- If scansion is new to you, check out my post on the basics.

- February 22, 2009 – If you enjoy Frost, you might like reading Birches along with a color coded scansion of Birches included in my post on Frost’s Mending Wall. To find all the posts I’ve written on Robert Frost, click here.

- After you’ve read up on Robert Frost, take a look at some of my poetry. I’m not half-bad. One of the reasons I write these posts is so that a few readers, interested in meter and rhyme, might want to try out my poetry. Check out Spider, Spider or, if you want modern Iambic Pentameter, try My Bridge is like a Rainbow or Come Out! Take a copy to class if you need an example of Modern Iambic Pentameter. Pass it around if you have friends or relatives interested in this kind of poetry.

- April 23 2009: One Last Request! I love comments. If you’re a student, just leave a comment with the name of your high school or college. It’s interesting to me to see where readers are coming from and why they are reading these posts.

- April 25 2009: Audio of Robert Frost added.

- April 26 2009: Robert Frost’s “For Once, Then, Something.”

- May 5 2009: Robert Frost’s “The Pasture”

- May 24 2009 – Interpreting Robert Frost’s “Stopping by Woods”

- July 21 2009 – New Post Robert Frost’s “Out, Out”

The Road Not Taken

One of the loveliest poems in the English language is Frost’s The Road Not Taken. Part of the magic is in how Frost loosens meter to obtain a more colloquial tone. In one of the most enjoyable books I own (among books on Frost) Lea Newman relates that according to a survey of 18,000 written, recorded  and videotaped responses, this poem (along with Robert Frost) is America’s most popular poem – a probably more accurate poll than the self-selected poll done by poets.org. Lea also writes that Frost’s intent, in writing the poem, was to satirize his friend, Edward Thomas, who would frequently dither over which road he and Frost should walk. (Edward Thomas was an English poet who Frost befriended while living in England). Frost completed and sent the poem to Thomas only after he had returned to New Hampshire. Thomas, however, didn’t read the poem as satire and neither have other readers coming to the poem for the first time.

and videotaped responses, this poem (along with Robert Frost) is America’s most popular poem – a probably more accurate poll than the self-selected poll done by poets.org. Lea also writes that Frost’s intent, in writing the poem, was to satirize his friend, Edward Thomas, who would frequently dither over which road he and Frost should walk. (Edward Thomas was an English poet who Frost befriended while living in England). Frost completed and sent the poem to Thomas only after he had returned to New Hampshire. Thomas, however, didn’t read the poem as satire and neither have other readers coming to the poem for the first time.

I personally have a hard time taking Frost’s claims at face value.

But here he is saying so himself:

- If you don’t see a play button below, just copy and paste the URL and you will be able to hear the recording.

More to the point, the provenance of the poem seems to be in New England – prior to Frost’s friendship with Thomas. Newman references a letter that Frost wrote to Susan Hayes Ward in Plymouth, New Hampshire, February 10, 1912:

Two lonely cross-roads that themselves cross each other I have walked several times this winter without meeting or overtaking so much as a single person on foot or on runners. The practically unbroken condition of both for several days after a snow or a blow proves that neither is much travelled. Judge then how surprised I was the other evening as I came down one to see a man, who to my own unfamiliar eyes and in the dusk looked for all the world like myself, coming down the other, his approach to the point where our paths must intersect being so timed that unless one of us pulled up we must inevitably collide. I felt as if I was going to meet my own image in a slanting mirror. Or say I felt as we slowly converged on the same point with the same noiseless yet laborious stride as if we were two images about to float together with the uncrossing of someone’s eyes. I verily expected to take up or absorb this other self and feel the stronger by the addition for the three-mile journey home. But I didn’t go forward to the touch. I stood still in wonderment and let him pass by; and that, too, with the fatal omission of not trying to find out by a comparison of lives and immediate and remote interests what could have brought us by crossing paths to the same point in a wilderness at the same moment of nightfall. Some purpose I doubt not, if we could but have made out. I like a coincidence almost as well as an incongruity.

[My thanks to Heather Grace Stewart, over at Where the Butterflies Go, for the entire quote.]

About the Poem

The poem is written, nominally, in Iambic Tetrameter. Nominally because Frost elegantly varies the meter to such a degree that readers may only glancingly hear the imposition of a metrical pattern – the effect is one of both metrical freedom and form. I have based my scansion, by the way, on Frost’s own reading of the poem. I suppose that might be considered cheating, but Frost’s own conception of the poem interests me.

- March 28 2011 • Given some time and a conversation with a reader and poet Steven Withrow (see the comments) I’ve changed the scansion of the last stanza to reflect the way Frost probably would have scanned the poem (rather than how he read it). The new scansion, immediately below, retains the tetrameter meter throughout (more on how later). You can still find my old scansion at the bottom of the post. Decide for yourself which scansion makes more sense. As for myself, I lean toward the new scansion. All unmarked feet are iambic and all feet in blue are anapests.

Frost recites The Road not Taken:

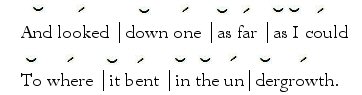

The first element to notice is the rhyme scheme and overall structure of the poem. The poem is really four stanzas, quintains, each having the same rhyme scheme – ABAAB. The nested couplets within the stanzas subliminally focus the ear, while resolution to the pattern is found in the final rhyme. The overall effect of the rhyme scheme is analogous to that of the Petrarchan Sonnet. That is, rather than springing forward, the internal couplets produce the effect of rounded thought and reflection – a rhyme scheme suited to Frost’s deliberative intellect.

The same point I made in my post on Sonnet forms, I’ll make here. In the hands of a skilled poet, rhyming isn’t about being pretty or formal. It’s a powerful technique that can, when well done, subliminally direct the listener or reader’s ear toward patterns of thought and development- reinforcing thought and thematic material. In my own poetry, my blank verse poem Come Out! for example, I’ve tried to exploit rhyme’s capacity to reinforce theme and sound. The free verse poet who abjures rhyme of any sort is missing out.

The first three lines, metrically, are alike. They seem to establish a metrical pattern of two iambic feet, a third anapestic foot, followed by another iambic foot.

The first three lines, metrically, are alike. They seem to establish a metrical pattern of two iambic feet, a third anapestic foot, followed by another iambic foot.

Two roads |diverged |in a yel|low wood

The use of the singular wood, instead of woods, is a more dialectal inflection, setting the tone for the poem with the first line. The third foot surrounded by strong iambs, takes on the flavor of an iambic variant foot.

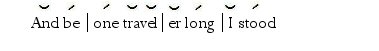

After the first two lines, the third line could almost be read as strictly Iambic.

![]()

This would be an example of what Frost would consider a loose Iamb. If read one way, it’s an anapest, if the word is elided – trav‘ler – it creates an Iambic foot. Although I don’t think it’s deliberate (Frost didn’t go searching for a word that could create a loose Iamb) but the ambiguity subliminally encourages the ear to hear the more normative meter of Iambic Tetremater. Frost will play against and with this ambiguity throughout the poem.

Note: I just found that Frostfriends.org scanned the line as follows:

- ! ! - - - ! - ! And be / one trav el / er long / I stood .........4 feet (iambic) (dactyl) (iambic) (iambic) Converting their symbols - it would look like this:

This is not an unreasonable way to scan the poem – but it ignores how Frost himself read it. And in that respect, and only in that respect, their scansion is wrong. Furthermore, even without Frost’s authority, their reading ignores Iambic meter. Frost puts the emphasis on trav-eler and so does the meter. Their reading also ignores or fails to observe the potential for elision in trav‘ler which, to be honest, is how most of us pronounce the word. A dactyllic reading is a stretch. I think, at best, one might make an argument for the following:

This is not an unreasonable way to scan the poem – but it ignores how Frost himself read it. And in that respect, and only in that respect, their scansion is wrong. Furthermore, even without Frost’s authority, their reading ignores Iambic meter. Frost puts the emphasis on trav-eler and so does the meter. Their reading also ignores or fails to observe the potential for elision in trav‘ler which, to be honest, is how most of us pronounce the word. A dactyllic reading is a stretch. I think, at best, one might make an argument for the following:

If one is going to put the emphasis on one, choosing to ignore the metrical pattern (which one can do), then it seems arbitrary to insist on reading traveler as a three syllable word. If one is going to put a modern interpretive spin on the poem, then I would opt for a trochaic second foot and elide traveler so that the line reads the way most of us would read it.

In the fourth line of the first quintain, Frost allows an anapest in the final foot, offsetting the pattern established in the first two lines. Curiously (and because the other feet are Iambic) the effect is to reinforce the Iambic Tetrameter patter. There is only one line that might be read as Iambic, but because the other feet, when they aren’t variant anapests, are Iambic, Frost establishes Iambic Tetrameter as the basic pattern. The final line of the quintain returns the anapestic variant foot but, by now, Frost has varied the lines enough so that we don’t hear this as a consistent pattern.

It’s worth noting that, if Frost had wanted to, he could have regularized the lines.

And looked |down one |far as |I could

To where |it bent |in un|dergrowth

Compare the sound of these regularized lines to what Frost wrote and you might begin to sense how the variant feet contribute to the colloquial tone of the poem. Regularizing the lines, to my ear, takes some of the color from the poem. The anapests encourage the reader to pause and consider, reinforcing the deliberative tone of the poem – much as the rhyme scheme. It’s the play against the more regularized meter that makes this poem work. As I’ve written elsewhere, a masterfully written metrical poem has two stories to tell – two tales: one in its words; the other in its meter. The meter of The Road Not Taken tells a story of pause and consideration. Its an effect that free verse poetry can approximate but can’t reproduce, having no meter to play against.

The second quintain’s line continues the metrical pattern of the first lines but soon veers away. In the second and third line of the quintain, the anapest variant foot occurs in the second foot. The fourth line is one of only three lines that is unambiguously Iambic Tetrameter. Interestingly, this strongly regular line comes immediately after a line containing two anapestic variant feet. One could speculate that after varying the meter with two anapestic feet, Frost wanted to firmly re-establish the basic Iambic Tetrameter pattern from which the overal meter springs and varies.

The second quintain’s line continues the metrical pattern of the first lines but soon veers away. In the second and third line of the quintain, the anapest variant foot occurs in the second foot. The fourth line is one of only three lines that is unambiguously Iambic Tetrameter. Interestingly, this strongly regular line comes immediately after a line containing two anapestic variant feet. One could speculate that after varying the meter with two anapestic feet, Frost wanted to firmly re-establish the basic Iambic Tetrameter pattern from which the overal meter springs and varies.

What’s worth noting, as well, is how beautifully Frost manages a colloquial expressiveness in this poem with expressions like having perhaps, Though as for that, really about. After setting the location in the first quintain, the self-reflective expressions, new to poetry up to this point, create a feeling of shifting ideas and thought, of re-consideration within the poem itself – as if the speaker were in conversation with himself and another. Colloquial, in fact, is “considered to be characteristic of or only appropriate for casual, ordinary, familiar, or informal conversation rather than formal speech or writing.” It’s an effect that has been touched on by other poets, but never with such mastery or understanding as Frost demonstrates. Expressions like better claim , wanted wear and the passing there add a New England dialectal feel to the lines.

Again, it’s worth noting the Frost probably could have regularized the lines, but he might have had to sacrifice some of the colloquial feel reinforced by the variant anapestic feet that give pause to the march of an iambic line.

Then took |the o|ther road |as fair,

Having |perhaps |the bet|ter claim,

Because |of grass |and wan|ting wear;

Though as |for that |the pas|sing there

Had worn |them just |about |the same.

Notice how, at least to my ear, this metrically regularized version looses much of its colloquial tone.

On the other hand, here’s a free verse, rhyming version:

Then I took the other as being just as fair,

And as maybe having a better claim,

Because it was overgrown with grass and wanted wear;

But the passing there

Had really worn them just about the same.

Curiously, even though this is closer to spoken English (or how we might expect the average person to deliberate) the poem loses some of its pungent colloquial effect. And here it is without the rhyme:

Then I decided the other road was just as nice

And was maybe even better

Because it was overgrown with grass and needed

to be walked on; but other people

Had just about worn them the same.

And this, ultimately, is modern English. This is the speech of real people. But there’s something missing – at least to my ear. Free verse poets, historically, have claimed that only free verse can capture the language of the times. I don’t buy it. To me, this last version sounds less colloquial and speech-like than Frost’s version. My own philosophy is that great art mimics nature through artifice, or as Shakespeare put it in Winter’s Tale:

Yet nature is made better by no mean

But nature makes that mean: so, over that art

Which you say adds to nature, is an art

That nature makes. You see, sweet maid, we marry

A gentler scion to the wildest stock,

And make conceive a bark of baser kind

By bud of nobler race: this is an art

Which does mend nature, change it rather, but

The art itself is nature.

In the third quatrain, the first line can be read as a loose Iamb if we elide equally to read equ‘ly – making the line Iambic Tetrameter while the second is solidly so.

After two more regular lines, Frost once again diverges from the pattern. The third and fifth lines are pentasyllabic though still tetrameter, each line having two anapests. Interestingly, as with the second quintain, Frost never seems to vary too far from the pattern without reaffirming the basic meter either before or after the variant lines. The interjection Oh is entirely unnecessary strictly in terms of the poem’s subject matter. Lesser poets writing meter might have omitted this as an unnecessary variant, but the word heightens the colloquial feel of the poem and is very much in keeping with the poem’s overall tone and them – echoed in the first line of the final quintain – a sigh.

The second and fourth lines are actually Iambic Trimeter, but once again Frost reaffirms the meter from which they vary by placing a solidly Iambic Tetrameter line between them (the fourth line).

- March 28 2011 • The reading above is my original scansion. This scansion was based on the way Frost read it. The problem with scanning it that way is twofold: First, it breaks the tetrameter pattern, which isn’t unheard of, but very unusual for Frost; Second, it means the rhyme between hence and difference is what’s called an imperfect rhyme. An imperfect rhyme is when the syllables are nominally the same but one syllable is stressed and the other is unstressed. In the scansion above, hence is stressed and the –ence ending of diff‘rence is un-stressed. Emily Dickinson lovedthis kind of rhyme but Frost, rarely if ever. The problem is that Frost wants his cake and eats it too. To my ear, when I listen to him read the poem, he reads the last rhyme as an off-rhyme. But, like the Elizabethans, he probably would have scanned it as below:

Two things to notice: In the second line I’ve read the first foot as headless. This is a standard variant foot that can be found with the Elizabethans. Some call it anacrusis. A headless foot means that the first syllable of the foot is missing. Second, the last line is changed so that difference, at least on paper, is pronounced trisyllabically as diff/er/ence, rather than diff’rence. This makes the line tetrameter and makes the final rhyme a perfect rhyme.

Frost sometimes took criticism from more strictly “Formalist” poets (including his students) who felt that his variants went too far and were too frequent. In either case, whether you can it the way Frost read it or according to the underlying meter and rhyme scheme, Frost’s metrical genius lay preciely in his willingness to play against regularity. Many of his more striking colloquial and dailectal effects rely on it.

- Below is the original scansion: Anapests are blueish and feminine endings are green.

- If you prefer this scansion (I no longer do), then not only does Frost vary the metrical foot but the entire line. Even so, the two Iambic Trimeter lines (the second and last lines of the quintain) are octasyllabic. No matter how they’re scanned, they don’t vary from the octasyllablic Iambic Tetrameter as they might. The anapests elegantly vary the final lines, reinforcing the colloquial tone – even without dialectal or colloquial phrasing.

Newman quotes Frost, saying:

“You can go along over these rhymes just as if you didn’t know that they were there.” This was a poem “that talks past the rhymes,” he said, and he took it as a compliment when his readers told him they could hear him talking in it.

What Newman and Frost neglect to mention is how the meter of the poem amplifies the sense of “talking”. Frost’s use of meter was part and parcel of his genius – and the greatness of his poetry.

If this was helpful and if you enjoyed the post, let me know. Comment!

Pingback: Rhyme & Meter On-line: Sunday February 15 2009 « PoemShape

can i copy this for my classroom report?

LikeLike

If you want to use this post as a reference, sure. I write these posts for everyone.

LikeLike

Can you please scan Frost’s “New Hampshire”?? How does the “sound of sense” prevail within the iambic structure in that poem?

LikeLike

I’ll consider your request. :) That’s a long poem though.

LikeLike

I am a student of english literature and from Pakistan.

Your this outstanding Labour is playing a too much role. It is a very very very very very very very helpful for students

LikeLike

So glad you commented, Nagina. I wish you all the best in Pakistan. Feel free to write me any time. :)

LikeLike

this poem is cool i have to write a 2000 word about it how it inspires me

LikeLike

you wrote: “Frost sometimes took criticism from more strictly “Formalist” poets (including his students) who felt that his variants went too far and were too frequent. But Frost’s metrical genius lay preciely in his willingness to play against regularity”

and THAT has made all the difference. In his writing and, I hope, in mine.

Thanks so much for your incredibly thoughtful essays, and for allowing me to help out with the quote in this one.

Cheers

Heather

LikeLike

Rhyming….who do we know that does this ;D

LikeLike

Fantastic, excellent and many other words which have positive connotations! This was an immense help and possibly the best sight out there for info on poems and scansions.

Thanks!

LikeLike

Wow, Nari, thank you. : )

LikeLike

Thank you for your in depth study of this poem. I am taking a literature class at college in VA and have to write a paper on “The Road Not Traveled”. This was incredibly helpful! You have been cited :)

LikeLike

Well… I might not be a “published author”, but I’m a “cited author”. : )

LikeLike

Than you very much for all this work. I am taking English 102 at Liberty University and I am have alot of trouble with this poem. You really broke it down and it was a great help!

LikeLike

Thanks John! I’m going see if I can find some images from Liberty Univversity. It’s always interesting see where folks are writing from.

LikeLike

Hi,

I’m student from Rostock, Germany and currentliy preparing for my final oral exams in English. I chose amongst other subject the poems of Robert Frost for one part. Your analysis is very helpful to the understanding of the poem. I haven’t had the time to read your entire article, so this may be saying something you already said: but looking at your colored scanning I can’t but help see that the main stress of each line with an anapest lies directly before it.

What do you think about reading the line “Because it was grassy and wanted wear” as

“BeCAUSE|| it was|| GRASSy’n|| WANted|| WEAR.”

LikeLike

The thing to know about meter is that it springs from a convention.

Think of it this way: Meter is like the framing of a modern house (though in Germany everything is built with concrete blocks – for the most part). In America, most modern framing consists of studs at two foot centers (the center of each stud measures two feet from the next). On that basic framework, an infinite variety of walls can be built. Putting windows into your wall will vary the spacing of the studs – just as variant feet will vary meter’s basic pattern. Scansion is meant to illustrate a poem’s regular stress patterns (and variants from that pattern).

In the case of “The Road Not Taken”, the basic pattern or meter of the poem most easily fits an iambic meter because most of the feet can be comfortably read as iambic.

Because none of Frost’s variant feet occur in any regular pattern, we can reasonably assume that the basic pattern is Iambic Tetrameter, or four iambic feet per line. This is the basic pattern from which he is varying.

So, with that in mind, the first thing to do is to mark as many Iambic Feet as you can. Scansion is not meant to illustrate how a reader might read a poem (which is how you have sensibly scanned the line), but is meant to reveal how a poet works with and against a regular pattern. In the case of The Road Not Taken, once you have marked off the Iambic Feet (which reflects the basic pattern) the feet which remain are anapestic. So (and I know I’m repeating myself) scansion is all about identifying the regular metrical pattern of a poem and how it may or may not vary from that pattern, not how a reader might be expected to read a poem.

Does this help?

LikeLike

Hello, another day, it is cold and wet here, hopefully, tomorrow is great or better.

LikeLike

Outstanding!!! i cannot agree more… for there is a saying “you can never put a good man down, for life will always be a climb, no matter how steep it is, the important thing is you keep on going until you reach that light at the end of the tunnel, for only god knows what is in store for your future…

LikeLike

this is really a very nice poem. i never fail to appreciate it every time i read it. it reminds me that in life we always have to make choices and you’ll never know what your ch0ices meant when you try to follow a road and see its outcome later on….

LikeLike

I always find that it’s the simplest poems can convey the greatest complexity. As the proverb has it: Smooth waters run deep.

LikeLike

Hi! So glad to see I’m not the only Liberty student who sought help and found you! Thanks, it was great to get confirmation that I am actually understanding what I’m doing! I started looking for some help and your page has helped me realize I am getting this! Wow! Thanks and as stated above, you’ll be cited! Have a great day, you just made mine!

LikeLike

That’s really cool. Thanks for letting me know where you’re writing from. Maybe I should teach poetry at Liberty?

LikeLike

Thank you so much for helping me to understand scansion, meter, foot, iambic, etc., better. My brain is still awash in all of these terms, but I am better able to pick out what I want to say from your post. I am also a student at Liberty University in the Distance Learning Program. I will be citing you in my essay and again, thank you for your assistance. I am most grateful.

LikeLike

So glad to help. If you or any other students ever see ways to improve, let me know.

LikeLike

Pingback: Week Five | Pages of Books

omigoodness, what a wealth of information and I can study all the forms too! Thank you. I’m always looking this kind of stuff up.

LikeLike

Hi Joy, nice to see you again. :-)

LikeLike

Just discovered this blog –and I’ll surely be a regular visitor here. Thanks!

I’m not certain that Frost deviates from the dominant tetrameter pattern in the final stanza.

Even while hearing Frost read it, I conclude that the second line opens with a catalectic iambic foot (“Some”), giving the line its first stressed syllable (though it is lighter than the subsequent three stresses). After all, we typically stress the first syllable in “somewhere” — which is akin to the first foot of “Something there is that doesn’t love a wall.” The rest of line 2, to my ear, moves to an iamb (“where a-“), to an anapest (“-ges and a-“), to an iamb (“-ges hence”).

In the final line, I also hear four feet: an iamb (“And that”), a rising anapest with a heavier second syllable (“has made all”), an iamb (“the dif-“), and a final iamb that, wonderfully, is lighter than the iamb that precedes it, giving the poem a literal “down ending.” If we don’t give the final syllable a little stress and admit that the “er” sound in “difference” holds the slightest of weight and duration (it’s not merely “diff’rence”), then we can’t really say that the “hence” rhyme in line 2 resolves properly. For Frost, as for most metrical poets, rhyme is a condition between two stressed syllables, and if we leave the last syllable unstressed, we not only lose the beautiful four-beat pattern of the entire poem but we also negate that final “dropping off” rhyme.

What do you think?

LikeLike

Glad to hear that. I haven’t been contributing as much, lately, working on a separate literary project, but hopefully posts will pick up again.

The term “catalectic” generally refers to the final foot of a metrical line. I think you mean to read that second line as having a headless foot (some refer to it as anacrusis). So, you’re reading the line as follows:

^ Some| where ag|es and ag|es hence

I think that’s a perfectly good reading. Nowadays, I might even lean that direction and agree with you. I scanned it the way, to me, Frost read it, which may not be how he metrically imagined the line.

Here’s how you read the last line:

And that| has made all| the diff|erence

I have no argument with that. And, with some distance, I side with you. Metrically speaking, this is probably how Frost would have scanned the line. You’re also right to argue for the rhyme. That being said, Frost reads the line as though they were trimeter, at least to my ear.

At this point, and for the record, I’m with you. I should probably offer a new scansion to reflect that.

LikeLike

One clarification: If the final foot of the poem were intended to be an amphibrach or feminine ending, as you suggest, then Frost would have been obliged to set up his final rhyme with a rhyme, three lines earlier, for “diff-” — and not for “-ence” as he does. It seems clear to me that he wants “-ence” to receive slightly more stress than “er” (which is clipped though not completely elided) and less stress than “diff-“.

A true “feminine ending” is confirmed by noting like sounds in the stressed syllables, so “button” and “flutter” could be called feminine rhymes. There are all manner of pararhymes, of course, but Frost does not seem to be playing with those in this poem.

Shifting from tetratmeter to trimeter in two lines of the last stanza — not to mention using an amphibrach to end the poem — is harder to swallow, for me, than the metric explanation I give above.

But Frost does leave room for ambiguities.

LikeLike

Your right about “anacrusis” being the more accurate term, but I’ve heard “catalexis” used in this context as well. Thanks!

LikeLike

You’re right about “anacrusis” being the more accurate term, but I’ve heard “catalexis” used in this context as well. Thanks!

LikeLike

interesting read. imma student in california but im in turkey right now

LikeLike

Pingback: Week Three | Pages of Books

Pingback: Poem: The Road Not Taken by Robert Frost « Inspiring My Life

cool read

LikeLike

UPINVERMONT, thank you for this informative essay, it has been the most helpful and insightful page I’ve found yet discussing this great poem.

LikeLike

Thanks Anon. :-) Glad you found it helpful.

LikeLike

Thanks for the lesson on scansion, and the audio. This page has really helped me get a start in understanding the poem’s structure. Any chance the you could tell us where you found the audio? I’d like to get a little closer to the source and possibly discover more. I’m a student at Austin Community College.

LikeLike

Thanks j.j., you can find the source of the audio here. I’ve been in and around Austin Community College, but that was a few years ago. :-)

LikeLike

Thank you so much for all your information about The Road Not Taken by Robert Frost ;) I had some troubles with it but now it’s totally clear to me!!! I study English and American Studies in Austria and I have to write an essay about the poem in my Introduction to Literature class – for a non english native speaker it is much harder :D

LikeLike

You’re welcome, Lisa. :-) When I read Goethe or Rilke auf Deutsch, it’s the same for me, sometimes even the simplest poems.

LikeLike

Hi! You’re #4 in my list of scholarly articles! I’m writing a comparison and contrast essay about about “The Road Not Taken” and “I Used to Live Here Once” by Jean Rhys. I’m a student at Ashford University, and think your content is both intellectual and well-communicated.

LikeLike

Thanks Angie. :-) Glad you approve. I’ve read good things about Clinton, Iowa, but have never been. Are the leaves out? And good luck with your essay.

LikeLike

momentous decision was made by frost in 1912

LikeLike

thanking to this site in advance,

hiii,,, i’m ESL student, I study English literature in Indonesia. analyzing poem is my first assignment, and i hope my decision to choose THE ROAD NOT TAKEN as my poet analysis in case of Rhyme and meter. in addition, the essay above is helpful which i consider as one of my reference…

LikeLike

Welcome Siti. It’s a snowy, cold and wintrish morning up here in Vermont. It must be warm in Indonesia. :-)

LikeLike

Hey, I’m Ruhee, from the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay. I’m taking a humanities course called Reading Literature, my first deviation from my major, which is Chemistry. Your post was very helpful, because though I love to read I usually have a really hard time interpreting poetry and especially trying to get the metrical structure, because of the differences in pronunciation in Indian and American English.

LikeLike

Thanks Ruhee. That’s cool that you’re studying Chemistry — requires convergent thinking, and not something that I was good at. In Chemistry (at least as I studied it) one frequently has assess any number of possibilities and narrow them down to one rule. Analyzing poetry takes divergent thinking — taking a single text and from it sorting out any number of possible interpretations.

The difference in pronunciation is an interesting question though. Since most metrical poetry was written in England, I would expect Indian English, in fact, to be closer. Robert Frost, I suppose, would be the exception to that. :-)

LikeLike

Thanks. This is of great help.

LikeLike

What are the half ryhmes?

LikeLike

Who said anything about half rhymes?

LikeLike

No one said anything about them. I just want to know what are the half rhymes in this poem (-: I found them anyways, thanks!

LikeLike

Pingback: Why do poets use iambic pentameter? | How my heart speaks

Pingback: Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening | How my heart speaks

I don’t know if you still even use this page considering it’s about 10 years old, but I’ve been writing an essay in PA about Robert Frost and your scansions and explanations have really helped me a lot. My essay is solely about his use of meter in his poetry and I needed about 5 examples. I have also cited you in my paper. Thank you so much!!!

LikeLike

I sure do. Glad it helped you. :)

LikeLike

There’s a very little chance you’ll see this, but if you do thank you in advance.

How do you know where one foot ends in 1 line of a poem?

Like for example in Robert Frost’s poem, stopping by the woods on a snowy evening, I know that it’s iambic tetrameter, so it goes something like:

Whose woods | these are | I think | I know.

The problem is I don’t how you can tell where to separate each foot, if your given a random poem and you don’t know what type it is, but you do know where the syllables are stressed and unstressed. Hopefully you understand my question.Have s nice day :))

LikeLike

Hi Dorothy, I’m the eye of Sauron. I see every comment. :)

Let’s answer your questions—or try.

//How do you know where one foot ends in 1 line of a poem?//

If the poem is metrical, then there will be a metrical pattern. The pattern, like Iambic Pentameter, or Emily Dickinson’s alternating hymn meter, will dictate how many feet are in the line. That won’t tell you whether this or that foot is a variant foot, but knowing the pattern will help you decide which feet are variant. In other words, if you have 11 syllables in what should be a ten syllable line of Iambic Pentameter, then one of the feet has to have an extra syllable which means it’s either probably an anapest or an amphibrach (which is nearly always the final foot—or, as it’s called, a feminine foot).

//The problem is I don’t how you can tell where to separate each foot, if your given a random poem and you don’t know what type it is…//

So, meter is really the ghost of music’s time signature. As far as historians can tell, all poetry began as song lyrics. So all poetry, as far as we know, was sung to a beat. They were lyrics. In China, many poems were written to the tune of this or that song. This meant that the poets had to, essentially, write their lyrics to an imagined and regular beat. Meter was born. So, figuring out the meter of the poem is like figuring out the time signature of a piece of music. Is the music 4/4, 3/4, 6/8? Knowing the time signature means you could divide the music into measures. A measure of music and a foot in poetry are, in some sense, the same. Knowing the musical beat in music, and knowing the stress pattern in a line of poetry, allows you to divide it up into measures or feet respectively. For example:

If you go to the house by the quay

Buy a fig at the store on the way

The stressed words (or beat) would be:

If you go to the house by the quay

Buy a fig at the store on the way

Which would make the meter anapestic:

If you go| to the house| by the quay

Buy a fig| at the store| on the way

Similarly:

Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow

Creeps on this petty pace from day to day

Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow

Creeps on this petty pace from day to day

Which would be:

Tomor|row and| tomor|row and| tomorrow

Creeps on| this pet|ty pace| from day| to day

Notice that the last foot of the first line above is a feminine foot. We know this because the lines are Iambic Pentameter, that there are only 5 feet or measures in an iambic pentameter line, and that in order for there to be only five feet, the last foot must be a variant foot. I’ve written a post on Iambic Pentameter in variant feet. Let me know if you can’t find it.

LikeLike

Thanks so much for the help! This is a big help for my English meter presentation, in which i will be analyzing your poem “November” btw and comparing it to Robert Frost’s poem “The Road Not Taken” :)

LikeLike

You’re welcome! I noticed, though, that I made a mistake (which I just corrected). My excuse is that I was rushing out the door this morning. I wrote that an Iambic Pentameter line has ten feet. It doesn’t. I meant to write (should have writen) five feet.

And comparing my poem to Frost’s! I don’t know whether to be flattered or to run and hide.

Well, as far as November goes, the poet is still living (for the time being). If you want to ask me any questions, just ask.

LikeLike

There are some nice observations here.

I do hear a couple of lines differently.

To me, in Frost’s reading of the second line, the 2nd beat clearly lands on “could”:

and SOrry i COULD not TRAvel BOTH

And I hear the first line of the last stanza as headless, and with the beat on “this” instead of “with:

I shall be TElling THIS with a SIGH

In this reading, we hear two consecutive headless lines, and “I” rhymes with “sigh”.

Whenever I used to read it to myself, I too placed the beat on “with”, but hearing Frost, I prefer his delivery of this line: it sounds more considered.

Though his voice is expressive in its own way, there isn’t great variation of pitch in his voice, which I suppose might make the beats harder to identify. Nonetheless, the beat placements sounded very clear to me.

LikeLike

I can hear those lines the way you did, but also the way I originally scanned them, which I still prefer. Knowing that meter mattered to Frost and that he took great pride in his mastery of it, and that he also (I think) coined the term “loose iambs” when referring to anapests (for instance) I went on the assumption that that’s what he was writing and how he would have considered the variant feet. If, on the other hand, you start introducing amphibrach’s and cretic feet, then my feeling is that a such a scansion would probably run counter Frost’s own conception of the meter. That said, you can still read it that way. There’s no rule saying one has to scan the poem the way the poet read it (or according to a poet’s metrical theories). The scansion above is just my own informed speculation as to what Frost might have intended (or how he might have imagined the poem).

LikeLike

No amphibrachs or cretics in my scansion, Patrick! I would place the foot divisions after each beat:

and SO / rry i COULD / not TRA / vel BOTH

_ I / shall be TE / lling THIS / with a SIGH

A 2nd foot anapest in the first line; a headless beat followed by a 2nd foot anapest, and a 4th foot anapest, in the 2nd line.

One could scan the second line as containing an opening trochee, but in the context of the poem as a whole, marking it as a headless beat followed by an anapest makes more sense to me.

LikeLike

Fair enough. One can certainly hear and scan it that way.

LikeLike

With the beat placement as I hear it in the second line, the anapest wobbles back and forth throughout the stanza, landing in feet 3, 2, 3, 4 & 3 in each of the five lines respectively.

LikeLike

Hi from a student from University of Gävle in Sweden. This has been an extremely good help with my assignment for American Literature.

LikeLike

Thanks for writing! Your comment inspired me to take a tour of Gävle via Google Earth. I’m at 23 Södra Köpmangaten right now. It’s like a little village within the city.

LikeLike