This is one of my favorite Sonnets by Shakespeare. And it is the one sonnet, of the 154, that some Shakespeare “scholars” consider to be apocryphal – which is to say, they think it isn’t by Shakespeare. I, drawing my line in the Vermont snow, say they are wrong. This sonnet, unless some letters are discovered, is as close as we may come to hearing Shakespeare’s unscripted voice.

Those lips that Love’s own hand did make

Those lips that Love’s own hand did make

Breathed forth the sound that said ‘I hate’

To me that languish’d for her sake;

But when she saw my woeful state,

Straight in her heart did mercy come,

Chiding that tongue that ever sweet

Was used in giving gentle doom,

And taught it thus anew to greet:

‘I hate’ she alter’d with an end,

That follow’d it as gentle day

Doth follow night, who like a fiend

From heaven to hell is flown away;

‘I hate’ from hate away she threw,

And saved my life, saying ‘not you.’

The figurative language is straightforward – the simplest of his sonnets. (Figurative language is any that uses metaphor, simile or any of the other rhetorical figures.) But what is most unique is it’s meter: Iambic Tetramater – the only one of Shakespeare’s sonnets not written in Iambic Pentameter. Some scholars say it must have been an early sonnet, which is possible. The supposition, I suppose, is that Iambic Tetrameter is a warm up to Iambic Pentameter or that a more youthful poem will be less figurative. These are all possibilities, but the humor and ease of the sonnet feels more assured to me. It’s a friendly joke. I like to imagine that it was written after a marital spat as a kind of humorous peace offering. In that respect, I like to think it’s the most personal of Shakespeare’s verses and offers a little glimpse into his home life and the kind of temperament he possessed.

One other note: This is among the first sonnets that I read by Shakespeare (when in highschool) and it was the first that I immediately understood. For me, it opened the door to all his other sonnets and made Shakespeare human.

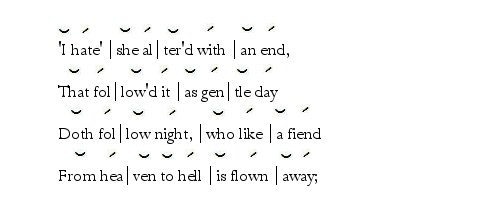

The scansion of the sonnet is fairly straightforward, but I’ll go with the assumption that some readers are coming to this for the first time. The first four lines would be scanned as follows:

These lines are all solidly iambic and there is nothing figurative in any of them – I’m willing to assert that in no other Sonnet by Shakespeare are there four consecutive lines of unadorned English.

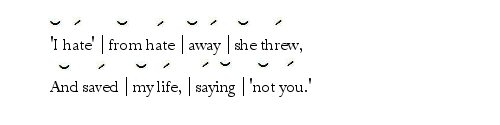

Shakespeare mixes it up a little. The first feet of the quatrain’s first two lines are trochaic (a Shakespearean sonnet is divided into three quatrains – each four lines – and a final couplet). What’s more interesting is Shakespeare’s use of personification – a Shakespearean specialty found throughout his sonnets and plays. He personifies the heart and tongue as though they were dramatic characters – the single most telling aspect, to me, that favors Shakespeare’s authorship. Mercy, like one of the virtues in an older miracle play, comes to his lover’s heart and the heart chides the tongue: be more sweet to your poor William!

The final quatrain is all very straightward in terms of its poetic language. It offers the entirely straightfoward and ordinary observation that the “day doth follow night”, then follows that with a sort of simile or analogy comparing the night to “a fiend (From heaven to hell” flown away). The image is all but hackneyed, even in Shakespeare’s day, but it’s hackneyed in an easy-going sort of way.

(Notice that I’ve scanned the last line of the quatrain so that the second foot reads as an anapest. One could read the line as follows:

With this scansion, the iambic rhythm is maintained – heaven reads more like heav’n. I know this reading gives some metrists heartburn, but that’s the way poets write. Heaven is one those words that Shakespeare might have treated as a compromise between an iambic foot and an anapest.)

This isn’t a virtuosic show-piece and it’s clearly not meant to be. I get the feeling that he jotted this quickly, unselfconsciously for his own pleasure and the pleasure of his lover. And who was she? The final couplet, interestingly, may hold a clue.

Notice the trochaic foot in the final line before the iamb ‘not you’. I can’t help but think this little metrical jest is deliberate. He could have written “she said ‘not you‘”, retaining the “proper” iambic rhythm, but instead deliberately employed the trochaic foot, adding emphasis to ‘not you‘! Shakespeare breaths a sigh of relief.

The contorted syntax and grammar of the second to last line is ‘a little’ unusual for Shakespeare. In Shakespeare’s day people didn’t talk this way. It could be for the rhyme but this idea strikes me as overly awkward even for a young Shakespeare – the greatest literary genius of our language. He was more resourceful than that. Something is up.

There is speculation, and I agree with the speculation, that Shakespeare was emplying a pun. ‘I hate’ from hate away‘ could be read as ‘I hate’ from Hathaway ‘ or, to spell it out, ‘I hate from Anne Hathaway.’

And in case you don’t already know it, Anne Hathaway was Shakespeare’s wife.

If you enjoyed this and are looking for more information on meter, check out my Guides to Meter and another analysis of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 116, Shakespeare’s Sonnet 129, Spenser’s Sonnet 75 and Milton’s Sonnet: When I consider….

Thank you very much. I was looking for a Iambic Tetrameter for my music students, to see the opening of Haydn op. 1/1 with a different perspective. I am looking forward to see more of your website.

Best, and Thank you again, Rainer Schmidt

LikeLike

Thanks Rainer. Your comment prompted me to go listen to the little divertimenti. :-)

LikeLike

Pingback: Dama recatada, senhora pudica, amada esquiva – Andrew Marvell em tradução | escamandro

This helped me so much! I love Shakespeare and I’m doing my own poetry analysis for a poetry portfolio and I chose this sonnet. I had no clue where to start. So this helped a lot! Thanks!

LikeLike

Wonderful! I have just written a sonnet in iambic tetrameter, and was looking for a precedent to justify my experimentation. Thank you!

LikeLike

I am an undergraduate studying in England at the University of Leeds and am working on a close reading of a poem for an assignment. This has been really helpful for thinking about meter!

LikeLike

Hi Charlotte, thanks for the comment. :) I’m going to google Leeds and see what there is to see.

LikeLike

You and the whole world completely misunderstood this poem, which is a symbol, in the sense that it has only one meaning.

LikeLike

Congratulations on starting your new blog. And yes, you can use my comment section as a link to your new blog. I see that you’re dedicated to proving that the Earl of Oxford was the real Shakespeare. Unfortunately, that theory recently took a knife through the heart.

https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2017/jan/08/sherlock-holmes-of-the-library-cracks-shakespeare-identity

Even Shakespeare’s contemporaries identified Shakespeare Gent. as Shakespeare the Playwright. That Oxfordian dog just don’t hunt no more. If you want to debate this latest discovery, do so at your own blog. Not mine. I’ll delete your comments. I have as much interest in debating Shakespeare’s identity as debating the rotundity o’th’earth.

LikeLike

I used Sonnet 145 for the lyrics in the one song I wrote and recorded that didn’t yet have a theme. The composition was in 4/4 time, and I had no lyrics. What to do? After a few glasses of Scotch, I got the brilliant idea to ransack Shakespeare, specifically his sonnets. Surely there was something there I could steal. But alas, all of them were written in iambic pentameter — not the stuff of pop tunes — except this one aberration, No. 145. It was written not in pentameter but in octameter! Pop meter! I applied it to great success (in my mind.) It’s here on Spotify if you’d like to listen:

LikeLike

Ha! I didn’t want to respond until I could listen to your track. That must have been some hell of a Scotch. I know what you mean by great success in ones mind. My successes are legion. :)

LikeLike

It’s a total and utter misunderstanding of sonnet 145. No wonder, though.

LikeLike

Let me guess, you’re still shilling for the Earl of Oxford? Whose magnificent fart before Queen Elizabeth sent him into self-exile? The aristocrat who inconveniently died years before Shakespeare wrote his last play?

LikeLike