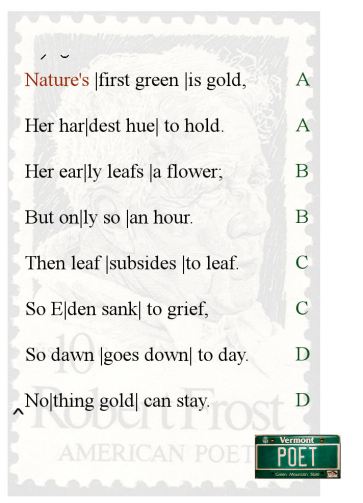

Nature’s first green is gold,

Nature’s first green is gold,

Her hardest hue to hold.

Her early leafs a flower;

But only so an hour.

Then leaf subsides to leaf.

So Eden sank to grief,

So dawn goes down to day.

Nothing gold can stay.

Similar to my post on “Stopping by Woods”, I’ll take a look at how different authors have analyzed the poem (and mix in my own 2¢ along the way). We’ll also look at the history of the poem, how it arrived at its final form — a subject almost as interesting as the poem itself.

Nothing Golden Stays

The aspect of the poem that nearly all close readers and critics emphasize is Frost’s use of paradox and his reference to Adam & Eve – the Christian creation myth. The story of Adam & Eve is sprinkled throughout western art, literature and music and any artist who references the story also inherits a wealth of associations.

Aside: When I was a high school junior at Western Reserve Academy, my English teacher expressed the opinion that the story of Adam & Eve was a profoundly inspired story. I countered that the story was actually stock and trade, no more inspired than any other creation myth. If looks could kill. He chalked it up to teen-aged diffidence but my opinion hasn’t changed. He asked if I could name any other story that was so pervasive. Like in China? I countered. That ended the discussion. My 2¢? Take any fable, be it ever so humble, make it the centerpiece of your culture’s spiritual and religious identity for hundreds of years and watch it flourish. It’s the centuries of art and literature, like variations, that burnish the fable of Adam & Eve. Think of Beethoven’s Diabelli variations. There’s nothing special about Diabelli’s little theme. It’s Beethoven’s variations, based on the theme, that burnish the original.

But back to Robert Frost. Frost adds considerable depth by alluding to Adam & Eve. The subject matter of the poem is elevated from a wistful observation on the passage of time to a more  universal comment encompassing time and creation itself. Such is the power of alluding to the myth. Alfred R. Ferguson, in an essay entitled “Frost and the Paradox of the Fortunate Fall“, begins the essay as follows: “Perhaps no single poem more fully embodies the ambiguous balance between paradisiac good and the paradoxically more fruitful human good than “Nothing Gold Can Stay,” a poem in which the metaphors of Eden and the Fall cohere with the idea of felix culpa.”

universal comment encompassing time and creation itself. Such is the power of alluding to the myth. Alfred R. Ferguson, in an essay entitled “Frost and the Paradox of the Fortunate Fall“, begins the essay as follows: “Perhaps no single poem more fully embodies the ambiguous balance between paradisiac good and the paradoxically more fruitful human good than “Nothing Gold Can Stay,” a poem in which the metaphors of Eden and the Fall cohere with the idea of felix culpa.”

And yet, for all this, the first version of the poem doesn’t include a reference to the Bible. The very first version was, in fact, nothing more than a wistful observation on the passage of time.

Nature’s first green is gold,

Her hardest hue to hold.

Her early leaves are flowers—

But only so for hours;

Then leaves subside to leaves.

In autumn she achieves

Another golden flame

And yet it’s not the same

It[‘s] not as lovely quite

As that first golden light.

Here’s my theory on Frost’s thought process. The version above, the earliest, is also the most forgettable. The first five lines are clearly the strongest and he probably thought of them all in one sitting. After that, though he recognized their promise, he didn’t know where to go with them. The last five lines are anticlimactic. They don’t elevate the subject matter and present no new ideas.

For example: Gold appears in the first line only to be repeated twice (in lines 6 and 10) as a weaker adjective. Not only that but there’s really no difference between a “golden flame” and a “golden light“. Not knowing what he wants to say, Frost is merely killing space. Adjectives, in poetry, can easily indicate second rate thought, second rate poetry, and a second rate poet. Frost repeats ideas anti-climatically. By writing that autumn “achieves another golden flame” he’s already given away the game. By the time he calls nature’s first “gold” a “golden light” there’s no surprise or elevation in thought. There’s no epiphany or feeling of development. The phrase And yet it’s not the same adds nothing. It’s little more than rhetorical filler for the sake of rhyme.

But Frost wasn’t a second rate poet. He recognized the sententious weaknesses in this first version. He moved on. He revised.

Nature’s first green is gold,

Her hardest hue to hold.

Her early leaves are flowers—

But only so for hours;

Then leaves subside to leaves.

In autumn she achieves

A still more golden blaze

But nothing golden stays.

[From Selections from American literature, edited by Leonidas Warren Payne p. 936]

This revision, this much of it, is a clear improvement. He’s gotten rid of the phrase And yet it’s not the same. He’s tightened the poem by reducing it from ten lines to eight. The final four lines become a mirror image of the first four. In effect, he’s created a volta such as you would find in a Sonnet – a turn or change in the subject, a movement from proposition to resolution.

But problems remain. Golden, as in the first version, is repeated twice, diminishing the epithet’s effectiveness. But that’s the least of it. Changing the noun gold into the adjectives golden remains the first sin. The problem is that the emphasis is on blaze and stays rather than gold. The image left in the readers mind is diffuse. What does a blaze look like?

However, this isn’t the end of the poem. Here is the earlier version of the poem in its entirety. This marks the first time this version has appeared anywhere on the world wide web. I don’t know why scholars (and if you’re a scholar I’m talking to you) can’t be bothered to print the entirety of the poem if you’re going to discuss it. I had to reconstruct this from snippets and fragments gleaned from deviously clever Google book searches. Here it is:

Nothing Golden Stays

Nature’s first green is gold,

Her hardest hue to hold.

Her early leaves are flowers—

But only so for hours;

Then leaves subside to leaves.

In autumn she achieves

A still more golden blaze

But nothing golden stays.

Of white, blue, gold and green,

The only colors seen

And thought of in the vast,

The gold is soonest past.

A moment it appears

At either end of years,

At either end of days.

But nothing golden stays.

In gold as it began

The world will end for man.

And some belief avow

The world is ending now.

The final age of gold

In what we now behold.

If so, we’d better gaze,

For nothing golden stays.

This isn’t bad, but it seems excessive for a wistful poem about the passage of time. The second stanza more or less elaborates on what was already implied by the first stanza. My guess is that Frost thought the poem would feel weightier having a tripartite form. The problem, as Shakespeare put it with characteristic genius, is that “He draweth out the thread of his verbosity finer than the staple of his argument.” There are more words than matter in this poem.

But why is Frost looking for a weightier poem and what’s the third stanza about? Tyler Hoffman, in his book Robert Frost and the Politics of Poetry, explains (though, like other authors, he couldn’t be bothered to provide the entire poem):

…Frost is speaking out on international political affairs in his sly way, and it is important to remember that this poem is composed in 1920, just after World War I has ended. Feeling sure that “there are two or three more wars close at hand,” Frost expresses a fierce nationalism at this time and, with it, an isolationist political position (…) ” Nothing Gold Can Stay” tropes this position, suggesting through its isolation of syntactic units a refusal to become embroiled in global politics: just as Nature tries to resists the forces of change, so America must try to resist forces that would pull her beyond her borders, even if such resistance may be in vain. That the poem originally included lines that later became part of “It is Almost the Year 2000,” (…) points to another political meaning, as Frost jabs at 1930s liberals who believe that the millenium is upon us on the evidence of the terrible times. [pp. 162-163]

• Hoffman makes observations about the poem’s form that I don’t find persuasive. He remarks that “it is seemingly ironic that the boundaries of phrasal units and lines should match up so neatly in a poem about transition, the change from one season to another.” Hoffman’s answer to this perceived conundrum is that “through tight closure, Frost is able to depict the effort on Nature’s part to ‘hold’ — to try to resist the forces of change that inevitably will overpower her.” He then goes on to note that the earlier version of the poem does not follow this pattern. One would think this would fatally undercut Hoffman’s assertion, but he nicely pirouettes: “In this draft version, hard enjambment also is resisted, a formal condition that reads as an emblem of Frost’s political resistence to socialist utopian thought.”

Say what? Hoffman gives us no citation for these assertions. Did Frost, at some point, characterize his use of end-stopped lines and enjambment as political “emblems”? No. So, what we’re left with is Hoffman’s opinion as to what Frost was thinking. I don’t buy it. I’m not persuaded. If anything, this kind of analysis smacks of David Orr’s Enactment Fallacy. I’ve linked to Orr’s article a dozen times in other posts, but if you haven’t read it then it’s worth reading or reading again. Orr writes of the Enactment Fallacy:

Basically, this is the assignment of meaning to technical aspects of poetry that those aspects don’t necessarily possess. For example, in an otherwise excellent discussion of Yeats’s use of ottava rima (a type of eight-line stanza), Vendler attributes great effect to “the pacing” allegedly created by “a fierce set of enjambments” followed by a “violent drop” in the fourth stanza of the poem “Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen.

Hoffman, like Vendler, is imposing meaning on poetic techniques. If one takes Hoffman at his word, are we then to conclude that every example of enjambment is politically emblematic? If not, then we’re cherry picking. Otherwise we must be willing to say that enjambment means X in this poem, but Y in that poem without any evidence whatsoever. Unless you’ve heard it from Frost, don’t be persuaded by assertions like these.

Getting back to the poem’s theme, I am persuaded by Hoffman’s thinking that the original impulse for “Nothing Gold Can Stay” developed into something political. This explains, perhaps, why Frost wanted a weightier poem in three parts. What may have began as a wistful nature poem began to be seen, by Frost, as a good metaphor for his disagreement with liberal politics (“some belief avow”), which he perceived as Utopian – hence golden.

With that in mind, we can discern the first appearance of Adam & Eve. “In gold as it began…” he writes. That is, mankind began in gold, in the Garden of Eden. If gold is then a euphemism for utopianism, then the Garden of Eden is the ultimate tale of liberal utopianism. I’ve read some other analyses of Nothing Gold Can Stay by other bloggers who see in Frost’s allusion a sympathetically Christian one; but, if anything, Frost’s initial allusion to the Garden of Eden is anything but sympathetic. His allusion almost drips with sarcasm. ‘You see how long that lasted,’ he seems to say. What makes you think this new Democratic and socialist utopianism is going to fair any better? If that’s what you think, he writes at the close of the poem, then you’d “better gaze [now], For nothing golden [Utopian] stays.”

With that in mind, we can discern the first appearance of Adam & Eve. “In gold as it began…” he writes. That is, mankind began in gold, in the Garden of Eden. If gold is then a euphemism for utopianism, then the Garden of Eden is the ultimate tale of liberal utopianism. I’ve read some other analyses of Nothing Gold Can Stay by other bloggers who see in Frost’s allusion a sympathetically Christian one; but, if anything, Frost’s initial allusion to the Garden of Eden is anything but sympathetic. His allusion almost drips with sarcasm. ‘You see how long that lasted,’ he seems to say. What makes you think this new Democratic and socialist utopianism is going to fair any better? If that’s what you think, he writes at the close of the poem, then you’d “better gaze [now], For nothing golden [Utopian] stays.”

He taunts liberals (and socialists) for their Utopian vision of society by bitingly comparing it to the Utopian vision of Christian Theology – the End Days, End Times or the Second Coming. He calls it the “final age of gold”. Is it accident that he uses the very phrase?

A moment it appears

At either end of years,

At either end of days.

But nothing golden stays.

Frost’s skepticism applies not just to the Garden of Eden, but to the reputed gold age that will come with Christ’s Second Coming. Just as in the first instance, he writes, it won’t stay.

So much for a wistful nature poem.

But there’s a reason why this earlier version is so hard to find. It’s not that good. As with all political poems, it comes stamped and dated. Political poems have short shelf lives. Without knowing the political impetus behind the original poem, the whole of it comes off sounding excessively verbose. Frost must have recognized the limitations of the poem and how his politics circumscribed the poem’s potential universality.

He went back to work. He revised.

Nothing Gold Can Stay

I find the differing versions of this poem revealing as to Robert Frost’s personality. It’s easy to sense, in the earlier version, a side of Frost that was ill-humored, sarcastic, acerbic and dismissive. It’s a darker undercurrent that can be sensed in many of his poems and one, as revealed in many of his sketches, that he tempers. Nothing Gold Can Stay is a perfect example. The final version is deceptively straightforward, like many of Frost’s poems, but the tincture of Frost’s acerbic personality remains, adding depth and perspective to what, otherwise, might simply be mawkish.

Frost quickly dispenses with the second stanza. One might not think it at first glance, but it’s easy to read a dismissive tone into the first four lines of the second stanza:

Of white, blue, gold and green,

The only colors seen

And thought of in the vast,

The gold is soonest past.

There are other colors (politics) besides gold, but no one else “in the vast” seems to see them. Without the political impetus behind these lines, they have the potential to sound petty. The lines also state what is already understood. The subject of the poem, in a sense, pertains to what is golden. The fact that the other colors are overlooked is already implied.

The third stanza gets the ax because it threatens to come off as nothing more than derisive political posturing.

This brings Frost back to the first stanza. Eden is still buzzing in his brain. He realizes that this reference has the potential to expansively elevate the subject matter – a facet missing in the earliest versions. Frost returns to the first four lines but this time changes flowers to the more universal flower. The singular flower carries a more symbolic feeling than flowers. Likewise, the change from hours to hour gives the word a more universal, symbolic flavor.

Frost alters his poem from naturalistic generality to symbol. A flower could be anything (whereas flowers will be more generally read as flowers). From there, and with Eden still in the back of his mind, he makes the leap to the next four lines:

Then leaf subsides to leaf.

So Eden sank to grief,

So dawn goes down to day.

Nothing gold can stay.

Rather than use a euphemism, Frost simply writes Eden — Eden sank to grief. But a tone has been set. By Frost’s use of the singular flower, hour and leaf, the reference to Eden becomes a symbolic gesture which, because of its suggestive power, smoothly elevates the poem’s thought and philosophic reach. The idea of Eden burnishes the word dawn, imbuing it with a deeper symbolism. But there’s something more to this line, the idea that dawn goes down to day. More than one author and critic has sought explanation in the Latin phrase felix culpa or blessèd fall. This is the paradoxical concept that through diminution or decay comes increase and growth. The day is the apogee of sunlight and warmth, but to have that day, the beauty of dawn must go down. The dawn itself, like the first green of the early leaf is a kind of gold that must go down before the leaf can bear fruit. Nothing gold can stay. As King Midas learned, gold that stays makes for a lifeless world.

Alfred Furgeson, whose Frost and the Paradox of the Fortunate Fall I quoted earlier, nicely sums up the same ideas in his own way:

It is a felix culpa and light-bringing. Our whole human experience makes us aware that dawn is tentative, lovely, but incomplete and evanescent. Our expectation is that dawn does not “go down” to day, but comes up, as in Kipling’s famous phrase, “like thunder,” into the satisfying warmth of sunlight and full life. The hesitant perfections of gold, of flower, of Eden, and finally of dawn are linked to parallel terms which are set in verbal contexts of diminished value. Yet in each case the parallel term is potentially of larger worth. If the reader accepts green leaf and the full sunlight of day as finally more attractive than the transitory golden flower and the rose flush of a brief dawn, he must also accept the Edenic sinking into grief as a rise into a larger life. In each case the temporary and partial becomes more long-lived and complete; the natural cycle that turns from flower to leaf, from dawn to day, balances each loss by a real gain. Eden’s fall is a blessing in the same fashion, an entry into fuller life and greater light.

It’s worth pointing out, at this point, that the poem’s political implications were still probably present in Frost’s mind and in his later readings, but they no longer feel like the poem’s primary impetus. He accomplished this, in part, by his more symbolic use of language. The poem, if construed as political, is no longer an ascerbic dismissal of a political belief, but an elegant alternative to those beliefs. Rather than simply mock a system of beliefs he disagrees with, he offers an alternative. The decline (or failure) of utopianism is an inevitable outcome if the cycle of life is to be respected and appreciated.

This revision makes the poem interestingly and compellingly constructive rather than destructive. The necessary tension between creation and destruction is what makes the poem great. At the same time that we feel the loss of all that is gold, we also sense the necessity and blessèdness that comes from that loss.

The Poem’s Form

The poem is written in Iambic Trimeter. The only variant feet are a trochaic foot in the first line and a headless foot in the final line. The headless foot in the final line is especially effective. To my ears, it adds a succinct pithiness to the final line, like a sonnet’s epigrammatic close.

There’s another longer and more detailed (read deep) look at how this poem works at an aural/linguistic level by John A. Rea. The analysis can be found here. It’s a fascinating attempt to do what is nearly impossible – describe what is musical about the language in the poem. It’s almost like trying to describe the color red to a blind man. You can decide for yourself whether he succeeds or is even readable, but I admire and appreciate the attempt.

Coda

- Curiously, a number of bloggers have posted a strange hybrid. You will sometimes find the following:

Nature’s first green is gold,

Her hardest hue to hold.

Her early leafs a flower;

But only so an hour.

Then leaves subside to leaves.

So Eden sank to grief,

So dawn goes down to day.

Nothing gold can stay.

The problem is that the word leaves doesn’t rhyme with grief. That’s not anything Frost would have written. That’s just a mistake. You will also find the title, sometimes, mistakenly given as Nothing Golden Stays. This title, in fact, belongs to the earlier version.

Thank you. I have read this poem as part of a eulogy for friends, and I believe Frost was commenting on man’s struggle against evil on some level. A true genius can take a complex subject and state it simply which is what Frost has done. I can’t thank you enough for your sedulous work. Your analysis will keep me involved reading poetry for another month.

LikeLike

You’re welcome, Mike. And thank you for reminding me of the word sedulous. It’s been years! Now I’m going to have to use it in a conversation.

LikeLike

the poem is about death and loss….nothing good can last, everything goes bad and falls away. he was in his 50’s when he wrote this and this kind of subject is what is normal to think about at that age.

ive never seen the other versions and i thank you for sharing.

LikeLike

Thanks, j.b.. You’re right. The poem, among other things, is about death and loss.

LikeLike

At the time he had written this, he had lost 2 children, both his parents, and his closest friend. So it would make sense that he would be thinking and writing about grief and change after loss.

LikeLike

Very likely so. Hard to see how such circumstances might not have affected how he revised the poem.

LikeLike

This was all very interesting — I never would have guessed that Forst would have done so many revisions of a poem. BTW — The poem I confused that with was “A Passing Glimpse” Another of Frost’s better poems.

LikeLike

this is very interesting…and very sad…im researching him

LikeLike

Why do you find it sad?

LikeLike

Hi Chrystian, no other poem of Mr. Frost has made me think deeply about the man and his work. Frost was criticized for being shallow, yet he won awards that his critics did not. Frost was committed to using every day activities to make commentary on the deeper meanings. I don’t think he was alone in this view. The native Americans would say, “You don’t ever own anything” and growing up, I heard, “Only the good die young.” Good luck in your work.

LikeLike

Pingback: Favorite Robert F poem | yorosa

this is a good poem

LikeLike

My only issue is this, “So dawn goes down to day.” Dawn turning into day is a positive thing, not a negative thing like the theme of the poem.

LikeLike

//Dawn turning into day is a positive thing, not a negative thing…//

But the art of great poetry is to make us see the world in unexpected ways. Nothing would be more expected, or clichéd, than to portray dawn’s turning into day as positive. Dawn, in the context of the poem, is the most beautiful part of the day — full of youth, color, expectation and potential. :-)

LikeLike

Not as beautiful as the day is. I would humbly suggest a couple changes:

Nature’s first green is gold,

Her hardest hue to hold.

Her early leafs a flower;

But only so an hour.

Then leaves subside to leaf. (the many descending down to a lone one)

So Eden sank to grief,

So dawn goes down to gray. (gray suggesting the coming darkness, also alludes to old age)

Nothing gold can stay.

LikeLike

Okay, that’s not bad, but then you miss the suggestiveness of one leaf subsiding to another that has already fallen. Frost’s imagery is more concrete than yours; yours more abstract.

Your emendation is problematic in that not all days are gray, and so you give up some of the original line’s universality. That is, dawn will always go down to day but will not always go down to gray. So, you change the poem from a universal experience to a particularized and personal experience. Secondly, and as with your first emendation, you change the concrete imagery to an abstraction. “Day” is concrete. “Gray” is an abstraction (in that gray could refer to any number of things) and so your change makes the imagery more diffuse and weaker. Concrete imagery is nearly always preferable to abstraction. Thirdly, your emendation is expected. There’s nothing that gives the reader pause, the way Frost gave you pause — forcing you to either accept and rethink your conception of dawn, or reject it. Either way, Frost’s line retains a more forceful effect than the emendation. :-)

LikeLike

“That is, dawn will always go down to day but will not always go down to gray.”

lol, no all days turn to night/black thus just before nightfall we have duck/gray.

I think the revisions strengthen the poem and I think Frost would receive the suggestions better than you might think. I write and I have changed poems when a friend of mine made good suggestions.

LikeLike

Final suggestion (changed last line to match the others):

Nothing gold can stay.

Nature’s first green is gold,

Her hardest hue to hold.

Her early leaf’s a flower;

But only so an hour.

Then leaves subside to leaf.

So Eden sank to grief,

So dawn goes down to gray.

So, nothing gold can stay.

LikeLike

Each line is now 6 syllables. All lines rhyme perfectly. Leaf matches the first mention of a leaf, Gray hinting at old age and the loss of the day, Adding So to last line also more strongly affirms the title’s claim after proving it through the earlier lines.

I only wish Frost was still alive…

LikeLike

Well, you’ll be pleased to know you stand proudly in a long line of towering revisers, editors and poets — nay, household names — like D’Avenant, Tate, Shadwell, Ravenscroft, Crowne, Granville, Burnaby, Otway, Cibber, and D’Ufrey, all of whom greatly improved Shakespeare by regularizing his meter and tidying the transparency and decorum of his imagery.

Shakespeare’s original attempt:

Vastly improved by D’venant

I mean, why stop with Frost? Put your hand to Shakespeare and we can all wish that Shakespeare were also alive…

LikeLike

There is no reason to act that way. This is intended to be a mature discussion about a poet and his work. To suggest changes is not an offense to anyone. Movies are re-done and often are better the second time around. This is no different.

LikeLike

//Movies are re-done and often are better the second time around. This is no different.//

I’m sure the aforementioned poets would have completely agreed with you. Take comfort, your improvements withstand comparison to any of theirs. :-)

Edit: You might (or might not) appreciate the following book: Shakespeare Improved by Hazelton Spencer

LikeLike

Hello! Well this is awkwardly two years late but I was hoping to use some of your insight in an English essay I’m writing about the poem:) You have been properly cited and I would be more than happy to send you the part of the essay in which you are mentioned, or the entire thing if you like. To be clear, I’m not using your thoughts as my essay, I’m simply citing some of the facts you mentioned about him reworking the poem as proof for one of my claims. Thanks :)

LikeLike

Hi Sydney, all these posts are current (you’re not two years late); and I’m glad the post was helpful.

That’s why I write them. :)

You’re more than welcome to use any of my ideas as a springboard. That’s what I do in my own posts. I’ve borrowed many ideas to elaborate on them (and have always tried to give credit where credit is due). There’s nothing wrong with that in my view. If you’d like to send along something you’ve written for a second opinion, I’d be happy to look at it.

LikeLike

Thank you very much! I wanted to mention just so you know how and why your work was used. I’m finished now so no second opinion needed but thanks:) Was just going to send if you needed reassuring but you seem comfortable and generous with my citing it so I’ll just thanks again!

LikeLike

I’ll still love to read it if you’re willing. I get thousands of students visiting each week and have always wondered what kinds of papers they’re writing. I don’t need to but if you’re game, I’d enjoy it. :)

LikeLike

Wow I thought this would be a good article but I couldnt get past your athiesticle attitude toward Adam and Eve. Who were actual people and if they were not then we would not be around. FYI The Bible KJV is the most referred to History Book in the World. And it is True Not a Myth. Maybe you should read it and find out the truth. Or just try to prove it wrong on your own because many have tried and have become believers. Jesus Came an Innocent Man and Died For all mans sins and if you believe and ask him you will be saved. I am so tired of people who have never read the Bible telling my kids that everything I am teaching them and preaching is a myth. Well if you dont want eternal life fine. Now you cant say you never heard the truth so if u dont believe you will just go to the lake of fire with all the other evilutionist Including Darwin. Oh by the way Darwin and Yale have said the theory of evolution is false and that my friend is a myth. Jesus Loves You and I hope you get saved and turn to the truth.

LikeLike

If whatever you believe in helps you to be a good person, then I’ve no quarrel with that. :)

LikeLike

I spent a lot of time outdoors in my coming of age years – hiking, camping, etc. As I was making meaning of the world, one of my favorite times of day was that early morning time before dawn. I still love that first hour before the sun actually comes up. If you sit outside, you can see the black silhouettes of the trees and hills slowly change. The fun thing is – they don’t suddenly turn into real colors. Instead, you get a slow transition from black to something else, something surreal, before you get true colors. In that brief time, you can make out a fencepost to be a figure, or a leaf to be a flower, or a rock to be an animal. And the pigments evolve. Look away and look back and the hue is different. This marvelous and vague world only last a short time before the rising sun snaps everything into its normal shape and color.

So, as a teenager, when I came across Frost’s “Nature’s first green is gold, her hardest hue to hold…” I knew exactly what he was talking about: that strange subtle gold that tints the earth before the “real” colors break forth. And for many mornings in the last 40 years, those lines come to mind when I am up before dawn and looking out at the world.

This morning, after watching this dance of shaded washes – always the same and always new –decorate the hills outside my window, I decided to find the rest of the poem on the Internet. So I came across your analysis along with dozens of others.

And NONE of them related this word picture to the hour before dawn! Most of them think the first green has to do with spring (hey – have you looked at spring? The first greens are lighter, maybe lime green or yellow-green, in the spring, but they aren’t gold!). I’m thinking, “do all these academics live in apartments without windows or cities without vegetation?” Frost obviously spent a lot of time outdoors in order to have “woods are lovely dark and deep” or “leaves no step had trodden black”. Yet these people who are analyzing his poetry don’t seem to “get” his world and his word picture in this poem!

I did like your printing of earlier versions. I can totally understand why Frost added the “oh yeah, there is another gold in nature, it comes in the fall”, and then rejected that image. It is much too brazen of an image to hold up against pre-morning’s fay elusiveness.

Yes, you can analyze this poem to be about the briefness of life, or the fall, or politics, or many other things. But if you can’t relate to the amazing yet delicate odd gold-ness of the minutes when the sky gradually lightens, how are you going to “get” the poem?

I suggest that anyone trying to understand this poem (whether college professor, poet or student) to get up before sunrise in a place where there is some “nature” out your window, and watch the play of colors. You will see that the greens briefly aren’t green, but gold. The leaves might be flowers or fairies briefly before you can tell what they really are. And then dawn goes down to day…

LikeLike

I like your reading of the poem, and why not? I would be wary, though, of asserting that this is what Frost meant — only because we ultimately don’t know what Frost meant. We only have the various sketches and the final poem. I think you’re absolutely right to read the line “So dawn goes down to day” this way, but as I read Frost’s earliest version, for instance, it’s clear that he’s using “gold” figuratively to refer to Spring’s first green mainly because he contrasts that with “autumn” when “she achieves/ Another golden flame”. If he were just describing the first light of morning, then there would be no reason “nature” couldn’t accomplish the same in autumn, winter or summer—especially summer. So, yes, he absolutely describes that moment that you describe when “dawn goes down to day”, but that is secondary, I’d say, to the description of nature’s “first green” being gold.

And as to this:

“The first greens are lighter, maybe lime green or yellow-green, in the spring, but they aren’t gold!)”

I first would say that Frost is using the color “gold” figuratively, not literally. Second, not being an academic or living in a house without windows (too many actually—and hard to heat), but in the mountains of Vermont, I disagree. Nature’s first green isn’t her leaves, but her buds, and they can indeed take on a golden hue but, as Frost says, they hardly last a day before going to leaf. But allowing for that, Frost also suggests that the early leaf may be a flower, and a flower may most certainly look golden no matter the time of day.

So I guess I would say, what a wonderful way to read the poem; but if you want Frost to agree with you, that might be a little tougher. :-)

LikeLike

Hmm, someone is very anti religion, or, really just anti- Christian, and extremely prideful of there rather non-impressive achievements. Thank you though for a wonderfully worded article, very careful to twist the world into some sarcastic variation of your values. I rather enjoyed you trying.

LikeLike

Frost was deeply skeptical of any sort of utopianism, as am I, but I don’t know that he was “anti-religion” or “anti-Christian”. He was typically cagey about his beliefs, calling himself, at times, an old testament believer. At other times he seemed to suggest some atheism. My own suspicion is that God was too convenient a metaphor for the poet to give up. Having a somebody, even God, to square up against was worth more to him that having nothing or no one. His wife as an avowed atheist. Made so, possibly, by the death of their first child (his poem ‘Home Burial’ is probably derived from that experience). As for me, Christianity is simply another mythology. One among many. I am only anti-religious insofar as religion permits cruelty, tribalism, intolerance and bigotry. Inasmuch as religion encourages the best in humanity, any religion can be beautiful and equally valid. All religions are spiritual metaphors.

LikeLike

Excuse me but, in the first sentence when it says that Adam and Eve are a Christian creation myth… I think not. I refuse to believe that something exploded in space and that is the reason I am alive or anything is alive or how trees can give us oxygen to breathe. Absolutely pathetic.

LikeLike

You may refuse to believe or believe whatever you like. Most every religion has its own creation myth, including Christianity, and the adherents of each believe their mythologies just as fervently.

LikeLike

Pingback: Robert Frost’s “Nothing Gold Can Stay,” revisited | Richard Subber

Pingback: “Nothing Gold Can Stay” by Robert Frost - writingaidservices