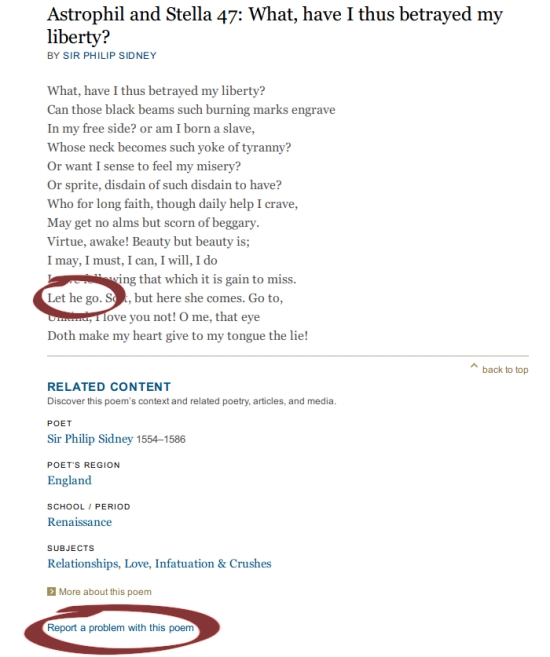

So, while I was writing the post immediately preceding this one, Sidney’s Sonnet 47, I visited the Poetry Foundation to see what information they had on the poem and a reliable text. Here’s what you will find (as of today, October 10th 2014):

So, there are all kinds of problems with this poem, but the most egregious is the typo. That’s okay. There are all kinds of typos in my own posts; although if someone were nice enough to bequeath $200,000,000 to me, I might hire — oh, I don’t know — an “archive editor” to correct my mistakes? So, I thought I’d “report a problem”:

Problem description: The mistakes: "Though" should read "tho'" "Let he go" should read "Let her go" Also, according to the best resource I've got, there are no exclamation points in the original poem. The poem should read: What, have I thus betrayed my liberty? Can those black beams such burning marks engrave In my free side? or am I born a slave, Whose neck becomes such yoke of tyranny? Or want I sense to feel my misery? Or sprite, disdain of such disdain to have? Who for long faith, tho' daily help I crave, May get no alms but scorn of beggary. Virtue awake, Beauty but beauty is, I may, I must, I can, I will, I do Leave following that which it is gain to miss. Let her go. Soft, but here she comes. Go to, Unkind, I love you not: O me, that eye Doth make my heart give to my tongue the lie.

The response:

Dear Patrick Gillespie, The differences in punctuation between our version and the one you found is the result of centuries of various editors silently altering such aspects. Our version is correct against our copy text. Sincerely, James Sitar Archive Editor The Poetry Foundation

Seriously? And that would include the typo? Does it get any more incompetent or bureaucratic? So, the text of the poem is obviously wrong, but by God if that’s what “the copy text” says, then that’s what goes to print.

As to punctuation, the “one I found” is based on Richard Dutton’s edition which is, itself, based on the 1598 Folio of Sidney’s Works. But what matter? I mean, how can Mary, the Countess of Pembroke, Sidney’s sister (and editor of the Folio edition), compare to “centuries of various editors silently altering” Sindey’s original? Obviously, the Poetry Foundation’s loyalty is to all those “altering” editors (centuries of) rather than to the Sidneys. And there you have it. That’s what a $200,000,000 endowment gets you. The take away? Don’t go to the Poetry Foundation if you want a reliable text.

Hey, Patrick, I just love the the ring of a bright October Friday morning outburst of well-grounded righteous indingnation (heh heh)! ;-)

LikeLike

You know, it got under my skin. The guy doesn’t even say thanks, but no thanks, right? I mean, I wanted to put him in quotes and write:

“…our version is correct against our copy text,” he sniffed.

How can you call yourself an “archive editor”? I don’t get it. At least correct the typo. Sheesh!

LikeLike

Sheesh! One of the typos was deliberate, the other a pesky accident. So it goes!

LikeLike

I’d trust them more at the Poetry Foundation had they been endowed a minimum wage.

LikeLike

The response sounds like a stock email they send out to all such complaints about old poems so they don’t even have to read/check anything, which would explain why they didn’t even mention/correct the typo. I doubt seriously that any of that grant money went to working on their website’s text archive; they need it to give monetary prizes to mediocre poets that don’t want to get regular jobs (who could learn a thing or two from Wallace Stevens; walk to work everyday, compose poems in your head on the way).

LikeLike

Yeah, you’re probably right. But then why invite readers to send corrections? But, there you have it.

LikeLike

Hey, Patrick, please quit butting into Poetry Foundation business. After all, they are the authority aren’t they?

LikeLike

Ha! They can buy my silence. I hear they’re loaded and I’m always for sale — if paid enough.

LikeLike

Why do they ask you to report a problem if they’re not going to do anything about it? Blame for the typo can be laid at the Poetry Foundation’s feet. Incidentally, exclamation marks, standins for emotion, are a needless and overused grammatical invention. I’m curious to know when they came into fashion–certainly later than Sidney’s time, given the increasingly current penchant for shortcuts.

LikeLike

Yeah, I know. I’m baffled. I mean, I guess if they want to go with whatever’s the latest editorial revision, that’s somewhat open to debate, but the typo!?!

LikeLike

A little off topic, but if someone has read a single great, ageless poem written in the last 60 years that was first published by the Poetry Foundation, please let me know.

LikeLike

I have their poetry anthology: “The POETRY Anthology, 1912-2002” Soon as I got your question, I checked it out, starting at 1950.

Everyone’s going to have a different standard as to what constitutes a “single, great, ageless poem”. My own is this: If I can walk into a room of 50, let’s say, and read a poem that’s met with instant recognition by at least half of them, then the poem’s probably great and ageless (or on its way). I don’t give a rat’s rear-end what any single critic or poet thinks. Back when I wrote the post “Let Poetry Die“, I wrote that in any given crowed, most probably couldn’t name a single poem by a single poet since the modernists. Afterward I read on a separate website that a journalist, while in the newsroom, tested her fellow journalists and discovered the same — a roomful of journalist couldn’t come up with a single line of poetry since the modernists and even had a hard time thinking up poets.

So, by that standard, I’d have to say that there probably wasn’t a single poem (published by Poetry) that an entire stadium-full of ordinary readers could guess or name. How much of that is Poetry’s fault (the publication) or the fault of the utterly forgettable (and already forgotten) generations that followed the modernists is open to debate. They published “The Love Song of J. Alfred Profrock, but that was when giants walked the earth. With less than a handful of exceptions, the last 60-70 years of poetry have been really awful — but all arts go through their phases: music, art architecture, etc…

LikeLike

I’ve only been reading Poetry Magazine since ca. 2010, but within that time I vividly recall only one poem that I read over and over thinking that it deserved to be a future classic: Steve Gehrke’s The New Self.

By pretty much any reasonable standard (ie, probably not Patrick’s ;) ), Ashbery’s Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror is a classic, and will be studied/read by future generations if only because of its profound influence on the poetry after it and its embodiment of so many postmodern ideals. Personally, I’m a huge fan of James Merrill (I feel he was only second to Yeats in terms of great 20th century poets), and many of his were originally published in Poetry: A Tenancy, McKane’s Falls, From the Cupola, et al.

Let me say, though, that it’s really hard to discuss “greatness” and “agelessness” when it comes to ANY contemporary art, because one can only take an educated guess as to the what works/artists will influence future artists, which will be studied in universities, what will be embraced by more general audiences. Poetry moves particularly slowly on this front as we tend not to really appreciate a poet’s achievements until near the end of their life (sometimes only after that).

However, I’ve always said that only fools dismiss all contemporary (or recent) art, since history has consistently shown that most every generation produces classics, even if just a few. In fact, would we think of a poet like Keats as “great” and “timeless” were it not for him being a staple of anthologies and universities for about a century and a half? We can’t overlook the role that critics and academics play in embedding such artists in the general consciousness. So, whatever my complaints with contemporary poetry, I read a lot of it, and Poetry Magazine is not the only game in town. American Poetry Review introduced me to the superb Tomas Transtromer, while I find Rattle more accessible/memorable, and New England Review more consistently excellent. Even smaller publications, like Tar River Poetry, seem to be more consistent; perhaps because they only publish quarterly.

LikeLike

I grant that every generation produces classics. They’re precisely why anthologies were invented. There are transitional cycles in art and there usually seems to be a confluence between the appearance of greatness and the development/perfection of a given aesthetic — in music: the Renaissance, the high baroque, the classical period, the romantics. No one listens much to the music of the early baroque, the Galant, Rococco, Viennese, late classical and proto-romantic — and yet these were all entire generations. Probably only a handful of readers who read this blog could name composers from any of these periods.

In poetry, development occurs over a much longer period of time. In the middle English period, there was a flowering of genius with Chaucer and Gower (the equivalent of the Renaissance in music perhaps), but their innovations were entirely forgotten not more than 50 years after their deaths. Who reads or can name poetry or poets between the 12th century and the 16th? It was a lonely place. A confluence of society, culture and language produced the Elizabethans. The timing was just right (as it was for Chaucer). There was a flowering of geniuses who were all, in their way, equal to the opportunities their period presented — Shakespeare above all. After that free-for-all, society and culture became much more conservative and reactionary. Who reads the poems of Pope or the plays of Congreve or Dryden? College students who’ve been assigned them. Their accomplishments stand above those of their peers but pale in comparison to the Elizabethans. The Restoration, like the Roccocco, is much honored in the breech. After the Elizabethans and up to the Romantics, about two hundreds years, there ain’t much. There’s Milton (who rejected the starched couplets of the Restoration) and Blake — but, in reality, who reads Blake’s longer works? Not me — like cough medicine, that stuff. But what a wonderful anthology those 200 years make!

After the Romantics came the modernists. After the modernists? Another era for the anthologist. (William Logan likes James Merrill.) Out of curiosity, and apropos to this conversation, I checked out Merrill’s Collected Poems at Amazon. There’s a review there, 4 stars, that’s worthy of Logan, but better — the kind that damns with praise. The reviewer describes Merrill’s legacy better than I ever will:

“…somehow they reminded me of the good chairs in my mom’s living room–you could admire them, but you couldn’t sit down.”

Perfect. That’s an analogy to be proud of; and really describes the effect Merrill’s poetry has on me (along with Logan’s poetry — and it’s no coincidence Logan admires them). As to Ashbery, “profound influence” doesn’t mean much. Not saying that Asbery’s poem won’t or shouldn’t be anthologized. No, Ashbery’s poem is precisely the kind of poem we want to anthologize — it was “influential”. Students should be assigned the poem and should be made to analyze it. (That’ll kill it.) Anthologies are where influential poems go (and to die sometimes).

We live in an era of the anthology.

I agree with your estimation of the lesser known publications.

LikeLike

It is possible that given demographic changes, not to mention the growing schism between the “academy” vs. proles, poetry like most media in this digital age will “go silo” and nothing will ever be universally great again. Some silos (The Poetry Foundation) will have endowments and money and some (administered between drywall contracts) will have more revolutionary poets and readers. If there is continental consensus about anything, it will be as to the sanctity of Free Speech, bandwidth and the WWW. Vermont might ultimately secede from the Union but by the same token Robert Frost would remain a great poet.

LikeLike

There will be great poets again. I don’t for second think there won’t be (and they may be among us now). Maybe history will decide that I was one of them? Who knows…

There’s a good passage Charles Rosen’s book “The Classical Style” that nicely sums up my own thoughts on the matter:

“The sonatas and symphonies of Schumann are constantly embarrassed by the example of Beethoven: their splendor breaks through his influence, but never starts from it. All that is most interesting in the next generation is a reaction against Beethoven, or an attempt to ignore him, a turning away into new directions: all that is weakest submits to his power and pays him the emptiest and most sincere of homages.” p. 379

Modernism is to the 20th (and now 21rst) century what Beethoven was to the Romantics. I can only think of a small handful of poets who have attempted to ignore or turn away from the modernists. They all, the poets of the ast century, submit to their power and pay them their emptiest and most sincere respects. Ashbery is nearly always embarrassed by the example of Wallace Stevens (by far and away the better poet). The splendor of Ashbery’s poetry sometimes breaks through his influence.

LikeLike

That Rosen quote is absurd for several reasons:

1. However much Schumann, Brahms, and Mendelssohn were indebted to Beethoven, they were not, in any way, inferior to those that reacted against him. Wagner is perhaps the one exception, but his “reaction” was a bit easier given that Beethoven didn’t leave a legacy of great opera (and, even then, you’d have to break my arm to get me to decide between Wagner, Brahms, and Schumann).

2. Very few genuinely “reacted against” Beethoven. Beethoven himself “reacted against” classicism, and, to a large extent, Mendelssohn and Brahms “reacted against” Beethoven as much by going back to a high form of classicism, while those like Wagner, Liszt, Berlioz, et al. were following up on Beethoven’s more romantic inclinations, especially in terms of program music (in that respect, Beethoven’s 6th symphony proved more revolutionary than any other).

3. Even a revolutionary like John Cage has discussed the influence of people like Brahms–the arch-classicist of romanticism–on modern music. In many ways, the romanticism that was most influential to modern music weren’t revolutionaries, but the “conservatives.” Wagner and Liszt sound far more a product of their time.

As to your poetry comparison, I think that’s more fair, but, then again, it’s hard to pinpoint the exact influence of modernism beyond the dominance of free-verse. The “remix” nature of The Waste Land and The Cantos have been somewhat influential, but not exactly dominant. It’s equally hard to pinpoint the nature of Stevens’s influence, as nobody since has really developed their own elaborate symbolic system (really, Stevens may be the first since Blake did it). That leaves Yeats, whose influence is primarily amongst the formalists. Given all that, I’m not sure exactly how any post-modernists CAN completely “ignore” (or just wallow in) that influence since it’s really heterogeneous.

Really, if I was going to choose the genuine dominant ideology of the late 20th century it would be the confessionalists. There was poetry that DID make a pretty clean break from modernism and whose influence is still felt. Maybe we should be looking more at Plath and Lowell?

LikeLike

I wouldn’t base too much of your outrage on that one quote from an entire book. You might want to first understand exactly what Rosen means by “turning away into new directions”. Secondly, Rosen explains quite concisely why Beethoven did not, in fact, “react against classicism”. As he aged, he did just the opposite in fact; but in order to understand what Rosen means you have to think of Classicism in a different sense (or, better, in the sense for which the term was intended — the structural component rather than its “sound”). Beethoven’s late pieces are far more classical than his earlier pieces (which may strike you as utterly counter-intuitive). His earlier pieces have much more in common with the late classicists like Hummel. But that’s all I’m going to say on that. You should consider reading his book. Likewise, what characterizes Yeats goes beyond his formalism. I’ve read some convincing criticism that finds Yeats’ influence far-flung and far afield.

Your point as regards the confessional meme is well-taken; but I was thinking of modernism’s influence in terms of form and structure rather than content (to be as vague as possible). It also extends to content, of course.

LikeLike

[[[No one listens much to the music of the early baroque, the Galant, Rococco, Viennese, late classical and proto-romantic — and yet these were all entire generations. Probably only a handful of readers who read this blog could name composers from any of these periods.]]]

One thing to keep in mind is the continuum of any artistic evolution; there is rarely a clean split between between periods, where everything before is one thing and everything after is another. To take your musical example, is Monteverdi late Rennaissance or early Baroque? Likewise, both Mozart and Beethoven have to encompass both the late classical and proto-romantics, however you mark that divide.

Anyway, I think there is a better explanation that you’ve overlooked for why so few today know post-modern poetry, and it has little to do with either the quality of that poetry or publications like Poetry: namely, it’s the explosion of new artistic forms and media within the 20th Century: Film, TV, video games, comic books, the internet, recorded music, etc. There is just so much more out there that’s demanding of the masses’ attention, it’s not surprising that they turned away from older artistic forms; it’s not as if painters and novelists (with very few exceptions) have been exceedingly popular in that same time frame, and the ones that are are almost universally loathed by enthusiasts (Steven King, Thomas Kinkaid).

The popularity of poetry amongst the masses in the 19th Century was likewise an unusual confluence of factors ranging from elevated literacy levels, to the Industrial printing press and affordable books, and literature just not having any everyday rivals for the arts (music and painting, of course, still required people to go out and experience them). Especially amongst the middle class, literature was almost unrivaled as a form of accessible, mass entertainment. The 20th century changed this by making several new forms that were equally accessible.

One of the biggest problem with the notion of anthologies is that, along with the explosion of media and art-forms has also come the explosion of various institutions, standards, voices, ideals, etc., so the notion of producing a single anthology that encompasses them all is next to impossible, because “old straight white men” are no longer the only opinions that matter. This is why we’ve seen anthologies for black poetry or women’s poetry or gay/bi-sexual poetry. I don’t think it’s possible to produce any “universal” anthology any more, and with that impossibility comes a much grayer area about what poets/poems should be preserved and passed on, and how they should be. Our awareness of alternate traditions is ever growing.

On a side note, I have read Pope, Dryden, and Blake’s long works without being assigned them: shame you think of the latter as cough medicine! They’re the finest visionary poetry ever written outside of Milton and Dante. I simply disagree with that Merrill review, however much of a nice metaphor that might be. Merrill’s poetry is undoubtedly finely crafted like those good chairs, but I can think of few post-modern poets I consider great that were also more warm, welcoming, and accessible. Some of his very early work is a bit too chilly, but a very Auden-esque casualness dominates his late voice far more than it does most every major 20th century poet (certainly more than Eliot, Stevens, and Yeats). There’s certainly nothing “hands off” with poems like Days of ’64 or An Urban Convalescence or The Broken Home or Verse for Urania.

LikeLike

Your reasoning, as to why so few know or read post-modern poetry might be sound if it didn’t fail to explain why so many of these same contemporary readers are intimately familiar with modernist poets (and older). If modern media were the pernicious influence you make of it, one would expect that *all* poetry, and not just post-modernists would suffer; but that’s not what we see. Modern media certainly plays its part, but it’s not the bête-noir and escape clause that modern poets would like it to be.

LikeLike

“On a side note, I have read Pope, Dryden, and Blake’s long works without being assigned them…”

Yes. I read them too and also listen to CPE Bach, WF Bach and Micheal Haydn. And good luck trying to find their music or the poems of Dryden or Pope at your average bookstore. I don’t say that to be a snob. There are others who cultivate extremely hard to find 70’s bands or Jazz artists or early gospel. We’re not rare, but we’re definitely birds of different feather. :-)

LikeLike

Correction: I meant Schoenberg talked of Brahms’s modernism, not Cage.

LikeLike

Jonathan and Patrick, your thrusts and parries have taken my breath away. I once placed 99 percentile in humanities on a teachers’ exam yet feel I would need not only eight more years of college but an extra standard deviation of IQ to keep up with you. I would love to read what you consider your best poem. Could you post it here?

LikeLike

My best poem is probably this one: https://poemshape.wordpress.com/2009/02/28/erlkonigin/

LikeLike

Thanks for the kind words, Cliff. It may interest you to know I’m an autodidact that dropped out of school at 16. I plead to Grant Allen: “I never let schooling interfere with my education.”

FWIW, I make absolutely NO claims to being a great, or even decent, poet. Fact is, too much of my life is taken up with my work (online poker) and my other passions (reading, music, and film) that I don’t get to work at poetry as much as I should to be genuinely good. I will post one of the few of mine that I rather like (my actual favorite is too long to post here), and I trust that Patrick will delete it within a few days (just to prevent any outside copying).

Ode: Being in Reflection

Am I the being I observe to be?

Or is this image not a being true,

But being as imagined, seen not felt.

Such long hours spent inside that what’s outside

Becomes a stranger in a cell of glass.

A cell of cells? What moves the lips that mist

The glass, a mist that clouds a face the way

A thought might cloud the mind, a clouded string

That pulls the puppets dancing on a mass

Of matter? What’s the matter? Substance duels

With property for what’s the proper dual

Ideal. The former, says Descartes, is mind

And matter, (we’ll forget the third that’s God)

Where mind is matter of another kind;

The latter, Chalmers says, assumes that mind

Is matter like all others, but our con-

science is a property that’s all its own.

Dennett, and other damned materialists,

Say conscience is what matter is inside,

That I am all that matter(s) makes me matter(s).

Imagine, if you will, a satin glove,

Identical inside and out, and yet

To see the glove outside is not to feel

It from inside, and, yet again, to feel

It from inside and see it at the same

Moment, the clash of one sense and another,

Is not to say the outside and inside

Are different things entirely or in part.

So which am I? Right now I think (therefore

I think) I need to lose some weight; such long

Hours spent inside (damned southern summer heat)

Means fast food packs on pounds that matter when

I bend to tie my shoes. Ideas, says Plato,

Are what’s eternal, but eternity

Is much too long when turning into Play-Doh.

I raise my tee-shirt sleeve to wipe the mist

Off of the mirror. Everything is clear.

I notice on my sleeve a dangling string;

I wonder what will happen if I pull?

LikeLike

You know, that’s not bad, Jonathan. :-) Though it’s not the kind of poem I would write, it’s true to itself and well-rendered. I can see why you would like Steve Gehrke’s The New Self. You’ll have to let me know when you want to remove the poem.

LikeLike

Jonathan, a damn good poem. A genre of its own. “Philosophical impressionism”???

This is not my best but the quickest I could dig up. Keats, Dickinson and Stevens, btw, are my favorite poets.

April warms the cold

Blood of cold blooded

Things to love or strike

It asks:

What is your venom?

Man makes a list:

Words

Sperm

Words

Sperm

Words

Sperm

Ad infinitum

The answer is history.

LikeLike

The length and manner reminds me of A.R. Ammons. That may be a superficial impression though. There’s a bit too much repetition for my tastes. You should try haiku. That’s a deceptively devilish art form; but you might find your home there.

LikeLike

Thanks for the kudos, Cliff. I can definitely see the Stevens influence in your piece. My only suggestion is that the “words / sperm” repetition isn’t necessary, and would probably be better emphasized with a stanza break.

LikeLike

Thanks, Patrick. It’s not the type of poem I normally write, either, but I was reading a lot of philosophy of mind around that time (can ya tell?) and it just came out. Definitely some influence from Gehrke’s poem (as well as Stevens with the tercet form).

You can go ahead and delete it since both you and Cliff have read it. :)

BTW, I’d read Erlkonigin years ago when I first came here. It is a very, very fine piece with a definite Frostian vibe to it. Did you ever get it published anywhere?

LikeLike

Yes, I could see the theories of mind going on in yours, Jonathan. But nothing out of my repertoire, and I am not haunted that you will speculate yourself into oblivion (despite the “I’s”) in the manner of many confessional poets. A la Stevens, your philosophical scaffolding seems to give you more control of your imagination than I feel in their poetry, although you might could be more implicit about it. By contrast, I get the sense that Patrick eschews philosophy for spontaneous feeling, but nevertheless the material is still organized—organized by technique, as it were, or meter, and the example of Robert Frost. It also helps that Patrick’s spontaneous content is naturally endearing though I would say neither of you is as visual as your model poets. I’ve tried to decipher my mode of engagement with poetry and it seems to be primarily a function of empathy or phenomenological transference with the poet I’m reading. The greatest thing about your and Patrick’s poetry in that respect is that your poems seem trustworthy. You can immerse in them forever, safely, and are no worse, and often better for the effort. That “better” can range from learning a vocabulary word you didn’t know before to dreaming you have daughter, as I dreamed the night after I read “Erlkonigin.” Not so with the confessionalists. Here is one minor product of my two-week sojourn into their body of work:

Good Coffee

When I disintegrate it’s like some glass had broken.

Who wants to touch it? No, you sweep

The shattered life. A dust pan helps.

The liberal dumps it in a cell and calls

The welfare clerk. DSM for life.

The conservative hands me in a bag to

Trustee relatives, and,

Because my shards are bright

As an ex-wife’s faux-diamonds,

Includes free sticky glue.

Not my brand but soon enough

The cup is good as new

I pour in the losses,

Sip the anguish and pain

Full to the brim of time.

Mmmm. Good coffee.

Thank God I was only there two weeks. By contrast, I am currently channeling another one of Patrick’s poems and that is plain fun. Snowboarding, with a little love on the side.

Go Patrick!

LikeLike

Very interesting thoughts, Cliff. My frequent worry is that my interest in philosophy, science, and rationalism has given me TOO much control of my imagination. Rationalism, especially, in its promotion of things like reductionism and Bayesianism, makes it difficult to transfer clear thought into images, metaphors, allegories, etc. that can evoke that thought. In that respect, I’m very, very far behind poets like Blake, Stevens, Yeats and Merrill that developed their own symbolic systems and worked them into their poetry. That said, Donne has also been a big influence in convincing me that you can make great poetry out of a more abstract, direct mode of philosophical investigation.

What you say about your engagement with poetry being a function of “empathy or phenomenological transference” is, I’d guess, probably true of most poets. If you were to go through my poetry chronologically you could probably guess what poets I’d been reading around any given time because of the (often humiliating) attempts at imitation. One of my first poetic models was Milton, and I attempted my own mini Miltonic epic within my first year of writing poetry (and it came off as well as you can imagine such an endeavor coming out!). I do think there is something to be learned from the confessionalists in how deeply one’s personal experience can be mined for content, but at the same time, I think you’re right that there’s a lack of “art” that limits most of their poetry. Even when I find Lowell and Berryman (or, in a more contemporary fashion, Gluck) fascinating, I rarely find them eternally memorable or, as you suggested, find myself better from the experience.

Your Good Coffee piece is a good example of what I mean about there being some interesting content but which is in need of greater organization. I think what happens in confessionalism is that the method of “self mining” focuses one’s internal eye on the details, and even though those details can often be high quality material, there’s a lack of macro-organization, a structure, a “forest” made of the “trees.” My go-to method for structure is one borrowed from the sonata form of classical music: exposition, development, recapitulation. I’ll introduce a theme, develop it somehow, and then bring it back by the end. You can definitely see this at work in my piece above. It’s a principle I often worry I rely on TOO much, and have been hoping that I can find others that are equally as potent but without being so obvious.

LikeLike

[[My frequent worry is that my interest in philosophy, science, and rationalism has given me TOO much control of my imagination.]]

Not to worry, Jonathan. Without philosophy Stevens would have probably written more like Whitman. Indeed, his “repressed Whitmanism” has been commented upon by previous critics. But he also shares the compression you see in Dickinson, who loathed Whitman btw. In any case, both seem to have imitated Whitman by way of their repulsion to him. As for me, the tons of philosophy/psychology I’ve read (and forgotten) perhaps indexed by imagination but never really suppressed it. Paradoxically, my rampant fantasy life has probably made me more conservative—though I have yet to share Stevens’ documented admiration for Mussolini. I do know that, unlike a few of my friends, the last thing I need is weed, coke, or even Budweiser to stoke it. Indeed, some of them would need heavy doses of LSD and psilocybin to access what I am privy to just by voting a straight republican ticket.

So Philosophy? Good for you! In fact, I just used Bayesianism to fix my mower.

LikeLike

Fair enough on the Rosen quote. I didn’t mean Beethoven ONLY reacted against classicism, but certain works did (like the 6th Symphony) and these ARE often seen as the pieces that lead to the more revolutionary aspects of later romanticism. I actually think Beethoven’s achievement is not unlike that of Schumann and Brahms, namely that he was able to progress without (typically) abandoning the old forms completely. That something so radical and modern like his Grosse Fugue was done in such an old form is a testament to this point.

[[[I was thinking of modernism’s influence in terms of form and structure ]]]

Once you get to the “everything goes” philosophy of free verse, it seems there’s a pretty set binary between it and classic verse. I’d certainly grant modernism’s influence on that front.

[[[Your reasoning, as to why so few know or read post-modern poetry might be sound if it didn’t fail to explain why so many of these same contemporary readers are intimately familiar with modernist poets ]]]

The original modernists came to prominence before the dominance of new media. Film and recorded music were in their first steps towards maturation when The Waste Land, Harmonium, and The Tower were released. Many years away from comics, TV, video games, and the internet, not to mention home video.

[[[good luck trying to find their music or the poems of Dryden or Pope at your average bookstore. ]]]

Who cares about your average bookstoore these days!? Amazon.com has cultivated my snobbishness! :D I just finished up the complete keyboard works of Couperin, so I can sympathize.

LikeLike