- October 14 2009 – New Post John Donne: His Sonnet IX • Forgive & Forget

- May 18, 2009 – John Donne & Batter my Heart, His Sonnet

- May 10, 2009 – Bright Star by John Keats, His Sonnet

- April 23 2009: My One Request! I love comments. If you’re a student, just leave a comment with the name of your high school or college. It’s interesting to me to see where readers are coming from and why they are reading these posts. :-)

Donne Wrong

Great Poetry, to me, is like great wine. It takes a lot of wine-tastings to recognize, describe and appreciate great wine. There’s a whole vocabulary and I confess, I don’t know it. I wish I did. So, if someone wants to recommend a good blog or site for the art of wine tasting, let me know. This is my version of the same for poetry.

At the Poetry Foundation I’ve been involved in an interesting discussion on John Donne’s Sonnet: Death be not proud… As part of the discussion I started searching the web to see what others had written. (I especially wanted to find readings and performances.) But, to my astonishment, I saw that everyone was misreading the poem!

At the Poetry Foundation I’ve been involved in an interesting discussion on John Donne’s Sonnet: Death be not proud… As part of the discussion I started searching the web to see what others had written. (I especially wanted to find readings and performances.) But, to my astonishment, I saw that everyone was misreading the poem!

As it turns out, this Sonnet (like Shakespeare’s Sonnet 116) is one of the most misread sonnets in the English Language.

Julian Glover offers a (sort of) period performance in front of a suitably medieval fireplace. Glover was trained with the Royal Shakespeare Co. and, of all actors, should know how to perform Iambic Pentameter. But, astonishingly, Glover misreads it. He’s not alone. I couldn’t find a Youtube performance that reads the Sonnet correctly.

Audio recordings? I checked out the Gutenberg Project and Librivox. They misread it too!

What do they get wrong? Consider the first line:

DEATH be not proud, though some have called thee….

They all pronounce the word called as monosyllabic. It’s not. It’s disyllabic – pronounced callèd.  Here it is, performed correctly in a composition by Benjamin Britten (who music’d all of Donne’s Holy Sonnets). The performance is by Ian Bostridge and clicking on the CD’s image will take you to Amazon:

Here it is, performed correctly in a composition by Benjamin Britten (who music’d all of Donne’s Holy Sonnets). The performance is by Ian Bostridge and clicking on the CD’s image will take you to Amazon:

However, if that’s not evidence enough, here’s something from a composer much closer to Donne’s lifetime – G.F. Handel:

…and His name shall be callèd Wonderful, Counsellor, the Mighty God…

If you listen carefully, you will notice that Handel, and presumably his librettist Charles Jennens, treated callèd as a two syllable word. While the pronunciation of the past tense –èd was rapidly fading from common parlance, it was still alive and well in poetic convention even a hundred years after Donne’s career. In Donne’s own day, when language was much more in flux, this older pronunciation could be found in common parlance too. For this reason, since spelling had not been standardized in Elizabethan times, poets frequently, though not always, used spelling to indicate whether the –ed should be pronounced. In Donne’s case, rather than spelling called as call’d or calld, which was frequently done with other words, he left the e intact.

Here are some other examples from a facsimile addition of Shakespeare’s Sonnets:

Powre instead of Power

flowre instead of flower

alter’d instead of altered

conquerd instead of conquered

purposd instead of purposed

In all these examples, the e has either shifted position or has been removed and in all these examples, the e was not meant to be pronounced. On the other hand, consider the following:

Sonnet 116 ever-fixed mark

Sonnet 92 assured mine

Sonnet 81 entombed in men’s eyes

Sonnet 66 disabled

In all these examples, the e was left intact. Modern day editors, in an effort to make sure the words are pronounced correctly, write them as follows: ever-fixèd mark; assurèd mine; entombèd in men’s eyes; disablèd.

They also modernize the spellings of words like conquerd (since there’s no longer any risk that a reader will mispronounce conquered as conquerèd). The end result is that reader’s aren’t exposed to the kinds of devices Shakespeare and others used to signal pronunciation.

Donne Right

Here is a scansion of Donne’s poem. Purple indicates a spondaic foot. Red indicates a trochaic foot. These colors are my own invention. As far as I know, I’m the only one to use this sort of scheme.

July 27 2009: Me reading the poem

I’ve had some requests to read this poem the way it might have sounded in Donne’s day. So. Mea culpa. I apologize profusely to all actors who can wear an accent as though they were born to it. And I apologize to every reader who speaks the Queen’s English. You must be horrified. I invite any of you to send me a proper MP3, and I will dutifully add it to this post.

I accept all criticism.

Here’s the reason for my effort.What may sound like slant rhymes in our day, eternally and die, were probably much closer, if not identical, in Donne’s day. While nobody can recreate the accents of the Elizabethans, we can make educated guesses based on the kinds of words they rhymed. According to what I’ve read, many scholars think that the London accent of Elizabethan times may have actually sounded just a touch more American than British – think of the classic Pirate’s accent in movies. London was a sea-faring city.

I’m trying out my second recording. I tried too hard with some of the accent. I think I’ll try again, maybe later today.

- For more on Elizabethan pronunciation, here’s an interesting tidbit: The real sound of Shakespeare? (Globe theatre performs Shakespeare’s plays in Shakespeare’s dialect)

The First Line

So, let’s go line by line. The first line, like Shakespeare’s Sonnet 116, seems to give modern readers the most trouble – readers unaccustomed to reading Iambic Pentameter. Here is how many readers read it:

This makes the line Iambic Tetrameter with three variant feet: a headless first foot, an anapestic second foot, and a feminine ending. Historically, Donne would never have written a line like this as part of a sonnet, let alone as the first line. There is no Elizabethan who wrote anything like this in any of their sonnets. Just as in music, there were conventions and rules. Iambic Pentameter was still relatively new and poets wanted to master it, not break it. The reading above, a thoroughly modern reading, would have been scandalous and ridiculed.

Here is another version I have heard among modern readers:

This makes the line Pentameter, but not very Iambic. Every single foot is a variant foot: a headless first foot, trochaic second third and fourth, and a spondaic final foot. Donne would have been ridiculed as incompetent. Some readers, continue the trochaic reading through to the end (making the line Trochaic Pantemeter) :

No Elizabethan poet would have offered up a trochaic final foot – let alone a trochaic line within the span of a Sonnet. The trochaic final foot, with an Iambic Pentameter pattern, didn’t show up regularly until the start of the 20th Century. Between these three scansions there are variations but these examples cover most of them. Some of the misreadings occur because readers simply aren’t used to reading meter, and some because readers, misreading callèd, simply don’t know what to make of the line.

What is worth noticing in all these readings is that DEATH receives the stress. As modern readers, we want to read the sonnet as though Donne were addressing a character on stage. Hey, Death! But that’s not the story meter tells.

As I’ve written elsewhere: A masterfully written metrical poem has two stories to tell – two tales: one in its words; the other in its meter. The meter tells us that the subject of Donne’s sonnet is Death’s Pride. it’s the verb be that receives the iambic stress, not DEATH (though DEATH should still receive more emphasis than otherwise). The reason be receives the stress is because this is a sonnet about DEATH’s disposition, his pride, his state of being.

DEATH be | not proud, | though some | have call|ed thee

Recognizing called as disyllabic allows us to read the line iambically – more easily making sense of the first two feet.

The Second Line

The second line is still problematic for modern readers:

Mighty |and dread|full, for, |thou art | not so,

The stumbling block is usually the fourth and fifth foot, which readers are apt to read as:

Mighty |and dread|full, for,| (thou art |not so),

And this precisely how Glover reads the line. No, no, no,no… One might concede the trochaic fourth foot as a matter of interpretation, but never a trochaic final foot, not in Elizabethan times – not even Milton, in the entirety of Paradise lost, writes a single trochaic final foot (unless we anachronistically pronounce the word).

In poetry of this period, if one can read a foot as Iambic, then one probably should. Even though it’s possible that Donne read the fourth foot as trochaic, all we know for certain is that he was writing Iambic Pentameter and that the verb art is in a (stress) position. Besides stress, Glover’s reading misses Donne’s argument. Placing stress on the verb art echoes the first line’s be. There is a parallelism at work, a kind of Epanalepsis wherein a word or phrase at the start of a sentence is repeated at the end of the same or adjoining sentence:

DEATH | be |not |proud

Thou |art |not |so

In both cases, the verb “to be” receives the emphasis. Donne is addressing Death’s being which, he will argue, is a non-being. The play on the verb “to be” and being may or may not be a part of Donne’s intentions, but the idea is present in the poem and, perhaps, gains some credence by Donne’s stressing of the verb “to be” in both the first and second line – which, besides the meter, is another reason I choose to stress the verb be over the inactive noun DEATH.

The Third Line

This line offers up another curve ball for modern readers. Many will read it as a Tetrameter line (see the Youtube videos):

Green, as with all my scansions, represents an anapestic foot.

So, with many modern readers (including Glover again), we’ve already introduced two tetrameter lines within the first three lines. No metrical pattern is established and Donne’s Sonnet is effectively remade as a rhyming free verse poem.

Again, if you were scanning this poem, warning flags should be flying. No Elizabethan poet, within the confines of Sonnet, ever varied the number of feet from one line to the next. Never.

A masterfully written metrical poem tells us two stories: If we read the third line as Iambic Pentameter, the meter begins to tell us something. This isn’t a sonnet to be recited, meditatively, in front of a fireplace. This is a sonnet, god damn-it, of vehemence – an argument asserted forcefully. The Elizabethans were a fierce and gameful bunch and Donne was famed for his sermons.

For, those | whom thou | thinks’t, thou | dost o | verthrow

There is derision and defiace in those words! This is a sonnet of defiance. Consider the first two lines in light of the what the meter is telling us:

DEATH be |not proud, |though some |have call|ed thee

Mighty and dreadfull, for, |thou art |not so,

For, those, whom thou think’st, thou dost overthrow,

Observe the repeated thou’s. Donne is almost spitting the personal pronoun. You think you’re so great? Is that what you think?

The Fourth Line

This line is perhaps the least problematic of the first quatrain, but the fourth foot is still apt to trip up modern readers. Readers may want to read it as follows:

This line is perhaps the least problematic of the first quatrain, but the fourth foot is still apt to trip up modern readers. Readers may want to read it as follows:

1 2 3 4 5

Die not,| poor death, |nor yet |canst thou |kill me

We know already that the trochaic fifth foot can’t be right. If one reads the fourth foot as trochaic, then the reader is not only subverting the meter of the poem, but the tale the meter is telling us, the vehemence and defiance of them. Yet again, Donne throws defiance in DEATH’s face with another thou.

DEATH be |not proud, |though some |have call|ed thee

Mighty and dreadfull, for, |thou art |not so,

For, those, whom thou think’st, thou dost overthrow,

Die not,| poor death, |nor yet |canst thou |kill me

After the third stressed thou, I find it hard not to read derision in Donne’s verse. This is no fireside chat. This is a sonnet by a man obsessed with death; who, several weeks before his death, posed in his own death shroud for the making of his final monument.

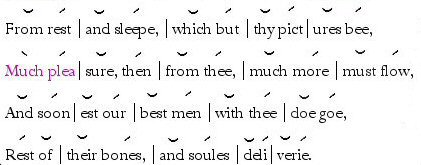

The Second Quatrain

The second quatrain is the least problematic for modern readers. One could read the third foot of the third line as spondaic – both best and men receiving, essentially, the same stress.

And soon|est our |best men |with thee |doe goe,

More to the point is the change in tone from the first quatrain. There is less a feeling of derision and more a tone of confidence and certainty. The meter, accordingly, is smoother and confidently asserts itself. It’s hard to read the four lines as anything but Iambic Pentameter. The first foot in the second line, which I’ve marked as being spondaic, could also be read iambically. There us an almost jubilant certainty in content and meter.

In terms of content. A common conceit was to consider sleep a kind of death. This is what Donne means when he refers to rest and sleep as death’s “pictures”. Sleep and rest are false “pictures” of death, imitations. Sleep and rest were considered healing and restorative. So, says Donne, if sleep and death are but an imitation (a picture) of death, then death itself must be all the more healing and restorative. Much pleasure, he writes in the wise, must flow from death, “much more” than the false pictures of rest and sleep. Brave men must go with death, but it is their soul’s delivery.

The Third Quatrain

The third quatrain illustrates what made Donne’s meter rough and inelegant to his contemporaries. Ben Jonson was quoted as having said: “Donne, for not keeping of accent, deserved hanging.” Even two hundred years later, literary historian Henry Hallam considered Donne the “most inharmonius of our versifiers, if he can be said to have deserved such a name by lines too rugged to seem metre.” Right up to 1899, Francis Thompson was describing Donne’s poetry as “punget, clever, with metre like a rope all hanks and knots.”

Thomas Carew, a contemporary, wrote in his elegy to Donne:

Our stubborne language bends, made only fit

With her tough-thick-rib’d hoopes to gird about

Thy Giant phansie

Carew praised Donne’s meter for it’s “masculine expression”. Dryden, on the other hand, wished that Donne “had taken care of his words, and of his numbers [numbers was a popular term for meter] eschewing in particular his habitual rough cadence. (For most of these quotes, I’m indebted to C.A. Partrides Everyman’s Library introduction to Donne’s complete poems.) It was lines like the following that they were referring to:

Th’art slave to Fate, Chance, kings, and desperate men

The very lines that we, as modern readers, relish and enjoy.

In his own day and for generations afterward, these lines were idiosyncratic departures. I scanned it the way Donne’s contemporaries would have tried to read it – which is possibly the way Donne himself imagined it. I do know that he was working within the confines of an art form that was still fairly new and that too much departure from metrical pattern wasn’t seen is innovative but as incompetent. Anapestic variant feet, within the confines of a sonnet, were rare. To have three anapestic feet within one quatrain would have been extremely unlikely.

The first line is the easiest to read as Iambic:

Th’art slave | to Fate, | Chance, kings, |and des|p’rate men

Since most of us pronounce desperate as disyllabic (desp’rate), reading the last foot as Iambic (rather than anapestic) probably isn’t a stretch.

If the elision of thou art to th’art seems farfetched, here’s some precedent by Donne’s contemporary Shakespeare:

Hamlet V. ii

As th’art a man,

Give me the cup. Let go! By heaven, I’ll ha’t.

Taming of the Shrew I. ii

And yet I’ll promise thee she shall be rich,

And very rich; but th’art too much my friend,

And I’ll not wish thee to her.

Taming of the Shrew IV. iv

Th’art a tall fellow; hold thee that to drink.

Here comes Baptista. Set your countenance, sir.

One might object that Donne hasn’t elided Thou art and therefore means for us to read the first foot as anapestic, but this doesn’t acknowledge poetic practice during his own day. (It’s also possible that he did, but that the printer didn’t correctly reproduce Donne’s text.) In the first line, when Donne didn’t accent callèd, he omitted the accent first, because they didn’t use the grave accent, and secondly, because it was assumed that readers would properly read the word. The Elizabethan audience knew how to read Iambic Pentameter. And since literacy was limited to a fairly limited and educated class, this was a safe assumption. Likewise, and given the strong (and new) expectations surrounding Iambic Pentameter, it was assumed that the reader would elide Thou art to read Th’art. Generally, if a first word ends with a vowel and the second begins with a vowel, and if an Anapest can be reduced to an Iamb by doing so, one probably should. These were the poetic conventions of the day. Poets expected their readers to understand them. Even modern speakers naturally elide such words without a second thought.

And pop|pie’r charmes | can make |us sleepe |as well,

This reading may seem controversial but it’s not so farfetched. Say “poppy or charms” over and over to yourself and you will find that you naturally elide the vowels. It’s simply the way the English langauge is spoken. Donne takes advantage of this to fit extra words into his meter.

I’m not trying to regularize Donne’s meter.

- The point of studying meter, to me, isn’t to fit the poetry to the meter, but to see how understanding meter can teach us something about the poem and how the poet might have exploited it.

Even if we elide all the feet as I have suggested, Donne’s practice still stretches the conventions of his own day. His lines still have an anapestic ring to them. The elision can’t make the extra syllable wholly disappear. He still doesn’t quite keep the accent and still, as Jonson said, deserves hanging. My reason for scanning it this way is to give modern readers an idea of how Donne probably imagined the sonnet.

And better then thy stroake; why swell’st thou then;

Ostensibly, the word swell refers to DEATH’s pride, but Donne also plays on the image of the bloated corpse, a common site in Donne’s plague-ridden day.

The Final Couplet

The final couplet offers a few more opportunities for tripping up. Modern readers are apt to read the lines as follows:

One short sleepe past, wee wake eternally,

And death shall be no more; death, thou shalt die.

This reading, though, misses the emphasis of Donne’s closing and triumphant argument. If read with the meter, watch what happens:

One short sleepe past, wee wake eternally,

And death shall be no more; death, thou shalt die.

Donne’s emphasis is on short. This is not an eternal sleep that awaits us but a short one before we wake eternally. But it’s in the second line that the importance of the meter really makes itself felt. Donne reminds us of the opening lines, of his emphasis on the verb to be:

DEATH | be |not |proud

Thou |art |not |so

And he adds:

DEATH | be |not |proud

Thou |art |not |so

shall | be | no | more

Donne defies Death’s being, making him no more – a no being. It’s not me who will die, says Donne to DEATH, but thou. Thou shalt die!

A Note on the Structure

The structure of the poem is probably most closely related to Sidney’s Sonnets, in terms of Rhyme Scheme, and Shakespeare’s Sonnets (or the English Sonnet) in that 3 quatrains lead to a final, epigrammatic couplet. With typical Elizabethan rigorousness, Donne hammers out his argument. The effect is a little different though. Each of the quatrians encloses its own couplet (see the brackets). The effect subliminally dilutes the power of the final couplet while strengthening (to me) the unity of the sonnet. The rhyme scheme, which limits itself to only 4 distinct rhymes, as opposed to Shakespeare’s 7, also lends to the poem a feeling of organic wholeness and clarity. One can only speculate why Donne chose this rhyme scheme, unique among all the other sonnets being written during his day. For a look at the other sonnets being written in his day, see my post on Shakespeare, Spenserian and Petrarchan Sonnets.

If you enjoyed this post, found it helpful, or have a question, please comment!

Patrick, it’s great to see such a thorough scansion of the poem. Thanks for letting me know about this post.

Annie

LikeLike

Wow! I am an English major at UC Berkeley (a junior now) and I have to say that no professor here has made me appreciation meter in poetry as much as this single post has done. I originally found your blog because of something you had written about Frost and “Birches” (I was writing an essay on that same poem at the time). Spring break just having arrived, I wanted to check the site again to see what else I could find.

I am very happy that I did.

The blog that my name links to is used for some poems and other creative things, but it is all really childish stuff…. I definitely have a lot to learn!

LikeLike

Agh! How did I do that??? I meant to say: “has made me appreciate meter in poetry”….

LikeLike

Thank you so much for the encouragement. If I weren’t sitting in my car, outside a library. I would write more! Hopefully I’ll get a replacement DSL modem today.

LikeLike

Hi, I’m an Italian teacher of English who’s just come across your blog while surfing around to find the correct pronunciation of supposedly rhymed lines 6-8, and 22-24 in Donne’s “A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning”:

(…)

No tear-floods, nor sigh-tempests move

(…)

To tell the laity our love

(…)

Though I must go, endure not yet

(…)

Like gold to airy thinness beat

I’ve heard Burton’s recitation of this poem but he pronounces those endings using modern English phonetics, and therefore they do not rhyme. But shouldn’t they?

Thanks for your help

P.S. Excellent analyses and nice pseudo-Donne puns: “Donne wrong” “Donne right”

LikeLike

Hi Maurizio,

The short answer is that no one knows exactly how the Elizabethans pronounced English. That accent or pronuncation, like Latin, is gone forever.

The long answer is that we can make educated guesses. Some have made the argument, based on rhymes, puns and wordplay, that certain aspects of their pronunciation may have actually had more in common with some pockets of American English.

If you go to the University of California website, you can hear a pronunciation of reason – which was closer to raisin. Since spelling wasn’t normalized during the Elizabethan period, many words were spelled the way they sounded. You will notice that beat uses the same vowel combination as reason. Odds are, yet and beat were both pronounced with something like a “long a” – something like yate/bate.

Love was probably pronounced with something like a Beatle’s Liverpool accent, so that it sounded more like the double “o” sound in the verb look. I have searched for an actual reading but couldn’t find one. If you specifically ask me to, I would be willing to try a reading of it? – just to give you an idea.

At the Renaissance Faire, you might find more guidance.

Nowadays we tend the call these eye-rhymes.

Anyway, as I say, if you want me to give this poem a try (to read it) let me know.

LikeLike

I would love it so much, and since you volunteer please give it a try (a reading). Thanks a lot

LikeLike

Your posts really do interest me, and though you and I know that I do not write poetry by the book, or shall we say, how other people think I should write poetry, this does not mean that I dont enjoying reading posts/poetry like yours or alike.

I have a new post up – my style ;)

LikeLike

Thank your for your rigorous analysis of the meter in Donne’s “Holy Sonnet X”. These formal aspects are too often overlooked. Thanks for making the effort. Very stimulating. Bravo!

-Vincent. (In answer to your one request: I study philosophy (maj), French lit (maj) and English lit (min) at Uni of Lausanne, Switzerland.

LikeLike

Wow! Thanks so much.

My mother just visited us. She lives in Zurich, Switzerland.

LikeLike

Goode evening,

Hope that you are having a good weekend.

I wanted to thank you also for including my poem.

Take care

Stacey :D

P.S…. I love the little green character, it’s so me ;D

LikeLike

wow, thank you so much! this was so useful for my poem presentation!

LikeLike

You’re very welcome!

LikeLike

peace be upon you. I’m a studant in English Literature Department in K.S.A thank you very much for this explaination i’ve just read part of it and I’m raelly enjoyed it and i hope that i have planty of time to raed it all but i have an exam tomorrow and i should prepare well to make up the mid term exam. these information help me a lot. MAY GOD BLESS YOU

LikeLike

No one has ever said that to me. : ) I’m honored. And peace be upon you.

LikeLike

Peace be upon you sir. thank you very much for this analysis. when I read it I realize how ignorant in poetry I am as we say in Arabic “More I learn, more I am an ignorant” I don’t know if i translate this line of verse properly but the meaning is we should not stop to learn. For this I would like to ask you a favor; first can I find an analysis for “Ballad Of Birmingham” and “God’s Will for You and Me” in this website. And the second can you tell me about any sources which help me to learn the basic principles of English poetry . I’m looking for your help with all my thanks. by the way excuse me if I made any mistake either grammatically or in spelling I’m just a learner

LikeLike

Hello Marvareid, I’m equally ignorant of Arabic poetry. If you ever want to translate and analyze your favorite Arabic poem, for inclusion on this website, let me know. I’d be glad to proof your English.

I haven’t analyzed “Ballad Of Birmingham”, but would be willing to do so. “God’s Will for You and Me”, if it’s the poem by anonymous, is straightforward. The meaning of the poem and its subject matter are one and the same. As I say, very straightforward:

The form is rhyming couplets (though these are not heroic couplets because they aren’t Iambic Pentameter) and the meter is accentual, as opposed to accentual syllabic. What this means is that the syllable count varies from line to line. (There is no regular syllabic count.) Some lines have eight syllables, some have ten. In accentual verse what matters is not how many syllables there are per line, but how many stresses or accents. In each line of the poem, there are four accented syllables. That means that four syllables receive a strong stress while the rest receive a weak stress. Most nursery rhymes, in English, are accentual. Most Rap (listen to Arabic rap) is accentual.

If you have more questions, let me know. : )

By the way, as to the basic principles of English Poetry, that’s an extremely broad question. You will have to be more specific. After all, the basic principles of English Poetry are probably universal – meaning that they are the same in Arabic as in English as in Chinese.

LikeLike

Peace be upon you. thank you very much for this help I’m really appreciate your kindness and glad to find someone who can help me to learn more and more. About the translation of the Arabic poetry I think it’s something difficult for a beginner for it might spoil the meaning of the poem I need to be skilled in English language first and than to master poetry as Ben Jonson says and I hope to be able to do so in the future. I considered myself your student and it will be my pleasure if you accept me to be so. MAY GOD BLESS YOU

LikeLike

Pingback: Death be not proud « bonæ litteræ: occasional writing from David Rundle, Renaissance scholar

Pingback: Ryme & Meter Written and Online • September 13 2009 « PoemShape

What an excellent help this was for me as I worked on this poem for a class. Thank you.

LikeLike

Oh, and Im from Hamline University in Saint Paul, MN…

LikeLike

Cool. I’ve only driven through MN while on the way to Washington, State.

Does this look familiar? It was about the only image I could find of the campus.

Thanks for the comment. I wish more readers would say Hello. It’s a little like getting to travel.

LikeLike

Actually, no I dont recognize that. It must be coming from an angle I never come from. Here’s a link to google images that has a bunch of pics:

http://images.google.com/images?hl=en&rlz=1B3GGGL_enUS240US241&um=1&q=hamline+university&sa=N&start=0&ndsp=21

Hamline is a pretty small, private school that I could never have afforded if it wasnt for scholarships. Nice place though, and they have a great English program.

Thanks again, I have found myself coming back to this page again and again for help.

LikeLike

I am a Chinese, thank you for everything you have done

LikeLike

Hello, Patrick,

Very interesting and informative. Until you explained how it was to be heard, I hadn’t appreciated Donne’s spitting derision of death and consequently hadn’t appreciated the sonnet. You should be teaching. Sadly, a Ph.D. is required, while breadth of knowledge, love of subject matter and teaching ability are nice but not necessary.

A typo you may want to fix, that proves you write by ear and not by eye (of course, you’re a poet): “I do know that he was working within the confines of an art form that was still fairly knew ….” And by you fairly known. Donne, well done, indeed!

LikeLike

Thanks, Chaim. Writing the post was an education for me too. I’ll jump on that typo write now. I mean… right now.

LikeLike

Great blog! I’m a high school lit. teacher in CA. I was searching for a place where I could check my Donne scansion in prep for my advanced group. If I didn’t have a worldwide web, I’d want to hang him too. No, I like his work. I really enjoyed your comments, but I loved your oral reading of the poem! I think my students will too.

LikeLike

I think you’re the first to comment on my reading. Thanks!

I always wonder if folks just roll their eyes when they listen to it. Maybe I’ll try Donne’s other sonnet? I’m going to be in San Diego this spring, anywhere near there?

LikeLike

Keep ’em coming.

I’m in the LA area.

LikeLike

Hello! I’m an undergrad English student from Oslo, Norway. I keep coming back to this website as it has the most comprehensive treatment of (selected items of) English poetry I have found anywhere online. I too wrote a paper on Frost’s “Birches” and found your scansion invaluable! Thank you so much for the insights and amazingly clear presentation. I’m now writing a paper on sonnets and yet again find myself gravitating back to your site. I really enjoyed your scansion of the “Death”-poem by Donne – it all makes sense to me now. ;-) Thank you so much!!! I really love this site. I had a very limited appreciation of poetry before I discovered your site, but this has changed now! :-D

LikeLike

Hi Leselykke! Glad you wrote. Comments like yours keep me motivated. I have one more book review to write, then I’ll return to Frost, some Shakespeare, maybe an unknown woman poet from the 19th Century, and so on. I can only ever hope to scratch the surface. And thanks for commenting on my reading! You’re the first.

LikeLike

I would love it if you’d do some Wordsworth. We have “The world is too much with us” on our assignment and I absolutely cannot get my head around the meter in that one; especially the first quatrain. And appearantly he’ve written hundreds of sonnets so there should be some to choose from. ;-) In your own time. I’ll keep coming back anyhow. :-)

LikeLike

I’ve got a book review to finish today, then I’ll write up the sonnet. I was wondering what poem to write about next. What’s your deadline?

LikeLike

Wow, that was quick! Uhm, my first draft is due on monday. A final version in some more weeks. Never mind that, you should not be doing my work for me. I’d love to see what you get out of the sonnet any time it suits YOU. :-) I will focus more on content than form in my essay, so a perfect scansion will hopefully not be required.

LikeLike

I can give you a helping hand with the meter, since I won’t be able to write anything up by Monday. I copied the poem off the internet, so I’m not sure all the punctuation is in place:

The world | is too | much with | us; late |and soon,

Getting |and spen|ding, we |lay waste |our powers;

The word powers can be pronounced disyllabically or as a monosyllable. The first foot of the second line is Trochaic.

Little |we see |in Na|ture that |is ours;

We have given |our hearts |away, |a sor|did boon!

The fourth line is tricky, it could be read as follows:

We have |given |our hearts |away, |a sor|did boon!

But that would make it an alexandrine and probably not a variant line Wordsworth would have been willing to write in the space of an Iambic Pentameter Sonnet.

Here is what he probably had in mind (and what is confusing you):

We’ve giv’n |our hearts |away, |a sor|did boon!

Such elision was a commonplace in metrical poetry (or call it a trick). But this is what Wordsworth probably had in mind. This form of elision is called synaloepha, despite the aspirated ‘h’, in the first instance (We’ve), and syncope (giv’n) in the second instance. Both techniques go back to the Elizabethans and, while some purists may have frowned on them, were recognized ways to fit extra-syllabic words into an Iambic Pentameter line.

This Sea |that bares| her bo|som to |the moon,

The winds |that will|be how|ling at |all hours,

And are |up-ga|thered now |like slee|ping flowers,

For this, |for e|verything,| we are out |of tune;

Speakers naturally elide every to read ev’ry – another example of syncope. The third foot |we are strong| could be considered either an anapestic foot (probably less likely), or an Iambic foot if the reader uses synaloepha to read we are as we’re.

It moves |us not.|–Great God!| I’d ra|ther be

A Pa|gan suc|kled in| a creed |outworn;

So might |I, stan|ding on |this plea|sant lea,

Have glimp|ses that |would make |me less |forlorn;

Have sight |of Pro|teus ri|sing from |the sea;

Or hear |old Tri|ton blow |his wrea|thed horn.

The wreathed should be pronounced as a disyllabic word: wreath-ed.

The form is Patrarchan.

I’ll give it a proper write up sometime this week. :-)

LikeLike

Oh, and I forgot to mention, I listened to your reading today and I enjoyed it! No need for excessive selfconsciousness! :-)

LikeLike

Thank you so much!! :-D Almost speechless – I feel very priviliged for this personal favor. (Add “We’re not worthy”-pose from Wayne’s World movie here.) I will still be looking forward to you’re full treatment of it in a later post.

I will have to read this through some more times. Questions: Should “rising” in line 13 not have the stress on the first syllable as well? “Flowers” in line 7, monosyllabic?

Is there anywhere on your site where you explain the synaloepha v. elision-thing? I’ve never come across the distinction anywhere else. (Not that I’m a very experienced poetry student, but everybody has to start somewhere, right?) :-)

Thanks again, this was lovely! <3

LikeLike

I feel privileged to have readers.

Yes. I just changed it. When I write these notes in the comment field, all I see is HTML (which makes it hard to catch mistakes like that).

Yes, I would lean toward monosyllabic. Anyway, that’s the way just about all English speakers pronounce the word. I suppose there might be some overly fastidious linquists who insist on two syllables.

synaloepha – [the contraction into one syllable of two adjacent vowels, usually by elision (Ex.: th’ eagle for the eagle)]

syncope – [the dropping of sounds or letters from the middle of a word, as in (gläsʹtər) for Gloucester]

:-)

LikeLike

Why did my last comment end up at that place in the “tree”?

LikeLike

No idea. WordPress does weird things with comments. The software is a little buggy, methinks.

LikeLike

My name is Rania and I go to William Paterson University

LikeLike

Thanks Rania! I think I’ve heard of this University, but I’m going to look it up to remind myself. :-)

LikeLike

Good and well-written. I will come back to your site. Regards!

LikeLike

Pingback: “Just a Comma” « Not Quite Lit Theory

I just stumbled across this website when trying to research a school assignment. This is awesome! I was having so much difficulty with Donne’s meter and this has helped greatly. Now I just have to learn to recite it with the perfect meter… Haha thankyou again!

LikeLike

Thanks for the comment, Aura. :-) You’re not the only one who has trouble with Donne’s meter. There are experienced poets and college level instructors who don’t understand meter – almost a lost art.

LikeLike

Patrick, Thank you for this in depth post…

I hav efound it rewarding, and inspiring.

I have been very busy… I hope all is well.

Happy New Year…

Also, I have a gift for you… All the best…

John E. WordSlinger…

http://johnewordslinger.wordpress.com/2012/01/08/kreativ-blogger-award/

LikeLike

Thanks John, I’m flattered & Happy New Year!

I don’t do chain letters any more (stopped a few years ago), but I accept your gesture with all the good will with which it was intended. :-) We should all do what we can to support each other.

LikeLike

Thank you for an analysis that thoroughly covers much needed perspective while remaining accessible to those not as comfortable with poetic scansion. Your discussion increased the enjoyment of the poem and gave me something new to think about. I will be back to check out your other perspectives and observations.

LikeLike

Hey Windo, thanks for your comment. The accessibility of my posts is something that matters to me. Some analyses get so academic that they’re tougher to decipher than the poems.

LikeLike

Guildford High School, Surrey, United Kingdom

LikeLike

I went to Cranleigh School for a year, in Surrey, and know Guildford well. :-)

LikeLike

Hey Patrick, just want to say an enormous thank you for this assessment of Donne’s meter, as a first year uni student writing a critical essay on “Death be not Proud” I have found your writing an invaluable resource. I’m currently attending the University of New South Wales and I stumbled across this page by chance, but I am immensely glad that I did!!

LikeLike

Thanks Ellie, that’s very appreciated; and I’ll be writing more with encouragement like yours. :-)

LikeLike

Thank you for your painstaking analysis. I thought it was very instructive. I have two questions: First, in the fourth line of the third quatrain, shouldn’t the word “then” be “than”? Second, does a manuscript of this sonnet survive? If so, is there a facsimile of it posted online somewhere?

Many thanks,

Derrick Robinson

LikeLike

I am referring to the first appearance of the word “then” in the fourth line of the third quatrain. Thanks again.

LikeLike

Hi Derrick, I’m tempted to agree with you, However, both the Oxford edition and Everyman’s Library Edition, edited by C.A. Patrides, print the sonnet with “then”. This doubtlessly reflects the earliest printing since Oxford’s Edition is based on that. In a footnote to the Sonnet, Patrides also suggests “than”, rather than “then”, so I think it’s safe to read it as “than”. Patrides, in the footnotes, offers alternative versions of the sonnet based on “MSS” (his word), so at least *some* manuscripts must survive but they don’t seem to be available online. I’ll look again. If you find something, let me know and I will link to it.

LikeLike

Hello. I am a French student studying Philosophy, History, Literature, Ancient Greek, German and English. I have an oral examination next week, on this poem, which I must read and comment within the time limit of 30 minutes. I should never have checked the meter scheme online, really, because when I read it out loud myself, I just read it the modern way and it would have been much easier…

So just to be sure, did I get this correctly?

– no one knows how this is supposed to be read and there are many discussions about it

– this is both regular and irregular, because it respects the meter scheme of regular iambic pentameters but it has an “anapestic ring” to it?! (then how are we supposed to read it to render both aspects?)

– no one knows how the two endings of the couplet are to be pronounce, whether they rhyme, or don’t. Perhaps they rhymed at the time, but we cannot be sure. So should I just read “eternallie” like “die” even though it sounds strange nowadays, and not comment at all on the rupture in the rhyme scheme at the end, because there isn’t one?

– the “then” in line 13 doesn’t make much sense to usually we understand it as “than”, but it seems Donne wrote “then”, since even the Oxford edition based on the earliest printing kept it that way. Did Elizabethans spell then and than indifferently? Or are we supposed to try and understand the sentence with “then” and not “than”?

I must say I am overly confused, and even if your post is great, it has wreaked havoc in my mind rather than made things limpid… I have no idea how I should read this poem, and so it is nearly impossible to use the meter scheme in my interpretation – which is absurd, because how can one comment a Sonnet without commenting its form, rhyme and meter schemes? But this poem is shrouded in such uncertainty I truly am at a loss as to what to do.

LikeLike

//- no one knows how this is supposed to be read and there are many discussions about it//

There are two ways to answer this question. If you’re asking: Do we know how Donne read this poem? Then, no, we don’t know how, exactly, Donne pronounced certain words anymore than you would know how Francois Villon pronounced Medieval French. If, by “supposed”, you’re asking: Do we know how Donne intended this poem to be read? Then, yes, we know. In that sense, your assertion is incorrect. It’s not true to say “no on knows how this is supposed to be read”. In fact, we do know how this is supposed to be read because Iambic Pentameter was a firmly established meter by Donne’s time, and with known conventions. You can see those conventions reflected in the way he apostrophized words and the way contemporaries reacted to his poems.

//- this is both regular and irregular, because it respects the meter scheme of regular iambic pentameters but it has an “anapestic ring” to it?! (then how are we supposed to read it to render both aspects?)//

You shouldn’t really be concerned about rendering “both aspects”. That will take care of itself if you respect the meter. If the meter forces you to accent certain words (you might not have otherwise) then you should pay attention to that and try reading it that way. Concerning poems from this time period: If you can read a given metrical foot as an Iamb, then you probably should. As I’m sure you’re aware, English is an accentual language in a way that French isn’t. A little change in emphasis from one word to another can completely change the tone and meaning of a line. The problem is that the vast majority of modern English readers and poets have forgotten how to read Iambic Pentameter, and so utterly misread poems from this time period.

//no one knows how the two endings of the couplet are to be pronounced,//

True.

//whether they rhyme, or don’t.//

No, they rhymed. The only question is a matter of degree, not whether.

//Perhaps they rhymed at the time, but we cannot be sure.//

No, we can be sure that they rhymed. Again, at most, it was a matter of degree. Pronunciation changes over time and in given regions. To my knowledge, Donne (in his own day) was never accused of being a poor rhymer, only of writing difficult meter.

//So should I just read “eternallie” like “die” even though it sounds strange nowadays, and not comment at all on the rupture in the rhyme scheme at the end, because there isn’t one?//

I think that if you interpretively comment on the rhyme scheme as being “ruptured”, your conclusions will be misleadingly anachronistic.

//the “then” in line 13 doesn’t make much sense to usually we understand it as “than”, but it seems Donne wrote “then”, since even the Oxford edition based on the earliest printing kept it that way. Did Elizabethans spell then and than indifferently? Or are we supposed to try and understand the sentence with “then” and not “than”?//

Spelling had not been normalized during the Elizabethan era. All of their spellings, interestingly, reflect their own regional pronunciation. In other words, it’s not that Elizabethans were indifferent, it’s that they spelled words the way they heard and pronounced them. So… I think it’s safe to read “then” as “than”, while assuming that Donne himself probably pronounced our modern “than” more like “then”.

Let me know if this helps. If not, keep asking questions.

LikeLike

Check out the Broadway play turned HBO movie entitled “Wit” by Margaret Edson. Brilliant piece of literature. What do you think of the analyses presented there?

LikeLike

I haven’t seen or read the play. However, I was exchanging E-Mail with someone who told me that the main character, evidently an expert on Donne, wasn’t enough of an expert to get the meter right. (!) The Donne “Professor” apparently gets the meter all wrong by reading “called” monosyllabicly. Oh well… it’s just a play, right? =)

LikeLike

Hello :)

I’m a second year student at University of British Columbia.

I came across your post while doing research for my final paper and I can see that you have put in a lot of effort! I also must admit your pun was quite a rib-tickler.

I really appreciate this post; it helped a lot! Thanks! :)

LikeLike

And thank for your comment. I’m always happy to learn that my posts have been helpful.

LikeLike

This post would be much better if the recording of your proper reading of the poem was still accessible. Currently it is not. Beyond that, I found this to be the most useful post on the Internet on this subject. Thank you for your work.

LikeLike

Good Morning William & Merry Christmas. I have had problems with recordings on WordPress. They get silly finicky about whether HTML is capitalized, but I just checked it and it works. I suspect you may be script-blocking in one way or another? Check script-block, ghost script and adblock extensions (if you use them). Otherwise, I’m glad you enjoyed the post. :-) P.S. I got a click-jacking warning on Firefox [rolls eyes] when I tried the audio-link. I suspect your browser is blocking it for one reason or another.

LikeLike

Thank you for your analysis. It was helpful for composition based on this text for two choirs, two soloists and two percussionists. It will be performed by the MDR Choir on April 29, 2013 in Leipzig. I also adopted the spelling which you used on the website. Could you please tell me the sourse of this version? I might have missed it somewhere on the site.

Many Thanks

Laurence Traiger, Composer

Munich, Germany

LikeLike

Hi Laurence, congratulations. I’ve been to Leipzig. That was shortly before the wall fell. The musical scene was very different then (back when I was still composing). Do me a favor, put a rose on Bach for me. They had roped it off, but that didn’t stop me.

Anyway, I used the Oxford edition, Donne’s Poetical Works, edited by H.J.C. Grierson. However, I don’t recommend you reference Grierson’s spelling. Since then, I’ve gotten a hold of John T. Shawcross’s edition, and it’s better than Grierson’s. He retains some punctuation that Grierson, oddly, doesn’t. Here is Shawcross’s reprinting (I’ve highlighted the important differences in red):

Death be not proud, though some have called thee

Mighty and dreadfull, for, thou art not soe,

For, those, whom thou think’st, thou dost overthrow,

Die not, poore death, nor yet canst thou kill mee;

From rest and sleepe, which but they pictures bee,

Much pleasure, then from thee, much more must flow,

And soonest our best men with thee doe goe,

Rest of their bones, and soules deliverie.

Thou’art slave to Fate, chance, kings, and desperate men,

And dost with poyson, warre, and sicknesse dwell,

And poppie,’or charmes can make us sleepe as well,

And better then thy stroake’ why swell’st thou then?

One short sleepe past, wee wake eternally,

And death shall be no more, Death thou shalt die.

This is from page 342. Double check me. The book is: The Complete Poetry of John Donne: Edited with an Introduction, Notes, and variants by John T. Shawcross. The Anchor Seventeenth-Century Series.

LikeLike

Thank you very much for that detailed reply! When I have a recording of the piece I would gladly share it with you. Interesting, that you also composed! Did you set the poetry of Donne to music? I will gladly pass the the rose to J.S.B for you.

LikeLike

I would love to hear a recording of the piece. If you liked it, I’d be happy to share it on my blog as well.

I never put any of Donne’s poems to music. I did try putting some of Frost’s poems to music and very nearly ruined them for myself. I eventually decided I was much better at listening to music than composing. The one facet of composition that I was good at, was counterpoint. I taught myself how to write fugues and that’s what got me into a conservatory, but that small bit of musical talent only got me so far.

If you would pass that rose to J.S.B., even if it’s in your thoughts only, that would greatly please me. I shed a tear for him while I was there. I’ve always had a very strong connection with Bach’s music and life, starting when I was hardly a year old.

LikeLike

Hello,

An Enormous Gratitude Of My Part For The Analysis of John Downe’s Sonnet, For This Must Truely Be The Work Of An Extraordinary Genius,

I Am Still In High School, But I Do Indeed Look Forward To Better Understanding The Meter,

*Thank You And GOD BLESS,

LikeLike

Nice to hear from you Gloribelle. :-) I’ve written more than a few posts on meter. You’re always welcome to read and ask questions.

P.S. I assume you’re referring to my analysis as a work of extraordinary genius. ;-)

LikeLike

Ohh! Uhm, I Am From California, And I Go To South El Monte High,

*Thanks Again

xx

LikeLike

Tonight my choral setting of “Death be not proud” will be broadcast live from Leipzig at 22:00 central European time. That is 4pm Eastern Standard Time. You can steam it live from the Website of the MDR Figaro.

My piece is second on the program.

http://www.mdr.de/mediathek/livestreams/radio/livestreams

LikeLike

Tonight my choral setting of “Death be not proud” will be broadcast live from Leipzig at 22:00 central European time. That is 4pm Eastern Standard Time. You can steam it live from the Website of the MDR Figaro.

My piece is second on the program.

http://www.mdr.de/mediathek/livestreams

LikeLike

This is the correct address for the broadcast of the concert

http://www.mdr.de/mediathek/livestreams/radio/livestreams102_zc-f4d3cfa5_zs-d1ce8330.html

LikeLike

Thanks Laurence! Got it. I don’t use Windows or OSX. I use Ubuntu. If the Live Stream video insists on Windows Media Player, I may not be able watch. I should have no problem with the MP3 online-radio broadcast.

LikeLike

Leipzig was great and the concert went very well! I did as you said and placed a white rose on Bach’s (presumed) grave. Here are some pictures:

https://plus.google.com/photos/107030103449484883968/albums/5873088916773041665?authkey=CO2orNat466jcQ

When I get a recording I will try to get it to you.

LikeLike

Thank you so much! :-) I can see, just from the photos you sent, that Leipzig has changed very much. It was a gray and bleak place when I was there (still East Germany). I look forward to anything you forward my way. If you send me an MP3, I can include it in my post (all else being equal in terms of permissions).

You are right that this is Bach’s presumed grave. When his original burial plot was exhumed, however, forensic facial reconstruction provided fairly solid evidence that the bones are JS Bach’s. DNA would probably make the evidence iron clad.

LikeLike

My name is Samantha. I attend UTEP (University of Texas at El Paso). I’m a sophomore & English Major and I was supposed to write a written response for some of Donne’s Holy Sonnets. Including how rhythm and meter play into the poem and its meaning for one of them from my textbook. I only just learned meter this past week (they didn’t teach it to me in high school like I believe they should’ve) and Donne isn’t the easiest 17th century poet to scan for beginners. Thank you so much! This helped me a lot =)

LikeLike

Hi Samantha, glad the post helped you. I agree that meter is scanted by nearly all teachers and modern poets, and I think it’s largely because they don’t understand meter, how it’s used, and its importance (to the poets at the time). I guess that’s the niche this blog is trying to fill. :-)

LikeLike

I’m a chaplain at the University of Toronto (Canada) and came across your site when I was preparing for a viewing and discussion, with a group of graduate students, of HBO / Emma Thompson’s film version of Edson’s “Wit,” cited in an earlier comment. The play, incidentally, won a Pulitzer Prize and if you haven’t watched the film yet I would recommend that you do. While you will certainly disagree with some of the interpretation and oral rendering of the poem (I know I do, now that I’ve read your post!), I think you might appreciate the professor’s emphatic insistence that getting the punctuation (and one might infer meter) correct is fundamental to a proper understanding of the poet’s meaning. This point (or rather, comma, as it happens) becomes the vehicle for conveying the elder scholar’s main message about the poem, which in turn provides the central thread of the whole play/film. It was, in fact, exactly that focus on punctuation that sent me on the internet search that turned up your website, and I have now recommended this article to the students who will be watching the film, should they be inspired to explore the poem more deeply. I may even attempt a reading before we watch the film.

It’s been a long time – at least since my undergrad days studying English Lit – since I’ve delved so deeply into a piece of poetry and I thoroughly enjoyed your analysis. Though we certainly looked at meter, and especially Iambic pentameter, in Shakespeare, Chaucer, etc., I don’t recall ever giving it the kind of significance you rightly do here. I’m also curious, now, to go back and read the essay I wrote on Donne’s sermons, having been not nearly brave enough to tackle his poems. Neither your article nor, indeed, the internet existed at the time, but had they, I might have been inspired to press on more boldly. Now I find myself wondering how I might contrive to spend some more time with the Holy Sonnets.

Your reading did remind me, fondly, of a rare but memorable rendition of the first few stanzas of Chaucer’s Prologue to the Canterbury Tales that my elderly Scottish professor gave us one day, lending the accent of his (once suppressed) mother tongue to an interpretation of how the Middle English might have sounded. I can still recite it to this day. That was his area of scholarly expertise, and I’ve always wished that he had read to us more. I would love to know what he would have done with Donne.

Thanks again for your article. I thoroughly enjoyed it.

LikeLike

Chaplain at University of Toronto, eh? When living in Olympia, Washington, I struck up a friendship with a/the(?) Chaplain of the Royal Canadian Navy (whose ship was briefly moored in Olympia). He might have told me he was the presiding Chaplain, but I can’t swear to it. (I shared my table with him when he had nowhere to sit.) After about an hour or so of talking on spiritual matters (having greatly enjoyed our conversation) he made me Assistant Lay Chaplain to the Royal Canadian Navy! A title which, I assume, I hold in perpetuity? Me, of all people. He invited me aboard ship and gave me a tour. The sailors looked like they would have been just as thrilled to keel-haul me. I wish, for the life of me, I could remember his name, but that would have been around 1996.

So, you just reminded me of all that! How happy I am to hear from one of my brethren. :-)

You know, I still haven’t seen that movie, though I feel like I have. I’ve discussed it enough (after having written this post) that I think the whole thing would just irk me to no end. And about Chaucer: The interesting thing about Chaucer is that the Elizabethans didn’t know what to make of him. They didn’t recognize that he was actually writing Iambic Pentameter, not knowing how to read middle English. They re-discovered and re-invented Iambic Pentameter without reference to Chaucer. He was a great poet, they decided, but a poor and rough metrist.

Let me know, if you feel like it, how your students react to the post and the movie.

LikeLike

Thank you, found this very interesting. I’m singing Britten’s setting of this poem next week as part of a presentation of art songs from World War II. Because Britten was a genius for vocal writing the poetic analysis is basically done for me, but it’s good to set the music aside for a few minutes and really look at the poetry. ~Music Major: History Concentration

LikeLike

Hi,

I’m a high school student from NSW, Australia, in my final year, and I am currently comparatively studying Donne’s Holy Sonnet’s with Margaret Edson’s W;t. I’d just like to say, quite simply, that your posts on Donne’s Sonnets have absolutely opened my eyes to the world of poetry. I will not lie, I tended to view the medium of poetry not so much with distaste as with a stagnated interest that would oft lead to a begrudging moan towards the task of studying poetry.

However not only have your posts been efficacious towards my studies, but have stimulated in me an amassed amazement and due respect towards the use and importance of meter (particularly in Donne’s Sonnets), and the contextual necessities in studying and appreciating Elizabethan poetic works.

I also went on to read a few more of your posts and sumptuously enjoyed your presentations and explanations of Plain Poetry. As a work I would’ve have previously viewed with an inadvertent scoff and consternation as to how an audience could consider this ‘poem’ with an awe of greatness, your unravelling of the constructs of Williams’ ‘The Red Wheelbarrow’ left me awestruck and appropriately humbled. I still struggle to grasp, think it humbly silly, as to how that short, to the first glance almost childish, poem had such a great effect on me after enveloping myself in your perceptions of his work.

I have since chagrined myself for my sheer ignorance to the medium of poetry. I can only state my adulation and great thanks to your posts on Donne’s Sonnets and furthermore poetry as a whole, it has truly transformed me.

LikeLike

That’s such high praise I’m not sure how to respond except to say I started out just like you. This: ” I tended to view the medium of poetry not so much with distaste as with a stagnated interest that would oft lead to a begrudging moan towards the task of studying poetry,” was also how I felt about poetry when in high school. The problem, as I see it, is that too few contemporary poets (who do most of the teaching) really know that much about poetry. Sounds hard to believe, but that’s been my experience. You could probably count on one hand the number who understand meter.

All that said, I’m happy you’re enjoying the blog. :-)

Lately I’ve been thinking I’ve run out of topics to talk about, but we’ll see. I’ve been more interested in just writing poetry.

LikeLike

I’m from Norfolk, England (UK). Thank you for your detailed analysis of meter – examiners love it!

LikeLike

Thank you so much for your thorough analysis of meter.

LikeLike

You’re welcome.

LikeLike

Stopped by to look for information/analysis of “God’s Will for You and Me”. Have you had time to do a rhetorical analysis focusing on either ethos/logos/pathos? I’m in need of two outside sources for an analysis I have to write for the English 102 class. Thank you. Tre in Trussville, AL

LikeLike

Hi Tre, I haven’t. Not sure what poem you’re referring to?

LikeLike

Hi there. I’m a mature undergrad student a few weeks from graduating. I’ve been tasked to ‘live with’ this sonnet for the semester, which includes reciting, scanning, and writing two papers. I really appreciate your insights into the metre. I’m in Windsor, Ontario, Canada.

LikeLike

That’s a long time to live with the sonnet. Let me know what comes of it. :)

LikeLike

I’m a Chinese college student. Your analysis is very useful for me. It’s very nice of you to share your understanding. Appreciate that very much!

LikeLike

Thanks, Keisha. :) I’m glad you enjoyed it.

LikeLike

Is it okay to note a solecism?

LikeLike

Why not? There’s a first time for everything.

LikeLike

Also a Chinese college student. It’s wondrous that you are still replying our comments for a post over 10 years ago! I am doing a presentation on John Donne’s poems and I enjoyed your post very much. Thanks :)

LikeLike

Welcome to the site. This website is sort of my “book about poetry”, so to me everything is still current. :) Stay well.

LikeLike

I have found this post so interesting. We’re just starting to read early modern poetry on my certificate in English Literature course (studying with Oxford University in the UK. I was struggling with settling a meter as I read Donne, so decided to see what people had written before I look at the academic secondary sources. Anyway, I found your post very helpful so thank you for writing it!

LikeLike

Thanks for the comment. I always like knowing where commenters are writing from. And glad the post was helpful. :)

LikeLike