So, last night I was contacted by a publicist hoping that I would interview an instragram poet by the name of Nicholas Denmon. I’m not familiar with Denmon’s efforts but am familiar with instapoetry and even bought Milk and Honey by Rupi Kaur. In case you’re not familiar with the term Instapoetry, it refers (if contemptuously in some circles) to free verse poems that are as little as two lines or as epic as twelve.

They have nothing to do with haiku and at worst are little more than declarative sentences. At right is one of Kaur’s better known examples and typifies the ‘form’, if it can be said to have one.

But what a kerfuffle I’ve missed these last six months. Turns out there are a number of poets and critics who have written some scathing reviews of Kaur’s poetry—and Instapoetry in general. Foremost among them, as far as I can gather, is , who wrote a fairly damning review in PN Review.

Momentarily setting aside Watts’s diatribe, I didn’t read Kaur’s book for its mastery of the arts of language and poetry. On that count, I think, a two or three line instaresumé would suffice. But she does have one skill set shared by other “masters”, and I use that term loosely, of the instapoem. Take the instapoem above. What’s clever about it is what makes it memorable. It’s a species of rhetoric, what’s called a figure of repetition. It’s an example of isocolon. Possibly also scesis onomaton and some other less pronouncable rhetorical figures I’m too rusty to recall. Isocolon is defined as “a rhetorical device that involves a succession of sentences, phrases, and clauses of grammatically equal length.” Strictly speaking, the two phrases aren’t of equal length, but close enough.

The most memorable lines in poetry, let alone Shakespeare, are commonly pristine examples of various rhetorical figures. Here’s Shakespeare’s use of isocolon from Sister Miram Joseph’s compendium Shakespeare’s Use of the Arts of Language:

“Your reasons at dinner have been sharp and sententious; pleasant without scurrility, witty without affectation, audacious without impudency, learned without opinion, and strange without heresy.” [p. 60]

You might also observe that Kaur’s verse is an example of grammatic parallelism, something which virtually defines Walt Whitman’s poetry. The point I’m making is that part of what makes Kaur’s verse memorable (along with good inspirational quotes and add copy) is her knack for rhetoric. This isn’t something to be lightly dismissed. While her  Instapoetry will never be confused with great literature, it’s worth trying to understand some of the elements that make it work and make it appealing. At left is another example.

Instapoetry will never be confused with great literature, it’s worth trying to understand some of the elements that make it work and make it appealing. At left is another example.

This instapoem pirouettes nicely, and meaningfully, on the pun of ‘spine’ (a pun is a rhetorical figure). While I’m in no way comparing Kaur to Shakespeare, this is the sort of game Shakespeare often played, and it works. Hence the appeal of Kaur’s poetry.

Instapoetry can be, to a degree, a rhetorician’s playground. The best examples, and the most memorable, I’m willing to bet, are those that skillfully, if unwittingly, make use of rhetorical figures, puns, figures of repetition, amplification, balance, antitheses, etc… Although I’m not going to exhaustively review Kaur’s poetry to prove or disprove my point, my hunch is that her own instapoetry, as compared to her peers, is the most skillful in that regard, and is amplified by subject matter that is, in fact, meaningful to a great many readers: immigration, domestic violence, sexual gratification along with sexual assault. Out of curiosity, I googled Tyler Knott Gregson’s favorite poems and landed here. Many of these poems contain examples of rhetorical figures found throughout poetry, though not as condensed as Kaur’s. All this is to say that when I read Rebecca Watts’s criticism of Instapoetry, I think her criticism of the verse form is rather shallow. I’m tempted to write more on that but a sufficiently thorough and effective response to Watts can be found here.

Among other criticisms, the most curious is the following:

“From literature we have hitherto expected better – not least because endurance, rather than fleetingness, is one marker of its quality. As Pound put it, literature is ‘news which stays news’. Of all the literary forms, we might have predicted that poetry had the best chance of escaping social media’s dumbing effect; its project, after all, has typically been to rid language of cliché. Yet in the redefinition of poetry as ‘short-form communication’ the floodgates have been opened. The reader is dead: long live consumer-driven content and the ‘instant gratification’ this affords”

This assertion deserves some skepticism. Above all, correlation does not equal causation. Just because these short verse forms coincide with social media’s ‘short-form communication’ doesn’t mean the former is a result of the latter. Are we to blame the entirety of Japanese literary tradition on the invention of the Internet?—the five line Tanka and the three line Haiku? But setting aside Japan, what about Martial’s epigrams? These are nothing if not instapoems.

The bee enclosed and through the amber shown

Seems buried in the juice which was his own.

Compare the following by Martial:

You never wrote a poem,

yet criticize mine?

Stop abusing me or write something fine

of your own!

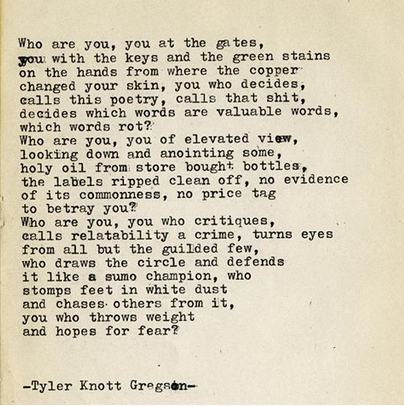

To the much wordier Tyler Knott Gregson:

And Ben Jonson also took up Epigrams. Was this turn to short-form communication also a result of social media?

XXXIV Of Death

He that fears death, or mournes it, in the just,

Shewes of the resurrection little trust.

[The Complete Poetry of Ben Jonson, p. 16]

Compared to Rupi Kaur:

“when death

takes my hand

i will hold you with the other

and promise to find you

in every lifetime”

So, apart from its name, I’d argue that instapoetry isn’t anything literature hasn’t seen before. Despite Watts’s criticism of instapoetry as “artless” — “The short answer is that artless poetry sells.”— Kaur’s verse is firmly within the century-long aesthetic manifesto of free verse. The instapoem by Ben Jonson is metrical and rhymes. The instapoem by Kaur is free verse. If artlessness is a lack of metaphor, figurative language, meter (let’s say), rhyme, or any of the “Arts of Language” associated with poetry prior to Ezra Pound, then artlessness equally applies to the entirety of the free verse project. There’s really little difference, at all, between a poem by Tyler Gregson and one by W.S. Merwin. Merwin, of all poets, anticipates the “artlessness” of instapoetry (if it’s to be labeled “artless”). To be blunt, there’s not a single criticism that Watts levels at instapoetry that can’t also be leveled at Watts’s own poetry (let alone the poems in the same publication, in the selfsame issue, that printed her critique). Not one. To whit: A poem of hers, Turning, published at The Guardian begins:

Now it’s autumn

and another year in which I could leave you

is a slowly sinking ship.

The first stanza is a declarative statement ending with a clichéd metaphor. In isolation, its virtually indistinguishable from any number of Kaur’s instapoems. That said, here’s a poem by Kaur:

i know i

should crumble

for better reasons

but have you seen

that boy

he brings

the sun to

its knees

every night

Kaur’s passage, “brings the sun to its knees”, is a much more original and powerful metaphor than Watts’s trite “sinking ship”. Watts does better, though, as her poem goes on. She makes an effort: “The air has developed edges”; “…the brazen meadow no longer/ presumes to press its face to the window/ like an inquisitor.”; “even the river will evince a thicker skin”; “…my breath each morning will flower white…”; “all of summer’s schemes will fly like cuckoos”; “Bonfire smoke/ between us like a promise lingers.”

How do instapoets compare? Watts personifies the “brazen” meadow (as an inquisitor via a simile) that presses its face to the window—an example of prosopopoeia. This isn’t bad, as far as things go, but the simile “like an inquisitor” gilds the lily. Compare this to an instapoem by K. Towne Junior:

sometimes a heart must be

broken to slip through the bars of

its cage

K. Towne Jr’s prosopopoeia is nearly identical to Watts. The only difference is that K. Towne Jr possessed the wisdom not to add the extenuating simile, like a prisoner. Watts writes that “even the river will evince a thicker skin”. This and the metaphorical “the air has developed edges” and “my breath…will flower white” are, I think (again, being a little rusty), examples of catachresis. A good definition of catachresis comes from here:

Catachresis is a figure of speech in which writers use mixed metaphors in an inappropriate way, to create rhetorical effect. Often, it is used intentionally to create a unique expression. Catachresis is also known as an exaggerated comparison between two ideas or objects.

Do instapoets use mixed metaphors like catechresis? Here’s Tyler Gregson, even using the same imagery, combining catachresis and prosopopoeia:

The parallels aren’t exact but close enough to say that Watts doesn’t do anything, as far as the “art” of poetry goes, that instapoets like Gregson and Kaur don’t. So either their verse is as artful as hers, or hers is as artless as theirs. And that begs the question, if artless poetry sells, why is contemporary poetry in such a miserable state? As it happens, a number of observers ascribe the criticism to nothing more than envy and resentment. How is it that an MFA graduate, having spent thousands to obtain a degree in the “art of poetry”, molders in the obscurity of barely read poetry journals while an artless versifier like Rupi Kaur, never published in an important journal and lacking the grateful connections afforded by academia, amasses a following of tens of thousands and sells over a million copies of her book? She hasn’t even been published <gasp> in the American Poetry Review! How is it that that once living synechdoche of everything the late 20th century poetry establishment stood for, the inscrutable John Ashbery, is already fading <understatement> into the obscurity of two (2) reviews at Amazon while rupi kaur’s Milk and Honey has already garnered five thousand eight hundred and eighty (5,880)? The establishment poets of the last 50 years are left like Anthony whistling i’th’marketplace, while the crowds run off to gawk at rupi’s riggish Cleopatra. And rather than give them pause, they have drawn the only possible conclusion: It must be because their poetry is so artful whilst the poems of the instapoets are so artless.

Ask me and I would say that the free verse manifesto of the last hundred years has become the serpent biting its own tale. Poets can’t declare, as England’s Poetry Society did, that:

“There is poetry in everything we say or do, and if something is presented to me as a poem by its creator, or by an observer, I accept that something as a poem.”

Then point a trembling finger at instapoets proclaiming that their verses are not poems and their authors are not poets. But, to the embarrassment of pots and kettles everywhere, they do.

My own opinion of instapoetry is that of amusement. It does take a certain kind of talent to write them—though maybe not poetic talent. I have a collection of books that I love, all of them collected proverbs. In Vermont, for example, we might say of some: He’s so crooked, he could hide behind a corkscrew. If we’re impatient: He’s slow as a hog on ice with its tail froze in. In my dictionary of American proverbs: A Wolf may change his mind but never his fur. Another proverb (worthy of Kaur): A friend by your side can keep you warmer than the richest fur. If you’re feeling put upon: The mills of the gods grind slowly, but they grind exceedingly fine. Two other books I have: Shakespeare’s proverb lore, because Shakespeare loved proverbs and sprinkled hundreds throughout his plays (many of Shakespeare’s most famous lines are actually inspired by proverbs), and another is of English proverbs prior to 1500: Leave not an old friend for new. Prior to 1500 we might say: The habit does not make the monk. Nowadays we say: He’s all hat and no cattle.

My observation is that the best instapoets are not writing poems. They’re writing proverbs. Poets who criticize and satirize them, I think, misunderstand the nature of what writers like Kaur do and the reasons they’re so beloved. It’s not clear that Kaur herself understands but she clearly has a genius for proverbs. (Poetry and proverbs are kissing cousins.) And you can trace that genius in other poets and writers. Kahlil Gibran, who Kaur reminds me of, was beloved by readers, considered a poet, and was a wellspring of proverbs:

“You were born together, and together you shall be forevermore but let there be spaces in your togetherness. And let the winds of heaven dance between you.”

Visiting a Pinterest site I came across this instapoem which, again, is really a proverb (and worth waking up to every morning):

We are all bad in someone’s story.

But if all this isn’t enough to mollify the critics of instapoetry, then the best I can do is to paraphrase one of Rupi Kaur’s poems:

the world

gives her

so much pain

but here she is

making gold out of it

La!

- For another and more recent post on the topic of Kauer and Instapoetry: The Search for Meaning in a New Generation of Poets & Readers

A fascinating and interesting take on the whole debacle. Most treatments I have read have been shamefully snobbish with little of substance.

Incidentally, this fervor for the bon mot is entirely recognisable to Classicists given the prevalence of rhetorical sententiae throughout antiquity. They often made good use of rhetorical figures and their pithiness allowed them to spread far beyond the type of complicated poetry favoured by the elite.

LikeLike

Agree with your observation concerning classicists. During the Elizabethan era, you know, they used to collect sententiae like these straight from the source, whether they were poems, novels or plays, like little shiny coins. I think it reached a fevered pitch with John Lyly and Euphues. Although, in those days, I’m not sure there was such a thing as “the elite”. That crew, I think, showed up later with the Restoration.

LikeLike

Interesting. There used to be a specific Latin name for those sort of books I believe, a delectus? At least that is the name given to those I have seen collecting Latin/Greek illustrations of grammatical points.

LikeLike

Yeah, that’s above my pay grade. I’ve been reading some posts from your blog, and I’ll take your word for it. The next time I have questions about classical poetry and/or literature, I’m coming to you. One being, have there been any newsworthy findings out of Oxyrhynchus, Egypt, lately?

Also, I prefer the Odyssey to the Illiad. I just find the latter too grindingly unrelenting in its depiction of war.

LikeLike

i love this! how you break it down this was a really good read.

LikeLike

Thanks. :) Glad you liked it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: The search for meaning in a new generation of Poets & Readers « PoemShape

Reblogged this on Let's Talk About It.

LikeLike

This topic reaches far beyond sentence structure, for we are constantly evolving. Now with evolution one must expect change because without it we are doomed. Expect to see animation and short film. You heard it from the source. I am Jefferson Curio, and I’m the author of the PHENOMENAL work The Gift, and recently Celebrity Crush.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey Wilbert, cleaned up your sentence structure just a little. The topic might be far beyond sentence structure, but English isn’t, and you’re still gonna’ need it. :)

LikeLike

Pingback: Why I’m an idiot « PoemShape

Pingback: Who loses and who wins; who’s in, who’s out- « PoemShape

Pingback: Who loses and who wins; who’s in, who’s out- « PoemShape - اردو میں خبریں