My New Favorite ‘Complete’

This post was requested by Melissa. She asked me to provide a scansion, but I can’t just scan a poem and not talk about.

I’m sure a few upper lips in academe will be horrified by the title of my post but, let’s not kid ourselves, when we boil down Donne’s fifth  Holy Sonnet, we get the anguished guilt-trip of a penitent. Such is the power of a great poet, and such was the power of King James English, that Donne could turn an ostensibly confessional poem into, if not a masterpiece, a compelling work of literature.

Holy Sonnet, we get the anguished guilt-trip of a penitent. Such is the power of a great poet, and such was the power of King James English, that Donne could turn an ostensibly confessional poem into, if not a masterpiece, a compelling work of literature.

Anyway, I think this post was meant to be. While I was noodling around on Christmas Eve’s Eve at a Montpelier used book store, I discovered another complete collection of Donne’s poetry. Now I have three. This one comes from The Anchor Seventeenth-Century Series and is edited by John T. Shawcross. This particular edition, printed in 1967 (and in a becoming shade of pink) is now my favorite. It may be out of print. The reason it’s my favorite is because Shawcross ‘gets’ the importance of spelling and punctuation in Elizabethan poetics. H.J.C. Grierson, the editor of the two volume gold-gilt Oxford edition glosses over the punctuation in crucial places. Even my former favorite, the Everyman edition edited by C.A. Partrides, doesn’t quite get it right. The Norton “Critical” Edition (air quotes), is useless. Don’t get me started. Donne’s metrical practice isn’t all that difficult if we preserve the spelling and punctuation. Donne did not intend his poetry to be difficult. He gave us all sorts of clues. Here’s how Shawcross sums up his editorial practices in relation to the crucial question of Donne’s orthography.

[T]he danger of a plethora of so-called scholarly texts is present, but a revision of Grierson’s, eschewing certain misreadings which often seem to have arisen from delicacy and certain modernizations which obscure subtleties, has long been needed. (…) ¶ The practice of inserting an apostrophe to indicate elision has generally been followed. It is consistently followed in preterits and participles where “e” would create another syllable. 9e.g. “deliver’d,” (…) , in combinations of “the” and “to” where the vowel is not pronounced (e.g. “the’seaven,” (…), and to’advance,” (…), and in the coalescing of two contiguous vowels from two different words (e.g. “Vertue’attired,” (…), which is given three metrical beats.) In the latter case the vowels are really pronounced but within one beat, as in Italian. Where syncope is necessary for meter (e.g. in “discoverers,” (…) no elision is inidicated unless an apostrophe appears in the copy text. (The Complete Poetry of John Donne: Edited with an Introduction, Notes and Variants by John T. Shawcross p. xxii)

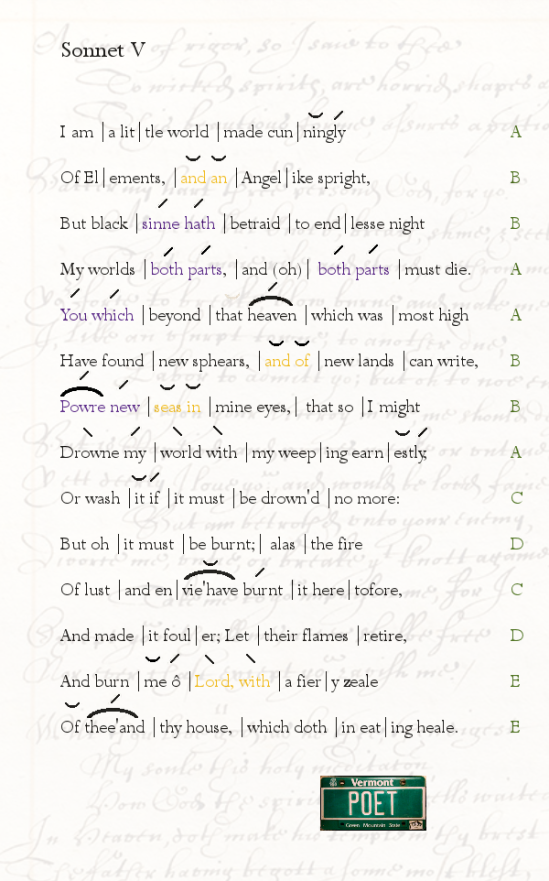

If Donne’s orthographic intentions matter to you, look no further. Without further ado, here is Donne’s Sonnet V as edited by Shawcross:

I am a little world made cunningly

Of Elements, and an Angelike spright,

But black sinne hath betraid to endlesse night

My worlds both parts, and (oh) both parts must die.

You which beyond that heaven which was most high

Have found new sphears, and of new lands can write,

Powre new seas in mine eyes, that so I might

Drowne my world with my weeping earnestly,

Or wash it if it must be drown’d no more:

But oh it must be burnt; alas the fire

Of lust and envie‘have burnt it heretofore,

And made it fouler; Let their flames retire,

And burn me ô Lord, with a fiery zeale

Of thee‘and thy house, which doth in eating heale.

the Scansion (& my high horse)

Back on my post discussing Donne’s Holy Sonnet 14, I covered the same issues that are relevant to this poem. So I’ll try not to repeat too much. As with Sonnet 14, Donne spells ‘er’ words, ‘re’, when he wants you to treat them monosyllabically. He spells power as powre, for example. When he doesn’t want you to pronounce the ‘e’ in ‘ed’ words, he apostrophizes them, e.g. drown’d. Most importantly, when Elizabethan poets wanted you to elide vowels, they used the apostrophe to show you which ones:

envie‘have

thee‘and

These days, by contrast, we write you’ve instead of ‘you‘have’ and I‘ve instead of ‘I‘have’. It’s the same thing. Contractions weren’t normalized and besides that, Donne (like other poets) was willing to take liberties where necessary. In every on-line posting of this sonnet (admittedly not by professional editors) these little niceties are left out. A little more unforgivably, the circumflex above the o (ô) is also left out. If reading the poem the way Donne wrote it matters then, well, it matters. As for sonnets in print (and edited by the experts) all but one leave out the apostrophes between the words above. Goes to show that professionals are just amateurs with degrees.

None of this is really a problem until your instructor gives you this poem as a homework assignment. They probably recommended a book like the Norton “Critical” Edition (air-quotes) or provided a photocopy that entirely omits the original cues that would make scanning the work so much easier. If you had the edition by Shawcross, then you might come up with something like this:

So, the first thing to be said is that once historical concerns are out of the way, scansion isn’t an exact science. Where one person might read a pyrrhic foot, another might read an iamb, spondaic or trochaic foot (depending on the words and phrase). My own practice is not to scan it the way we would read it in the 21rst century, but how Donne might have imagined it or read it himself. With that in mind, I find Donne to be the most metrically inventive and resourceful poet in the English Language (and including Shakespeare) and the most enjoyable to scan. The way Donne plays meter against phrase and line is beautifully flexible and allows for a wide variety of shade and inflection. My own scansion reflects that. I made some choices that others are welcome to disagree with (offer your own). We’ll go by quatrains just to illustrate how important meter can be to a poem’s meaning.

I am a little world made cunningly

Of Elements, and an Angelike spright,

But black |sinne hath| betraid to endlesse night

4. My worlds both parts, and (oh) both parts must die.

Line 1. I love this first line.

Line 2. Angelike is read is angelic.

Line 3. Most modern readers would probably read the second foot as strictly trochaic. The meter, however, makes a spondaic reading possible. I decided to go for it because (according to my rule of thumb) if a foot can be read as an iamb (or more simply if we can emphasize the second syllable) then we probably should (at least to see what effect it has on the line). In this case, emphasizing hath emphasizes the betrayal, sort of like: “Oh no! What have you done?” or “O no! What hast thou wrought?” Remember, Donne was living in the midst of dramatists like Jonson, Shakespeare and Marlowe. One Sir Richard Baker said of Donne that he was “not dissolute, but very neat; a great visiter of Ladies, a great frequenter of Playes, a great writer of conceited Verse.” The playgoing rubbed off on him. The Elizabethan era was dramatic and Donne’s poems are like little speeches — little dramatic set pieces.

You which beyond that heaven which was most high

Have found new sphears, and of new lands can write,

Powre new | seas in mine eyes, that so I might

8. Drowne my | world with my weeping earnestly,

Line 5. Heaven was pronounced as a two syllable or one syllable word by various poets. The reasons seem to have involved dialect or bald poetic expediency. Shakespeare, for instance, seems to have pronounced it disyllabically. Donne, to judge by his poems, may have pronounced it quickly and as a monosyllabic word, heav’n (or at least that’s how he treated the word in his poems).

Line 7. Once again, I opted to emphasize the second syllable. A trochaic first foot would hardly be unheard of in Donne’s day (though used conservatively). I think he would have expected his readers to keep the meter where such a thing is possible. In this case, it makes sense. In Life 6 both instances of “new” are in an unstressed position. In line seven, it makes dramatic sense that Donne would be asking God to make new seas.

Line 8. For the same reasons, I emphasized ‘my’ in the first foot of the eighth line. Donne, in the first line, calls himself a little world. It makes sense, to me, that Donne is emphasizing his world as opposed to God’s e.g. You have your world, and I have my world. Also, this pattern of emphasizing normally unstressed words is a technique that one finds throughout Donne’s poetry. The trick is what makes Donne’s poetry so speech-like and declamatory (he was, after all, famed for his oratories at the pulpit).

Or wash |it if| it must be drown’d no more:

But oh it must be burnt; alas the fire

Of lust and envie‘have burnt it heretofore,

12. And made it fouler; Let their flames retire,

Line 9. Again, rather than read the second foot of this line as pyrrhic, I made it iambic. If one reads Donne the way I do, one can’t help detect a sense of humor. “Alright already,” he seems to say, “if you can’t drown the word again, then wash it. Fine.”

And burn |me ô| Lord, with a fiery zeale

Of thee‘and thy house, which doth in eating heale.

Line 13. If there was any doubt as to Donne’s predilection for shifting stress in ways a modern reader might miss and dismiss, the second foot of this clearly puts that to rest. Here’s how Wikipedia describes the circumflex above ‘o’.

The circumflex has its origins in the polytonic orthography of Ancient Greek, where it marked long vowels that were pronounced with high and then falling pitch. In a similar vein, the circumflex is today used to mark tone contour in the International Phonetic Alphabet.

All educated Elizabethans were schooled in classical Greek and Latin (even if they didn’t remember it all). Donne, with the circumflex  above the expostulation ‘ô’, makes clear that ‘ô’ receives the stress, not ‘Lord’. One can read that ‘ô’ in a variety of ways. I personally read the ‘ô’ with, perhaps, grim humor instead of exhausted despair. Some scholars seem to think Donne lost his sense of humor with his later divine poems. I’m not so sure. A quirky sense of humor runs through almost all of Donne’s poetry. I’m not convinced his old age was as sour or strict as some scholars might have us think.

above the expostulation ‘ô’, makes clear that ‘ô’ receives the stress, not ‘Lord’. One can read that ‘ô’ in a variety of ways. I personally read the ‘ô’ with, perhaps, grim humor instead of exhausted despair. Some scholars seem to think Donne lost his sense of humor with his later divine poems. I’m not so sure. A quirky sense of humor runs through almost all of Donne’s poetry. I’m not convinced his old age was as sour or strict as some scholars might have us think.

Here’s how I read (and hear) it — the humor. It took me about 20 times to get the tone roughly where I wanted it. See what you think. (I’ve had a bad cough, from whooping cough, for about three months now. Can you tell?):

As I’ve written before, a masterfully written metrical poem has two stories to tell – two tales: one in its words; the other in its meter. To me, the meter suggests a touch of wry humor that knocks the academic dust right out of it.

Spank me, ô Lord, for I’have been bad.

Unlike some of Donne’s other sonnets, the meaning, I think, is fairly straightforward. The point of the sonnet, in my opinion, is not to display metaphysical cunning (as in many of his other poems), but to create a mood, much like a small soliloquy. In my reading, I’ve chosen to interpret that mood as wry humor.

So, once again, let’s go quatrain by quatrain:

I am a little world made cunningly

Of Elements, and an Angelike spright,

But black sinne hath betraid to endlesse night

4. My worlds both parts, and (oh) both parts must die.

1. Donne sets the stage by dividing himself into his corporeal body and his incorporeal soul. C.A. Partrides observes that “man was habitually said to be the microcosm or ‘abridgement’ of the universe’. (John Donne The Complete English Poems p. 437)2. The elements (the body) and an angelic sprite (the soul).

3. The overstatement (even for Donne I think) of this line and next partly invite me to read the sonnet with some humor.

4. The assertion that the soul “must die” was unorthodox (C.A. Partrides calls it “a potentially dangerous notion”) and, at the wrong place and time, flirted with heresy. If the sonnet was interpreted as an exercise in wry humor, the assertion probably felt less heretical if it was even an issue.

You which beyond that heaven which was most high

Have found new sphears, and of new lands can write,

Powre new seas in mine eyes, that so I might

8. Drowne my world with my weeping earnestly,

5. You refers to Christ. 7. Powre can be read in the sense of create.

7-8. Donne asks Christ to create oceans out of Donne’s tears so that he may drown himself in his “earnest weeping”.

Or wash it if it must be drown’d no more:

But oh it must be burnt; alas the fire

Of lust and envie‘have burnt it heretofore,

12. And made it fouler; Let their flames retire,

9. “be drown’d no more” This refers to God’s promise after Noah’s flood, symbolized by the rainbow, to never flood the world again. “neither shall there any more be a flood to destroy the earth.” Genesis 9.11

11. heretofore – hitherto

12. “let their flames retire,” That is, let the fires of lust and envy retreat. Lust presumably refers to his youth and envy to Donne’s involvement on Church and Court politics. Lust and envy are among the seven deadly sins.

And burn me ô Lord, with a fiery zeale

Of thee‘and thy house, which doth in eating heale.

14. The last line is a reference to Psalm 69.9. “For the zeal of thine house hath eaten me up… When I wept, and chastened my soul with fasting, that was to my reproach.” Shawcross, in his notes to this sonnet, also sees a reference to the Eucharist. The blood and body of Christ constitutes his house and the eating of the wafer, Christ’s body, removes the sin of partaker. The final image is a compelling one. The image is that of God burning away (consuming), in a fiery conflagration, at least one part of Donne’s world — the part composed of the “Elements”. What will remain, presumably, is the Angelike spright. However, this interpretation threatens to contradict Donne’s earlier assertion that both parts of his house must die. The question then pertains to what, exactly, will remain once God is done ‘consuming’ Donne with his purifying conflagration. What, exactly, will be “healed”? It’s a riddle unless we treat Donne’s first utterance as wry overstatement, and Donne’s conclusion as an implied admission that his soul is eternal and cannot be destroyed, only purified or healed.

And that’s that. I hope you enjoyed the post. Let me know. (Guess I’m making up for lost time.)