- Sept 22, 2009 • Just learned that Jane Campion has made a movie “based” on the relationship between John Keats and Fanny Brawne. You can watch the trailer at the bottom of the post.

About the Poem

I have two luxuries to brood over in my walks, your loveliness and the hour of my death. O that I could have possession of them both in the same minute. – John Keats in a letter to Fanny Brawne

Bright Star is one of Keats’s earlier poems and I can’t help but detect the opening of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 116.

Let me not to the marriage of true minds

Admit impediments. Love is not love

Which alters when it alteration finds,

Or bends with the remover to remove:

O no! it is an ever-fixed mark

That looks on tempests and is never shaken;

It is the star to every wandering bark,

Whose worth’s unknown, although his height be taken.

Shakespeare equates love to a star and this association was surely present in Keats’ mind from the time he first read Shakespeare’s Sonnet. That is, the star isn’t only a symbol of steadfastness and stability, but also love. And love, in Keats’s mind, is unchangeable and ever-fixèd (or else it isn’t love). Shakespeare’s Ever-fixèd turns into Keats’ steadfast. Shakespeare’s never shaken turns into Keats’s hung aloft the night and unchangeable. R.S. White, in his book Keats as a reader of Shakespeare, makes note of some other parallels as well:

…it is not possible to ignore a creative connection between Keats’s resonant line, “Bright Star, would I were stedfast as thou art–‘ and on the one hand the phrase of the undoubtedly ‘stedfast’ character, Helena,

‘Twere all one,

That I should love a bright particular star, (I.i.79-80)and on the other, although the play is not marked, Julius Ceasar’s more ironic ‘But I am constant as the northern star’ (Julius Ceasar, III.i.60). Such echoes, whether intende, unconcious or even coincidental, display vividly the special compatibility between the language and thought of Keats and the parts of Shakespeare which he appreciated and assimilated so thoroughly. [p. 72]

White’s survey of Keats’ Shakespearean influence isn’t just guess work by the way. Keats’ copy of Shakespeare’s plays is still extent, along with his comments, underlinings and double-underlinings. White’s book is an interesting commentary on Keats’ reading of Shakespeare. White observes another interesting parallel between Shakespeare and Keats’ poetic thought:

[Keats] picks out one of the images in the [Midsummer Night’s Dream] to convey his enthusiasm for Shakespeare’s poetry of the sea, which he often equates with Shakespeare himself:

Which is the best of Shakespeare’s Plays? – I mean in what mood and with what accompaniment do you like the Sea best? It is very fine in the morning when the Sun

‘opening on Neptune with fair blessed beams

Turns into yellow gold his salt sea streams’Keats seems to be trusting his memory for the quotation, for his ‘salt sea’ is actually ‘salt green (II.ii.329-3). By associating Shakespeare himself with the moods of the sea, Keats is perhaps conveying something of his notion of the dramatist’s developement, implying that after the morning of this play the sea will become rougher as the day goes on. Shakespeare’s sea-music informs Keats’s poetry as well, particularly in the sonnets ‘On the Sea’ and ‘Bright Star’. [p. 102]

What White doesn’t mention are the parallels between Keats’ Sonnet and Shakespeare’s. Notice how the sea makes it’s appearance in both sonnets.

…it is an ever-fixed mark

That looks on tempests and is never shaken;

It is the star to every wandering bark…

Compared to Keats

…watching, with eternal lids apart,

Like nature’s patient, sleepless Eremite,

The moving waters at their priestlike task

Of pure ablution round earth’s human shores…

And there are also some parallels in Keats’ letters that remind one of the Sonnet’s central themes.  The most explicit, in terms of thematic content, comes from May 3, 1818, in a letter to his fiance Fanny Brawne.

The most explicit, in terms of thematic content, comes from May 3, 1818, in a letter to his fiance Fanny Brawne.

“. . .I love you; all I can bring you is a swooning admiration of your Beauty. . . . You absorb me in spite of myself–you alone: for I look not forward with any pleasure to what is call’d being settled in the world; I tremble at domestic cares–yet for you I would meet them, though if it would leave you the happier I would rather die than do so. I have two luxuries to brood over in my walks, your Loveliness and the hour of my death. O that I could have possession of them both in the same minute. I hate the world: it batters too much the wings of my self-will, and would I could take a sweet poison from your lips to send me out of it. From no others would I take it. I am indeed astonish’d to find myself so careless of all charms but yours–remembering as I do the time when even a bit of ribband was a matter of interest with me. What softer words can I find for you after this–what it is I will not read. Nor will I say more here, but in a Postscript answer any thing else you may have mentioned in your Letter in so many words–for I am distracted with a thousand thoughts. I will imagine you Venus tonight and pray, pray, pray to your star like a Hethen.”

Love letters don’t get much better than this and Keats’ Sonnet is thought to be a love poem to Fanny Brawne – and  Brawne herself treated it as such. She copied Bright Star into her “very dear gift” of Dante’s Inferno – along with its thematically related (but much less successful) companion sonnnet As Hermes once took his feathers light (see below). Anyway, worth noting is his comparison of Brawne to a star and his desire, as in the poem, to “swoon to death” or, as he puts it – “I could take a sweet poison from your lips to send me out of it.” The play of death and orgasm shouldn’t be overlooked in all this romantic swooning. The conceit is probably as old as sex and, Keats, if nothing else, was an über sensualist. If tuberculosis hand’t killed him, sex probably would have.

Brawne herself treated it as such. She copied Bright Star into her “very dear gift” of Dante’s Inferno – along with its thematically related (but much less successful) companion sonnnet As Hermes once took his feathers light (see below). Anyway, worth noting is his comparison of Brawne to a star and his desire, as in the poem, to “swoon to death” or, as he puts it – “I could take a sweet poison from your lips to send me out of it.” The play of death and orgasm shouldn’t be overlooked in all this romantic swooning. The conceit is probably as old as sex and, Keats, if nothing else, was an über sensualist. If tuberculosis hand’t killed him, sex probably would have.

There are still some more interesting parallels. Amy Lowell, in her biography on Keats called John Keats, argues that during a visit to a Mrs. Bentley’s, Keats writes to George (his brother) that he ” put all the letters to and from you and poor Tom and me…” [Book II, p. 202] In one of these letters, which Lowell argues Keats must have reread, comes the following:

“We are now about seven miles from Rydale, and expect to see [Wordsworth] to-morrow. You shall hear all about our visit .

There are many disfigurements to this Lake — not in the way of land or Water. No; the two views we have had of it are of the most noble tenderness – they can never fade away – they make one forget the divisions of life; age, youth, poverty and riches; and refine one’s sensual vision into a sort of north star which can never cease to be open lidded and stedfast over the wonders of the great Power…” [Book II, p. 22]

As Lowell points out, the parallels are too uncanny. It doesn’t take much to go from, a sort of north star which can never cease to be open lidded and stedfast over the wonders of the great Power, to:

Not in lone splendour hung aloft the night

And watching, with eternal lids apart,

Like nature’s patient, sleepless Eremite,

Bright star, would I were stedfast as thou art–

If Keats didn’t lift from having re-read an older letter, then the imagery linking the open lidded eye with the North Star, the one constant star of the sky, was certainly ever fixed in his mind. All poets, and this is something I would like to write more about, reveal a habit of thought, imagery and associations over the course of their careers. The great poets vary them, the competent poets don’t.

Yet another anecdote is related by another of Keats’s biographers, Aileen Ward. She notes that while writing a letter, Keats saw Venus rising outside his window. Ward says that at that moment all “doubt and distraction left him; it was only beauty, Fanny’s and the star’s, that mattered.”

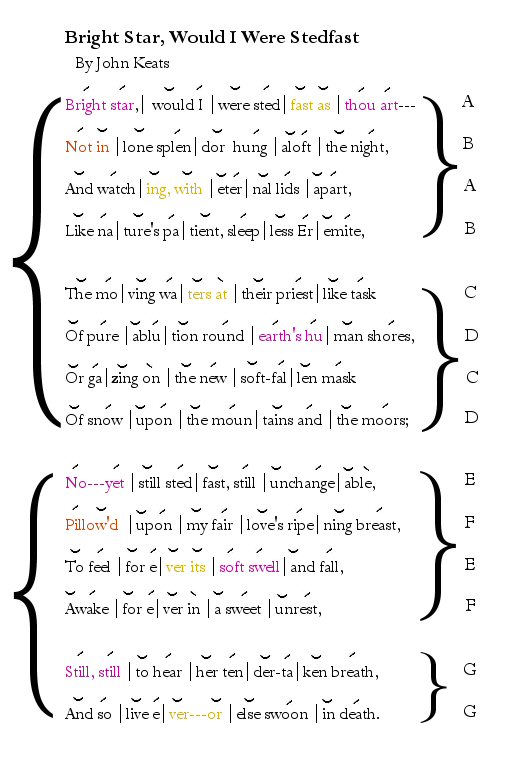

The Sonnet and its Scansion

- Note! I notice that many internet versions of this poem (including the video below) have “To feel for ever its soft fall and swell,” instead of “To feel for ever its soft swell and fall“. This may be a viral mistake. One text was typed incorrectly and everyone else copied and pasted. On the other hand, I notice that a copy in The Oxford Book of Sonnets prints the former version. The version I use is from Jack Stillinger’s the Poems of John Keats, considered to be the most accurate textually. He states that his text is “from the extant holograph fair copy” [p. 327]. I put my money on Stillinger. However, there are metrical reasons why I consider Stillinger’s to be correct. More detail on that below.

The first thing to notice about the sonnet is that it’s a Shakespearean Sonnet. If you’re not sure what that entails then follow the link and you will find my post on Shakespearean, Petrarchan and Spenserian Sonnets. Also, if you’re not sure about scansion or how it’s done, take a look at my post on The Basics. Keats wrote Sonnets in a variety of forms. That he chose the Shakespearean Sonnet, I think, is telling. With all the other parallels, why not the structure of the sonnet?

The form allows Keats to gradually build the the sonnet toward the epigrammatic climax of the couplet:

Still, still to hear her tender-taken breath,

And so live ever–or else swoon to death.

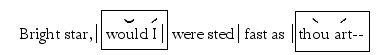

The second thing to notice is the meter itself. The first line of the first quatrain is, perhaps, the most easily misread, like Shakespeare’s Sonnet 116 or Donne’s Death Be Not Proud. We live in an age when Meter has become a art for fringe poets. As a result, many, if not most, modern poets and readers misread metrical poetry for lack of experience and knowledge. Most modern readers would probably read the line as follows:

Bright star, would I were stedfast as thou art–

This makes a hash of the meter, effectively reading the line as though it were free verse. But Keats was writing in a strong metrical tradition. As I’ve said in other posts, if one can read a foot as Iambic, then one probably should. So instead of reading the line like this:

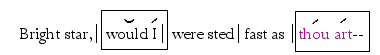

We should probably read it like this:

Or we should read the final foot as an outright spondee (as I originally scanned it):

Fortunately, unlike my fruitless search for a good reading of Donne’s sonnet, I found a top notch reading of the poem on Youtube. Here it is:

To my ears, he reads the last foot as a spondee. None of these alternate last feet are iambs, by the way. When I say that a foot should be read as an Iamb if it can be, I mean that a foot should be read with a strong stress on the second syllable (an Iamb or Spondee), rather than a falling stress (a trochee). The other reason for emphasizing art is that it’s meant to rhyme with apart. If one de-emphasizises art with a trochaic reading, then we end up with a false rhyme. Two nearly unpardonable sins would have been committed by the standards of the day. A trochaic final foot in an Iambic Pentameter pattern (unheard of) and an amateurish false rhyme. Keats was aiming for greatness. We can be fairly sure that he didn’t intend a trochaic final foot.

Bright star, would I were stedfast as thou art–

Not in lone splendour hung aloft the night

And watching, with eternal lids apart,

Like nature’s patient, sleepless Eremite…

Other than that, the first quatrain is fairly straightforward. An eremite is a hermit. So, what Keats is saying works on two levels. He wants to be steadfast (and by implication her as well), like the North Star (Bright Star), but not in lone splendor – not in lonely contemplation. Keats isn’t wishing for the hermit’s patient search for enlightenment. Nor, importantly, is he wishing for the hermit’s asceticism – his denial of passion and earthly attachment – in a word, sex.

The moving waters at their priestlike task

Of pure ablution round earth’s human shores,

Or gazing on the new soft-fallen mask

Of snow upon the mountains and the moors;

In the second quatrain Keats describes the star’s detachment, like the hermit’s, as one of unmoving observation and detachment. The star’s sleeplessness is beautiful and it’s contemplation holy – observing the water’s “priestlike task of pure ablution”. But such contemplation is, for Keats, an inhuman one. It’s no mistake that Keats refers to the shore’s as earth’s human shores – a place of impermanence, fault and failings in need of “pure ablution”. This the world the Keats inhabits. Up to this point, all of Keats’s imagery is observational. The only hint of something more is in the tactile “soft-fallen”. There is little sensual contact or life in these images; but the first two quatrains present a kind of still life – unchanging, holy, and permanent. That said, there’s the feeling that the “new soft-fallen mask/ Of snow upon the mountains” anticipates his lover’s breasts.

The Volta

The sonnet now turns to toward life and, ironically, impermanence. Notice the nice metrical effect of spondaic first foot, it’s emphasis on the word No. One can produce a similar effect in free verse, but the abrupt reversal of the meter, also signaling the Sonnet’s volta, is unmatchable.

No–yet still stedfast, still unchangeable,

Pillow’d upon my fair love’s ripening breast,

To feel for ever its soft swell and fall,

Awake for ever in a sweet unrest,

Notice how the imagery changes. We are suddenly in a world of motion, touch, and feeling. No, says Keats, he wants the permanence of the star but also earth’s human shores. He wants to be forever “pillow’d upon [his] fair love’s ripening breast”. The anthimeria of pillow, using a noun as verb, sensually implies the softness and warmth of Fanny Brawne’s breasts. The next line gives life and breath to his imagery: He wants to feel her breasts “soft swell and fall” forever “in a sweet unrest”. The sonnet’s meter adds to the effect – the spondaic soft swell follows nicely on the phyrric foot that precedes it, reproducing, it its way, the rise and fall of her breasts. (Also, it’s worth noting that metrically, it makes more sense to have soft swell be a spondaic foot, rather than (as with some versions of the poem) soft fall. The meter, in a sense, swells with the intake of Fanny’s breath. ) Anyway, on earth’s human shores, there is nothing that is unchangeable and immutable. And Keats knows it. The irony of Keats’ desire for the immutable in a mutable world must find resolution – and there is only one:

Still, still to hear her tender-taken breath,

And so live ever–or else swoon to death.

If he could, he would live ever so, but Keats knows the other resolution, the only resolution, must be death.  Immutability, permanence and the unchangeable can only be found in death.

Immutability, permanence and the unchangeable can only be found in death.

But what a way to die…

And this brings us to the erotic subtext of the poem. As I wrote earlier, the idea of orgasm, which the French nicely call the little death or la petite mort, is an ancient conceit (the photo at right, by the way, is called La petite mort, clicking on the image will take you to Kirilloff’s gallery). If we read Keats’ final words as a wry reference to the surrender of orgasm, then there’s a mischievous and wry smile in Keats’ final words. After all, how do readers interpret “swoon“? Webster’s tells us that to swoon is “to enter a state of hysterical rapture or ecstasy…” Hmmm…. It’s hard to know whether Keats had this in mind. He never wrote overtly sexual poetry, but there is frequently a strong erotic undercurrent to much of his poetry. He was, after all, a sensualist. (Many of the poets who came after him accused him of being an “unmanly” poet – of being too sensuous and effeminate. Keats’ eroticism runs more along the lines of what is considered a feminine sensuality of touch and feeling.)

Such overt suggestiveness might be a little out of character for Keats but, if it was intended, I think it adds a nice denouement to the sonnet. After all, what is a lust and passion but a “sweet unrest”? And what is the only release from that “sweet unrest” but a swoon to death? But in this “death”, life is renewed. Life is engendered, remade and made immutable through the lovers’ swoon or surrender to “death”. Keat’s paradoxical desire for the immutable is resolved. The pleasure of the mutable but sweet unrest of his lovers rising and falling breasts, is only mitigated by the even more pleasurable, eternizing and transcendent pleasure of “death’s swoon”.

Which does Keats prefer? The immutable pleasure implied by the analogy of the changeless star, or the swoon of death? Keats, perhaps, is ready to find pleasure in both. The sonnet is profoundly romantic but, in keeping with Keats’ character, wryly pragmatic.

But this interpretation is conjectural. To Amy Lowell, the final lines are characterized as ending in a “forlorn, majestic peace” and I think this is how the majority of readers read the poem. I, personally, can’t help but think that there was more to Keats’ desire than Romantic obsession. The sheer, physical sexuality of resting his cheek on his lover’s breasts is more than just Romantic boiler plate.

The First Version

And here’s something won’t see very often on the web – considered to be Keats’ first version of the Sonnet.

Bright star, would I were stedfast as thou art–

Not in lone splendour hung amid the night

And watching, with eternal lids apart,

Like nature’s devout, sleepless Eremite,

The morning waters at their priestlike task

Of pure ablution round earth’s human shores,

Or gazing on the new soft-fallen masque

Of snow upon the mountains and the moors–

No–yet still stedfast, still unchangeable,

Cheek-pillow’d on my Love’s white ripening breast,

Touch for ever, its warm sink and swell,

Awake for ever in a sweet unrest,

To hear, to feel her tender-taken breath,

Half passionless, and so swoon on to death.

To students of poetry, what is worth noting is how few changes made a moving but flawed sonnet into a work of genius. As I’ve said before , it’s not the content of poetry that makes it great, but the style – the language. The first version, in terms of content, is ostensibly the same as the second version.

- Changing amid to aloft gives the feeling of a star that is apart from the others, aloft, rather than amid.

- The adjective devout is simply descriptive – having little connotative power. But the adjective patience is attributive and gives the description the force of personality. It also plays against Keats’ sweet unrest, later in the sonnet. Patience, Keats tells us, is not an attribute he wants to mimic, only its steadfastness and unchangeableness.

- The change of morning to moving, again changes a simply descriptive adjective to an attributive adjective. Moving gives the waters motion and a kind of intent. It also avoids the conflict of the star having been hung aloft the night, but watching the morning waters.

- Keats’ initial choice of masque is curious and may be a misprint. A masque is a short, usually celebratory, one act play.

- “Cheek-pillow’d on my Love’s white ripening breast,” gives us more information than we need. We can already guess that it’s his cheek on her breasts because he uses the anthemeria pillow’d. What else do we put on our pillows but our cheeks? Her white breast is unnecessary. All but a handful of 19th Century English women had white breasts. Keats was just trying to fill out the meter with the adjective white. “Pillow’d upon my fair love’s ripening breast,” dispenses with both of the former redundancies. The word fair is there solely for the sake of the meter, but doesn’t feel as extraneous or contrived as white. It also allows the emphasis to turn to ripening, which is a beautifully erotic description of a young woman’s breast.

- “Touch for ever, its warm sink and swell,” The verb touch lacks the rich connotation of feel. After all, we might forensically touch a hot kettle, to find out if it’s too hot; but we wouldn’t feel it. Feeling things is a tactile, sensual act when we want to explore an object. Warm sink and swell is replaced by soft swell and fall. Once again, the adjective warm lacks the connotative sensation of soft. To know that something is warm, we don’t necessarily need to touch or feel it. But to know something is soft implies a more tactile and sensual exploration. The verb sink is a less neutral expression than fall. Boats sink. Rocks sink. Drowning swimmers sink. Most importantly, when objects sink, they tend not to rise again. Fall is a more neutral, less loaded description. It also rhymes better with unchangea(ble). Keats may have been uneasy with the rhyme between (ble) and swell.

- To hear, to feel is replaced by Still, still to hear. The latter phrase gives the final couplet a more dramatic, less literary feel. We can hear the wistfulness and expectation of an actual speaker in the disrupted meter – the epizeuxis of Still, still…

- The final line is the most dramatic alteration: “Half passionless, and so swoon on to death.” Half passionless undercuts the eroticism of the poem. Who is half-passionless? Keats? Brawne? What does that mean? The closing line appears to give the sonnet’s ending a more despondent tone, conflicting with the idea of a sweet unrest. Keats probably meant to imply that his ardor was both like the star’s, detached, and like attachment of a lover. But I suspect he sensed the contradiction in the description. It undercuts what had, until then, been a profoundly passionate poem. It also undercuts the erotic suggestiveness of a swooning death.

And here is the companion Sonnet Fanny Brawne wrote into her copy of Dante:

As Hermes once took to his feathers light,

When lulled Argus, baffled, swooned and slept,

So on a Delphic reed, my idle spright

So played, so charmed, so conquered, so bereft

The dragon-world of all its hundred eyes;

And seeing it asleep, so fled away,

Not to pure Ida with its snow-cold skies,

Nor unto Tempe, where Jove grieved a day;

But to that second circle of sad Hell,

Where in the gust, the whirlwind, and the flaw

Of rain and hail-stones, lovers need not tell

Their sorrows. Pale were the sweet lips I saw,

Pale were the lips I kissed, and fair the form

I floated with, about that melancholy storm.

If this post was enjoyable or a help to you, please let me know! If you have questions, comments or suggestions. Comment. In the meantime, write (G)reatly!

Bright Star by Jane Campion

Don’t know much about the movie. But as with all movies like these, it may be based on a true story, but it remains a work of fiction. I can’t wait to see it.

Terrific commentary. By the way,

‘opening on Neptune with fair blessed beams

Turns into yellow gold his salt sea streams’

is also echoed in the Nightingale Ode–I think it goes:

Charmed magic casements opening on the foam

Of perilous seas in faerie lands forlorn.

Fred Turner

LikeLike

Thanks Frederick. Nice to see you here. I failed to mention (something White himself mentions) that Keats’s memory of the line was wrong. It should have read “salt green streams”.

LikeLike

Another wonderful post! I learn so much from each one I read from you and each time it makes me more excited to continue to read poetry.

I also enjoyed Fanny’s poem – I would be curious to hear what you think of its aesthetic merits (I have to admit that it makes me a little sad to think that all the great Romantic era poets were male, and that Mary Shelley’s only well-known work is Frankenstein…)

LikeLike

Oops… I must have given the impression that the second sonnet was Fanny’s! It was also Keats’s Sonnet. Fanny didn’t write any poetry. However, a female poet who may have influenced Keats was Mary Tighe. (I think I spelled her name correctly.) She was very, very popular in her own day, and widely read.

EB Browning wrote some great poetry.

Christina Rosetti still sells better than many modern free verse poets.

But you’re right, there aren’t any female poets who we’d rank alongside Keats. I don’t know why. Interestingly though, there were many female poets who were widely known and read in their own day. I don’t know if that bodes well for female poets today, but we’ll see. The vast majority of poets, men and women, are forgotten.

LikeLike

“There aren’t any female poets who we’d rank alongside Keats”? Well, we all have different taste. Personally I think Emily Dickinson is a greater poet than Keats. I wore out my copy of Thomas H. Johnson’s edition.

LikeLike

Thanks Jay. I’m glad that you write that; and I’m sure you’re not alone. We do all have different tastes, but my comment referred more to the critical consensus. Perhaps I should have written “critical consensus” rather than “we”. In truth, comparing poets like Keats and Dickinson is fraught with objections – a bit like comparing Beethoven and Chopin. They were doing two different things. I don’t view Chopin as being as great a composer as Beethoven for similar reasons that I don’t view Dickinson as great as Keats, but I can’t imagine music without the genius of Chopin anymore than poetry without the genius of Dickinson.

LikeLike

Jackie,

Just came back from work. Take a look here. I actually own this book. You can get your own copy for 48 Cents. Buy a copy. Tell me what you think.

LikeLike

Thank you! I love finding those great deals on Amazon… I am very excited for the Summer because as much as I love reading literature, I love much more spending my own time with it and not trying to race along with a syllabus… I will definitely take a look at that anthology then.

LikeLike

Jackie, here’s another good anthology. Not as cheap as the Victorian Women’s Anthology, but I actually think the poetry is better – fresher. Nineteenth Century American Women Poets. Right now, you can get it used for about $15.

LikeLike

How I love Keats! I fell in love with “To Autumn” in highschool, although living as I was in Geneva, it’s hardly surprising I was turning Romantic. I finished reading your history of Iambic Pent, and it was pretty sturdy stuff (much in line with the tone of Fussell’s _Poetic Metre & Poetic Form_ which I finished this week), and it is refreshing to find other poets so passionate in the cause of tradition. I do intend to read as much of this site as I can manage, but I have one tiny request: would you mind taking down that nude photograph? My Muslims eyes are forbidden even to gaze at a head of feminine hair, let alone.. other.. more.. distracting.. objects.

Rafael

University of Miami

LikeLike

Hello Rafael. I won’t remove the nude photograph because I’m not Muslim and because I consider the beauty and enjoyment of nudity, a man or woman’s, a divine gift and one of life’s great pleasures – it is, after all, what Keats was writing about. Beauty is truth, truth is beauty. Asking me to remove the photo is asking me to violate my own beliefs.

However, you have other options. Consider downloading a text-only browser. There’s lynx, but I don’t recommend it unless you’re computer savvy. The easiest thing to do is to block all images in Firefox. You can even specify websites, like mine, with images that offend you.

LikeLike

I agree with you that it is a divine gift, I just feel it should be a private one too. Anyway, thanks for the consideration.

LikeLike

You’re welcome. It must be difficult, at times, to live in a culture like ours. Be well.

LikeLike

Thank you for your informative commentary. I really enjoyed it. You helped me understand the poem. I am assisting my son with his assisgnment and have been searching different sites to help me answer the work sheet we have. Your commentary was very interesting. Unfortunately, I was unfamiliar with the poem and have found it difficult to answer these questions. Thank you again!

LikeLike

Thanks Marina. Comments like yours make my day. :-)

LikeLike

Thank you for responding! I have a question perhaps you could help me answer on this assisignment. We have been answering the S.O.A.P.S.tone of the poem Bright Star and thanks to your commentary I have been able to answer all of the letters but the last”S” , speaker. (I never even heard of S.O.A.P.S.tone before my son brought this assisgnment home). You really helped me understand it. Whew! Question: When they ask the “S” for speaker do they mean the tone of the poem or what exactly? I would appreciate it if you could make this clear for me. Thank you for your time and attention to this question.

Marina:)

LikeLike

OK, here’s what I’ve got for SOAPS Tone analysis (from a PDF).

• • •

S.O.A.P.S. Tone Document Analysis

The SOAPS Tone Document Analysis allows students to trace an examination of a document

using the seven components listed. This approach to analysis is relevantly used in poetry,

speeches, short stories, newspaper articles, and countless other documents. Oftentimes, this

approach is introduced to AP students at the high school level. However, in this case, this

approach is used my classroom on all levels to stimulate and “prove” student’s point in analyzing

particular documents. Remember, all components of this approach MUST be supported from the

text and MUST be backed up by the words from the text.

Speaker

Who is the speaker who produced this piece? What is the their background and why are they

making the points they are making? Is there a bias in what was written? You must be able to cite

evidence from the text that supports your answer. No independent research is allowed on the

speaker. You must “prove” your answer based on the text.

Occasion

What is the Occasion? In other words, the time and place of the piece. What promoted the author

to write this piece? How do you know from the text? What event led to its publication or

development? It is particularly important that students understand the context that encouraged

the writing to happen.

Audience

Who is the Audience? This refers to the group of readers to whom this piece is directed. The

audience may be one person, a small group or a large group; it may be a certain person or a

certain people. What assumptions can you make about the audience? Is it mixed racial/sex

group? What social class? What political party? Who was the document created for and how do

you know? Are there any words or phrases that are unusual or different? Does the speaker use

language the specific for a unique audience? Does the speaker evoke God? Nation? Liberty?

History? Hell? How do you know? Why is the speaker using this type of language?

Purpose

What is the purpose? Meaning, the reason behind the text. In what ways does he convey this

message? How would you perceive the speaker giving this speech? What is the document

saying? What is the emotional state of the speaker? How is the speaker trying to spark a reaction

in the audience? What words or phrases show the speaker’s tone? How is the document supposed

to make you feel? This helps you examine the argument or it’s logic.

Subject

What is the subject of the document? The general topic, content, and ideas contained in the text.

How do you know this? How has the subject been selected and presented? And presented by the

author?

Tone

What is the attitude of the speaker based on the text? What is the attitude a writer takes towards

this subject or character: is it serious, humorous, sarcastic, ironic, satirical, tongue-in-cheek,

solemn, objective. How do you know? Where in the text does it support your answer?

• • •

According to this, the last S is Subject, but anyway…

Here are the questions:

Who is the speaker who produced this piece? Is this case it would be Keats, although I wonder if it could also refer to the persona the poet assumes. One can never assume that the poet is speaking strictly as himself. By the very act of writing poetry, the poet is also assuming a role. In the case of Keats’ poem, he’s writing a Shakespearean Sonnet. Sonnets generally typified the genre of love and courtship. Keats was expressing his role as a suitor and lover.

What is the their background and why are they making the points they are making? This is a curious question and, in a certain way, who cares? Is it necessary to know the poet’s background in order to read, understand or interpret his poem? In my view a poet has failed (somewhat) if it’s necessary to know their background. But anyway, Keats’ background is his love for Shakespeare and Milton. Specifically, he was a reader of Shakespeare and he drew on Shakespeare’s imagery (in part) to express his own yearning. What point is he making? That he would seduce her with the beauty of his language. His love for her is expressible in his poetry and, remember, it was Keats who famously said the truth is beauty and beauty is truth. In this light, the beauty of his poetry is also expressive of his love’s truthfulness.

Is there a bias in what was written? There is a sense of humor which, in itself, might be considered bias.

You must be able to cite evidence from the text that supports your answer. No independent research is allowed on the speaker. You must “prove” your answer based on the text.

That’s sensible… sort of. I can’t see, however, how one is supposed to consider the “speaker’s” background without some “independent research”. If research is disallowed, then it’s not facts they’re looking for, but the fictional persona of the poem. But it’s not always so clear cut.

This kind of analysis is like training wheels, best discarded when the time is right. :-)

LikeLike

You seriously ROCK! Thank you very much for going to the trouble to help me. This was extremely nice of you. This has been such a help and I’ve learned alot. You’ve helped me look inside the poem and the person. I hope you have a great week! Thank you again.

With big smiles :)

Marina

LikeLike

Me? Rock? Nah… what’s the use of knowing something if we can’t pass it along. :-) Have a great week-end.

LikeLike

Hello again! I was wondering if you had an analysis, that you wouldn’t mind sharing with me, about John Keats and Emily Dickinson and the comparison and contrast of their writing styles of their poetry? I really enjoy how you explain the poem, and the poet, in your commentarys and I know I could learn alot from you and your analysis to assist me in writing this next essay. Anything, you could comment on I know will help me achievie an understanding of these two poets in order to write an outstanding paper. I truly appreciate your insight and knowledge. I look forward to hearing from you. I hope you have a wonderful day! Talk to you soon, Marina (Fort Bragg, California)

LikeLike

P.S.

I’m not trying to be rude. You just seem like the best person to ask. I have been searching the internet and have been so annoyed at the the lack of decent commentarys. You explain things very well and I appreciate that.

Take care :)

LikeLike

I thought you were assisting your son? ;-)

No to worry…. Can’t write your paper for you but I’m glad to point you in the right direction. I haven’t written any analyses comparing Keats to Dickinson, but here are some places to look: What forms did Keats use? What forms did Dickinson use? (I wrote a post on Dickinson and the forms and rhymes she used.) Where did each draw inspiration for the forms they used? What kind of rhymes does Keats use as opposed to Dickinson? What meters did Keats use? Look for his readings of Shakespeare and Milton for example (you can find this information in any good biography on Keats). What meters did Dickinson use? The two of them were influenced by very different traditions. Keats reveled in the literary tradition of England, going all the way back to Chaucer, but wasn’t a “religious” person. DIckinson was classically educated and well-read in the classics, but she took her inspiration from more contemporary experience. She loved music as a child and enjoyed the religious experience. Combine her love of music and song (and the singing of hymns) and you will begin to understand the sources of her inspiration.

LikeLike

I am helping my son. He has an attitude that is making it difficult to complete these assignments, and I want him to get a good grade. He is having a hard time understanding that an education is the basis of life and any doors opening in his future. I just got custody of him recently and am trying to undo alot of damage. I just broke my back and right leg recently and I don’t have all the energy I normally do. So, it makes it difficult to impress upon him how important all this is. I am trying to show him that writing these assignments aren’t all that difficult. That you just need to research abit and talk to people and you will get doors to open and learn so much in return. I guess I’m rambling, didn’t mean too. Just wanted to say thank you once again and to let you know that you really helped us out alot. I wasn’t ready for these assignments, but I got through them. Hooray!

You are very cool and very interesting! Take care

LikeLike

Well we got through the essay! Thank you for pointing us in the right direction. I, not my son, am now a fan of both Emily Dickinson and John Keats. Both are incredibly interesting. Though I must confess I enjoy John Keats much more. My son, no opinion just glad the assisgnment is over. You pointed us in the right direction and it helped. Thank you. I read some of your poetry. Some of it was enchanting.

LikeLike

Hey, “upinvermont,” this is “Suzanne” from Amazon (don’t ask about the name differences unless you want to be bored) following up on our discussion of Keats’ metrics. For anyone interested in following the discussion, I’ll copy/paste our two initial posts to each other and then type out my reply.

Mine:

“I did very much enjoy your commentary and analysis, though I definitely have some quibbles over your scansion (but such is the nature of that most imprecise of poetic arts). I tend to stress in more places than you, especially many of the monosyllabic adjectives. To me, that first line is composed to make a metrical parallel between “Bright star,” “stead-fast,” and “thou art.” None of these are quite spondees or trochees, but that tricky middle ground in between where the second syllable has a slight falling off of accent, but not as much as, eg, conjunctions.

On this: [[[But Keats was writing in a strong metrical tradition. As I’ve said in other posts, if one can read a foot as Iambic, then one probably should.]]]

Keats was writing in a strong metrical tradition, but he was also writing long after the age of “metronome” pentameters. In the wake of Shakespeare and Milton every poet understood the importance of metrical variation and its effects to the extent that iambic pentameter is more like a “ghost meter” (as one critic noted, though I forget who) that underlines but never dictates a poem’s stresses, especially not the extent of any accentual wrenching. Donne is perhaps the most crucial example where stress is always dictated by sense even at the butchering of the iambic pentameter. Keats was more precise, more “Miltonic” in his tendencies towards variations (meaning that most variations dictated a necessary return to the iambic base for re-establishment), but I certainly don’t think we should rule out the possibility that the stress should go on, eg, “would” instead of “I.” There are arguments to be made for both.

BTW, do you know of any books on poetry that attempts to reconcile meter and grammatical syntax? I’ve always been disappointed that most speak of meter as something apart from grammar instead of something quite intricately related to it. EG, it’s always struck me as odd that a meter would dictate we split up a multi-syllabic word when it’s words and syntax that initially dictate how rhythm is formed in our mind when we read. To take the Bright Star poem as an example, it seems to me that that first line is structured around the rhythmic parallelism of “Bright Star,” “sted fast,” and “thou art,” so it would be most logical to take these three as self-contained units. Of course, this makes a “metrical mess” out of the rest of the line (as it leaves “would I were” and “as” oddly alone and amorphous; though one could make a critical insight with that, as if it’s rhythmically separating the speaker from the subject, enacting in rhythm what the line is stating), but I think that’s where that pentameter “ghost” saves it from seeming a mess. But if (a big “if,” maybe) that’s how we read it in our head then I would think that should be the dominant rhythm. I’ve often wondered why I see so few critics and scholars try and map a more polyrhythmic approach to poetry.”

Yours:

“I don’t argue with anyone over scansion. Others have commented or disagreed and I’m fine with that. The best that I can do is to give my reasons for scanning the way I do and let the readers decide whether they agree. The problem, to me, with reading those feet as trochaic is that Keats (elsewhere in his poetry) is a very conservative metrist. A trochaic first foot is nothing, but a trochaic final foot would have risked the criticism that he was incompetent (and Keats was still young & sensitive to that kind of criticism). But he was a genius too. I think he knowingly made use of the meter to create a spondaic foot. An actor could even read the final foot of the first line as an Iamb. But… you should come on over and comment at the blog. Others might be interested in your opinion. There’s an added benefit. I try to be much nicer because I’m the host.

Donne doesn’t butcher meter. A more apt criticism is that he’s willing to take much greater liberty with effects like synaloepha. The problem is that most modern edited texts completely eliminate Donne’s own cues as to how to read his lines. I talked about this very issue in another of my posts.

//Keats was writing in a strong metrical tradition, but he was also writing long after the age of “metronome” pentameters.//

Yes, but for all that, Keats remained very conservative. Off the top of my head, I can’t think of a single trochaic final foot in any of his poems. It’s not a question of ruling readings out. It’s more a matter of seeing what the poet does elsewhere. What are his habits of thought? What can we expect? What can we justifiably assert and conjecture (while, ahem, admitting that we do so).”

My reply:

[[[The problem, to me, with reading those feet as trochaic is that Keats (elsewhere in his poetry) is a very conservative metrist… It’s not a question of ruling readings out. It’s more a matter of seeing what the poet does elsewhere. What are his habits of thought? What can we expect?]]]

This begins another meta-discussion about whether we do and whether we should read poetry as poets intended it or rather how it would be naturally read. I’m of the opinion that the latter is much preferable, but qualified with that we should situate it in its historical context. EG, you mentioned Donne’s synaloepha and such a device was very common in his day, and we should try to “honor it” as they would’ve in his time. However, honoring such things is incredibly tricky because we have limited access to how things were spoken in that time. Even if we did have access it still presents the problem of to what degree poetry would’ve been spoken/read as natural speech would have.

The reason I generally tend towards natural readings rather than metrical readings is because it becomes too easy to wrench syllables to make them fit a meter, and it can very easily cause us to miss metrical effects that were intended. When I first read Milton I found myself doing that, and after reading criticism of Milton’s metrical effects I discovered how many I’d missed by “forcing” lines into iambic pentameter. So that’s why my general rule has become to simply read rhythm in the context of sense rather than the reverse.

So, in that context, I think the question isn’t how conservative a metrist Keats was, or even what meter he “intended” with a line or how he would’ve read the line or would’ve expected others to read it, but rather how it would naturally be read. I’m not saying that “natural reading” presents us with any fewer problems than purely metrical reading (it’s not as if even in daily use our accents are consistent; they vary based on mood and the subtle meanings underlying various statements, questions, etc.), but I do think it, at least, makes “sound (in this case, accents) an echo to the sense” (in Pope’s words) rather than sense being an echo to the sound. The sense has to come first.

[[[Donne doesn’t butcher meter. A more apt criticism is that he’s willing to take much greater liberty with effects like synaloepha. The problem is that most modern edited texts completely eliminate Donne’s own cues as to how to read his lines.]]]

Well, Redpath indicated synaloepha in his edition of the Songs and Sonnets, but I hardly think this eliminates the metrical difficulties in Donne. One thing to keep in mind (that Redpath points out, IIRC) is that Donne did write much of his poetry to be sung and that he kept music’s greater ability to manipulate rhythm in mind when he wrote poetry. So the “inconsistencies” in Donne can be thought of as his thinking more in musical prosody rather than in poetic prosody. And we do have accounts of his contemporaries speaking to his metrical irregularities (Ben Johnson’s famously reported statement that he deserved hanging for not keeping the accent).

It was actually my thinking about Donne’s metrics that convinced me that there needed to be more interrelated study between grammatical syntax and poetic rhythm. Not that we should do away with classic metrics, but merely that these metrics be the “ghost behind the rhythm” to which the sense dictates another rhythm on top of it. This would actually bring poetry closer to music, as this “ghost meter/sense rhythm” relationship would be akin to “time signature/melodic line”.

Although, Donne would still present numerous problems in terms of how he should be read. One consistent problem with him is his clustered groupings of monosyllabic words that would usually be stressed. Because it’s unnatural in English to use consistent stresses for two (or more) straight syllables this presents tremendous problems for where, how, and to what degree accents should fall. A good example of the fits Donne give classic metricists fits is something like the opening quatrain of Twickenham Garden:

BLASTED with sighs, and surrounded with tears,

Hither I come to seek the spring,

And at mine eyes, and at mine ears,

Receive such balms as else cure every thing.

That first line opens with three perfect dactyllic feet* and a curtailed ending. The second foot is a more traditional iambic tetrameter with a trochaic opening (which still maintains something of the “ghost” of the dactyllic first line), the third line is perfect iambic tetrameter (even with the classic medial caesura), while the final line has Donne’s accentual cluster problem. It’s relatively easy to read it as perfect iambic pentameter, but monosyllabic adjectives (like “such”) usually have a light stress, and it’s even more awkward not to stress “cure” and to stress “else”, yet it’s just as awkward to turn “cure ev(ery)” into a spondee.

It’s a place like this where I think the “ghost meter/sense rhythm” thing makes most sense. We can still say that iambic pentameter/tetrameter is the ghost rhythm, but that lines like the first and fourth have a more dominant rhythm over it, and that something like the second finds us in a transition between the dominant first line rhythm and the ghost meter. However you slice it, I still think that last line doesn’t fit in rhythmically with this quatrain. Actually, under my sense rhythm rule the first line makes the most obvious rhythmic indication in the grammatical paralleling of “Blasted with sighs” and “…rounded with tears,” a “choriamb/pyrrhic/choriamb” rhythm.

*It is possible to suggest that the “and” in the first line should be stressed. The argument is that it comes after the caesura and that it would would maintain the pentameter/tetrameter/tetrameter/pentameter pattern of the opening stanzaic quatrains. But it’s a classic example where Donne just doesn’t like to cooperate, because even the second quatrain, while easier to read as iambic pentameter, still maintains a very clear Pyrrhic second foot that keeps a four-accent line. Plus, stressing “and” is usually a no-no, especially immediately following another stressed syllable. It’s usually only done for emphatic effect in the context of a list, and I don’t think this is such a situation.

LikeLike

I don’t know if you will read/get this since the last post was 2 years ago but….. Wow, I have always loved reading poetry even if I don’t understand it. It gives me a sense of release and controll since some poems could have had different meanings. I love how you explain everything and especially how you broke all the meanings. Thanks!

LikeLike

Hi Zaira, I more or less treat every post like it was written five minutes before – going back regularly to add and change. It’s never too late to comment. :-) I’m glad you commented and that you liked the post.

LikeLike

Phenomenal commentary. I fell in love with John Keats’ work after watching Bright Star when it was released and have since been reading the complete poems and letters. Keats is to me symbolises what poetry truly is. I mean the letters to Fanny Brawne alone in the film when she keeps the butterflies in her room were enough to send me in a daze in a mist of an unknown world of poetry. Your commentary is superb and I will be following you from now indeed. Thank you for this by the way. Out of interest, has Keats’ work influenced you as a writer too, in spite of any of the parallels he may have had with earlier writers like Shakespear?

LikeLike

And how.

Mostly, what I took from Keats, by way of appreciation, was his genius with imagery. It’s one of the reasons I have so little patience with modern poetry. Nearly all of it feels written by kindergartners when compared to Keats. To me, poetry lives and dies in its imagery. Whether it’s rhymed, metered or otherwise traditionally written comes second. Truly. But since you ask, here are two poems (for the first time ever) when I was completely enthralled by Keats. (My way of learning poetry has always been to steal from the masters.)

Death I do not fear, though death comes, I know.

That earth shall all this borrowed dust reclaim

And bury me – yes- why dwell in sorrow?

Like to the day I came, I’ll go — the same.

I’ll go; yet, know before this hand’s warm blood

Congeals in chilled veins; before deft years

Rob the pliancy of my limbs and mud

Drains my liquid life and our mournful tears;

Life’s outward expense inward enriches –

An embryo grows, heir to life’s decay

Which, swollen with a lifetime’s wealth, pitches

Into eternity. Like to the day,

That I was born an infant from the womb,

My soul shall be borne, in infant, from the tomb.

Did you see what I stole? :-) Here’s the best of my Keatsian homages:

When frost furls the late-blossomed pageantry

And sends its hurried brilliance swirling

Drowsily to the ground; and gradually,

Fades the days into a pale brown ceasing;

When chill breezes chime the dry, tindered leaves

And twine the trees in dark interlacings;

And clap storm shutters closed beneath the eaves

Guttered thick with the congeal of driftings;

When quick mists coil stealthily in the night

And leave the fields silvered in a brittle glass;

And when in wisps it melts into a flight

Arising with dawn from the glistening grass —

Upon the sweat and strain of wings outspread,

Summer, to warmer southern skies has fled.

So… this is what I was writing when I was just starting out. If I had any sort of artistic ambition at all, I would have burned them a long time ago. ;-)

LikeLike

You CAN definitely see the Keatsian influence in those last two pieces, though I don’t think either deserves burning. They’re very clearly experiments with imagery dominated poetry. All that’s lacking is a rhythmic nuance and control over and exploitation of the sonnet form. Here were two of my pieces influenced by Keats:

“A Day in Life”

The silent rising sun adorns the dew

As eaglets drink the milky mist in nests

Caressed in ease by Mother Nature’s breasts

On mountainous summits meeting days anew.

The noontide touches on the walking shores

And leaves this solid shell for open skies

To win or lose itself in truth and lies

For peaceful life in pregnant inner wars.

My mistress moon communes with sleepy seas

And speaks through mouths of clouds and wordless winds

That creep through minds that never comprehend

Cabals relating through conspiring trees.

For blind and deaf, the old and young, the dumb and wise,

Eternal life and death passes before their eyes.

“Late Summer”

A gold wave washes the southern evening heat;

Cicadas cling to the creviced trees,

Tuning their crying choirs up to C;

As fireflies spark and keep up the beat,

Arthritic rocking chairs creak, the seats

Depressed, slowed down, muted—too old to be

Like the running and the screaming legs as they flee

In the yard and crunch draught-dried leaves under their feet.

Hot dogs crackle on the grill—fragrant meat;

Moms, dads, daughters and sons serve he and she,

The young and old, all together—three

Generations gathering close to eat.

This symphony of summer quiets, decrescends;

Fires fade, darkening gold the crescent sands.

I’m a big fan of imagery myself, but I’ve also come to realize that my favorite usages of imagery are almost always set against a background of non-imagistic poetry. A perfect example is Shakespeare’s Sonnet 29 where the imagery is suppressed for 9 lines, and then the “lark at break of day arising” seems to “break through” the string of abstracts right at the climax/turn of the poem. While I do adore Keats, I sometimes get the feeling that reading him is like gorging one’s self with fudge cake topped with chocolate icing with a side of ice cream. I miss “the salt” that makes such sweetness “pop” like you get a profusion of in Donne and Shakespeare.

LikeLike

…”While I do adore Keats, I sometimes get the feeling that reading him is like gorging one’s self with fudge cake topped with chocolate icing with a side of ice cream. I miss “the salt” that makes such sweetness “pop” like you get a profusion of in Donne and Shakespeare.”…

Oh the chuckles at the fudge cake analogy. A little harsh but your argument is somewhat justified. I truly admire both poems “A Day in Life” and “Late Summer”. The only thing is that while I do admire the content and imagery in them both, and appreciate the rhyme, I warm easily to free-verse as I find it raw and liberating. And raw is great, isn’t it?!

Sometimes I struggle to read rhyme poetry without feeling a sense of it being forced due to the rhyme or it being a result of a never ending edited poem. Free-verse just feels, to me, a result of pure inspiration. (Although it is not the case always). Of course most, if not all, the writing books say one shouldn’t rely upon inspiration striking, but cultivate the ability so that the inspiration is better guided (and has more opportunities to strike)…but still, those flashes are so enjoyable and often do yield the best poetry in my humble opinion. Anyway everyone has their own technique and style. I love Keats’ style maybe due to the fact I resemble his personality in my own writing I suppose. I am still learning and am loving the way I am swooshed and swashed away by all the waves of sensual imagery Keats brings.

Thank you for sharing your two beautiful poems Jonathan.

LikeLike

These sonnets definitely remind me of my own first efforts.

The first sonnet strikes me as being more under the influence of Keats than the second, but there are definitely echoes in the second: “Cicadas cling to the creviced trees”, “draught-dried leaves” “darkeneing gold the crescent sands”.

And you know… both of our efforts are comparable to Keats’s first efforts – just as over the top, mawkish, and sentimental. :-) But, as far as early efforts go, nothing you shouldn’t be proud of. A knack for imagery is all there.

Thanks for posting these! Hopefully, we’ll inspire more readers to post their own effort while writing “under the influence”.

And where is your current poetry? I want to read it.

LikeLike

Bravo..I didn’t actually anticipate the “how?” part but thank you. :-) Yes, I agree (without seeming like a nodding dog) on the imagery Keats would bring and to be honest it is also in the style in which he brought it in. For me with Keats , it is his style and imagery. And to an extent his personality shone through his work and I can relate to it because like Keats, I have been seen as a sensual writer at most. You say “My way of learning poetry has always been to steal from the masters.” But is that not what we all do with any writing? Correct me if I am wrong but aren’t we all, as they say, walking on the shoulders of giants who existed before us?

The first poem is brilliantly written…exquisite although the theme is dreary in a way. This is exactly what Keats was about. Look at Ode to Autumn. It’s ingenious. So in that, I did see what you stole. Although I wouldn’t call it stealing. We all learn from the greats, no denying that. Heck, they don’t even need to be greats and we will still create a synonymous style or ways of writing. Keats’ autumn poems still inspire me as they are insurmountable in meaning and unaffected by time.

The second poem is just AMAZING! Very palpable, poignant, and so like Keats. The imagery, oh my, the imagery, textures and scene are all perfectly laid. “When quick mists coil stealthily in the night//And leave the fields silvered in a brittle glass;”…This is the one of the best Keats-like poem I have read. Amazing!

And NO NO NO…do not burn them EVER. I heard a wise saying once, “when you burn books (writing), you burn people”.

LikeLike

Altair. You embarrass me. But thanks. :-)

With praise like that, I’ll soon be posting poems I wrote when I was six. But as to standing on the shoulders of giants, I agree. I think, sometimes, there’s too much hesitance to take influence from the poets we admire.

LikeLike

RE Altair: [[[I warm easily to free-verse as I find it raw and liberating. And raw is great, isn’t it?! Sometimes I struggle to read rhyme poetry without feeling a sense of it being forced due to the rhyme or it being a result of a never ending edited poem. Free-verse just feels, to me, a result of pure inspiration.]]]

The verse VS free verse debate has largely dominated post-20th century poetry, and there are staunch advocates on both sides of the camp. Our wonderful host, Mr. Upinvermont is heavily on the verse side. Personally, I don’t think it should be an issue. Rhyme, verse, form, etc. are just expressive tools that a poet can use no differently than a filmmaker would use lenses, angles, editing, etc. The modern attack against verse is precisely what you claim, that rhyme and meter “forces” lines into unnatural diction and syntax, that it becomes predictable and fatiguing to the ear, that it’s too “artificial” etc. Personally, I don’t buy any of these arguments because all art is innately “artificial,” and so much of what many find raw, liberating, genuine, etc. is no less artificial and manipulative than anything else.

Free verse, like anything else, is just a matter of what expressive tools are lost and gained. You lose meter and rhyme, you gain the ability to freely break lines and structure stanzas. So the emphasis shifts from the “music” of meter/rhyme to the structural dynamic of line breaks and structure. Things like syntax also takes on an elevated import because of the loss of the musical elements. What gives free verse the “aura” of rawness is because it appears unstructured, chaotic, etc. But if free verse is to make for great poetry then it inevitably highly structured. The great free verse poets–Pound, Eliot, Stevens, Whitman, Williams, et al.–all were very, very conscious about how to structure their works by means other than meter and rhyme. And devices such as anaphora (Whitman) and syntactical repetition (Eliot) became kind of “place holders” for rhyme and meter. Something like The Waste Land, in spite of its apparent chaos, is as minutely planned and sculpted as the most elaborate Shakespeare sonnet.

However much free verse may feel like the result of pure inspiration it never can be and never is, and the best free verse–however much it maintains the “illusion” of pure inspiration–is as highly structured and artificial as anything written by Pope or Keats. Auden said that he considered writing in free verse the hardest thing a poet could do as one had to have an infallible ear as to where to break the lines. This is one thing I tried to stress to upinvermont elsewhere that line breaks in free verse often take on the role of rhyme in verse, and any line break should bring something to the dynamic of the piece.

Lately I’ve been experimenting with ways to bring free verse and verse together, or, at least, to use them contrastingly in the context of the same poem. My efforts haven’t been successful (yet), but I can see some ideas beginning to gel and come together. One thing that’s always occurred to me is the expressive possibilities from moving in and out of verse and free-verse, essentially using the latter to “break down” the former, and using the former to “bring order” to the latter.

LikeLike

//Sometimes I struggle to read rhyme poetry without feeling a sense of it being forced due to the rhyme…//

My first thought is to say that if the rhyme feels forced, then the poet’s probably not doing a good job. Rhyme, if it’s done right, shouldn’t even be noticed. The rhyme should feel like an accident of thought and phrase. The very first time I read Shakespeare’s sonnets (as a child), I didn’t even realize they were rhymed. Frost was very proud of this effect in some of his better known poems.

LikeLike

//Mr. Upinvermont is heavily on the verse side.//

You know, I don’t like to think of myself that way, but if the shoe fits…

I find that modern poets tend to not only not get traditional poetry, but they dismiss it for all the wrong reasons; so I have to dig in my heels and not only defend it but explain and demonstrate what it can do and does differently.

LikeLike

@Upinvermont: [[[And where is your current poetry? I want to read it.]]]

Firstly, thanks for the compliments. Secondly, I haven’t been writing much lately because I’ve been concentrating on reading. What writing I’ve done has mostly been film criticism (I review films for Cinelogue.com). What little poetry I’ve written has mostly just been experimenting and trying stuff out, jotting down lines, ideas, outlines, etc. but little has been completed. The last “major” (in the sense I put significant time/effort into it) effort of mine was four pieces I titled “Quartet for the End of the World,” which is even more histrionic than those sonnets above (which are actually fairly subdued by my standards!). If you want I can post it here, but it’s rather long (~200 lines).

Most of my latest pieces have been experimenting with Cinquains, which are one of the few formal poems I can actually compose in my head from beginning to end (with sonnets I might can manage is an octet before I feel I have to write it down or risk forgetting it). I quite like them, though. They force you to condense a concept down to a few select images, and I’ve really toyed around with mirroring every word/idea in any given piece and figuring out how to manage the progression across the lines. There are a ton of structural possibilities in the form that remind me of the sonnet. Here’s a few of my better (IMO) efforts (titles are also the first lines):

Rowboat

That’s tethered to

Rotting wooden ballasts

On Moonlight Pond, glowing coldly

Tonight

As mists

Paddle mainland towards the pier,

Rocking, wobbling—balanced—

Near gathered storms,

Waits by

——————————-

Snowfall

Enshrouded field

Hushed with lightning whiteness

Dismantled tree—thunder, ravens

Rise slow

——————————–

Sweat drops

Air, thick’ning, Swells

Heat waves~~Gel—Dense Concrete

liquefying into a sea

Then, rain

———————————

Breathing

In tune and time

Fragile carnal statue

A song in stone—broke in moments

By sighs

———————————-

Passing

A cloud above

Lonely floats—becoming

It rains below, cleaves, and sinks to

The Earth

Crawling

From here to there

Slowly moving—learning

Horizons stretch, straighten upward

Erect

Standing

From still to start

Transitory—stasis

To run or fly? Time and being

Are one

Walking

From there to here

Quickly learning—moving

But sleep is still; restful moments

Revive

Pausing

What’s done is done?

Same old state this—being

That time and rest, moments wasting

Too soon

Forward,

Below, and back

Knowing time is—losing

A being, lost… Stretches outward

Away

Passing

From here to there

Transitory—stasis

But sleep is still—moments wasting

Away

—————————————-

Yume

In the distance

I see you in a form

Whispering silence in twilight

Move me

Standing

Still, a silk dress

Cover, transparent pearl

Flowing under the lambent moon

Like milk

Rippling

With a toe’s touch

On ponds of silver glass

Reaching out towards remote shores

Fading

Halo

Luminous glow

Rays caught in a prism

Refracted through your crystal shape

Angel

Vision

Of waving grass

Tickling your tender feet

As you drift just above the Earth

Wonder

Falling

Soft rain and leaves

A paradox in spring

Under a lucid midnight sky

Let fall

Fields of

Honeysuckle

Clover and magnolia

Mix in perfumes that waft across

The scene

I hold

My breath and pause

Knowing that if I breathe

Like a butterfly in my hand

You’ll stir

Yume

Do you know me?

Could I ever touch you?

Hold you close for warmth in winter?

Softly

I fear this is a fragile dream

Soon to fall and fracture

Shatter around…

You, Me

LikeLike

I forgot to mention that the longer pieces were me seeing how the form could work when elongated into something approaching a more typical lyrical/narrative type of poetry, as opposed to just being purely imagistic. Passing is my first/only attempt at a Garland Cinquain, and it made me realize that I haven’t mastered the form even remotely well enough to attempt such longer variations. Yume I like better if only for the images and the play on yume/you me, but as an experiment in form I think it’s a failure. Rowboat, a mirror cinquain, I think worked much better. I think it taught me that any elongated form of the cinquain can’t abandon two elements I think are necessary for the form to work–the first being the “mirroring” aspect, and the second being the careful placement of the kireji, or what’s known as a “cutting word” in Haikus, which I think can only work in English through punctuation. IMO, the choice of what punctuation and its placement are essential for writing a good Cinquain, and I’m still figuring out what effect each can have (mostly it’s just been em dashes, but I think I’m going to have to begin trying others if I want the form to have any diversity. I like the effect of the tilde in Sweat Drops, eg.)

LikeLike

Pingback: Rhythms Of Richard Cureton, Shapes Of Keats « Editions Of You

“I forgot to mention that the longer pieces were me seeing how the form could work when elongated into something approaching a more typical lyrical/narrative type of poetry, as opposed to just being purely imagistic.”

I did feel the ‘natural’ lyrical/narrative style you employed indeed. I think the images are so much more powerful as a result. I know you disagree with my stance on the verse vs free-verse debate but I would like to add that the diction and syntax used in your poetry above, especially Yume, really does compliment the imagery and flow, I feel. “with a toe’s touch//on pond’s silver glass//reaching out towards remote shores…” – and continously too in the poem. That was for imagery. The metrical structure is somewhat similar to small ‘haikus’ of the same string of throughts and feelings brought together in one really good poem. The structure is maintained throughout which makes the composition stand out. In that alone (even though there is no rhyme like ABAB etc) there is an element of craft or artificiality like you said before but technically done so as to get the reader more in the theme, flow and images of the poem, which in my humble opinion was well-done. It sounds natural and I like it. Thank you for sharing these. Apologies for not getting round to reading them at the time of post.

Would you (Upinvermont and Jonathan Henderson and others too please) kindly share your thoughts on the notion that “performance poetry (unlike book poetry, if you like) is not poetry”. Had a discussion, with some peers, which came to a somewhat stalemate. Is it fair to say that it is almost like the verse vs free-verse debate…bound to reach a dead-end? Ian McMillan says “performance poetry is treated like some smelly homeless person who plays the clarinet on the subway.” Will politics in poetry ever end? Isn’t the performance itself ‘the poem’ rather than the words. Who has the right to govern whether performance poetry is poetry anyway? I mean I personally am a ‘book poetry’ lover and writer but still appreciate sound, visual and immediate poetry for various reasons. I would appreciate your thoughts on the matter?

LikeLike

Firstly, thanks for the compliments on my Cinquains. There is definitely a strong structural element to them that is reminiscent both of Haikus and Sonnets. I’ve always felt that Haikus didn’t adapt well to English because English lacks the semantic density of a language like Japanese. The latter allows for a lot to be said/suggested in fewer moras (In Japanese, they measure meter by moras or “sound units” instead of syllables) than can be in English. For me, the Cinquain is a better fit for English because it allows for having, eg, articles and conjunctions if needed while still maintaining plenty of room for the nouns, adjectives, adverbs, and verbs. One key aspect in Cinquains I’ve found is where one places the verb(s). Because Cinquains, like Haikus, are really geared towards imagistic poetry, which is the poetry of nouns and adjectives, the utilization of any “action” word has to make an impact. So, for Rowboat, as an example, I save the verb until the very last line (and even then it’s a “passive” verb). For Yume, most of the verbs are participles. In fact, after “see” in the first stanza, I withhold the next direct verb until the penultimate stanza, the “volta” in that piece.

Anyway, it’s a fascinating form, I think, that I haven’t really seen used and exploited as much as I feel it deserves to be. Most Cinquains I read are just elongated Haikus rather than unique exercises in the Cinquain form.

As for performance poetry, I had a somewhat lengthy discussion with Patrick (upinvermont) on this page regarding the whole “Is X poetry or not?” debate: https://poemshape.wordpress.com/2009/09/15/but-is-it-poetry/

To briefly reiterate the key points of my philosophy, I always think it’s wrong-headed to ask the question “Is A=B?” because almost always when that’s asked what’s happening is that people feel there is both a similarity and difference between their mental associations of A & B. Poetry as a label is a big umbrella that covers so many different discrete elements that it’s impossible to point to any one element and say “this one element makes poetry poetry, and all literary objects must possess that aspect in order to be poetry.” What is really worth asking, though, is what elements performance poetry possesses, and how they’re similar and different to other literary works that we call (not “that are,” but that “that we call”) poetry.

Really, this topic is much larger than the issue of poetry. It really has to do with how people mentally process and think of language. There is a “flaw” of sorts in our cognitive processes that treats language as if meanings are literally in words, instead of meanings merely being associated with words. We run into problems when one word is used to classify multiple aspects of an object. For a complete breakdown on the subject, I’ll give you the link I gave Patrick: http://wiki.lesswrong.com/wiki/A_Human%27s_Guide_to_Words

But, particularly, I want to quote this part that I think sums up the issue as well as possible: “Allow me to paraphrase what [Yudkowsky] said about the debate over Pluto being a planet (in this article: http://lesswrong.com/lw/no/how_an_algorithm_feels_from_inside/): once we’ve determined if a literary work has meter, rhyme, rhetorical patterns, imagery, symbolism, figurative language, wordplay, soundplay, intentional line breaks, etc. then asking whether the work is poetry or prose doesn’t matter; we already know everything there is to know about it. All that anyone is doing after that is arguing how the “center unit ought to be wired up.””

All of these “Is A=B” debates, including “Is free verse/performance poetry really poetry,” is really about how we should “wire up the center unit” in Yudkowsky’s terms. Unfortunately, this creates a very skewered view of how language ought to ideally work.

LikeLike

Just to clarify, the above post is mine. I forgot to log in before I posted it.

LikeLike

“There is definitely a strong structural element to them that is reminiscent both of Haikus and Sonnets. I’ve always felt that Haikus didn’t adapt well to English because English lacks the semantic density of a language like Japanese.”

Yes indeed I too have now learnt the strong structural element (iambic pentameter) in both cinqains and sonnets. I actually never liked the technicalities of sonnets until I got into the habit of writing my own. It is quite liberating when the stresses/feet fit well with exactly what you are trying to craft within the structure. As for cinqains, hats off to you Mr Jonathan Henderson…your “Sweat drops” really is inspiring and I like the ‘Heat waves~~Gel—Dense Concrete

liquefying into a sea’ – effectively palpable, in my view.

I certainly agree that cinquains are not exploited much or rather in my experience, a lot of people will not even prog them with a stick. Reasons why include the syllable restriction. So back again to the “rules” and how some people let that cloud their creative capabilities. I have written cinquains or rather “close-cinquains” if you like, with more than 22 syllables but visually resemble cinquains. With practice and more rule-breaking, the fun that could be yielded in the art of crafting a cinquain can be unmatched. I say so because of the power of verbs and their allusions being more stronger in cinquains, I find, than in other verse. I could be wrong but that’s what I find.

Yes I will read those links you put up now. You are right however about the issue of “X being poetry or not” being more to do with the mentality of people. It always seems to me that people just feel like performance poetry is born of illiterate poets or rather would-be poets. Like it is a lesser art than written/book poetry. I mean if we break down performance poetry itself, using some of the rules used by the “snobbery” that it is not poetry, we will find that no poetry is poetry if read out loud. Because reading out your poetry alone in a workshop, to a friend, spouse or an audience is performance poetry. Even if its written in the most eloquent/elevated style with refined diction and syntax, it will still be “performed”…meaning it is not ‘poetry’ under this view I like to associate with snobbery. I heard a friend of mine say once that “great poets were never made on stage but rather set the stage for what poetry is”…I asked him what then is poetry? Surprisingly he could not pin it down to a single sentence akin to the previous statement he had made. I then concluded and, quote, like Carol Ann Duffy said, “poetry is the music of being human”. Well I didn’t put it so eloquently and concrete like she did but I couldn’t come to one single sentence of what poetry is.

How we define poetry has evolved just like the way poetry itself has over centuries I think. I will read those links you posted Jonathan and respond. Thank you again for your thoughts. Very refreshing.

LikeLike