My long two pointed ladder's sticking through a tree Toward heaven still, And there's a barrel that I didn't fill Beside it, and there may be two or three 5 Apples I didn't pick upon some bough. But I am done with apple-picking now. Essence of winter sleep is on the night, The scent of apples: I am drowsing off. I cannot rub the strangeness from my sight 10 I got from looking through a pane of glass I skimmed this morning from the drinking trough And held against the world of hoary grass. It melted, and I let it fall and break. But I was well 15 Upon my way to sleep before it fell, And I could tell What form my dreaming was about to take. Magnified apples appear and disappear, Stem end and blossom end, 20 And every fleck of russet showing clear. My instep arch not only keeps the ache, It keeps the pressure of the ladder-round. I feel the ladder sway as the boughs bend. And I keep hearing from the cellar bin 25 The rumbling sound Of load on load of apples coming in. For I have had too much Of apple-picking: I am overtired Of the great harvest I myself desired. 30 There were ten thousand thousand fruit to touch, Cherish in hand, lift down, and not let fall. For all That struck the earth, No matter if not bruised or spiked with stubble, 35 Went surely to the cider-apple heap As of no worth. One can see what will trouble This sleep of mine, whatever sleep it is. Were he not gone, 40 The woodchuck could say whether it's like his Long sleep, as I describe its coming on, Or just some human sleep.

·

- Interestingly, in Robert Frost’s reading (or memorization) of the poem, the line: “Cherish in hand, lift down, and not let fall…” is spoken as “Cherish in hand, let down, and not let fall.”

After Apple-Picking is one of Robert Frost’s great poems and among the greatest poems of the 20th century. The first thing I want to do is to revel in the structure and form of the poem. I’ve seen several references made to Rueben Brower’s analysis of the meter in this poem, and all the  sources concur in calling Brower’s analysis a tour-de-force. I have not read Brower’s analysis and won’t until I’ve done my own. I love this sort of thing and don’t want my own observations being influenced. So, if there are any similarities, I encourage you to conclude that fools and great minds think alike. Here we go. First, T.S. Eliot:

sources concur in calling Brower’s analysis a tour-de-force. I have not read Brower’s analysis and won’t until I’ve done my own. I love this sort of thing and don’t want my own observations being influenced. So, if there are any similarities, I encourage you to conclude that fools and great minds think alike. Here we go. First, T.S. Eliot:

“The most interesting verse which has yet been written in our language has been done either by taking a very simple form, like iambic pentameter, and constantly withdrawing from it, or taking no form at all, and constantly approximating to a very simple one. Is this contrast between fixity and flux, this unperceived evasion of monotony, which is the very life of verse… We may therefore formulate as follows: the ghost of some simple metre should lurk behind the arras in even the ‘freest’ verse; to advance menacingly as we doze, and withdraw as we rouse. Or, freedom is only truly freedom when it appears against the background of an artificial limitation.”

Eliot could have been describing Frosts’s After Apple-Picking (though he doesn’t say). Despite the appearance of free verse (which it is) Frost’s poetry moves toward and away from a regular meter, and into and out of rhyme, so that the arrhythmia of free verse and the rhythm of meter co-exist and beautifully blend.

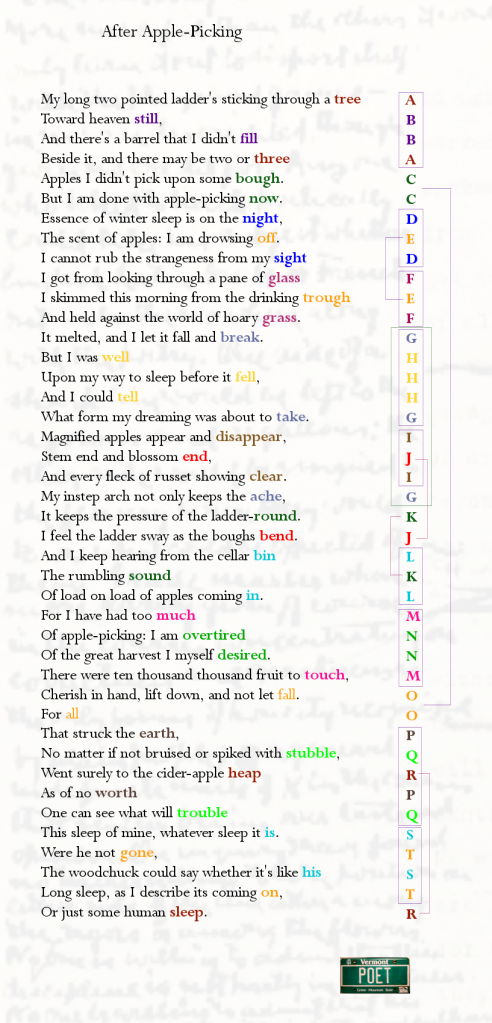

- Unmarked feet are iambic. Yellow is pyrrhic (which I will never learn to spell). Purple is spondaic. Red is trochaic. Green is an amphibrachic foot (called a feminine ending when closing the line).

Worth noting is that the poem is, allowing for the usual variant feet, as iambic (if not more so) than many of his more “regular poems”. The difference is in line length. The alternate lines are trimeter, dimeter and one monometrical line. There are no alexandrines however. Frost seemed unwilling to extend the line beyond iambic pentameter. I listened to Frost’s own reading of the poem so that the scansion would more accurately reflect what he had in mind. Interesting to me is the fact that Frost, when he reads at least, prefers to emphasize the iambic lines. For instance, I was initially tempted to scan the following line as follows:

One can see |what will trouble

That’s two anapests, the second has a feminine ending. Frost, however, reads the first four syllables with an almost equal stress:

One can see what will trouble

This makes me more apt to scan the line as trimeter with two strong spondees:

One can |see what |will trouble

It may be reading too much into Frost’s performance (since he tends to emphasize the iambics in many of his poems) but the poems hard, driving iambics lend the poem an exhausted, relentless feel that well-suits the subject. There is no regular rhyme scheme, but there is a sort of elegant symmetry to the rhyming that’s easier to see with some color and some visual aids.

My own feeling is that one has to be careful when ascribing too much intentionality to the poet. How much of this rhyme scheme was the result of deliberate planning and how much arose naturally as the poem progressed? In other words, I grant that none of the rhymes are accident, but I doubt that Frost sat down in advance to build his poem around a rhyme scheme. The poem has the feeling, especially given the shorter (almost opportunistic) line lengths, of a certain improvisation. When he needed to rhyme earth, he cut short a line (making it dimeter) to end up with “As of no worth”. On the other hand, I don’t think it’s coincidence that we find bough/now just after the start of the poem, and fall/all shortly before the poem finishes. In the middle, as though bracketed by these two couplets, is the triple rhyme well/fell/tell. The effect is to nicely divide the poem and give a certain symmetry.

The last element to include is the phrasing, something I haven’t done in other poems, but will try to elucidate in this one. Part of the art of poetry, too often overlooked, is the achievement of phrasing that, at its best, mimics human speech. We don’t tend to speak in one long sentence after another and we don’t favor an endless stream of short sentences (unless “dramatic” circumstances call for it). Not only was Frost keenly interested in the colloquial voice, but also understood the importance of phrasing, of the give and take of normal speech. A mistake that many beginning poets make, in their effort to so much as fit their ideas into the patterns of rhyme and meter, is to sacrifice a naturalness in their phrasing. A telltale feature of such writing is a poem dominated by end-stopped lines — syntax and phrasing that slavishly follows the line.

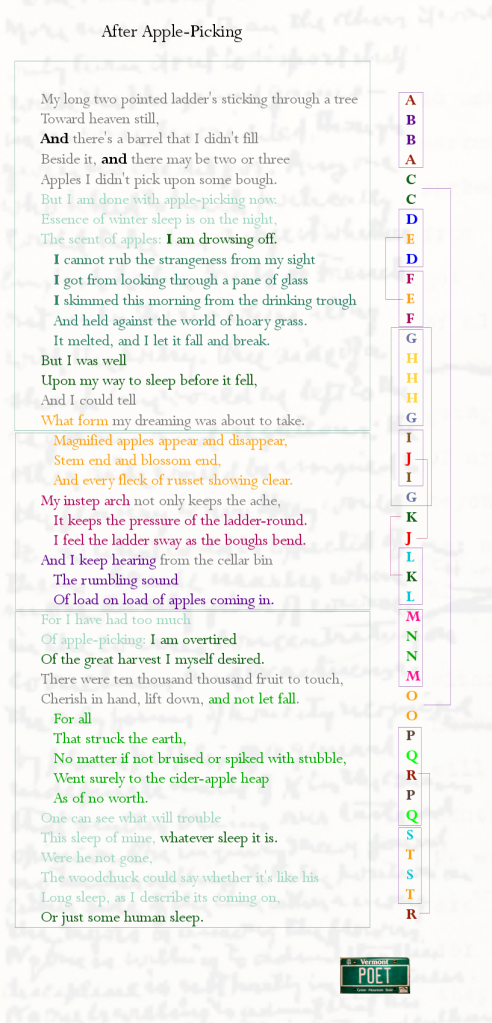

So, what I’ve done is to color code what I perceive to be the rhetorical structure of the poem. I’m iffish on a couple details, but let’s get started. The fist five lines are a simple, declarative sentence. Frost (I’ll refer to the speaker as Frost) begins the poem with a scheme called the Italian Quatrain. This only means that the rhyme scheme follows an abba pattern one would find in Petrarchan sonnets. ( I don’t, for an instant, suggest that Frost was thinking to himself: I shall now write an “Italian Quatrain”.) I do mean to suggest that the quatrain has a certain closed feel to it. But the poem isn’t done and neither is the work of apple-picking. In the fifth line there are some apples “still upon some bough” and there is new rhyme, bough, dangling like an unpicked apple.

Frost turns inward:

6 But I am done with apple-picking now. Essence of winter sleep is on the night, The scent of apples: I am drowsing off.

The light green and “Dartmouth” green (couldn’t resist calling it that) signify the moments when Frost’s gaze turn inward. This happens four times in the poem. Whereas the first five lines are comprised of syndetic clauses (clauses linked by the conjunctive and), the second clause, the  turning inward from the orchard (which places the poem) to Frost’s exhaustion, is asyndetic. The first five lines, with their repeated and’s are the way we speak (and you’ll even notice it in children) when we want to express the idea of endlessness. We might say: I have this and this and this and this to do. In a similar sense, Frost wants to communicate the endlessness of this chore. The first five lines are a rush of description.

turning inward from the orchard (which places the poem) to Frost’s exhaustion, is asyndetic. The first five lines, with their repeated and’s are the way we speak (and you’ll even notice it in children) when we want to express the idea of endlessness. We might say: I have this and this and this and this to do. In a similar sense, Frost wants to communicate the endlessness of this chore. The first five lines are a rush of description.

When his gaze turns inward, to his own exhaustion, the lines become asyndetic. The fifth line, introducing a new rhyme, is complete in and of itself. The syntax, I think, mirrors Frost’s own exhaustion. The sentences are short. Clauses are no longer linked by conjunctions (they could be).

But I am done with apple-picking now.

By rights, one could pause after that line as though to catch one’s breath. The pause is reinforced when the line completes the rhyme of bough with now, as if Frost had picked the apple. In some ways, one could stop the poem here. The rhymes are complete. We have an Italian Quatrain followed by a concluding couplet. In a sense, the first six lines are the larger poem in miniature. “Essence of winter sleep,” not just the sleep of a night, already hints at a longer hibernation. From there Frost sleepily stumbles onward and the rhymes, like unpicked apples, will draw him. The sentences become progressively shorter as though Frost’s ability to think and write were as curtailed as his wakefulness. The eighth line ends with the simple, declarative, “I am drowsing off.” There’s nothing poetic about such a line or statement; and that’s part of its beauty and memorableness.

- An apple ladder is usually tapered, much narrower at the top than bottom. This makes pushing them up through the limbs much easier. Some are joined, like the ladder in the picture, while others are not. Frost’s ladder was “two pointed”, and so not joined at the top. The ladder going up to my daughter’s loft is an old apple ladder.

The next six lines, beginning with “Essence of winter sleep…” are another set of interlocking rhymes DEDFEF

7 Essence of winter sleep is on the night, The scent of apples: I am drowsing off. I cannot rub the strangeness from my sight 10 I got from looking through a pane of glass I skimmed this morning from the drinking trough And held against the world of hoary grass.

The rhetorical course of the poem links lines 6-8 while the rhyme schemes of lines 1-6 and 7-12 are separate. There is an overlap between the subject matter (in green) and rhyme scheme (purple).

The overlap draws attention away from the rhyme scheme (at some level, I think, disorienting the reader). I know I’m flirting with Intention Fallacy, so I’ll try not to draw too many conclusions as to Frost’s intentions when writing a given rhyme scheme. However, whether he wrote these lines on purpose or instinctively, they produce a similar effect in this given poem. The poem’s rhetorical structure, which doesn’t always mirror the rhyme scheme, draws our attention away from the rhymes and may contribute to any number of the poem’s effect, including the feeling of exhaustion. At its simplest, the crosscurrents of rhetoric and rhyme, I think, help to create an organic feeling in the poem — the feeling that it’s not a series of stanzas knit together.

The overlap draws attention away from the rhyme scheme (at some level, I think, disorienting the reader). I know I’m flirting with Intention Fallacy, so I’ll try not to draw too many conclusions as to Frost’s intentions when writing a given rhyme scheme. However, whether he wrote these lines on purpose or instinctively, they produce a similar effect in this given poem. The poem’s rhetorical structure, which doesn’t always mirror the rhyme scheme, draws our attention away from the rhymes and may contribute to any number of the poem’s effect, including the feeling of exhaustion. At its simplest, the crosscurrents of rhetoric and rhyme, I think, help to create an organic feeling in the poem — the feeling that it’s not a series of stanzas knit together.

- I’ve probably mentioned this before, but there’s a good article on the 4 deadly fallacies in the New York Times. The editorialist, Christopher Lehmann-Haupt offers up another take on the Intention Fallacy with this nice little anecdote:

”Are you trying to tell me that I don’t know what I’m doing when I paint?” ”Well, not exactly . . . ,” I began. ”My God,” he roared, ”every time I put a brush to a canvas, I have an intention. And I damn well better know what it is, or else the painting ain’t gonna be any good.” He rolled his eyes. ”Intentional fallacy,” he muttered. Then with a weary sigh: ”What do these critics think art is? Monkeys dabbling? Art is nothing but decisions. Decisions, decisions, decisions.”

My response Ben Shahn’s outrage would be to point out that it’s all well and fine for the artist (or poet) to indignantly claim an intention behind every brush stroke, line break or stanza break. It’s another to expect the reader or critic to guess it right. This issue is what was behind the failure of Charles Hartman’s Free Verse, An Essay on Prosody. Hartman was essentially (in my opinion) trying to turn every line break into a prosody of free verse. The problem is that a prosody depends on the reader correctly guessing an author’s intention. Without that, all you’ve got is a game of Russian roulette called Intention Fallacy.

The rhyme scheme of DEDFEF forms a sexain, but Frost’s thoughts veer beyond it.

Just as before, there is one line more than the rhyme can bear: “It melted, and I let it fall and break.” Once again, the analogy of the unpicked apple comes to mind. Is this the analogy Frost had in mind? To say so would be an Intention Fallacy, but I think the analogy works in the context of the poem. Anyway, we’re left with an unresolved rhyme.

But Frost has other matters to address. As if remembering the course of his poem after an aside (a wonderful and colloquial technique that appears in many of his poems – Birches) he seems to gather his resolve with three rhyming lines, short and quick.

But I was well 15 Upon my way to sleep before it fell, And I could tell What form my dreaming was about to take.

Take resolves the hanging rhyme of break. For a moment, both the poem’s rhetorical course and the rhyme scheme meet. There is a moment of resolution before Frost’s dreaming overtakes the poem, and with it an interlocking set of rhymes that don’t find resolution until line 26.

25 The rumbling sound

Of load on load of apples coming in.

At this point, the poem will once again pivot. Here’s another image to help visualize what I’m describing.

In terms of rhyme and rhetoric (in the sense of concluding thought and concluding rhyme) the poem could be divided into three parts. Until then, subject matter and rhyme overlap in a way that, to some extent, might subliminally propel the reader.

Magnified apples appear and disappear,

Stem end and blossom end,

20 And every fleck of russet showing clear.

My instep arch not only keeps the ache,

The word end like the stem end of an apple (or itself another unpicked apple) won’t find it’s blossom end until the next three lines that are (now this gets really cool) the only three lines where an identifiable rhyme scheme isn’t matched to subject matter. That’s to say, most of the other rhymes come in tercets and quatrains (look at the boxes surrounding them). It’s only in the weightless center of the poem where any sort of identifiable scheme more or less breaks down. There’s a kind weightlessness, right after the dreaming and at the center of the poem, seems almost meant to imitate the dreaming exhaustion of the poem itself. I would love to think he did this on purpose.

- I’ve suggested that other poems by Frost can be understood, beneath their surface, as extended metaphors for the writing process. Some others are much more transparently about writing (as much as saying so), so I don’t think such speculation is without merit (though I realize I could be accused of playing the same ace of spades with each hand). After Apple-Picking could easily be read as analogous to the writing process itself — apples being understood as poems. Frost, by this point in his career, may have been feeling like writing poetry was like picking apples. While Frost didn’t think much of Yeats’s description of writing as “all sweat and chewing pencils” he also stated that after getting paid for the first poem he found he couldn’t write one a day for an easy living: “It didn’t work out that way”. Poems were like apples, it turned out. One couldn’t just shake the tree and let them fall. Doing that would leave them “bruised or spiked with stubble”, which is another way, perhaps, of saying that the hurried poem would be the flawed poem. They had to be cherished. Writing the poem, imagining its landscape of imagery, perhaps was like looking through “a pane of glass… skimmed… from the drinking trough/And held against the world of hoary grass.” Looking at the world through a poem is, perhaps, a bit like looking at the world through ice, a distortion that is both familiar and strange.

21 My instep arch not only keeps the ache,

It keeps the pressure of the ladder-round.

I feel the ladder sway as the boughs bend.

Ache remembers the rhyme of break and take, but is far removed and seems more like a reminder than part of any rhyme scheme. Round is new, and sends the ear forward with the expectation of a rhyme. Bend turns the ear back, remembering end (is far removed as ache from take). The poem “sways”, in its center, like the ladder. The reader is never given the opportunity to truly settle in with any kind of expectation, but like the speaker of the poem, is drawn forward in search of a rhyme’s “blossom end” and, with the next line, is drawn back to a different rhyme’s “stem end”. Rhymes are magnified, appear, then disappear.

- Notice too how Frost divides the central portion of the poem into three of our five (or seven) senses.

SIGHT What form my dreaming was about to take. Magnified apples appear and disappear, Stem end and blossom end, And every fleck of russet showing clear. TOUCH/SENSATION/KINESTHETIC My instep arch not only keeps the ache, It keeps the pressure of the ladder-round. I feel the ladder sway as the boughs bend. SOUND And I keep hearing from the cellar bin The rumbling sound Of load on load of apples coming in.

Earlier, Frost touched on the sense of smell with the “scent of apples”. The point here is that part of what makes this poem so powerful are the concrete images and the evocation of our senses. Don’t ever forget this in your own poetry. I know I’ve written it before, but it bears repeating: remember each of your senses when you are writing poetry. Don’t just focus on sight (which the vast majority of poets do) but think about sound, smell, touch, movement, texture, etc… Notice too, how Frost turns the ordinary into some of the most beautiful poetry ever written. There are no similes to interrupt the narrative. There are no overdrawn metaphors. Frost makes poetry by simply describing and evoking the every day; and doing so in ordinary speech. The rhyme scheme knits the poem together in an organic whole. Think how much less impressive the poem would be if it were simply free verse, free verse as it’s written by the vast majority of contemporary poets.

Notice Frost’s thought-process. He muses over “what form” his dreams will take, then expands on it (in yellow). He mentioens the ache of his instep arch, then expands on that (in lavender), then describes what he hears from the cellar bin (in purple). It’s a nice way of writing that reminds me of the rhetorical figure Prolepsis (or Propositio) in Shakespeare’s To be or not to be….

With coming in we arrive at the third portion of the poem.

For I have had too much Of apple-picking: I am overtired Of the great harvest I myself desired. 30 There were ten thousand thousand fruit to touch, Cherish in hand, lift down, and not let fall. For all -- That struck the earth, No matter if not bruised or spiked with stubble, 35 Went surely to the cider-apple heap As of no worth. One can see what will trouble -- This sleep of mine, whatever sleep it is. Were he not gone, 40 The woodchuck could say whether it's like his Long sleep, as I describe its coming on, -- Or just some human sleep.

Frost turns inward again.The phrase, “I am overtired…” reminds us of his previous declarative statement “I am drowsing off”, inviting a sense of symmetry and closure. This time, though, Frost won’t digress. He is overtired of the great harvest. He will plainly say what exhausts him and why. The rhyming couplet fall/all adds to the sense of symmetry, hearkening back to the couplet bough/now. In both subject matter and form, Frost is recollecting himself. Again, it’s a similar structure to Birches — an assertion, a digression, and a concluding restatement of the original assertion.

The closing rhyme scheme of lines 33-41 is essentially comprised of two Sicilian Quatrains, the same that characterize the Shakespearean sonnet. However, the first Quatrain is interrupted by heap. You can see it above in the overall rhyme scheme (at the beginning of the post), but also directly above. It’s as if the poem is coming out of a sort of fever, a confusion of consciousness, and back to order. The rhyme heap/sleep might have been the concluding couplet in a Shakespearean sonnet, but that kind of epigrammatic finality would have been out of place in a narrative poem like this. Instead, the word heap slips into the first quatrain, another new sound, and the ear perhaps subliminally or subconsciously looks for the rhyme, but it doesn’t come. We finish the first of the two quatrains without it.

With the second quatrain of this third section:

This sleep of mine, whatever sleep it is. Were he not gone, 40 The woodchuck could say whether it's like his Long sleep, as I describe its coming on,

The speaker seems almost recovered from the confused reverie of the poem and once again the poem’s beautiful symmetry is upheld. The poem begins with a Sicilian quatrain and all but closes with a Sicilian quatrain. But there is still one loose-end, one apple that has not been picked. Frost metaphorically picks it in the last line.

Or just some human sleep.

It’s a beautiful moment. The line is short and simple. It’s shortness may remind the reader of the speaker’s own weariness. He doesn’t have it in him to compose a fully Iambic Pentameter line. His sleep may just be some human sleep, and nothing more.

- Frost asks whether his sleep will be like that of the woodchuck’s. The comparison seems almost like a moment of levity after so much profundity. Some critics throw all their weight into these last 5 lines. Because sleep is repeated several time, Conder (as is the habit with some critics I have noticed), take this to mean that “sleep” must be central to the poem’s meaning and that all other considerations are mere trivialities. As example, consider John J. Conder’s analysis of After Apple-Picking. There, you can also find a collection of other essays on the poem. Personally, Conder’s analysis makes my eyes badly cross. Almost every sentence seems like a Gordian Knot. Here’s an example:

And now you don’t have to read the essay. (You can thank me by e-mail.) You’d think the poem should have been called: Before Going to Sleep. My point, besides having a little fun at Conder’s expense, is to argue that it’s possible to read too much into Frost’s comparison of his sleepiness to that of the woodchuck’s. My own feeling is that he’s not suggesting a sweeping metaphor of man, sleep and nature, but that the analogy is what it is. He’s overtired. He’s almost feverish with exhaustion and speculates that the only sleep to recover from that kind of weariness (the weariness of a whole season of apple growing) might be a whole season of sleeping – the hibernating sleep of a woodchuck. It’s an earthy, slightly sardonic, reference in keeping with the colloquial tone of the poem.

And now you don’t have to read the essay. (You can thank me by e-mail.) You’d think the poem should have been called: Before Going to Sleep. My point, besides having a little fun at Conder’s expense, is to argue that it’s possible to read too much into Frost’s comparison of his sleepiness to that of the woodchuck’s. My own feeling is that he’s not suggesting a sweeping metaphor of man, sleep and nature, but that the analogy is what it is. He’s overtired. He’s almost feverish with exhaustion and speculates that the only sleep to recover from that kind of weariness (the weariness of a whole season of apple growing) might be a whole season of sleeping – the hibernating sleep of a woodchuck. It’s an earthy, slightly sardonic, reference in keeping with the colloquial tone of the poem.

Thorough exegesis, wow. I took much of this poem for granted, but have a massively greater appreciation for it now. Tying rhyme, meter, versification, and theme together was incredibly insightful.

LikeLike

Glad you enjoyed it Jack. I’ve been meaning to write this post for years, but was always too intimidated to try. The poem’s a masterpiece.

LikeLike

I’m impressed with your analysis, Patrick. You’ve brought to light many things I’d noticed but never considered in any depth. Thank you for this. One minor point: In your metrical overview, I’m curious about the two feet you’ve called anapests. To my ear, the “stubble” line is iambic with a feminine ending. The “trouble” line is a little more troubling prosodically. My feeling is that this is iambic trimeter with a feminine ending (though the difference in stress between the syllables in the first two feet is slighter than in the third foot).

LikeLike

Hi Steven. Thanks for reading closely. I mislabeled green as being anapestic. I just changed that — should be amphibrachic (feminine ending), as you say. On the second line, what you’ve suggested is the way I scanned it: iambic trimeter with a feminine ending. It’s possible I called it something else? — but that was one of the line’s I discussed (and also the way Frost reads it). :-)

LikeLike

Thanks for one more of your enlightening posts!

Very little by Frost is interpreted into my mother language Swedish. Only one little pamphlet with a translation of “North of Boston”. “After Apple-Picking” poem happens to be in that collection though – and it is available in the major public libraries! :-)

It could be a nice exercise to try to interpret some of Robert Frost’s poems to Swedish! He is a wonderful poet.

LikeLike

I can’t imagine what Frost would sound like in Swedish (or any language for that matter). One of the unique qualities of Frost’s poetry is his ear for the sound of phrasing — the way we inflect words and phrases. He used to say that even if we couldn’t hear the words, the “sound of sense” (or the sound of the phrases and the way they’re spoken) would tell us much about how a thing is being discussed, whether happy or sad, or hurried or calm. I can’t imagine how that quality (that musicality of phrasing) might be translatable from one language to the next. I could imagine that Frost must sound quite plain and ordinary to the non-English speaking reader. If you translate any of Frost’s poems, I will happily post them here, as part of the post. :-)

LikeLike

Pingback: Plocka äpplen | Stänk och flikar

You are right, of course, most poetry is not possible to translate. The interpreter has to write a “new” poem inspired by the original and it takes a good poet to accomplish that. (I certainly do NOT think that I could do that. But it would be nice to try …)

Swedes read Homer, Sapho, Racine, Petrarch, Shakespeare, Keats, Goethe, Schiller, Akhmatova, Adunis, Bashō, etc., interpreted into Swedish. We, who speak a small language, would be so poor if we didn’t have this access to the poetry of the world, even if the poems we read are merely reflections of the original. – There is so much to say about this and little space.

If you don’t mind, I will give you my opinion of “North of Boston” in Swedish when I have read it.

LikeLike

Well, but if you do try, and if you’re willing, I’ll happy to post your translation (or any translation for that matter). I think you should. Who knows, but maybe another of your compatriots will read your translation, appreciate it, and add their own touches? As to “North of Boston”, I’m equally happy to link to anything you write. I would do that for any writer, poet or translator.

LikeLike

Pingback: Går det att översätta poesi? Några funderingar … | Stänk och flikar

Pingback: Plocka äpplen – Gamla Stänk och flikar

Pingback: Går det att översätta poesi? Några funderingar … – Gamla Stänk och flikar