Emily Dickinson possessed a genius for figurative language and thought. Whenever I read her, I’m left with the impression of a woman who was impish, insightful, impatient, passionate and confident of her own genius. Some scholars portray her as being a revolutionary who rejected (with a capital R) the stock forms and meters of her day.

Emily Dickinson possessed a genius for figurative language and thought. Whenever I read her, I’m left with the impression of a woman who was impish, insightful, impatient, passionate and confident of her own genius. Some scholars portray her as being a revolutionary who rejected (with a capital R) the stock forms and meters of her day.

My own view is that Dickinson didn’t exactly “reject” the forms and meter. She wasn’t out to be a revolutionary. She was impish and brilliant. Like Shakespeare, she delighted in subverting conventions and turning expectations upside down.This was part and parcel of her expressive medium. She exploited the conventions and expectations of the day, she didn’t reject them.

The idea that she was a revolutionary rejecting the tired prerequisites of form and meter certainly flatters the vanity of contemporary free verse proponents (poets and critics) but I don’t find it a convincing characterization. The irony is that if she were writing today, just as she wrote then, her poetry would probably be just as rejected by a generation steeped in the tired expectations and conventions of free verse.

The common meters of the hymn and ballad simply and perfectly suited her expressive genius. Chopin didn’t “reject” symphonies, Operas, Oratorios, Concertos, or Chamber Music, etc… his genius was for the piano. Similarly, Dickinson’s genius found a congenial outlet in the short, succinct stanzas of common meter.

The fact that she was a woman and her refusal to conform to the conventions of the day made recognition difficult (I sympathize with that). My read is that Dickinson didn’t have the patience for pursuing fame. She wanted to write poetry just the way she wanted and if fame mitigated that, then fame be damned. She effectively secluded herself and poured forth poems with a profligacy bordering on hypographia. If you want a fairly succinct on-line biography of Dickinson, I enjoyed Barnes & Noble’s SparkNotes.

The Meters of Emily Dickinson

Dickinson used various hymn and ballad meters.

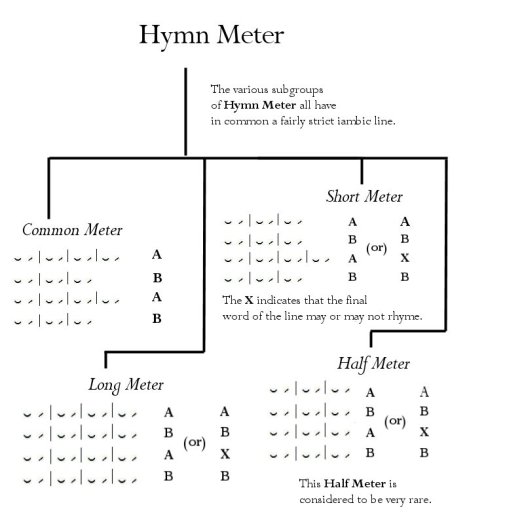

Searching on-line, there seems to be some confusion of terms or at the least their usage seems confusing to me. So, to try to make sense of it, I’ve done up a meter tree.

The term Hymn Meter embraces many of the meters in which Dickinson wrote her poems and the tree above represents only the basic four types.

If the symbols used in this tree don’t make sense to you, visit my post on Iambic Pentameter (Basics). If they do make sense to you, then you will notice that there are no Iambic Pentameter lines in any of the Hymn Meters. They either alternate between Iambic Tetrameter and Iambic Trimeter or are wholly in one or the other line length. This is why Dickinson never wrote Iambic Pentameter. The meter wasn’t part of the pallet.

Common Meter (an iambic subset of Hymn Meter and most common) is the meter of Amazing Grace, and Christmas Carol.

And then there is Ballad Meter – which is a variant of Hymn Meter.

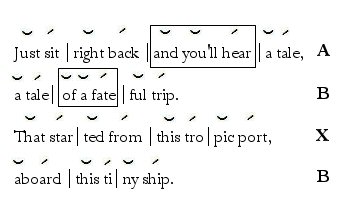

I’ve noticed that some on-line sites conflate Hymn Meter and Ballad Meter. But there is a difference. Ballad Meter is less formal and more conversational in tone than Hymn Meter, and Ballad Meter isn’t as metrically strict, meaning that not all of its feet may be iambic. The best example I have found is the theme song to Gilligan’s Island:

Obviously the tone is conversational but, more importantly, notice the anapests. The stanza has the same number of feet as Common Meter, but the feet themselves vary from the iambic regularity of Common Meter. Also notice the rhyme scheme. Only the second & fourth line rhyme. Common Meter requires a regular ABAB rhyme scheme. The tone, the rhyme scheme, and the varied meter distinguish Ballad Meter from Common Meter.

For the sake of thoroughness, the following gives an idea of the many variations on the four basic categories of Hymn meter. Click on the image if you want to visit the website from which the image comes (hopefully link rot won’t set it). Examples of the various meters are provided there.

If you look at the table above, you will notice that many of the hymn and ballad meters don’t even have names, they are simply referred to by the number of syllables in each line. Explore the site from which this table is drawn. It’s an excellent resource if you want to familiarize yourself with the various hymn and ballad meters Dickinson would have heard and been familiar with – and which she herself used. Note the Common Particular Meter, Short Particular Meter and Long Particular Meter at the top right. These names reflect the number of syllables per line you will frequently find in Dickinson’s poetry. Following is an example of Common Particular Meter. The first stanza comes from around 1830 – by J. Leavitte, the year of Dickinson’s Birth. This stuff was in the air. The second example is the first stanza from Dickinson’s poem numbered 313. The two columns on the right represent, first, the number of syllables per line and, second, the rhyme scheme.

Short Particular Meter is the reverse of this. That is, its syllable count is as follows: 6,6,8,6,6,8 – the rhyme scheme may vary. Long Particular Meter is 8,8,8,8,8,8 – Iambic Tetrameter through and through – the rhyme schemes may vary ABABCC, AABCCB, etc…

The purpose of all this is to demonstrate the many metrical patterns Dickinson was exposed to – most likely during church services. The singing of hymns, by the way, was not always a feature of Christian worship. It was Isaac Watts, during the late 17th Century, who wedded the meter of Folk Song and Ballad to scripture. An example of a hymn by Watts, written in common meter, would be Hymn 105, which begins (I’ve divided the first stanza into feet):

Nor eye |hath seen, |nor ear |hath heard,

Nor sense |nor rea|son known,

What joys |the Fa|ther hath |prepared

For those |that love |the Son.

But the good Spirit of the Lord

Reveals a heav’n to come;

The beams of glory in his word

Allure and guide us home.

Though Watts’ creation of hymns based on scripture were highly controversial, rejected by some churches and  adopted by others, one of the church’s that fully adopted Watts’ hymns was the The First Church of Amherst, Massachusetts, where Dickinson from girlhood on, worshiped. She would have been repeatedly exposed to Samuel Worcester’s edition of Watts’s hymns, The Psalms and Spiritual Songs where the variety of hymn forms were spelled out and demonstrated. While scholars credit Dickinson as the first to use slant rhyme to full advantage, Watts himself was no stranger to slant rhyme, as can be seen in the example above. In fact, many of Dickinson’s “innovations” were culled from prior examples. Domhnall Mitchell, in the notes of his book Measures of Possiblity emphasizes the cornucopia of hymn meters she would have been exposed to:

adopted by others, one of the church’s that fully adopted Watts’ hymns was the The First Church of Amherst, Massachusetts, where Dickinson from girlhood on, worshiped. She would have been repeatedly exposed to Samuel Worcester’s edition of Watts’s hymns, The Psalms and Spiritual Songs where the variety of hymn forms were spelled out and demonstrated. While scholars credit Dickinson as the first to use slant rhyme to full advantage, Watts himself was no stranger to slant rhyme, as can be seen in the example above. In fact, many of Dickinson’s “innovations” were culled from prior examples. Domhnall Mitchell, in the notes of his book Measures of Possiblity emphasizes the cornucopia of hymn meters she would have been exposed to:

One more variation on ballad meter would be fourteeners. Fourteeners essentially combine the Iambic Tetrameter and Trimeter alternation into one line. The Yellow Rose of Texas would be an example (and is a tune to which many of Dickinson’s poems can be sung).

According to my edition of Dickinson’s poems, edited by Thomas H. Johnson, these are the first four lines (the poem is much longer) of the first poem Emily Dickinson wrote. Examples of the form can be found as far back as George Gascoigne – a 16th Century English Poet who preceded Shakespeare. If one divides the lines up, one finds the ballad meter hidden within:

According to my edition of Dickinson’s poems, edited by Thomas H. Johnson, these are the first four lines (the poem is much longer) of the first poem Emily Dickinson wrote. Examples of the form can be found as far back as George Gascoigne – a 16th Century English Poet who preceded Shakespeare. If one divides the lines up, one finds the ballad meter hidden within:

Oh the Earth was made for lovers

for damsel, and hopeless swain

For sighing, and gentle whispering,

and unity made of twain

All things do go a courting

in earth, or sea, or air,

God hath made nothing single

but thee in His world so fair!

How to Identify the Meter

The thing to remember is that although Dickinson wrote no Iambic Pentameter, Hymn Meters are all Iambic and Ballad Meters vary not in the number of metrical feet but in the kind of foot. Instead of Iambs, Dickinson may substitue an anapestic foot or a dactyllic foot.

So, if you’re out to find out what meter Dickinson used for a given poem. Here’s the method I would use. First I would count the syllables in each line. In the Dickinson’s famous poem above, all the stanzas but one could either be Common Meter or Ballad Meter. Both these meters share the same 8,6,8,6 syllabic line count – Iambic Tetrameter alternating with Iambic Trimeter. (See the Hymn Meter Tree.)

Next, I would check the rhyme scheme. For simplicity’s sake, I labeled all the words which weren’t rhyming, as X. If the one syllabically varying verse didn’t suggest ballad meter, then the rhyme scheme certainly would. This isn’t Common Meter. This is Ballad Meter. Common Meter keeps a much stricter rhyme scheme. The second stanza’s rhyme, away/civility is an eye rhyme. The third stanza appears to dispense with rhyme altogether although I suppose that one should, for the sake of propriety, consider ring/run a consonant rhyme. It’s borderline – even by modern day standards. Chill/tulle would be a slant rhyme. The final rhyme, day/eternity would be another eye rhyme.

It occurs to me add a note on rhyming, since Dickinson used a variety of rhymes (more concerned with the perfect word than the perfect rhyme). This table is inspired by a Glossary of Rhymes by Alberto Rios with some additions of my own. I’ve altered it with examples drawn from Dickinson’s own poetry – as far as possible. The poem’s number is listed first followed by the rhymes. The numbering is based on The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson edited by Thomas H. Johnson.

![]()

RHYMES DEFINED BY NATURE OF SIMILARITY

perfect rhyme, true rhyme, full rhyme

- 1056 June/moon

imperfect rhyme, slant rhyme, half rhyme, approximate rhyme, near rhyme, off rhyme, oblique rhyme

- 756 prayer/despair

123 air/cigar

744 astir/door

augmented rhyme – A sort of extension of slant rhyme. A rhyme in which the rhyme is extended by a consonant.bray/brave grow/sown

- (Interestingly, this isn’t a type of rhyme Dickinson ever used, either because she was unaware of it or simply considered it a rhyme “too far”.)

diminished rhyme – This is the reverse of an augmented rhyme. brave/day blown/sow stained/rain

- (Again, this isn’t a technique Dickinson ever uses.)

unstressed rhyme – Rhymes which fall on the unstressed syllable (much less common in Dickinson).

- 345 very/sorry

1601 forgiven/hidden prison/heaven

eye rhyme – These generally reflect historical changes in pronunciation. Some poets (knowing that some of these older rhymes no longer rhyme) nevertheless continue to use them in the name of convention and convenience.

- 712 day/eternity (See Above)

94 among/along

311 Queen/been

580 prove/Love

identical “rhyme” – Which really isn’t a rhyme but is used as such.

- 1473

Pausing in Front of our Palsied Faces

Time compassion took –

Arks of Reprieve he offered us –

Ararats – we took –

- 130 partake/take

rich rhyme – Words or syllables that are Homonyms.

- 130 belief/leaf

assonant rhyme – When only the vowel sounds rhyme.

- 1348 Eyes/Paradise

consonant rhyme, para rhyme – When the consonants match.

- 744 heal/hell

889 hair/here

feminine para rhyme – A two syllable para rhyme or consonant rhyme.

scarce rhyme – Not really a true category, in my opinion, since there is no difference between a scarce rhyme and any other rhyme except that the words being rhymed have few options. But, since academia is all about hair-splitting, I looked and looked and found these:

- 738 guess/Rhinoceros (slant rhyme)

1440 Mortality/Fidelity (extended rhyme)

813 Girls/Curls (true rhyme)

macaronic rhyme – When words of different languages rhyme. (This one made me sweat. Dickinson’s world was her room, it seems, which doesn’t expose one to a lot of foreign languages. But I found one! As far as I know, the first one on the Internet, at least, to find it!)

- 313 see/me/Sabachthani (Google it if you’re curious.)

trailing rhyme – Where the first syllable of a two syllable word rhymes (or the first word of a two-word rhyme rhymes). ring/finger scout/doubter

- (These examples aren’t from Dickinson and I know of no examples in Dickinson but am game to be proved wrong.)

apocopated rhyme – The reverse of trailing rhyme. finger/ring doubter/scout.

- (Again, I know of no examples in Dickinson’s poetry.)

mosaique or composite rhyme – Rhymes constructed from more than one word. (Astronomical/solemn or comical.)

- (This also is a technique which Dickinson didn’t use.)

![]()

RHYMES DEFINED BY RELATION TO STRESS PATTERN

one syllable rhyme, masculine rhyme – The most common rhyme, which occurs on the final stressed syllable and is essentially the same as true or perfect rhyme.

- 313 shamed/blamed

259 out/doubt

light rhyme – Rhyming a stressed syllable with a secondary stress – one of Dickinson’s most favored rhyming techniques and found in the vast majority of her poems. This could be considered a subset of true or perfect rhyme.

- 904 chance/advance

416 espy/try

448 He/Poverty

extra-syllable rhyme, triple rhyme, multiple rhyme, extended rhyme, feminine rhyme – Rhyming on multiple syllables. (These are surprisingly difficult to find in Dickinson. Nearly all of her rhymes are monosyllabic or light rhymes.)

- 1440 Mortality/Fidelity

809 Immortality/Vitality

962 Tremendousness/Boundlessness

313 crucify/justify

wrenched rhyme – Rhyming a stressed syllable with an unstressed syllable (for all of Dickinson’s nonchalance concerning rhyme – wrenched rhyme is fairly hard to find.)

- 1021 predistined/Land

522 power/despair

![]()

RHYMES DEFINED BY POSITION IN THE LINE

end rhyme, terminal rhyme – All rhymes occur at line ends–the standard procedure.

- 904 chance/advance

1056 June/moon

initial rhyme, head rhyme – Alliteration or other rhymes at the beginning of a line.

- 311 To Stump, and Stack – and Stem –

- 283

Too small – to fear –

Too distant – to endear –

- 876

Entombed by whom, for what offense

internal rhyme – Rhyme within a line or passage, randomly or in some kind of pattern:

- 812

It waits upon the Lawn,

It shows the furthest Tree

Upon the furthest Slope you know

It almost speaks to you.

leonine rhyme, medial rhyme – Rhyme at the caesura and line end within a single line.

- (Dickinson’s shorter line lengths, almost exclusively tetrameter and trimeter lines, don’t lend themselves to leonine rhymes. I couldn’t find one. If anyone does, leave a comment and I will add it.)

caesural rhyme, interlaced rhyme – Rhymes that occur at the caesura and line end within a pair of lines–like an abab quatrain printed as two lines (this example is not from Dickinson but one provided by Rios at his webpage)

- Sweet is the treading of wine, and sweet the feet of the dove;

But a goodlier gift is thine than foam of the grapes or love.

Yea, is not even Apollo, with hair and harp-string of gold,

A bitter God to follow, a beautiful God to behold?

(Here too, Dickinson’s shorter lines lengths don’t lend themselves to this sort of rhyming. The only place I found hints of it were in her first poem.)

![]()

By Position in the Stanza or Verse Paragraph

crossed rhyme, alternating rhyme, interlocking rhyme – Rhyming in an ABAB pattern.

- (Any of Dickinson’s poems written in Common Meter would be Cross Rhyme.)

intermittent rhyme – Rhyming every other line, as in the standard ballad quatrain: xaxa.

- (Intermittent Rhyme is the pattern of Ballad Meter and reflects the majority of Dickinson’s poems.)

envelope rhyme, inserted rhyme – Rhyming ABBA.

- (The stanza from poem 313, see above, would be an example of envelope rhyme in Common Particular Meter.)

irregular rhyme – Rhyming that follows no fixed pattern (as in the pseudopindaric or irregular ode).

- (Many of Dickinson’s Poems seem without a definite rhyme scheme but the admitted obscurity of her rhymes – such as ring/run in the poem Because I could not stop for death – serve to obfuscate the sense and sound of a regular rhyme scheme. In fact, and for the most part, nearly all of Dickinson’s poems are of the ABXB pattern – the pattern of Ballad Meter . This assertion, of course, allows for a wide & liberal definition of “rhyme”. That said, poems like 1186, 1187 & 1255 appear to follow no fixed pattern although, in such short poems, establishing whether a pattern is regular or irregular is a dicey proposition.)

sporadic rhyme, occasional rhyme – Rhyming that occurs unpredictably in a poem with mostly unrhymed lines. Poem 312 appears to be such a poem.

thorn line – An un-rhymed line in a generally rhymed passage.

- (Again, if one allows for a liberal definition of rhyme, then thorn lines are not in Dickinson’s toolbox. But if one isn’t liberal, then they are everywhere.)

![]()

RHYME ACROSS WORD BOUNDARIES

broken rhyme – Rhyme using more than one word:

- 516 thro’ it/do it

(Rios also includes the following example at his website)

- Or rhyme in which one word is broken over the line end:

I caught this morning morning’s minion, king-

Dom of daylight’s dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon, in his riding

Of the rolling level underneath him steady air, and striding

High there, how he rung upon the rein of a wimpling wing…

(I can find no comparable example in Dickinson’s poetry.)

![]()

Getting back to identifying meter (in Dickinson’s Because I could not stop for death) the final method is to scan the poem. The pattern is thoroughly iambic. The only individual feet that might be considered anapestic variants are in the last stanza. I personally chose to elide cen-tu-ries so that it reads cent‘ries – a common practice in Dickinson’s day and easily typical of modern day pronunciation. In the last line, I read toward as a monosyllabic word. This would make the poem thoroughly iambic. If a reader really wanted to, though, he or she could read these feet as anapestic. In any case, the loose iambs, as Frost called them, argue for Ballad Meter rather than Common Meter – if not its overall conversational tone.

The poem demonstrates Dickinson’s refusal to be bound by form. She alters the rhyme, rhyme scheme and meter (as in the fourth stanza) to suit the demands of subject matter. This willingness, no doubt, disturbed her more conventional contemporaries. She knew what she wanted, though, and that wasn’t going to be altered by any formal demands. And if her long time “mentor”, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, had been a careful reader of her poems, he would have known that she wouldn’t be taking advice.

If I think of anything to add, I’ll add it.

If this post has been helpful, let me know.

Thatis great!Thank U !

LikeLike

You’re welcome, Lily. Thanks so much for commenting!

LikeLike

Do you know, “If I can stop one heart from breaking” ? It was the first poem I ever read. I think I was four. It made me want to be a poet. Would it surprise you that she’s an influence along with Frost and Thoreau?

I’m not a formalist, but I do use rhyme at times, and even tried a Villanelle, here:

http://hgstewart.wordpress.com/2008/09/29/autumn-will/

Your essay was fantastic.

H

LikeLike

That was an extremely well done essay. Great Job!

LikeLike

Thanks Jeremy! I come back from time to time and try to improve them.

LikeLike

thanks

LikeLike

Didn’t realize anyone missed the meter in Dickinson until I read this. It did puzzle me that the books & essays I found didn’t talk about it. What a treat! So much fun! Can you direct me to anything you’ve written about how the music/rhythms of our time are reflected in poetry you enjoy, or don’t? Thanks so much for your work.

LikeLike

You know, I think we would have to look long and hard before we found anything comparable in the poetry “of our times”. Nearly all of it is free verse which, by definition, avoids any sort of regular patterning or rhythms. There are free verse poets who go apoplectic when I write that, but look in any dictionary and it’s part of the definition. If they’re writing poetry with a regular pattern or rhythm, then they’re not writing free verse.

That said, if you search among rappers and hang out at poetry jambs, you will hear lots of rhythm – the music and rhythms of our time.

In my experience, though, it never seems to translate to the page. It needs a performer. It’s poetry and then something more. So it would be hard for me, I think, to dissect in the same way I can dissect a poem by Dickinson.

Does that make sense?

LikeLike

Don’t worry, it’s only 12:30 here.

LikeLike

This is the best intro that I have read. You just shut up and gave me the answers. Thanks.

LikeLike

Glad that I could shut up and be helpful. :)

LikeLike

From the Last Poets through early hip-hop, rhythm & rhyme drew me in. Jazz & pop propped up the slammers & poetry jammers. I never scanned those predictable yet compelling slam melodies. Now I wonder whether they constituted changes rung on forms I should have known. It’s been a while. In 2010, “beats” have infiltrated pop music and every church seems to have a different musical style, many rather simple & pop. So I was curious if someone who studies & is aware of how musical rhythms influenced a poet in the 19th century had identified newer musical conventions that might have affected late 20th century or early 21st century poets.

I also was hoping to hear about poets who you felt more or less successfully used newer rhythms & forms.

The past ten years I’ve gone back to Auden & Dickinson, but never thought to study them as you have. I’ve also enjoyed reading Heather McHugh and Alice Fulton for their wordplay, imagery and very particular perspectives, without analyzing the underpinnings of their poems. Have you written about any living or recently living poets?

LikeLike

And it’s a very interesting subject. I would say that the one musical convention that has had the most influence on back-street poetry is rap – but so much of this , if not all of it, is performance poetry. It doesn’t sit well on the page. And the poetry that interests me is the poetry that does all its work on the page (not because I think it’s better or purer but because that’s what interests me). Dickinson wasn’t so much influenced by the music, but by the meter and rhyme scheme required by the different hymns. There is no single rhythm or rhyme scheme in rap – rap, I think, is accentual rather than accentual syllabic. There may be some examples of accentual syllabic rap, but I can’t think of any. So, it would be very difficult to write the same sort of post for performance poetry. I’m not sure it could be done. So much depends on the performer…

But that’s the thing… contemporary poets (not lyricists or performance poets) are almost universally free verse poets and deliberately avoid newer rhythms and forms. However, that said, there are thousands of poets and I think it’s virtually impossible to be acquainted with them all. There may be some modern poets comparable to Dickinson, but I don’t know about them. Elizabath Alexander, who read at Obama’s inauguration, purportedly wrote a poem based on the African Praise Song (from what region the form originates, I don’t know), but the poem could hardly be called rhythmic or song-like. It was a dud and was based on an ancient rather than modern form. That’s the only example I can think of – that’s recent.

No. Though I’ve been meaning to write up a poem by Ferlinghetti. I’m sorry to say, I just don’t find living or recently living poets (those I’m familiar with) to be all that interesting. On my Philosophy page, I write that:

And that:

Which I think is true. However, I’m not dogmatic about it. If anyone introduces me to a modern poet who fuses rhythm (pattern & form) in new and novel ways, I’ll be as enthusiastic as anyone. Take a look at Annie Finch’s poetry. I wrote a review of her poetry and much of it is very chant-like. It’s not based on “newer rhythms & forms” but it’s new in the sense that she explores rhythms that other poets have overlooked. Take a look and tell me what you think.

LikeLike

I wanted to thank you for the wealth of information and insight on your website. I am a 56 year old minstral of sorts. I had become smitten by Emily Dickinson and have been trying to understand why. I was seeking to learn about Common Hymn Meter and found this gold mine. I have written a few songs and poems, but without any method to the madness. You have given me tools I knew nothing about. Thanks for sharing your gift. I will continue to study your post and read your poems. Thanks!

LikeLike

Music to my ears… you’re welcome. :-)

LikeLike

Well done, indeed!

LikeLike

This is so well done. I’m an English teacher at an IB school, and I’m just learning WordPress myself. I see the potential now! Your explanations are crystal clear; my students will find this page invaluable.

LikeLike

Thanks for the comment Anon. It’s taken me a while to more fully appreciate WP’s potential. Glad you like the article on Dickinson. It was as much for my own education as anyone else’s. :-)

LikeLike

Wow, what a great site! Thanks for all the information! It’s really helpful

LikeLike

Pingback: The Sheaves by Edwin Arlington Robinson « PoemShape

Thanks for the information, it’s all really clear and was very helpful in allowing me to establish my own ideas about Dickinson’s poetry and to evaluate her use of meter – a really thorough and thoughtful essay, thankyou =)

LikeLike

Thanks Anon, glad you found it helpful. :-)

LikeLike

Pingback: On the subject of Rhyming « PoemShape

A well done analysis of rhyme and meter. Thank you.

I just recently re-discovered poetry after, say, 40 years since college and English 101. Actually, I recalled Frost’s “the secret sits in the middle and knows” and thought it was Dickinson. I bought the Complete Dickinson and read all the poems, (mostly) and did not find that poem, but had a good time of reading Emily.

I read a note about E. Dickinson (probably Wikipedia) which I liked and agree. “Emily did poetry like most women of the time did embroidery.” That is, without thought of fame, or any other motives other than just something to keep busy. I feel that reading Emily is like reading her diary – with innermost thoughts, revealing her soul. It is, you know. Most of her writing probably were never shown to anyone, until after her death. Or so I am informed.

Your last comment – my comment – “…Dickinson’s refusal to be bound by form. She alters the rhyme, rhyme scheme and meter…”. Well, if so, why the scholarly analysis of rhyme and meter here – Emily is not bound by it so why bother? Perhaps you can find others who color inside the lines and analyse them, perhaps?

LikeLike

Thanks Beruch, I’m not an expert on Dickinson, but I would strongly disagree with the Wikipedia quote. I could be wrong, but (on the face of it) the quote sounds very patronizing and dismissive. It might have been true for some (and men too) but many women were quite ambitious, and Dickinson esp. so. The problem (and I confess it’s one that I share) is that Dickinson really didn’t have patience for the aesthetic myopia of her era. The one editor whom she contacted immediately wanted her to edit her poetry according to the Victorian standards of the day. Dickinson would have none of it. Rather than compromise her artistic integrity, she chose obscurity. I think that it pained her, but writing in accordance with her own standards was the greater peace.

//Well, if so, why the scholarly analysis of rhyme and meter here – Emily is not bound by it so why bother?//

Because if she had been bound by the standards of the day, few (if any) of her poems would have been possible. It’s one thing to write free verse, which has less to do with poetry than prosetry, but entirely another to take a fairly rigid form and work freely within it. That makes things interesting. If Dickinson had written free verse, her poems would be much less memorable. It’s in the balance between structure and the breaking of structure that Dickinson’s genius emerges — in my opinion. :-)

LikeLike

I think that an equivalent situation would be if a woman of the 1850’s would paint like Picasso or Chagal. Of course, in those days, everyone would think the paintings were scribble and childish. Only years later would the genius be recognized. Perhaps there are paintings in a box in a barn somewhere in the midwest by some farm-wife in the 19th century, that would be now recognized as genius.

Would our imaginary painter have realized her own genius? Or would she have painted just for enjoyment and not ambitious? I opine the latter is the case with Emily. Is there any evidence to describe her with the word “ambitious”? If she really wanted to be published, and famous, she could have slanted her poetry to the times.

To repeat (or just cut and paste) I feel that reading Emily is like reading her diary – with innermost thoughts, revealing her soul. So, the best proof is the poetry itself. If she was ambitious, she would say so. Could you write that much, and be that good, and not have the real you come thru, to open your soul to the world? Therefore, from reading her, I think that she was writing for her own pleasure, and not for fame.

On a different slant, I think that I have noticed, that except for the very early poems, Emily always capitalizes her metaphors.

LikeLike

Since so little is known of Dickinson’s inner life, you may be absolutely right in your conjecture. I guess my own opinion is based on intuition and just a little bit of evidence. We know that Dickinson sent over a 100 poems to Thomas Wentworth Higginson. Here’s how the brief bio at the Emily Dickinson Museum puts it:

Higginson had a long association with the Atlantic Monthly, contributing a number of articles, essays and poems. In the April 1862 issue, he published “Letter to a Young Contributor,” in which he encouraged and advised aspiring writers. Within a month, he received a note from Emily Dickinson, then 31 years old, along with four poems, thus beginning a relationship that was to last until the poet’s death in 1886.

Within a month… this doesn’t sound like a poet stitching glorified placemats. Dickinson was also friends with Samuel Bowles, editor-in-chief of the Springfield Republican. Bowles, single handedly, could have elevated Dickinson’s reputation. They were genuinely friends, I think; but I also intuit a little design behind her friendship. Unfortunately, Bowles’ taste in poetry seems to have been fairly conventional and uninspired. I think, for that reason, Dickinson never took advantage of the friendship as she might have. But that she was friends with two such potentially formidable allies tells me she was not without ambition.

I sympathized with her. I think she deeply resented rejection. That’s a hard trait to mix with ambition, I know.

LikeLike

Excellent page. I have recently learnt ‘Exultation is the going’ by heart and sing it to the Sacred Harp tune Beach Spring. I would like to know if anyone else has found a good matching tune for poems by Emily. I can’t find a tune for ‘I reason: Earth is short’ (metre 6644).

On her life, Lyndall Gordon’s brilliant book ‘Lives like Loaded Guns’ suggests she had epilepsy. I find this convincing.

LikeLike

Hi Emma, I haven’t read the book, but I’ve heard this supposition elsewhere and I agree that it might explain a few things.

Don’t think I can help you with a tune. A knowledge of folk music is just the thing for that, and that’s not the kind of music I really listen to. Probably a hymn tune — all of Dickinson’s poems, after all, are grounded on their meter. I wonder if she heard much other music? Maybe you need one of those hymn books?

LikeLike

I feel as though I am years late to class here but what a wealth of information. A new perspective for me on E.D. who I tend to read aloud with no analysis of her use of any kind of meter. It makes sense of course that she would write in a hymn-like way. No matter what she’s writing about its that familiar rhythm that elevates her words to a sacred level. “The Grass so little has to do- A Sphere of simple Green- With only Butterflies to brood And Bees to entertain-”

A worthy, smart site.

LikeLike

Thanks Peter. The posts may be old, but I always try to respond. Glad you liked the post on E.D.. :-) She must have sung lots of hymns in her lifetime, though I wonder as to how “religious” she really was.

LikeLike

Thank you for the excellent discussion of meter in Dickinson. I’ve taught Dickinson in my university literature courses for many years, and admired her genius for decades before that. I’ll just offer a few of my own observations:

1) While I much appreciate your detailed breakdown of hymn meter, common measure, and ballad meter, any discussion of Dickinson’s use of form must acknowledge how she uses dashes to disrupt those forms. If one reads her work aloud without pausing at the dashes, it does become somewhat sing-song, which in no way suits her topics or the depth of her insights. The dashes are most significant when they represent what I call atemporal breaks, which are moments in her poems when a potentially vast amount of time could have passed without change.

For example, the suffering — specifically the thought that she was going mad — she describes in #340 (“I felt a Funeral, in my Brain”) is not something she dealt with in an afternoon or day. When she writes, “Kept treading — treading” and “Kept beating — beating” she is describing an ongoing agony. When she writes, “Wrecked, solitary, here — / And then a plank in Reason, broke” that collapse of her rational mind comes as an inestimable mercy after some long period of torment. If a reader just plows through those dashes as if they don’t exist, we lose all of that.

Similarly, #588 describes an entire lifetime in eight lines:

The Heart asks Pleasure — first —

And then — excuse from Pain —

And then — those little anodynes

That deaden suffering —

And then — to go to sleep

And then — if it should be

The will of it’s Inquisitor

The privilege to die —

Every time we hit a dash, years might pass. But of course in retrospect, it’s an eye-blink, and she insists that we all end up in the same place eventually. And note that the poem ends not with death, but with begging for death, followed by another dash: one might end up begging a long time.

One way Dickinson was truly revolutionary is that she found a way to make silence part of her poems. Usually silence surrounds a poem, but with Dickinson, it’s part of the text — and sometimes the poem continues even after it can no longer be spoken. That’s why Hart Crane, in his poem to her, called her “sweet, dead Silencer.”

2) Dickinson had great faith in her own poetic genius, especially during the time when she was writing hundreds of poems per year. (She slowed down dramatically after 1865.) We can see the evidence in her poems. Of course, most people know #519 (Franklin numbering), which begins “This is my letter to the World / That never wrote to me” but ends with her addressing future “countrymen,” which at least implies she believes her works will be read. But even better evidence is #448:

I died for Beauty — but was scarce

Adjusted in the Tomb

When One who died for Truth, was lain

In an adjoining Room —

He questioned softly “Why I failed”?

“For Beauty”, I replied —

And I — for Truth — Themselves are One —

We Bretheren, are”, He said —

And so, as Kinsmen, met a Night —

We talked between the Rooms —

Until the Moss had reached our lips —

And covered up — Our names —

Keats, of course, was the poet who said (or more accurately had the Grecian urn say) that Truth and Beauty are the same thing. Keats was also Dickinson’s favorite poet — she had remarkably good taste. Like Dickinson, Keats had labored in obscurity (not as obscure as Dickinson) during his life, but at the time she wrote this, more than forty years after his death, Keats was well on his way to being regarded as one of the greatest poets in the history of the English language.

So here is Dickinson imagining that upon her death she will metaphorically be interred next to Keats, that Keats and she are “Kinsmen,” and that they will continue to talk with each other — which we can read as their works being in conversation with each other’s — until both of their names are covered up, meaning until both are forgotten. If believing that her name will last as long as Keats’s doesn’t express confidence in her own poetry’s power, nothing does.

3) Regarding her religion: one can’t understand Dickinson’s religious thought without reading Emerson. Emerson, who himself was influenced by the English Romantics, sought spirit in nature, and his concept of an Oversoul is effectively a non-anthropomorphic, non-gendered, universal spirit. #236 “Some keep the Sabbath going to Church –” is a fine expression of this idea. In contrast, when she writes about YHVH, she is highly critical; she regards him as something of a bully. Her comments on Christ are more sympathetic, but they involve a strange level of identification: he seems mostly a means for her to explain her own level of suffering.

Note that Dickinson’s relationship with his sister-in-law Susan apparently broke down over Susan’s insistence that the Dickinsons, who had never been a conventionally religious family (they knew Emerson personally, and Emerson stayed at Austin Dickinson’s house when he lectured in Amherst), join the local church. Susan’s motivation appears to have been more social than religious — she was determined that she and her husband would be the leading citizens in Amherst. The rest of the Dickinsons went along, but Emily refused.

4) Reading Dickinson and Walt Whitman side-by-side is fascinating. Both admired Emerson and were deeply influenced by his ideas. They were probably the two greatest poets the U.S. has ever produced. They were contemporaries, and lived a few hundred miles from each other, yet we have no evidence that either ever read the other’s work. Dickinson mentions in a letter that she was told Whitman was “obscene” (and though I’m not convinced that would have stopped her, they are so different I don’t think she would have liked him, at least initially), and almost none of Dickinson’s works were published until the last year or two of Whitman’s life, when he wasn’t doing much reading.

What is fascinating is that they both start with Emerson and then take him in completely different directions, both philosophically and stylistically. Whitman is expansive; Dickinson is a miniaturist. Whitman expresses total confidence in his role as a poet, to the point where he intended “Leaves of Grass” to be a new American bible; Dickinson consciously avoided the limelight and was content with posthumous fame. They’re both magnificent, but they are like matter and anti-matter.

LikeLike

Hi Richard, thanks for that great addition to the post! Some questions:

1.) I’m inclined to agree with you on her use of dashes. I’m curious though, is this simply your opinion, opinion you’ve inherited from others, or do we have some record of what Dickinson thought?

2.) Inasmuch as any number of poets (and contemporaries of Dickinson) had “great faith in their poetic genius” (including me, by the way), and inasmuch as only a handful of them were right (and that may not include me), Dickinson’s self-confidence is only interesting insofar as she didn’t pursue recognition (in the shameless way that Whitman did, for example). My guess is that she didn’t handle rejection well, especially rejection graced with the self-anointed, benevolent presumption of the advice-giver. If so, then I get it. I really, really get it.

3.) Interesting perspective on Dickinson’s religious outlook. I haven’t given it as much consideration, but based on her poetry I’d say she was of an independent mind (which is to say, she was more of a theist than a deist) and, as you say, there’s her identification with Christ.

4.) How “content” was Dickinson, really, with “posthumous fame”? I wonder about that. I see some bitterness in the matter, and also that her output eventually suffered for the lack of recognition. What do we know from Dickinson? I have a biography of hers I’ve been meaning to read, it’s high time.

LikeLike

Very thorough! My piano background and playing hymns in church when I was 13 really helped me to understand.

LikeLike

Hey, that’s cool. Wish my own piano playing were respectable enough for that sort of thing,

LikeLike

I’m knew to this blogging and happy I stumbled across this. I love rhyming poetry and hate free verse. I hope to make rhyming popular again. I simply write poems that touches people hearts. I’m self taught and gotten better with age. I use the same rhyme schemes as Dickinson before I even knew who she was. Lol I look forward to reading more of your stuff.

LikeLike

The little secret is that rhyming poetry is still by far and away the most popular form of poetry—just look at rap, Mother Goose, or consider that the best selling books of poetry remain, primarily, books of metrical and rhyming poetry. :) Build your blog, and they will come. And isn’t that something that you picked up on Hymn Meter without even realizing it.

LikeLike

Thanks!

LikeLike

Maybe it’s because I’ve grown up in the church, but I’ve always had that affinity towards the meters of hymns. I never realized the relation between the niche that is hymn-writing, and Emily Dickinson, though I knew “I like to see it lap the miles” was C.M.

LikeLike

That’s a really useful post, but if you’ll forgive me for making one correction, the first poem Dickinson wrote consists of hexameter lines, not fourteeners: six beats to the line, not seven.

I would also suggest advising beginners to count beats rather than syllables: it’s easier, it highlights the rhythm, and it avoids any potential confusion caused by anapests or feminine endings.

LikeLike

Hi Kier, thanks for the comment.

Identifying that poem as a fourteener doesn’t originate with me. The reason it’s called a fourteener is because of its syllabic count, not its “beats” (or accented syllables). And that’s the problem with asking beginners to count “beats” rather than syllables when identifying common meter, because common meters go by the number of syllables, not “beats”. In other words, the foremost consideration in common meter is not the meter (which could be anapestic rather than iambic especially in Dickinson’s hands) but the syllable count—which is the reason Dickinson’s first poem is considered a fourteener despite only having six “beats”.

LikeLike

Um…no!

Indeed, as you said yourself, Patrick, ballad meter (as opposed to common meter) has a varying syllable count, as anapests can be freely employed.

And the lines of Dickinson’s first poem also have a varying syllable count (the opening one, for instance, has 15); but they all have the same number of beats!

Ballad meter absolutely goes by the number of beats, and fourteeners absolutely have seven beats – and don’t include anapests, which is why they can be reliably described as containing 14 syllables.

LikeLike

If common meter goes by the number of beats (whatever that means), then why aren’t they named after their beats? They’re not. They’re named after their syllable count, and the reason is because you have common meters like 7,6,7,6.

If sin|ners will |serve Satan,

And join |with one |accord,

Dear breth|ren, as for |my part,

I’m bound |to serve |the Lord;

And if |you will go |with me,

Pray, give |to me |your hand,

And we’ll |march on |together,

Unto |the prom|ised land.

The “beat” count is 3,3,3,3 and there’s nothing regular or strictly iambic about this lyric. It’s a mess. Worse, 7,7,7,7 also has a “beat” count of 3,3,3,3. When you’re talking about 8,6,8,6, it’s all well and fine to insist that the “beats” trump the syllable count. 8,6,8,6 is nearly always iambic, but hymns are much more than they’re “beats”, and that brings me to the word “beat”. I’ve never liked your use of it because it’s contradictory In some corners a “beat” is synonymous with the metrical foot while for others, like linguists, it’s synonymous with a stressed or accented syllable (which is how I understand the term). So, if “beats” means feet, then it’s relatively useless for differentiating common meters, and if “beats” means stressed syllables, then it’s also misleading because any given foot may not have a “beat”. Insisting on identifying common or ballad meters according to “beats” is going to be utterly confusing to anyone identifying them, which is why nobody in the business does it that way. Then you insist that fourteeners “absolutely have seven beats”, how about this then?

If you’re lucky on Monday and your happy on Tuesday

Just keep at it on Wendesday you’ll be skipping on Thursday…

Those are fourteeners that do not have seven “beats” no matter how you interpret “beats”.

I expected you to quibble by asserting that Dickinson was a poet and not a hymnist, and that therefore we should read her poems as poetry and not hymns. There’s an argument to be made there, but not much of one. Dickinson never wrote a poem that wasn’t in some way inspired by hymn meter, so one can be pretty secure in asserting that she probably thought in terms of syllable count rather than meter when writing her poems. That said, I scanned her poem like a poet, and that might be misleading, especially for a reader who considers my division of her poem into feet/”beats” as the paramount consideration. But if one goes with the assumption that Dickinson was thinking in terms of hymn meter and syllables (many of her stanzas are loosely based on 8,6,8,6) then her first poem starts out no differently:

Oh the Earth was made for lovers, for damsel, and hopeless swain,

That’s four accented syllables before the “hemistich” followed by three accented syllables afterward. That’s essentially an 8,6,8,6 hymn. Put those together and you have 14,14 —> fourteeners.

For sighing, and gentle whispering, and unity made of twain.

All things do go a courting, in earth, or sea, or air,

That said, typically of Dickinson, she doesn’t hold the pattern. Some lines have more accented syllables and some less. Some have more metrical feet and some less. Some lines are 14 syllables, many are 13, and some are 15.

Earth is a merry damsel, and heaven a knight so true, (14)

And Earth is quite coquettish, and beseemeth in vain to sue. (15)

Now to the application, to the reading of the roll, (14)

To bringing thee to justice, and marshalling thy soul: (13)

So, if she’s writing fourteeners, then they’re loose fourteeners (just as so many of her other poems are loosely based on hymn meters). You can say that she was writing “hexameters” and therefore they’re not fourteeners, treating her poem as poem rather than hymn,, but given that all of Dickinson’s poems are based on hymn meter, I’d argue it’s more accurate to say she was writing loose fourteeners. Edit: See my later comment where, if the poem is sung to Gilligan’s Island, it can be scanned as Tetrameter/Trimeter.

Edit: And as an example of her loose “hexameters”:

The life |doth prove |the precept,|| who obey |shall hap|py be, (6 Metrical Feet) 14 Syllables

Who will not | serve the sovereign, || be hanged | on fat|al tree. (5 Metrical Feet)

Given the pattern, one could also read this as:

Who will | not serve | the sovereign, ||

The high |do seek |the lowly, || the great | do seek | the small, (6 Metrical Feet)

None | cannot find | who seeketh,|| on this || terres|trial ball; (6 Metrical Feet) 14 Syllables

The bee | doth court | the flower, || the flow| er his suit | receives, (6 Metrical Feet) 14 Syllables

Six true, | and come| ly maidens ||sitting |upon |the tree; (6 Metrical Feet)

And they make | merry wedding,|| whose guests |are hund|red leaves; (5 Metrical Feet)

This line can also be read as six feet, but requires a bit more shoehorning to pull it off:

And they | make mer|ry wedding, || (Keeps the iambic pattern but sounds awkward.)

Or

And they make | merry | wedding || (Which is probable.)

I’m not sure what sounds the most natural, but this is typical of Dickinson’s “rough” formulation, in my opinion, of meter and accentual syllabics (which isn’t to imply it’s a bad thing).

The wind |doth woo |the branches,|| the branch|es they| are won, (6 Metrical Feet)

And the fath|er fond | demandeth ||the maid|en for |his son. (6 Metrical Feet) 14 Syllables

The storm |doth walk |the seashore || humming |a mourn|ful tune, (6 Metrical Feet)

Edit: I corrected my prior comment to read that syllable count is the most important when identifying “common meters” rather than “ballad meters”. I keep reversing the two….

LikeLike

Also, just want to clarify:

Hymn Meter: Identified by number of syllables (hence their categorization). Not “beats”. Then broken down into Common, Long, Particular Meters, etc…

Ballad Meter: Ballad meter isn’t categorized. Ballad meter is essentially one or another common meter with variant feet and examples are best identified by the number of accented/stressed syllables in each line (at which point one can say that it’s 8,6,8,6 with variant feet, for example, because syllable count is how hymn meters are categorized). To borrow the definition from the English Ballad Broadside Archive: ““Ballad measure,” sometimes called “ballad stanza” or “ballad meter,” can be strictly defined as four-line stanzas usually rhyming abcb with the first and third lines carrying four accented syllables and the second and fourth carrying three. Looser definitions describe ballad measure as consisting of quatrains with four or three stresses in each line and with an abcb or abab rhyme scheme.“.

Dickinson’s Poetry: Dickinson, for the most part, wrote neither common nor ballad meter, but wrote poetry inspired by and based on the syllabic and accentual patterning of hymn meter. Her lines are roughly syllabic and are roughly accentual.

LikeLike

Just in relation to your 7,6,7,6 hymn first of all, yes, it is strictly iambic! The seven syllable lines have a feminine ending.

I’ll read and respond to the rest if I get round to it!

LikeLike

If you’re lucky on Monday and your happy on Tuesday

Just keep at it on Wendesday you’ll be skipping on Thursday…

Goodness me, Patrick, these are not fourteeners! A fourteener is not any line that contains 14 syllables; purely syllabic meter is a modern invention and did not exist when the term “fourteener” was coined.

If we can’t even agree on what constitutes a beat, then I think we’re just stuck here! If you tap out the rhythm of a metered line, you will tap on the beat syllables, so I simply don’t understand your own definition of beats, and it’s plain by now we’re not going to understand each other!

I find some of your proposed scansion very dodgy – but there it is!

Thank you for taking the trouble to respond anyway!

LikeLike

And, no, beats don’t “mean” feet. Foot division is a purely artificial means of dividing up the line in such a way that it accommodates the beat placements (or at least, that’s the idea). What *defines* a meter is beat placement and the number of beats (except in modern syllabic meter).

But I know we’re not going to agree on that! I’m just clarifying in light of your own comments.

LikeLike

Beats don’t mean feet to you, but they do to others. All you have to do is search for a definition of “beats” and you will find it defined, by some, as a metrical foot. This confusion about beats is why I don’t use the term. In one sense, it makes sense to conflate a beat with a metrical foot because, as some will probably argue, each foot can only truly have one beat. But then what to make of the Pyrrhic foot, which doesn’t have a beat or the Spondee (which might give an IP line 6 beats)? In that case, saying that all Iambic Pentameter lines have 5 beats isn’t true. Some have only four and some have six fairly regularly. However, it can be said that an IP line nearly always has 5 feet/beats even with a Pyrrhic foot if beats are metrical feet. So, what defines a given meter clearly is not always the number of beats, if beats mean accented syllables, but the number of feet. But I just avoid the term.

LikeLike

“Beat” should absolutely not be a controversial term for any kind of rhythmic verse. But we’ll leave it there, Patrick: I know if I try to argue the point with you, I’ll just end up exhausted!

LikeLike

No, it should not be, but it is. You’ve got a problem. John Drury in “the poetry dictionary” defines a “beat” as “an emphasis on a particular syllable”. Period. End of discussion. My other dictionaries and Encyclopedias (including the Princeton), don’t even have entries for “beat”. And that tells you something. Meanwhile, look it up online, and you get this from The Pen & the Pad:

“Each foot has one stress, or beat. Similar to everyday speech, poetry also repeats the natural intonation, stresses, pauses and beats of conversation.”

Which all but equates a foot with a beat because if every foot has a beat then a beat must be or be like a foot. And it isn’t correct. Some metrical feet don’t have beats.

And if someone looking up “beats” stumbled on the Your Dictionary website, they would be met with this:

“Meter is a unit of rhythm in poetry, the pattern of the beats. It is also called a foot. Each foot has a certain number of syllables in it, usually two or three syllables. The difference in types of meter is which syllables are accented or stressed and which are not.”

Which could easily be construed as calling a beat a foot, and maybe that’s what the author means. It’s not clear. To you, the meaning is clear. To anyone reading these articles? Not so much. At Poem Analysis.com, the equating of a “beat with “a foot” is made explicit:

“This is a very common metrical foot known as an iamb. Tetrameter consists of four feet. In this case, they are iambs. The even-numbered lines contain one less beat, or foot, making them iambic trimeter. ”

So, despite your protestations, when you talk to me about “beats”, I’m never sure whether you’re talking about stresses or feet. Sometimes it’s not even clear from the context of your writing. It’s unfortunately an imprecise term. It may be precise to you, but clearly it’s usage elsewhere is imprecise.

LikeLike

As I’ve said, foot division is artificial, and the idea is that each “foot” contains one beat; the foot divisions mark off the beats in other words. That really isn’t complicated! (Though individual foot division does not work in iambic meter where a beat is pumped forward: the “di-di-DUM-DUM” pattern that is then formed can only usefully be described as a double foot. But that’s another issue again, and I know we won’t agree on that!).

I agree the sources you quote are very inadequate in their explanation. The last one is at least not inaccurate: as every foot contains a beat, one less beat does indeed mean one less foot.

And as I’ve stated, if you tap out the rhythm as you read a passage of metered verse, the syllables you tap on are the beat syllables. If you can hear the rhythm, it’s self-evident which are the beat syllables.

It’s baffling me why you’re unable to recognise that, but there it is! But rhythm implies beats, yes? The two go hand in hand. You literally can’t have one without the other!

LikeLike

//….one less beat does indeed mean one less foot.//

And there we go. Anyone unfamiliar with meter is going to be confused by your assertion and think that a beat and a foot are the same. One would think in your system of metrics that pyrrhic feet don’t exist. And maybe they don’t?

//And as I’ve stated, if you tap out the rhythm as you read a passage of metered verse, the syllables you tap on are the beat syllables. It’s baffling me why you’re unable to recognise that…//

Recognize what? You mean I can’t recognize a “beat” or “rhythm” or that I can’t recognize your argument? What you’re writing right now is beyond confusing, and that you don’t know why is what’s baffling. Tell that to anyone unfamiliar with meter and, yes, they can go through a speech by Shakespeare and tap out the Iambic rhythm on every second syllable (because what do you mean by a “beat syllable” after all and what do you mean by “rhythm”?) but that doesn’t mean the word “the” in the first and second line is the “beat”:

A mote it is to trouble the mind’s eye.

In the most high and palmy state of Rome,

But then maybe they’re “beat syllables”? Which is maybe not the same as the syllable receiving the “beat”? Who knows? The rhythm (more obfuscation) is regular because otherwise it’s not a rhythm. It’s something else: https://poemshape.wordpress.com/2012/03/10/free-verse-an-essay-on-prosody-%e2%9d%a7-a-review/ And so your final conclusion is also confusing:

//But rhythm implies beats, yes? The two go hand in hand. You literally can’t have one without the other!//

If you’re still interpreting beats as “accented syllables”, then no, the two don’t go hand in hand in poetry. The accented syllable doesn’t always land where a stress (or beat?) is expected. But then who knows what you mean by “beats” and by “rhythm” and “beat syllables”? Your nomenclature is a complete mess.

LikeLike

A mote it is to trouble the mind’s eye.

In the most high and palmy state of Rome,

You’re right the word “the” is not a beat syllable in those lines – for a reason I have *already* explained: in both cases the beat has been pumped forward (just as a beat can also be pulled back, which is where traditionally we mark off a “trochee”).

-ble the MIND’S EYE

in the MOST HIGH

A displaced beat occurs where two adjacent syllables *swap* stress level. So either…

DUM-di-di-DUM (instead of “di-DUM-di DUM”)

…or…

di-di-DUM-DUM (as opposed to “di-DUM-di-DUM”).

In the first example the 1st and 2nd syllables have swapped stress level, creating a displaced beat.

In the second example the 2nd and 3rd syllables have swapped stress level, creating a displaced beat.

I *know* you are going to throw your hands up about that!

As to your point about pyrrhics, I responded to that previously too: “And, yes, scanned correctly, all feet *do* contain a beat: a pyrrhic contains a destressed beat and a spondee contains a stressed offbeat”.

The *beat* is, by definition, the core feature of metered verse, which *ought* to be a completely non-controversial thing to say.

And beats can be displaced, as I’ve shown. They can be destressed (the pyrrhic). And offbeats can be stressed (the spondee).

Foot division is no more than an attempt to divide a metered line up into smaller parts in such a way that it marks off the beats (an unsuccessful attempt where the pattern containing a beat that’s pumped forward, “di-di-DUM-DUM”, is divided in half. The fact that you recognised that the 2nd sylllable in that pattern is not a beat only helps prove my point!).

LikeLike

Yes, I understand all this.

The point I’m making, and that your current comment in no way remedies, is that the term “beat”, as you use it, is utterly confusing because its meaning is contingent on context. The very fact that you have to write a comment like this should be a tip-off that something’s gone wrong. Here’s Drury’s complete definition of a “beat”:

BEAT (also called *accent or *stress) Emphasis on a particular syllable. A three-beat line (such as Theodore Roethke’s “The hand that held my wrist” from “My Papa’s Waltz”) contains three accents or stresses (hand, held, and wrist).

He makes no mention of a “BEAT” being a hypothetical rhythm, no mention of destressing or of “displacement” (which implies that there’s a hypothetical/metrical beat and a not-hypothetical/accentual beat). He doesn’t say, for example, that an iambic pentameter line always has five “beats” because, according to his own definition, it sometimes will have four and sometimes will have six beats. So, the number of feet in a line is not the same as the number of beats in a line unless, that is, you treat the meaning of “beat”, as you do above, as wholly contextual.

LikeLike

Okay, here’s the whole poem:

The whiskey on your breath

Could make a small boy dizzy;

But I hung on like death:

Such waltzing was not easy.

We romped until the pans

Slid from the kitchen shelf;

My mother’s countenance

Could not unfrown itself.

The hand that held my wrist

Was battered on one knuckle;

At every step you missed

My right ear scraped a buckle.

You beat time on my head

With a palm caked hard by dirt,

Then waltzed me off to bed

Still clinging to your shirt.

All the lines have 3 beats.

“Still clinging to your shirt” has 3 beats, regardless of the fact that the opening offbeat is stressed.

“My mother’s countenance” has 3 beats, despite the fact the last beat is destressed.

Now, if you’re going to tell me, Patrick, that after reading the whole poem out loud, tapping your foot to the rhythm, what you *hear* is 4 beats in the first line I’ve picked out and 2 beats in the second, and that’s how many times you tapped your foot, we have nothing further to discuss!

LikeLike

I don’t even know what point you’re making?

Yes, Roethke’s poem is what Drury uses to demonstrate that, according to his definition, a “beat” is an accented syllable. I have no problem with that. What is confusing is when you say something like this: “…scanned correctly, all feet *do* contain a beat: a pyrrhic contains a destressed beat and a spondee contains a stressed offbeat.”

First of all, what does “scanned correctly” mean? Scanned according to

Attridge’stheory of scansion? (Edit: As was correctly pointed out, this was not Attridge but David Kepple-Jones.) That’s almost insufferably pompous. And how does calling something a “destressed beat” clarify anything? Or a stressed “offbeat”? As opposed to simply calling a foot a Pyrrhic or Spondaic foot? It’s just a new name for an old dog. The day you latched onto David Kepple-Jones’s book is either the best or worst thing that happened to you. His book is the one, from what I can tell, that got you dogmatically throwing around the word “beat”. Kepple Jones’s use of the word “beat”, within the confines of his theoretical framework, serves an explanatory purpose, but outside of that framework and in every day usage it’s needlessly convoluted and ultimately confusing.Furthermore, Keppel-Jones’s theory of meter is primarily interested in what poetry tells us about meter. (As opposed to George T. Wright, for example, who is primarily interested in what meter tells us about poetry.) To wit: Keppel Jones teaches in the Department of English at University College of the Cariboo. He’s not a poet. And there’s nothing wrong with that. He’s a metrist in a long line of metrical theorists who have created their own methods of scansion. One can take or leave his theoretical constructs but they add nothing to our understanding of any individual poem’s meaning. Nothing. We already have a theory of meter, several hundred years old, that’s been doing that. It’s very simple and it’s the one I use. All that said, the one thing Keppel-Jones’s book might be good for, as I wrote in my review, is authorship studies. His method of classifying the different stress patterns that prevailed between authors and epochs is useful and insightful.

I wanted to master meter because I wanted to write metrical poetry. I’m not interested in being a master metrist. (Isn’t that what you call yourself on Quora? Or something like that?) But being a master metrist doesn’t make one a poet or a particularly insightful reader of poetry (any more than being a musical theorist makes one a concert pianist). Reading Keppel-Jones seems to have turned you into somewhat of a dogmatist unfortunately—judging by your insistence, for example, that the only true fourteener is iambic.

Also, your initial objection appears to have been grounded in a misreading of my post. That launched us into a fussy and dry debate over meter and how hymns are classified, which you seem to have conflated with poetry (hence your triumphant but misplaced declaration that Blake’s lines couldn’t be “defined by syllable count”).

And that brings me back to your initial piece of advice:

“I would also suggest advising beginners to count beats rather than syllables: it’s easier, it highlights the rhythm, and it avoids any potential confusion caused by anapests or feminine endings.”

Which I consider disastrous advice, given both the confusion around beats (are they accented syllables? are they feet?) and the fact that 6s,7s and 7s,6s can have the same number of “beats” (and that doesn’t even bring into consideration Keppel-Jones’s “silent beats” or Attridge’s “virtual beats”). The method used by hymnists for hundreds(?) of years works fine.

I do agree, however, that we have nothing further to discuss.

LikeLike

I haven’t read Attridge.

LikeLiked by 1 person

//I haven’t read Attridge.//

You’re right. It wasn’t Attridge, but David Kepple-Jones. “Variations in the Literary Iambic Pentameter.”

My comments were reflective of Keppel-Jones, not Atrridge, and I’ve edited my comment to reflect that. Edit: Keppel Jones quotes and draws on Attridge throughout his book, which is probably what threw me off, but I should have checked my book reviews before commenting. Other than that, we’re done. And I’m editing your comment to reflect that.

P.S.S. And thank God I still have my copy of Keppel-Jones’s book. I’m just noticing that they’re asking over a hundred dollars for a used or new copy and over $800 for the “collectible”.

LikeLike

Patrick, may I respectfully ask why you edited my last comment to delete *everything* apart from my very last sentence?

LikeLike

Because I was thinking of Kepple-Jones, not Attridge, and wanted to credit your comment for the correction.

As for the rest, too many of your comments feel like you’re baiting me with rhetorical questions and straw man formulations. There’s no enjoyment in having to repeatedly clarify ideas or attitudes you ascribe to me (implicitly or explicitly) but that I haven’t expressed; and so I removed yet another rhetorical question. As for “beats” and “rhythm”, I don’t know how I can put it any more plainly: using these words in reference to poetic meter is done by professional metrists and amateurs alike but in the aggregate they’re usage is demonstrably confusing and often contradictory. Demanding that anyone tap the “rhythm/beats” of Roethke’s “My Papa’s Waltz” doesn’t in any way, shape or form address that. Lastly, there’s nothing more to add as far as identifying hymns and Dickinson’s poetry goes. Not everybody hears the same “beats” or accented syllables in a given line, especially beginners (many foreign language readers have trouble recognizing English language stress patterns) , but everybody can count syllables and given that that’s how common hymns are organized, that’s why I recommended it. Tired of discussing it. If you want to write you’re own post on hymn meter and Dickinson, go right ahead.

LikeLike

Just to add for clarification, yes, Keppel-Jones does mention Attridge, as well as others, and has points of both agreement and disagreement with him.

LikeLike

Yes, and Attridge with Kepple-Jones and these two with Robert Wallace and Robert Wallace no doubt with Dana Gioia or Rachel Hadas or David Rothman. Endless. It’s a linguist’s debate. What does calling something an “extra-syllable ending” rather than a “feminine ending” tell us about a poem? Nothing. (It also short-circuits Shakespeare’s deliberate use of feminine endings in his 20th Sonnet.) Personally I prefer “feminine ending” because it’s not flavorless and academic. But, to be fair, poetry is not what these debates are about.

LikeLike

From a technical point of view I don’t think it matters what you call it! Personally, I like to cal it a “tail”.

LikeLike

And, yes, scanned correctly, all feet *do* contain a beat: a pyrrhic contains a destressed beat and a spondee contains a stressed offbeat.

As I said, if you can *hear the rhythm* the beat syllables are self evident. If you were to tap out the rhythm while reading, the beat syllables would be those you tap on.

LikeLike

Yes, I understand what you’re saying, but you’re terminology makes an utterly confusing mess of everything.

Earlier you very forcefully defined a “beat” as a stressed syllable, but now you seem to define beats as the hypothetically stressed syllable of a given foot, and maybe that’s what you mean by a “beat syllable” which may not be a “beat”, as in a stressed/accented syllable, but a syllable in the hypothetical “beat position’ . In that case, your “beat” is not a “beat” but a “destressed beat” which is not a “beat’ in your former sense but remains a “beat” in your latter sense.

LikeLike

//A fourteener is not any line that contains 14 syllables…//

A fourteener is most commonly iambic, but need not be. Blake’s fourteen syllable lines from the Book of Thel, though not iambic, are considered fourteeners. If you disagree, you’ll have to take that up with others besides me. Fourteeners can also be composed of dactylics, as in classical meter.

LikeLike

They absolutely are iambic! Patrick, what are you talking about?

Opening stanza:

The daughters of Mne Seraphim led round their sunny flocks.

All but the youngest; she in paleness sought the secret air.

To fade away like morning beauty from her mortal day:

Down by the river of Adona her soft voice is heard:

And thus her gentle lamentation falls like morning dew.

It’s perfect iambic pentameter!

LikeLike

You didn’t mean to write “pentameter” but “heptameter”. And yes, those are perfect iambics, but as the poem progresses he introduces variant feet, extra syllables, and closes with lines like these:

“”Why cannot the Ear be closed to its own destruction?

Or the glistning Eye to the poison of a smile?

Why are Eyelids stord with arrows ready drawn,

Where a thousand fighting men in ambush lie?

Or an Eye of gifts & graces, show’ring fruits and coined gold?

Why a Tongue impress’d with honey from every wind?

Why an Ear, a whirlpool fierce to draw creations in?

Why a Nostril wide inhaling terror, trembling, and affright?

Why a tender curb upon the youthful burning boy?

Why a little curtain of flesh on the bed of our desire?”

So, no, Blake’s fourteeners are not perfectly iambic.

LikeLike

And those lines are no longer defined by syllable count, are they? They don’t all contain 14 syllables.

LikeLike

//And those lines are no longer defined by syllable count, are they?//

No, because he was writing a poem, Kier, not a hymn, and his poem was not based on the metrical features of a hymn.

LikeLike

Obviously I did *not* mean to say “iambic pentameter” in that last response! I meant to write “perfect iambic meter”.

LikeLike

Yes, that’s what I assumed.

LikeLike

True, you could make the argument that it’s strictly iambic

If sin|ners will |serve Satan,

And join |with one |accord,

Dear breth|ren, as | for my part,

This would require putting emphasis on “as” and “my”. That’s reasonable.

I’m bound |to serve |the Lord;

And if |you will | go with me,

Here too, one could put the emphasis on “will” and “with”. That would require setting off”if you will” with commas. That would read: “And, if you will, go with me.” It’s possible that in the original hymn these commas are there or were implied by the meter.

Pray, give |to me |your hand,

And we’ll |march on |together,

Unto |the prom|ised land.

Edit: That said, this isn’t a poem. It’s a hymn. I can’t find a recording of the hymn and I don’t have a hymn book. How it’s sung may or may not be “strictly” iambic. Is an ending phrase sung as a feminine ending, for example, or as an anapest? I don’t know.

This hymn, however, plainly is not iambic:

Sinner, go, | will you go,

To the high| lands of heaven;

Where the storms | never blow,

And the long | summer’s given?

Where the bright | blooming flow’rs

Are their od|ors emitting;

And the leaves |of the bow’rs

On the breez|es are flitting.

Where the saints | robed in white,

Cleansed in life’s | flowing fountain,

Shining, beaut| eous, and bright,

Shall inhab| it the mountain.

Where no sin, nor dismay,

Neither trou|ble, nor sorrow,

Will be felt | for today,

Nor be feared | for the morrow.

And here are 8s, called Green Fields:

How ted|ious and taste| less the hours,

When Jes|us no long|er I see!

Sweet pros|pects, sweet birds |and sweet flow’rs,

Have lost |all their sweet|ness to me;

etc…

Also not Iambic, though it could be. It’s the syllabic count that matters, not the meter.

LikeLike

No. Just no.

The first example consists of anapests.

The second example consists of an opening iamb in each line, followed by anapests. Which is true of all the hymns covered under 8s.

The form is a combination of the number of beats and the type of feet used, in which order (and in a previous form you exemplified, on the placement of feminine endings).

Your trying to reduce all this to nothing more than syllable count is bizarre. I’m sorry!

LikeLike

Yes, that’s my point, the first example consists of anapests 6s,7s. And this is also 6s,7s:

Go sinner, sin no more

Be joyful! Lord Jesus waits.

Go sinner, try his door,

There to save you from your straights.

Etc…

“Which is true of all the hymns covered under 8s.”

Here are 8s that are iambic:

What solemn sound the ear invades,

What wraps the land in sorrow’s shade?

From heav’n the awful mandate flies,

The father of his country dies.

Where shall our nation turn its eye,

What help remains beneath the sky?

Our friend, protector, strength and trust,

Lies low and mould’ring in the dust.

“Your trying to reduce all this to nothing more than syllable count is bizarre. I’m sorry!”

I’m not “trying” to do anything. I’m simply explaining to you the nomenclature. As the concerned website itself writes: “These songs have varying numbers of 8-syllable verses, but they do not have the iambic stress pattern that is characteristic of Long Meter.” They are still called 8s or 8,8,8,8 (as the website itself writes). And these are also categorized as 8,8,8,8

Life is the time to serve the Lord,

The time t’insure the great reward;

And while the lamp holds out to burn

The vilest sinner may return.

etc.

Albeit, these 8s are in Long Meter, as it’s called. The point is: if you want to identify a common hymn meter, count syllables. That’s the way they are categorized. Count the syllables to categorize them (then feet if you want to separate them according to meter). I mean, I don’t know what else to say? 8,8,8,8 means a hymn with 4 lines, eight syllables each, regardless of the meter. Though some may not be Long Meter, they are still identified by the number of syllables per line.

LikeLike