]) Later in the poem she will describe the footfall of the funeral attendants as creaking across her soul. In that sense, her soul is the floor, the foundation upon which her existence is predicated, and it’s this floor—her soul—that her sanity is breaking through. In other words, not even her soul can support the weight of her suffering. That floor, her soul, gives out and she plunges into nothingness.

And when they all were seated,

A Service, like a Drum -

Kept beating - beating - till I thought

My mind was going numb -

This stanza is fairly straightforward, but for modern readers, I think, it does the work of clarifying the meaning of the first stanza. Clearly, Dickinson is describing a sort of mental breakdown, first of sanity, then of awareness. I interpret her ‘mind going numb’ as her failing awareness of anything other than suffering.

And then I heard them lift a Box

And creak across my Soul

With those same Boots of Lead, again,

The reader is likely meant to interpret the ‘Box’ as a casket (within which lies her “deceased” relationship, beliefs or she herself), but in her numb (touchless) and senseless (visionless) state, the only sense left to her is hearing. Lead would be a highly unlikely metal for heels, being soft and malleable, but I was curious if metal heels, of any kind, were a thing in the 19th century. A not-exhaustive search didn’t turn up anything. Dickinson was likely describing the heavy footfall of the mourners as leaden. Additionally, those carrying a casket are likely to walk in lock-step and their steps will be made heavier by the weight of the corpse within. If the corpse is Dickinson herself—or her mind—then the floor (her soul) is the last creaking stay against her ultimate descent into nothingness—although that begs the question: What exactly is her soul—what does Dickinson consider it?—if it’s the floor on which her being exists, then what falls through? How does she distinguish her soul from her mind? If it’s not her soul tumbling into nothingness, then what is it? But it’s also possible to read too closely and too literally. Her imagery is not static but makes her soul both the floor and the essence that falls through its own being.

Then Space [existence] - began to toll,

As all the Heavens were a Bell,

And Being, but an Ear,

[All of existence was the bell and I was nothing but the Ear.]

And I, and Silence, some strange Race

Wrecked, solitary, here -

[Both Dickinson and silence are, in a sense, banished and alone]

This stanza is difficult to parse. Cristanne Miller clumps this sort of syndetic writing (the repeated use of conjunctions) under parataxis (in that there are no subordinating conjunctions to guide our understanding). Is each ‘and’ meant to refer Ear, I and Silence back to ‘being’?—or is Dickinson imitating a sort of cumulative madness. My reading is that the latter is the case, but that two different states of being are described. In the first two lines she’s describing her experience consumed by the tolling bell. The second two liken that experience to being banished, wrecked and helplessly alone. She is banished. The Emily Dickinson Lexicon defines Race, among other definitions, as a “Course; journey; progression; steady movement toward a goal; [fig.] life; continued course of existence after death.” So Dickinson could be referring to her experience as a kind of ‘strange journey’. She could also be using “Race” in the sense of not belonging. If this is a spiritual crisis (a rejection of Christian theology) then she’s apt to feel as though she belongs to an altogether different “race” or society—wrecked/ostracized and solitary/alone. The same feeling may apply if her romantic overtures have been rejected. Her strangeness, her identity as an ambitious female poet, also could make her feel like an altogether ostracized “race”—and both interpretations could apply. One gets the sense that she wasn’t the kind of woman men pursued in those days.

And then a Plank in Reason, broke,

And I dropped down, and down -

And hit a World, at every plunge,

And Finished knowing - then -

And now, as usual with Dickinson’s final stanzas, things get interesting—very interesting. There are two very different ways to read this stanza. I think most, if not all, interpret this stanza as the threatened conclusion to the prior three stanzas. If Dickinson is describing the pain of a lost relationship, for example, then it makes sense to read this stanza as her descent into madness or nothingness. We interpret “plank” as a continuation of the imagery that associated the creaking floor with her soul and we might associate Reason with the Sense or sanity in the first stanza. In other words, her sanity and reason finally give way to madness. Her soul, the floor/plank upon which the funeral takes place, breaks or “breaks through”. She drops down and down. ‘World’, in this sense, might be her memories. In other words, every memory is a “world”. Once she has exhausted those memories, she is “finished knowing”. Even hearing is gone. (Interestingly, one will read that hearing is the last sense to die in a dying patient, but how scientists know this has never been explained.) The loss of her relationship, or hoped for relationship, is like a death to her. Vendler, who apparently can’t bear to kill poor Emily, describes the final lines as “leaving madness for a merciful unconsciousness”. But this poem would hardly be the first to suggest oblivion as the last word.

But let’s suppose the crisis is spiritual, then that makes an entirely different interpretation possible. A plank can also be “one of the separate articles in a declaration of the principles of a party or cause; as, a plank in the national platform.” This is not a possibility that you will find at the Dickinson Lexicon, but according to the Oxford English Dictionary, this understanding of the word plank appeared in poetry nearly a quarter century before Dickinson wrote this poem, as well as in Newspaper articles going back to 1848. That Dickinson, of all poets, would have been unaware of this meaning of “plank” is unlikely.

- In William Logan’s book Dickinson’s Nerves, Frost’s Woods, wherein Logan gives I felt a funeral a close reading, he credits Cynthia Griffin with the observation that “a telling emblem from the book Religious Allegories (1848), [shows] a gentleman crossing a plank that bestrides a dark abyss. The man holds a radiant book that must be the Bible, the plank is carved with the word “FAITH” and a shining mansion awaits his crossing.” [p. 260]

If “I felt a funeral in my brain” was prompted by a spiritual crisis, and we know, according to Richard Sewall, that Dickinson was greatly troubled by her refusal to join her peers in declaring Jesus as their Lord and savior. This wasn’t just a figurative refusal. There were repeated calls for her to join the revivals at Amherst.

It is in the sixth letter, written a fortnight later (January 31, 1846), that a New Year’s meditations come to a focus on spiritual matters. Save for a gossipy postscript, the letter, a long one, is entirely given over to religion. Emily confesses to Abiah that she did not become a Christian during the revival of the previous winter in Amherst. She has seen “many who felt there was nothing in religion… melted at once,” and it has been “really wonderful to see how near heaven came to sinful mortals.” Once, “for a short time,” she had known this beatific state herself, when “I felt I had found my savior.” “I never enjoyed.” she wrote, “such perfect peace and happiness.” But “I soon forgot my morning prayer or else it was irksome to me. One by one my old habits returned and I cared less for religion than ever.” At Abiah’s recent announcement that she was close to conversion, Emily “shed many tears.” She herself longs to follow after: “I fell that I shall never by happy without I love Christ.” But midway through the letter she makes a striking admission. a real bit of self-discovery. Putting aside the revival rhetoric, she seems to be speaking her own voice (even to the misspelling):

Perhaps you will not beleive it Dear A., but I attended none of the meetings last winter. I felt that I was so easily excited that I might again be deceived and I dared not trust myself.

This revelation is followed by a long passage on the dreadful thought of Eternity… [p. 381]

Knowing this, the meaning of “plank” takes on a whole new meaning. It’s not just a reference to her soul (which she earlier compared to the creaking floor) but a punning reference to the “plank” of Christian beliefs.

And then a Plank [an important principle on which the activities of a group... are based] in Reason [her own reasoning or the reasoning of others], broke,

And I dropped down, and down -

And hit a World, at every plunge,

And Finished knowing - then -

What does she mean by “hit a World” in this case? In Dickinson’s poem Bereavement in their death to fell, Dickinson offers us some possibilities. In the line ‘’tis as if Our souls/Absconded‘, she also considers the words World, selves and Sun for souls. In other words, these were all in some sense synonymous. Interestingly, the context is also similar, arguing that this is a sort of Dickinsonian image cluster.

- Certain images seem regularly to have led Shakespeare’s mind along a train of associated ones. Walter Whiter, in his Specimen of a Commentary on Shakespeare (1794), showed that flattery suggested dogs, which suggested sweetmeats. The phenomenon was more fully discussed by E. A. Armstrong in his Shakespeare’s Imagination: A Study of the Psychology of Association and Inspiration (1946), and is used by Kenneth Muir as evidence of authorship in his Shakespeare as Collaborator (1960).

So, with that in mind, Dickinson gives us at least two alternate readings for World—soul and self. And in that light, her hitting “a World, at every plunge” might refer to previous selves, or other versions of Emily Dickinson (like the Dickinson who had found her savior) until she finally gets through (got through in one revision of the poem) her “Knowing”. And what does ‘knowing’ mean? As it turns out, ‘knowing’ has a very specific meaning in Christian contexts. Look up the meaning of know and you will read that “knowing God is not simply an intellectual apprehension, but a response of faith and an acceptance of Christ.”

It is he who has made God known ( John 1:18 ).To know Christ is to know God ( John 14:7 ). Eternal life is to know the true God and Jesus Christ ( John 17:3 ). Paul desires to know Christ in his death and resurrection ( Php 3:10 ). Failure to know Jesus as Lord and Messiah ( Acts 2:36 ) resulted in his rejection and crucifixion ( 1 Cor 2:8 ).

To know Christ is to know truth ( John 8:32 ). While this is personal, it is also propositional. Knowledge of the truth ( 1 Tim 2:4 ; 2 Tim 2:25 ; 3:7 ; Titus 1:1 ) is both enlightenment and acceptance of the cognitive aspects of faith.

This knowing, this acceptance of Christ, is precisely what Dickinson could not accept. So, read in this light, what Dickinson might be saying is that the funeral in her brain is the rhetoric of proselytizing that already condemns her as dead to God and comes or threatens to bury her. The good Christians “mourn for her” and their mourning is like an endless treading that threatens to drive Dickinson to madness. Their “service” is like a drum that keeps beating, that won’t leave her in peace or silence. The culture of Christianity surrounding her cajoles, threatens, and proselytizes until she feels her mind going numb. Their insistence is like a drumbeat. Their boots (their own beliefs) are, to Dickinson, leaden. Their step is heavy on her soul and creaks under their weight. The religious imagery continues as she describes all the Heavens as a ringing bell, so pervasive that she feels herself reduced to a tortured ear. In another of her poems, she gives tongues to the bells and, in that sense, the bell is also proselytizing.

-

Isaiah 55:3

“Incline your ear and come to Me.

Listen, that you may live;

And I will make an everlasting covenant with you…

-

Matthew 13:16-17

But blessed are your eyes, because they see; and your ears, because they hear.

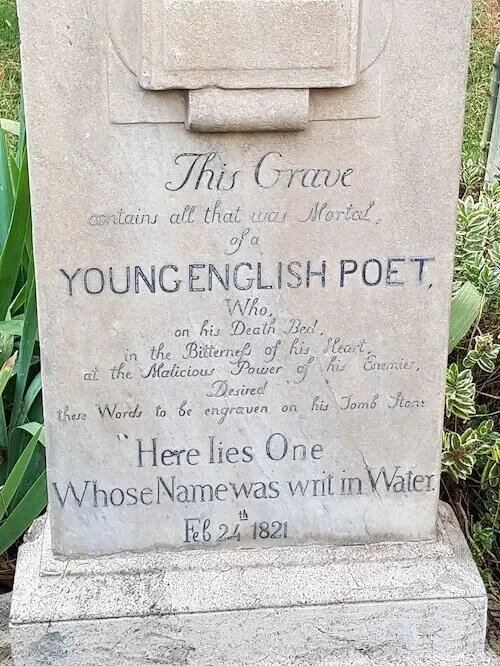

She, and her precious silence, are wrecked and solitary. As a fascinating side note, John Keats so despised the ringing of church bells that he wrote a sonnet on the subject:

Sonnet. Written In Disgust Of Vulgar Superstition

The church bells toll a melancholy round,

Calling the people to some other prayers,

Some other gloominess, more dreadful cares,

More hearkening to the sermon's horrid sound.

Surely the mind of man is closely bound

In some black spell; seeing that each one tears

Himself from fireside joys, and Lydian airs,

And converse high of those with glory crown'd.

Still, still they toll, and I should feel a damp,--

A chill as from a tomb, did I not know

That they are dying like an outburnt lamp;

That 'tis their sighing, wailing ere they go

Into oblivion; -- that fresh flowers will grow,

And many glories of immortal stamp.

This poem absolutely would have been read and known to Dickinson (note some of the interesting parallels—the drumbeat of Dickinson’s service, the horrid sound of Keats’s sermon; the melancholy round of Keats’s churchbells, the tortuous tolling of Dickinson’s bell; Keat’s damp chill, as from a tomb, and Dickinson’s funeral). Remember, from our previous discussion, that Dickinson put Keats at the top of her reading list during the same year that she wrote I felt a funeral.

And hit a World, at every plunge,

And Finished knowing - then -

The poem concludes with grim determination. The plank (the stated beliefs of their and/or her own reasoning) breaks under so much weight. She plunges through untold “Worlds” or selves or beliefs, her own and those of others, until she finally, as she wrote in one revision, gets or “got through”. She is finished with “knowing”—she will not accept Christ. And then the poem ends on the word then. This is where things get even more interesting. When Dickinson placed “I felt a funeral in my brain” in her fascicles, she followed it with ‘Tis so appalling — it exhilarates. Both poems were written the same year, and if we don’t know the reason Dickinson placed these poems next to each other, we know that she did. It is possible, for example to read “then” as leading directly into the next poem, such that both poems can be read as one:

(...)

And then a Plank in Reason, broke,

And I dropped down, and down -

And hit a World, at every plunge,

And Finished knowing - then -

'Tis so appalling — it exhilarates —

So over Horror, it half Captivates —

The Soul stares after it, secure —

A Sepulchre, fears frost, no more —

To scan a Ghost, is faint —

But grappling, conquers it —

How easy, Torment, now —

Suspense kept sawing so —

The Truth, is Bald, and Cold —

But that will hold —

If any are not sure —

We show them — prayer —

But we, who know,

Stop hoping, now —

Looking at Death, is Dying —

Just let go the Breath —

And not the pillow at your Cheek

So Slumbereth —

Others, Can wrestle —

Yours, is done —

And so of Woe, bleak dreaded — come,

It sets the Fright at liberty —

And Terror's free —

Gay, Ghastly, Holiday!

In this case, the word then is a transition to the next poem and the revelation that once the horror is past, the soul can “[stare] after it, secure”. But let’s say that Dickinson did put these two poems together meaning them to be read together. She still does the unexpected. ‘Tis so appalling (as discussed earlier) is more sarcasm, scorn and contempt, than celebration. If one reads ‘Tis so appalling as a companion poem, then I felt a Funeral, in my Brain is Dickinson refusing to accept Christ while ‘Tis so appalling — it exhilarates — is her sarcastic, darkly humorous riposte, saying, Great! “Gay, Ghastly Holiday!” Now what? She has escaped the leaden boots of Christian dogma, to believe in what?

One might object by saying that if these two poems are meant to be read as one, then why not every poem in her fascicle? That’s a fair objection but, conversely, she didn’t just roll the dice. The whole point of the fascicle, after all, was to arrange the poetry. It’s not far-fetched to assert that the reason these two poems are together is that, for Dickinson, they were associated.

Which interpretation do I prefer? If the poem is about a disappointment in love, friendship or her disappointment as an artist, then we’re greeted with a poem that conveys her suffering through analogy with the Christian rituals of burial. Her suffering is like a funeral. The persistence of the suffering and weight of it is like the leaden tread of the mourners. Heaven in her poem is not the heaven of paradise but the remorseless tongue of dogma, the church bell, ostracizing her, rejecting her, driving her to desperate madness. The service meant to offer solace and comfort is a brutal and annihilating drumbeat. Even if Emily Dickinson is not having a spiritual crisis, Emily Dickinson’s imagery is.

Lastly, Sewall credits Ruth Miller with identifying I felt a Cleaving in my Mind— as a variant poem of I felt a funeral.

I felt a Cleaving in my mind —

As if my Brain had split —

I tried to match it, Seam by Seam —

But could not make them fit —

The thought behind, I strove to join

Unto the thought before —

But Sequence ravelled out of Sound —

Like Balls — upon a Floor.

[FR867/J937,J992]

Similar themes appear, though without the oppressive Christian rituals. The poem is said to be written in 1864, two years after I felt a funeral. I know I’m treading on sacred ground with leaden heels, but compared to the former, this poem feels more like the product of a doodle taken from one of her envelope poems—as though the conceit occurred to Dickinson and she ran with it. That’s not to say that the poem doesn’t succeed, just that it reads as though it’s eight parts “art” and maybe two parts “autobiography”. The impression is made more so with the revision she later sent to Susan Dickinson:

The Dust behind I strove to join

Unto the Disk before —

But Sequence ravelled out of Sound

Like Balls upon a Floor —

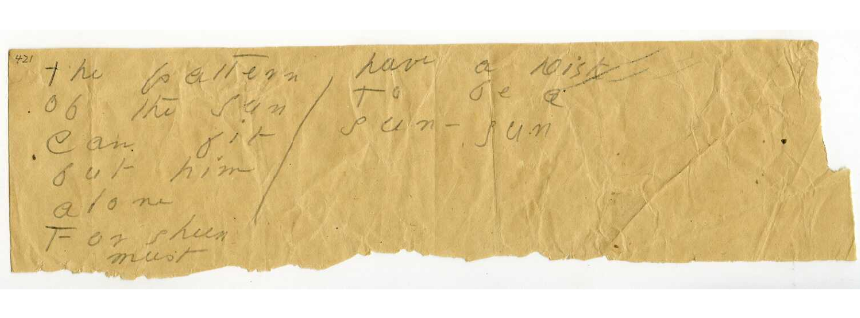

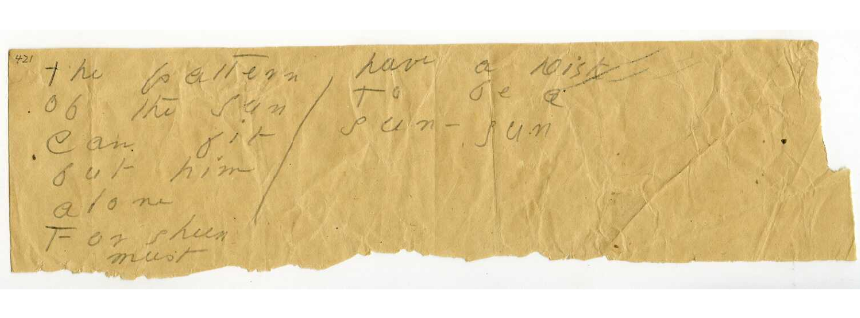

What I like about the revision is what it reveals as regards Emily the artist and craftsman. She wasn’t just an instinctive genius, but a thinking and discerning artist perfecting her craft. Sure, there is a portion of her poetry that are her letters to the world—but I would argue that a portion are also the product of a craftsman, someone to whom metaphors and analogies came easily, along with the ideas usefully expressed by them. Her first version—”thought behind, I strove to join/Unto the thought before“—effectively communicates the central idea, but “a thought” is an abstract thing. Like any poet/craftsman, she knew that a poem lives or dies in its imagery, its power to evoke through figurative language and the five senses. The fragments of the poem’s thoughts don’t just roll out of reach (her first version), but ravel out of Sound. So, she added specificity to the thoughts. The thought behind becomes dust and the thought before becomes the Disk. “Ashes to ashes, dust to dust” explains “the dust”, but what is the Disk? Vendler interprets Disk as “the Sun of sunrise”, symbolizing a new beginning, and I think she’s right. She quotes Dickinson’s four line poem “The pattern of the sun”, as evidence for her interpretation:

The pattern of the sun

Can fit but him alone

For sheen must have a Disk

To be a sun —

So anyway, whereas I felt a funeral reads like a poem arising from a real crisis, I felt a Cleaving reads more like a work of art—to me.

Amherst MA

Amherst Manuscript # 421

Amherst – Amherst Manuscript # 421 – The pattern of the sun – asc:7785 – p. 1