“When I state myself, as the representative of the verse, it does not mean me, but a supposed person.”

“Death—so—the Hyphen of the Sea—” 1454

Do People moulder equally,

They bury, in the Grave?

I do believe a species

As positively live

As I, who testify it

Deny that I—am dead—

And fill my Lungs, for Witness—

From Tanks—above my Head—

I say to you, said Jesus—

That there be standing here—

A Sort, that shall not taste of Death—

If Jesus was sincere—

I need no further Argue—

That statement of the Lord

Is not a controvertible—

He told me, Death was dead—

FR391/J432

I included the quotes above because the first is Dickinson stating that she adopts personas in her poetry. The word “persona” was first used in the 17th century, but may or may not have been one Dickinson was familiar with. The second because Dickinson, in many, many of her poems, treats the sea as a kind of burial ground in and of itself. A great article at the Dickinson Electronic Archives examines just this propensity later in her career, writing:

Dickinson began writing poems that referred to the sea, and particularly to the experience or threat of drowning, with increasing frequency.

One of the poems, given as an example, begins: “Drowning is not so pitiful/As the attempt to rise.” Yothers, the author of the article, cites another poem, writing that “this capacity of the sea to engulf the human body and brain appears in another poem from 1863, Fr. 631A (MS H 90). The poem includes the lines: ““The River reaches to my Mouth – / Remember – when the Sea / Swept by my searching eyes – the last – / Themselves were quick – with Thee!”

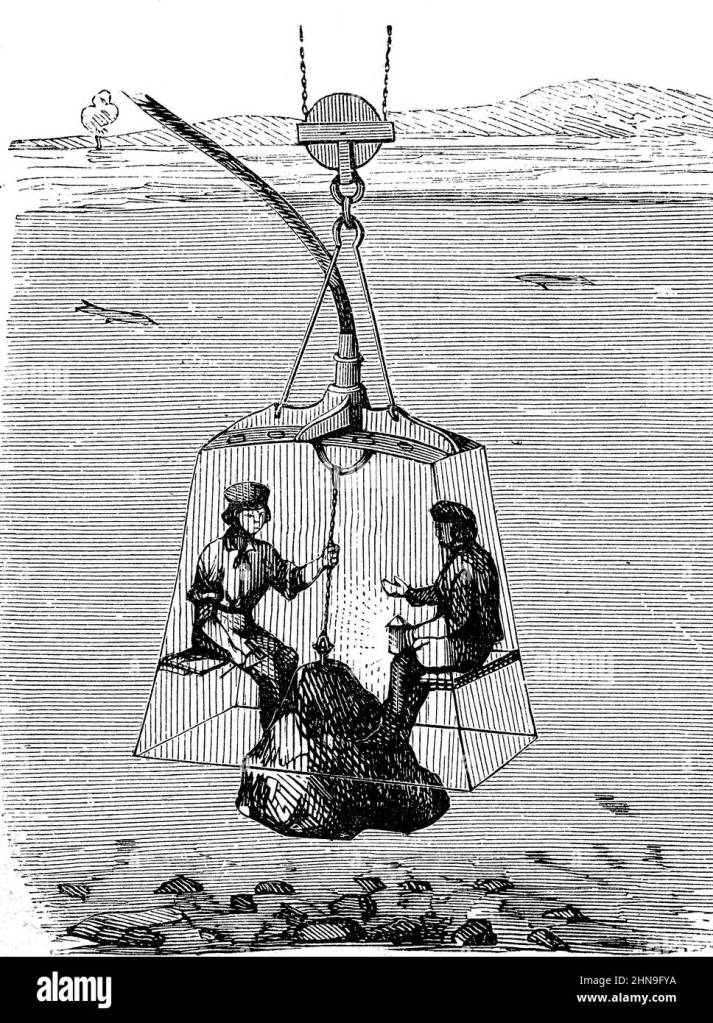

The point is that like the earth’s surface, the sea’s surface is another division—a metaphorical and symbolic boundary—between living (above) and death (below). But undermining this nice metaphor is the diving bell and the diving suit, which Dickinson—given her love and knowledge of science and her frequent references to sailing and the sea—would certainly have been aware of. She took it as an opportunity to wryly undermine Christian theology. She starts by asking if people moulder differently:

Do People moulder equally,

They bury, in the Grave?

I do believe a species

As positively live

The initial question mischievously undermines the temptation to read this poem in the manner that some readers do. To wit, the question she asks isn’t: Do some live and some die in the Grave? No. Implicit in the question is that everyone moulders. Period. Do they moulder/rot unequally? Maybe. Possibly. But who cares? They’re dead. They’re mouldering. So there’s that. But then she goes on to say that there’s a “species” who live, but we won’t find them in the Grave, because she’s already eliminated that possibility through her mischievous rhetorical question. A “species” does live.

As I, who testify it

Deny that I—am dead—

And fill my Lungs, for Witness—

From Tanks—above my Head—

The temptation, including my own, is to treat a passage like this (as in so many of her poems) figuratively—as metaphor or metonymy. For example, does she really mean lungs? What does she mean by Tanks? What does she really mean by above my Head? And yet the quatrain is written with a straightforwardness that clearly describes a diving bell or suit. I see two possibilities. If one wants to read this figuratively, which is possible given Dickinson’s poetics, then the Lungs could be her poetry. Spoken poetry, after all, requires that the lungs be filled. The Tanks could be inspiration or even divine inspiration.

In short, Dickinson could be stating that she lives on in her poetry (a hoary old conceit, just ask Spenser and Shakespeare). Her poetry “testifies” to the denial of death. She writes, “[I] fill my lungs—[behold! or “for Witness” or look at the Tanks]—from Tanks—above my Head—” The Tanks could also mean you, the reader, though this strikes me as pushing the conceit to its limits and beyond. That said, we are, literally, above her Head (Dickinson, being buried). The second way to read this quatrain is to treat Dickinson as assuming a persona (that of the diver) and that she is straightforwardly describing a diving bell or suit. She is speaking to us as a diver who, in the next two quatrains, will use their living burial to troll scripture.

I say to you, said Jesus—

That there be standing here—

A Sort, that shall not taste of Death—

If Jesus was sincere—

Except that’s not quite what Jesus said. According to the King James translators, he said: “Verily I say unto you, There be some standing here, which shall not taste of death, till they see the Son of man coming in his kingdom.” She could have written: “Some be that shall not taste of Death…” That would have kept the meter. Instead, one can read—”A Sort“—as Dickinson’s sly riposte. Remember that the poem’s opening lines flatly deny that there’s anything other than mouldering in the Grave. Option A is mouldering. Option B is mouldering. There is “a “buried Sort”, however, who don’t moulder. And they are buried at Sea. Viola!

I need no further Argue—

That statement of the Lord

Is not a controvertible—

He told me, Death was dead—

Dickinson no longer needs to Argue with the true believers. She’s persuaded. Behold! For Witness! The statement of the Lord truly is incontrovertible. Here I stand, in my diving bell, buried and living where centuries and centuries of men lie dead and mouldering.

For witness what science and engineering have wrought!

The entirety of the poem, read this way, is Dickinson trolling Christian faith. You can almost see her in her diving suit, shrugging: See? Just like he said: Death is dead! The joke is that it isn’t faith but science and engineering that have defeated death, utterly undermining the scripture’s intent. On these terms, in other words, Dickinson will accept Jesus’s words as incontrovertible—but not on faith. (I do think there’s a lot of laughter in Dickinson’s poetry, and possibly more so than any of her 19th century peers.)

Nonetheless, one can also read the conceit as metaphor—ourselves as the “tanks” that give air and lungs to her poetry. But read this way, the deadpan “He told me, Death was dead—” loses its punch and humor. If Dickinson is declaring that she will live on in her poetry, then one wants to read the last line earnestly and devoutly. I have a hard time reading it that way (and the conceit would strike me as uncharacteristically ham-handed). Its colloquial directness suggests a dead-pan delivery. My instinct is to read Dickinson as assuming a persona (as she told Higginson she was wont to do) in order to impishly troll Christian doctrine (“I do not respect doctrines,” she once wrote a Mrs. Joseph Haven to explain her non-attendance at a church service [p. 8 Emily Dickinson’s Poetry, Weisbuch].) It’s as if someone said to her: If you don’t accept Jesus Christ as your Lord and Savior then there will be no afterlife for you. To which she said: Hold my beer.