Sonnet 42

What lips my lips have kissed, and where, and why,

I have forgotten, and what arms have lain

Under my head till morning, but the rain

Is full of ghosts tonight, that tap and sigh

Upon the glass and listen for reply,

And my heart there stirs a quiet pain

For unremembered lads that not again

Will turn to me at midnight with a cry.

Thus in the winter stands the lonely tree,

Nor knows what birds have vanished one by one,

Yet knows its boughs more silent than before:

I cannot say what loves have come and gone,

I only know that summer sang in me

A little while, that in me sings no more.

Edna St. Vincent Millay

Edna St. Vincent Millay, for a great many poets and critics, challenges notions of greatness. What defines a great poet? – What in her person and what in her poetry? One almost wishes photographs of Millay had never been taken or never survived. In her New York Review of Books review of Millay and Millay’s reviewers, Lorrie Moore quotes some of Daniel Mark Epstein’s (What Lips My Lips Have Kissed) more lascivious biography:

[Epstein] is a little startling, for example, on the subject of Millay’s naked breasts, about which he exults–photographs of which he has apparently poured over in the files of the Library of Congress (which cannot authorize their release and reproduction until the year 2010). When he gives us his own feverish descriptions, readers may become a little frightened, but eventually he moves on, and I do believe everyone recovers. Such an instance does not , however, prevent him from other periodic overheatings (“Her coloring, the contrast between her white skin and the red integuments, lips, tongue, and more secret circles and folds her lovers would cherish, had become spectacular after the girl turned twenty.)

On the one had, one might argue that Epstein is writing about Millay’s Loves and Love Poems and so is entitled to this sort of fetishistic “field research”, but one has to wonder whether Epstein would apply the same zeal to the skin color and “secret folds” of Robert Frost or E.E. Cummings were he to write a book about their love poetry.

What a writer like Epstein conveys, wittingly or unwittingly, is the bewitching effect Millay’s self-evident beauty had on both men and women (who were also among her lovers). Would her poetry have received the same attention if she had looked like Tina Fey on one of her comedic bad days? Would estimation and discussion of her poetry’s greatness (which some refute) be any different?

As it is, discussions of her poetry almost always includes discussions of her personality, beauty, and love affairs (including this post). And, to be fair, Millay’s life and poetry are intricately intertwined in a way that is not as evident with other poets. One always gets the sense that her poetry is mischievously auto-biographical. She writes about herself. And the best poets, in my opinion, are frequently the ones with skeletons in their closets. In Millay’s case, the plush carpet between her bed and closet is well worn. If I had been around during Millay’s youth, I probably would have been just as smitten as the rest of them (and hanging in her closet).

Moore, at the start of her NY Review of Books article, writes:

She was petite, in-tense, bright, witty, romantic, freckled, auburn-haired, self-dramatizing and beautiful. (As a poet friend recently remarked to me, “Why has Judy Davis not yet played her in the movie?”) At one time arguably the most famous living poet in the world, her work lauded by Thomas Hardy, Elinor Wylie, Edmund Wilson, Sarah Teasdale, and Louse Bogan, Millay lived stormily and wrote unevenly, so that her place in American letters was in descent even in her lifetime. In her day she was hailed as a feminist, lyric voice of the Jazz Age, yet she went largely unclaimed by the feminism of subsequent decades. She owned, perhaps, too many evening gowns. And her poems may have had an excess of voiceless golden birds (she did not strain her metaphors… Her work could be occasionally modernist, but only occasionally, and so was not taken up by the champions of modernism…

But Millay has her champions and continues to have her admirers. Deservedly so. She lived life large. She was unapologetic about her proclivities and a fiercely independent woman when, in many ways, women were still treated like guileless children. She was the poet’s poet. She spoke directly and truthfully in her poetry, anticipating the women poets of the later 20th century.

Millay’s Legacy

This is my third go around with this section. I think, like many other readers, poets and critics, I ask myself: Why am I reading her? Is she a great poet who wrote mediocre poems, or was she a mediocre poet who manged to write some great poems?

Now that I’m rewriting this for the third time, I think I’ve got a fix on all of this. Lorrie Moore, in her NY Review of Books article, refers to Millay as a “skilled formalist”. Skilled is probably a good adjective. Micheal Haydn (the composer and brother of the genius Joseph Haydn) and JC Bach (the son of the great JS Bach) were both skilled composers. They both wrote some incredibly catchy and occasionally, deeply expressive music, but neither was a genius and neither will ever be counted among the greats. Not familiar with classical music? Take REM. REM is a skilled rock band. They may have written one or two great songs, but nobody, fifty years from now, will include them among the great bands. And I’m not the only one who holds that opinion.

So, skilled is a measured way to describe Millay’s formalist abilities.

So, skilled is a measured way to describe Millay’s formalist abilities.

She could write the perfect sonnet. She was an avowed master, and I do mean master, of the rhyming couplet, most typically in the form of the epigrammatic sting that frequent and succinctly closes her Shakespearean Sonnets. No other 20th Century poet even distantly approaches the sly and witty ferocity of Edna St. Vincent Millay’s rhymes. But her skill as a formalist only went so far.

She rarely modulates her formalism to suit the subject matter. One gets the feeling that she paid more attention to the prettiness of the line, than to its aptness. Despite the mood, whether it was rage, sorrow, delight, or fear, there is a sameness of voice to all of her poems. By way of comparison, compare Robert Frost’s Mending Wall to Birches. While there is a certain sameness to every poet’s output, some poets are able to master a greater technical range than others. Birches and Mending Wall both sound like Frost, but both show a distinctly different approach in imagery and, more specifically, formal devices. When at his best, Frost modulated his voice to suit the subject matter.

One doesn’t get the same sense from Millay.

And that has a curious effect, at least to me. The skilled and elevated diction of her formalism makes her trivial poems seem better than they are, and her more profound gestures feel less profound. So, in my own appraisal of Millay, I would consider her a major poet, though not great. She was a skilled formalist, but possessed a very limited range.

And it’s in that respect that I disagree with criticism that calls her style anachronistic. Returning to Moore’s NY Review of Books article, she writes:

A gifted formalist and prolific sonneteer, a literary heir to Donne, Wordsworth, Byron, and, well, Christina Rossetti, Millay today has been admired only slightly or reluctantly, if at all, her poetry viewed, sometimes by its detractors as well as its devotees, as anachronistic, unreconstructedly Victorian, sentimental, recycled. Even the critic Colin Falck, who writes in his ardent introduction to her Selected Poems that the “occulting of Millay’s reputation has been one of the literary scandals of the twentieth century,” nonetheless finds only a quarter of her poems worthy enough “to entitle her to consideration as one of the major poets of the country.”

Millay was born in 1892 which means, like other poets of her generation, she grew up with the poetry of the great Victorians ringing in her ears. Tennyson died the same year she was born. Robert Browning had only been dead three years. Christina Rossetti lived until 1894. Their legacy and presence was still profoundly felt. In short, when Millay began writing, the 19th century’s aesthetic was not anachronistic.

Millay’s shortcoming was not that she was writing formal poetry when the vast majority of her generation (and later) had adopted free verse. Her shortcoming was that her formalism defined her voice, rather than her voice defining her formalism. It can be difficult to discern which of Millay’s poems are her mature poems and which are the poems of her youth.

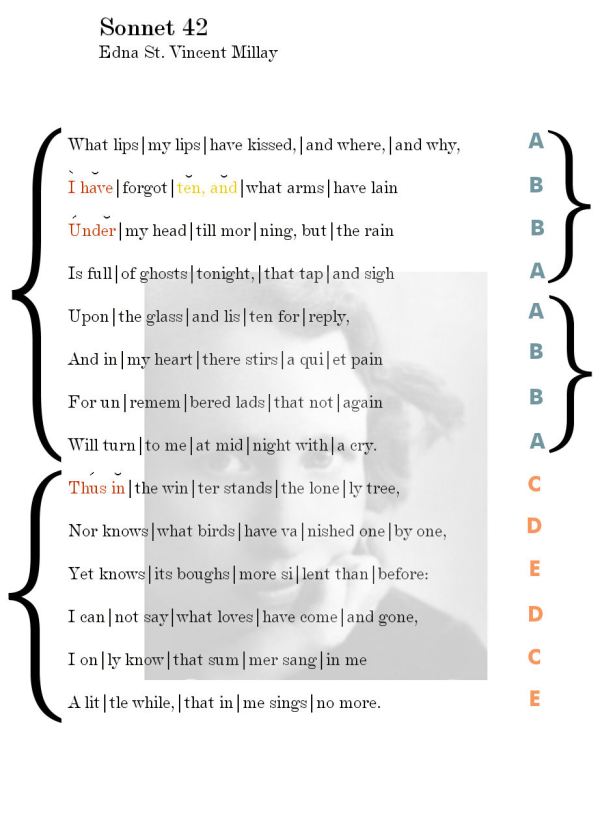

The Scansion

As is my habit, all unmarked feet are Iambic. The color coding is a visual aid, meant to help you quickly see how the poet has varied the given meter (in this case, Iambic Pentameter).

About the Meter and Structure of the Poem

Millay’s sonnet is firmly in the tradition of the Petrarchan Sonnet. The Sonnet is split into the Octave (the first 8 lines) and the Sestet (the last 6), both “halves” of the sonnet characterizing the traditional volta or turn of the Patrarchan Sonnet. The Petrarchan form is well suited to the contemplative subject matter. There is no argument. There is no epigrammatic summing up or sting (such as we find in a Shakespearean Sonnet).

The sestet deliberately avoids close rhymes creating, to my ear, a diffuse music that nicely matches the poems’ tone. The final rhyme more feels like a distant echo of before, like the echoes of her lovers. The more diffuse rhyme scheme also serves to further differentiate the sestet from the octave. The octave speaks to the loss of lovers. The sestet speaks to a deeper loss – her fading memory of them. “I cannot say what loves have come and gone…” she writes. The diffuseness of her memory is nicely echoed by the rhyme scheme (intentioned or otherwise).

The metrical style is characteristic of Millay. There are only three definite variant feet in the entirety of the poem. The first variant foot, which I marked as |I have| could also be read as an Iambic foot |I have|. I’ve searched for a recording of Millay reading this sonnet but haven’t found any. I have a hunch she would have read that first foot as an iamb. She was very conservative in her metrical daring.

In that respect her temperament is entirely that of a late Victorian, rather than that of an Elizabethan (with whom the sonnet form originated). The Elizabethans were always restlessly stretching and violating forms. They were the great explorers, both at sea and in literature – in just about everything they did. In that respect, Millay’s sonnet has almost nothing in common with them but a rhyme scheme.

And it’s in this respect that some critics wish Millay had stretched herself. I suspect she could have but preferred the contemplation and quiet dignity of an uninterrupted iambic line. Her rhyming is equally conservative, especially in light of Emily Dickinson’s poetry. The eye rhyme pain/again was probably pronounced as a full rhyme when Millay read the poem. (She was nothing if not affected when she read her poetry.) I considered reading this poem myself but I just can’t get beyond the absurdity of a man’s voice behind her words.

Here is Millay reading Sonnet 121:

Oh Sleep forever in the Latmian cave,

Mortal Endymion, darling of the Moon!

Her silver garments by the senseless wave

Shouldered and dropped and on the shingle strewn,

Her fluttering hand against her forehead pressed,

Her scattered looks that trouble all the sky,

Her rapid footsteps running down the west-

Of all her altered state, oblivious lie!

Whom earthen you, by deathless lips adored,

Wild-eyed and stammering to the grasses thrust,

And deep into her crystal body poured

The hot and sorrowful sweetness of the dust:

Whereof she wanders mad, being all unfit

For mortal love, that might not die of it.

[Audio=https://poemshape.files.wordpress.com/2009/09/millays-sonnet-121.mp3]

What does the poem mean?

The poem is beautiful in its simplicity – an effect that is surprisingly difficult to master.

But, having said that, I can’t help but wonder at another meaning. I’m not sure at what point in her career she wrote this sonnet, but I wonder if she’s not also describing her poetry. Think of the lads as poems and kisses as the act of writing the poems. If one reads the poem this way, she writes as poet who feels her powers waning.

Read in this light, the final sestet feels especially poignant. Millay stands as the tree in whom poetry used to flourish, but whose birds have flown, one by one. She can’t even remember what loves have come and gone. The inspiration of her youth fails her. The poems that used to come budding to her lips have all but vanished. She writes: “I only know that summer sang in me / A little while, that in me sings no more.”

The Sonnet Before the Sonnet

And now for some of that unmatched ferocity that Millay could summon up. When reading Sonnet 42 (when lost to its wistful beauty) it’s best to keep in mind the Sonnet that immediately preceded it. Which is the real Millay? Both, no doubt. In real life, biographers tell us that 41 would have come after 42.

Sonnet 41

I, being born a woman and distressed

By all the needs and notions of my kind,

Am urged by your propinquity to find

Your person fair, and feel a certain zest

To bear your body’s weight upon my breast:

So subtly is the fume of life designed,

To clarify the pulse and cloud the mind,

And leave me once again undone, possessed.

Think not for this, however, the poor treason

Of my stout blood against my staggering brain,

I shall remember you with love, or season

My scorn with pity, — let me make it plain:

I find this frenzy insufficient reason

For conversation when we meet again.

An Interesting Video Inspired by the Sonnet

Pingback: Edna St Vincent Millay & Trochaic Tetrameter « PoemShape

I have set this beautiful sonett to music, to a kind of progressive rock. If somebody is interested in poetry and music, you can visit my homepage and listen to the song (Song 15)

LikeLike

Thanks Dirk. You should supply a link if you would like readers to visit?

LikeLike

Pingback: Why Billy Collins and I Are Not on Speaking Terms Right Now | The Dad Poet

Pingback: Litlog | What Lips My Lips Have Kissed and Where and Why

Pingback: Happy Birthday, Edna St. Vincent Millay | The Dad Poet

Pingback: Why Billy Collins and I Are Not on Speaking Terms Right Now – David J. Bauman