- May 18, 2009 – New Post : John Donne & Batter my Heart, His Sonnet

- May 10, 2009 – New Post : Bright Star by John Keats, His Sonnet

- April 1, 2009 – Shelley’s Sonnet: Ozymandias

- March 29, 2009 – Sir Phillip Sidney: His Meter and his Sonnets

- March 19, 2009 – John Donne & his Sonnet Death be not proud…

- Updated and expanded March 25, 2009 – Miltonic Sonnet, Nonce Sonnet, Links to Various Sonnet Sequences and additional Sonnets.

- After you’ve read up on Sonnets, take a look at some of my poetry. I’m not half-bad. One of the reasons I write these posts is so that a few readers, interested in meter and rhyme, might want to try out poetry. Check out Spider, Spider or, if you want modern Iambic Pentameter, try My Bridge is like a Rainbow or Come Out! Take a copy to class if you need an example of Modern Iambic Pentameter. Pass it around if you have friends or relatives interested in this kind of poetry.

- April 23 2009: One Last Request! I love comments. If you’re a student, just leave a comment with the name of your high school or college. It’s interesting to me to see where readers are coming from and why they are reading these posts. :-)

The Shakespearean Sonnet: Shakespeare’s Sonnet 129

The word Sonnet originally meant Little Song.

Sonnets are one of my favorite verse forms after blank verse. And of all the sonnet forms, Shakespearean is my favorite – also known as the English Sonnet because this particular form of the sonnet was developed in England. The Shakespearean Sonnet is easily the most intellectual & dramatic of poetic forms and, when written well, is a showpiece not only of poetic prowess but intellectual prowess. The Shakespearean Sonnet weeds the men from the boys, the women from the girls. It’s the fugue, the half-pipe of poetic forms. Many, many poets have written Shakespearean Sonnets, but few poets (in my opinion) have ever fully fused their voice with the intellectual and poetic demands of the form. It ‘s not just a matter of getting the rhymes right, or the turn (the volta) after the second quatrain, or the meter, but of unifying the imagery, meter, rhyme and figurative language of the poem into an organic whole.

I am tempted to examine sonnets by poets other than Shakespeare or Spenser, the first masters of their respective forms, but I think it’s best (in this post at least) to take a look at how they did it, since they set the standard. The history of the Shakespearean Sonnet is less interesting to me than the form itself, but I’ll describe it briefly. Shakespeare didn’t publish his sonnets piecemeal over a period of time. They appeared all at once in 1609 published by Thomas Thorpe – a contemporary publisher of Shakespeare’s who had a reputation as “a publishing understrapper of piratical habits”.

Thank god for unethical publishers. If not for Thomas Thorpe, the sonnets would certainly be lost to the world.

How did Thorpe get his hands on the sonnets? Apparently they were circulating in manuscript among acquaintances of Shakespeare, his friends and connoisseurs of his poetry. Whether there was more than one copy in circulation is unknowable. However, Shakespeare was well-known in London by this time, had already had considerable success on the stage, and was well-liked as a poet. Apparently, there was enough excitement and interest in his sonnets that Thorpe saw an opportunity to make some money. (Pirates steal treasure, after all, not dross.)

The implication is that the sonnets were printed without Shakespeare’s knowledge or permission, but no historian really knows. Nearly all scholars put 15 years between their publication and their composition. No one knows to whom the sonnets were dedicated (we only have the initials W.H.) and if it’s ever irrefutably discovered- reams of Shakespeare scholars will have to file for unemployment.

(Note: While I once entertained the notion that the Earl of Oxford wrote Shakespeare’s plays – no longer. At this point, having spent half my life studying Shakespeare, I find the whole idea utterly ludicrous. And I find debating the subject utterly ludicrous. But if readers want to believe Shakespeare was written by Oxford, or Queen Elizabeth, or Francis Bacon, etc., I couldn’t care less.)

Now, onto one of my favorite Shakespearean Sonnets – Sonnet 129.

The expense of spirit in a waste of shame

The expense of spirit in a waste of shame

Is lust in action; and till action, lust

Is perjured, murderous, bloody, full of blame,

Savage, extreme, rude, cruel, not to trust,

Enjoy’d no sooner but despised straight,

Past reason hunted, and no sooner had

Past reason hated, as a swallow’d bait

On purpose laid to make the taker mad;

Mad in pursuit and in possession so;

Had, having, and in quest to have, extreme;

A bliss in proof, and proved, a very woe;

Before, a joy proposed; behind, a dream.

··All this the world well knows; yet none knows well

··To shun the heaven that leads men to this hell.

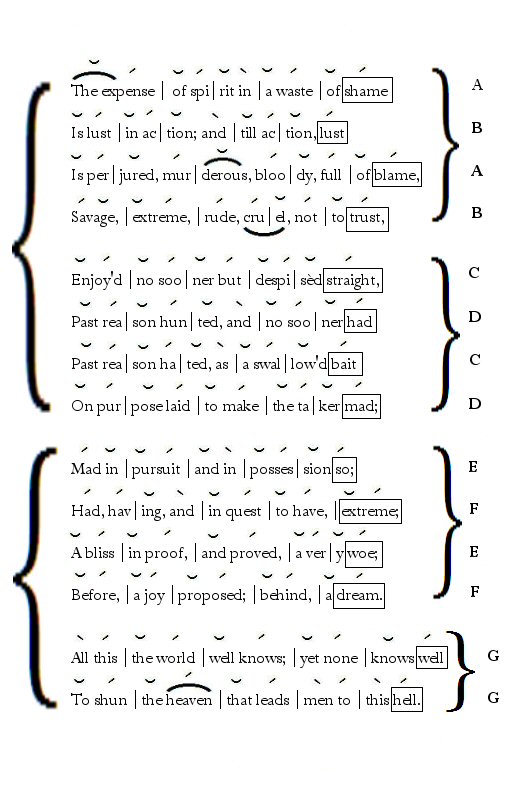

While this sonnet isn’t as poetic, figurative or “lovely” as Shakespeare’s most famous sonnets, it is written in a minor key, like Mozart’s 20th Piano Concerto, and beautifully displays the rigor and power of the Shakespearean Sonnet. Let’s have another look, this time fully annotated.

The Shakespearean Sonnet: Structure

First to the structure. Many Shakespearean Sonnets can be broken down, first, into two thematic parts (brackets on the left). The first part is comprised of two quatrains, 8 lines, called the octave, after which there is sometimes a change of mood or thematic direction. This turn (or volta) is followed by the sestet, six lines comprised of the quatrain and couplet. However, this sonnet – Sonnet 129 – does not have that thematic turn. There are plenty of sonnets by Shakespeare which do not.

In my experience, many instructors and poets put too much emphasis on the volta as a “necessary” feature of Shakespearean sonnet form (and the Sonnet in general). It’s not . In fact, Shakespeare (along contemporaries like Sidney) conceived of the form in a way that frequently worked against the Petrarchan turn with it’s contemplative aesthetic. The Elizabethan poets were after a different effect – as Britannica puts it: an argumentative terseness with an epigrammatic sting.

My personal analogy in describing the Shakespearean Sonnet is that of the blacksmith who picks an ingot from the coals of his imagination. He puts it to the anvil, chooses his mallet and strikes and heats and strikes with every line. He works his idea, shapes and heats it until the iron is white hot. Then, when the working out is ready, he gives it one last blow – the final couplet. The couplet nearly always rings with finality, a truth or certainty – the completion of argument, an assertion, a refutation.

Every aspect of the form lends itself to this sort of argument and conclusion. The interlocking rhymes that propel the reader from one quatrain to the next only serve to reinforce the final couplet (where the rhymes finally meet line to line). It’s from the fusion of this structure with thematic development that the form becomes the most intellectually powerful of poetic forms.

I have read quasi-Shakespearean Sonnets by modern poets who use slant rhymes, or no rhymes at all, but to my ear they miss the point. Modern poets, used to writing free verse, find it easier to dispense with strict rhymes but again, and perhaps only to me, it dilutes the very thing that gives the form its expressiveness and power. They’re like the fugues that Reicha wrote – who dispensed with the normally strict tonic/dominant key relationships. That made writing fugues much easier, but they lost much of their edge and pithiness.

And this brings me to another thought.

Rhyme, when well done, produces an effect that free verse simply does not match and cannot reproduce. Rhyme, in the hands of a master, isn’t just about being pretty, formal or graceful. It subliminally directs the reader’s ear and mind, reinforcing thought and thematic material. The whole of the Shakespearean rhyme scheme is hewed to his habit of thought and composition. The one informs the other. In my own poetry, my blank verse poem Come Out! for example, I’ve tried to exploit rhyme’s capacity to reinforce theme and sound. The free verse poet who abjures rhyme of any sort is missing out.

The Shakespearean Sonnet: Meter

As of writing this (Jan 10, 2009), Wikipedia states: “A Shakespearean sonnet consists of 14 lines, each line contains ten syllables, and each line is written in iambic pentameter in which a pattern of a non-emphasized syllable followed by an emphasized syllable is repeated five times.”

And Wikipedia is wrong.

Check out my post on Shakespeare’s Sonnet 145. This is a sonnet, by Shakespeare, that contains 8 syllables per line, not ten. It is the only one (that we know of) but is nonetheless a Shakespearean Sonnet. The most important attribute of the Shakespearean Sonnet is it’s rhyme scheme, not its meter. Why? Because the essence of the Shakespearean Sonnet is in its sense of drama. (Shakespeare was nothing if not a dramatist.) The rhyme scheme, because of the way it directs the ear, reinforces the dramatic feel of the sonnet. This is what makes a sonnet Shakespearean. Before Shakespeare, there was Sidney, whose sonnets include many written in hexameters.

That said, the meter of Sonnet 129 is Iambic Pentameter. I have closely analyzed the meter in Shakespeare’s Sonnet 116, so I won’t go too far in depth with this one, except to point out some interesting twists.

As a practical matter, the first foot of the first line |The expense |should probably, in the reading, be elided to sound like |Th’expense|. This preserves the Iambic rhythm of the sonnet from the outset. Unless there is absolutely no way around it, an anapest in the first foot of the first line of a sonnet (in Shakespeare’s day) would be unheard of.

Lines 3 and 4, of the first quatrain, are hard driving, angry Iambs. Murderous in line 3 should be elided, in the reading, to sound like murd‘rous, but the word cruel, in line 4, produces an interesting effect. I have heard it pronounced as a two syllable word and, more commonly, as a monosyllabic word. Shakespeare could have chosen a clearly disyllabic word, but he didn’t. He chooses a word that, in name, fulfills the iambic patter, but in effect, disrupts it and works against it. Practically, the line is read as follows:

The trochaic foot produced by the word savage is, in and of itself, savage – savagely disrupting the iambic patter. Knowing that cruel works in a sort of metrical no man’s land, Shakespeare encourages the line to be read percussively. The third metrical foot is read as monosyllabic – angrily emphasizing the word cruel. The whole of it is a metrical tour de force that sets the dramatic, angry, sonnet on its way.

There are many rhetorical techniques Shakespeare uses as he builds the argument of his sonnet, many of them figures of repetition, such as Epanalepsis in line 1, Polyptoton, and anadiplosis (in the repetition of mad at the end and start of a phrase): “On purpose laid to make the taker mad;/Mad in pursuit”. But the most obvious and important is the syntactic parallelism that that propels the sonnet after the first quatrain. The technique furiously drives the thematic material forward, line by line, each emphasizing the one before – emphasizing Shakespeare’s angry, remorseful, disappointment in himself – the having and the having had. It all drives the sonnet forward like the blacksmith’s hammer blows on white hot iron.

And when the iron is hot, he strikes:

All this the world well knows; yet none knows well

To shun the heaven that leads men to this hell.

The intellectual power displayed in the rhetorical construction of the sonnet finds its dramatic climax in the final couplet – the antimetabole of “well knows” and “knows well” mirrors the parallelism in the sonnet as a whole – succinctly. The midline break in the first line of the couplet is resolved by the forceful, unbroken final line. The effect is of forceful finality. This sonnet could have been a monologue drawn from one of Shakespeare’s plays. And this, this thematic, dramatic momentum that finds resolution in a final couplet is what most typifies the Shakespearean Sonnet. The form is a showpiece.

Lastly, I myself have tried my hand at Shakespearean Sonnets. My best effort is “As on a sunny afternoon…”. Three more of my efforts can be found if you look at the top of the banner- under Index: Opening Book (my favorite of the three being The Farmer Wife’s Complaint. I learned how to write poetry by writing Sonnets. I’ve written many others but their quality varies. I may eventually post them anyway.

- Shakespeare’s Sonnets Online can be found at Shakespeare-Online.Com

- Samuel Daniel Delia: Daniel’s Sequence is written in the Shakespearean mode.

- Michael Drayton’s IDEA is also written in the Shakespearean mode.

- For a modern Sonnet Sequence with a humorous bent (including Shakespearean Sonnets, consider Robert Graber’s Plutonic Sonnets.

The Spenserian Sonnet: Spenser’s Sonnet 75

The Spenserian Sonnet: Spenser’s Sonnet 75

Spenser has to be the most doggedly Iambic of any poet – to a fault. Second only to his dogged metrical Iambs, is his rhyming. English isn’t the easiest language for rhyming (as compared to Japanese or Italian). Rhyming in English requires greater skill and finesse, testing a poet’s resourcefulness and imagination. Yet Spenser rhymed with the ease of a cook dicing carrots. Nothing stopped him. His sonnets reflect that capacity – differing from Shakespeare’s mainly in their rhyme scheme. Here is a favorite Sonnet (to me) his Sonnet 75 from Amoretti:

One day I wrote her name upon the strand,

··But came the waves and washed it away:

··Again I wrote it with a second hand,

But came the tide, and made my pains his prey.

Vain man, said she, that doest in vain assay

··A mortal thing so to immortalize,

··For I myself shall like to this decay,

And eek my name be wiped out likewise.

Not so (quoth I), let baser things devise

··To die in dust, but you shall live by fame:

··My verse your virtues rare shall eternize,

And in the heavens write your glorious name.

··Where whenas Death shall all the world subdue,

··Our love shall live, and later life renew.

The Elizabethans were an intellectually rigorous bunch, which is one of the reasons I enjoy their poetry so much. They don’t slouch or wallow in listless confessionals. They were trained from childhood school days to reason and proceed after the best of the Renaissance rhetoricians. Spenser, like Shakespeare, has an argument to make, but Spenser was less of a dramatist, and more of a lyricist and storyteller. His preference in Sonnet form reflects that. Here it is – the full monty:

The Spenserian Sonnet: Structure

The difference in temperament between Spenser and Shakespeare is revealed in the rhyme scheme each preferred. Spenser was a poet of elegance who looked back at other poets, Chaucer especially; and who wanted his readers to know that he was writing in the grand poetic tradition – whereas Shakespeare was impishly forward looking, a Dramatist first and a Poet second, who enjoyed turning tradition and expectation on its head, surprising his readers (as all Dramatists like to do) by turning Patrarchan expectations upside down. Spenser elegantly wrote within the Petrarchan tradition and wasn’t out to upset any apple carts. Even his choice of vocabulary, as with eek, was studiously archaic (even in his own day).

Spenser’s sonnet lacks the drama of Shakespeare’s. Rather than withholding the couplet until the end of the sonnet, lending a sort of climax or denouement to the form, Spencer dilutes the effect of the final couplet by introducing two internal couplets (smaller brackets on right) prior to the final couplet. While Spencer’s syntactic and thematic development rarely emphasizes the internal couplets, they are registered by the ear and so blunt the effect of the concluding couplet.

There is also less variety of rhyming in the Spenserian Sonnet than in the Shakespearean Sonnet. The effect is of less rigor and momentum and greater lyricism, melodiousness and grace. The rhymes elegantly intertwine not only the quatrains but the octave and sestet (brackets on left). Without being Italian (Petrarchan) the effect which the Spencerian Sonnet produces is more Italian – or at minimum a sort of hybrid between Shakespeare’s English Sonnet and Pertrarch’s “Italian” model.

Spencer comes closest, in spirit, to anything like a Petrarchan Sonnet sequence in the English language.

The Spenserian Sonnet: Spenser’s Meter

As far as I know, Spenser wrote all of his sonnets in Iambic Pentameter. He takes fewer risks than Shakespeare, is less inclined to flex the meter the way Shakespeare does. For instance, in two of the three Shakespeare sonnets I have analyzed on this blog, Shakespeare is willing to have the reader treat heaven as a monosyllabic word (heav’n) (see my post on Shakespeare’s Sonnet 145 for an example of Shakespeare’s usage along with sonnet above). Spencer treats heaven is disyllabic. Their different treatment of the word might reflect a difference in their own dialects but I’m more inclined to think that Shakespeare took a more flexible approach to meter and pronunciation – less concerned than Spenser with metrical propriety. Shakespeare, in all things, was a pragmatist, Spenser, an idealist – at least in his poetry.

(Interesting note, Robert Frost referred to such metrical feet which could be anapestic or Iambic depending on the pronunciation, as “loose Iambs “. Such loose iambs would include Shakespeare’s sonnet where murderous could be pronounced murd’rous and The expense as Th’expense.)

There are two words which the modern reader might pronounce as monosyllabic – washed in line 2 and wiped in line 8. When reading Spenser, it’s best to assume that he meant his lines to be strongly regular. It is thoroughly in keeping with 15th & 16th century poetic practice (and with Spenser especially) to pronounce both words as disyllabic – washèd & wipèd. Spenser was a traditionalist.

I also wanted to briefly draw attention to the difference in Shakespeare and Spenser’s use of figurative language. Shakespeare was much more the intellectual. Nothing in Spenser’s sonnets compare to the brilliant rhetorical figures used by Shakespeare. Shakespeare was a virtuoso on many levels.

- Spenser’s Sonnets Online Amoretti

The Petrarchan Sonnet: John Milton

The Petrarchan Sonnet: John Milton

The Petrarchan Sonnet was the first Sonnet form to be written in the English Language – brought to the English language by Sir Thomas Wyatt and Henry Howard Earl of Surrey (who was also the first to introduce blank verse to the English writing world). However, there is no great Petrarchan Sonnet sequence that left its mark on the form. The Petrarchan model was quickly superseded by the English/Shakespearean Sonnet. Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Sonnet Sequence (all Petrarchan Sonnets) is mixed with greatness but never influenced the form. They were written toward the close of the form’s long history. For a link to her Sonnets, see below.

The search for the ideal representative, among English language poets, of the Petrarchan Sonnet is a search in vain. Petrarchan Sonnets are scattered throughout the language by a number of great poets and poets, who if they weren’t “great”, happened to write great Petrarchan Sonnets.

One thing I have failed to mention, up to now, is the thematic convention associated with the writing of Sonnets – idealized love. Both the Shakespearean and Spenserian Sonnet sequences play on that convention. The Petrarchan form, interestingly, was readily adopted for other ends. It was as if (since the English Sonnet took over the thematic convention of the Petrarchan sonnet) poets using the Petrarchan form were free to apply it elsewhere.

Since there is no one supreme representative Petrarchan Sonnet or poet, I’ll offer up John Milton’s effort in the form, since it was early on and typifies the sort of thematic freedom to which the Petrarchan form was adapted.

When I consider how my light is spent,

··Ere half my days in this dark world and wide,

··And that one talent which is death to hide

Lodged with me useless, though my soul more bent

To serve therewith my Maker, and present

··My true account, lest He returning chide;

··“Doth God exact day-labor, light denied?”

I fondly ask. But Patience, to prevent

That murmur, soon replies, “God doth not need

Either man’s work or His own gifts. Who best

Bear His mild yoke, they serve Him best. His state

Is kingly: thousands at His bidding speed,

And post o’er land and ocean without rest;

They also serve who only stand and wait.”

And here is the same Sonnet under the magnifying glass:

The Petrarchan Sonnet: Structure

My primary interest is in English language poets who have written in the Petrarchan form. However, for those who want a good site that examines Petrarchan Sonnets as written by Petrarch, I would strongly recommend Peter Sadlon’s site – he includes some examples in the Italian. He makes the point, for example, that Petrarch did not write Iambic Pentameter sonnets, since the meter is ill-suited to the Italian Language. More important is the observation that Petrarch himself varied the rhyme scheme of the sestet – cd cd cd (as in Milton’s Sonnet), cde ced, or cdcd ee.Petrarch’s freedom in the final sestet is carried over into the English form. You will know that you are reading a Petrarchan sonnet first, if it’s not Shakespearean or Spenserian, and second if the rhyme scheme favors the reading of an octave followed by a sestet. Identifying a Petrarchan sonnet sometimes isn’t an exact science. This beautiful sonnet form is less about the rhyme scheme and more about the tenor of expression.

Interestingly, even though Robert Frost’s famous sonnet “Silken Tent” is formally a Shakespearean Sonnet, it has the feel of a Petrarchan Sonnet.

As regards Milton, he wrote this sonnet as a response to his growing blindness. The sonnet has little to do with idealized love but its meditative and contemplative feel is very much in keeping with Petrarch’s own sonnets – contemplative and meditative poems on idealized love. The rhyme scheme reinforces the the sonnet’s introspection: enforcing the octave, the volta and the concluding sestet.

The internal couplets in the first and second quatrain (smaller brackets on right) give each quatrain and the octave as a whole a self-contained, self-sufficient feeling. The ear doesn’t register a step wise progression (a building of momentum) as it does in the Shakespearean & Spenserian models. The effect is to create a kind of two-stanza poem rather than the unified working-out of the English model.

Note: Perhaps a useful way to think of the difference between the Petrarchan and Shakespearean Sonnets is to think of the Petrarchan form as a sonnet of statement and the Shakespearean form as a sonnet of argument. Be forewarned, though, this is just a generalization with all its inherent limitations and exceptions.

The volta or turn comes thematically with God’s implied answer to Milton’s questioning. The lack of the concluding couplet makes the completion of the poem less epigrammatic, less dramatic and more considered. The whole is a sort of perfectly contained question and answer.

The Petrarchan Sonnet: Milton’s Meter

This sonnet was written prior to Paradise Lost and, to my ear, shows a slightly more adventurous metric. The first departure from the iambic rhythm comes in the first foot of line 4 with Lodged. This is the sort variation that perfectly exploits the expectations established by a metrical pattern. That is, the word works on two levels, “lodged” thematically and trochaic-ally within the iambic meter- not a brilliant variant but an effective one.

In line 5 I read the fourth foot as being pyrric, but one can also give the word and an intermediate stress: To serve therewith my Maker, and present.

It’s not until line 11 that things get interesting. Most modern readers would probably read the first two feet of the line as follows:

Bear His |mild yoke, |they serve Him best. His state

But the line can be read another way – iambically. And in poetry of this period, if we can, then we should.

Bear His |mild yoke, |they serve Him best. His state

What’s lovely about this reading, which is what’s lovely about meter, is that the inflection and meaning of the line changes. Notice also how His is emphasized in the first foot, but isn’t in the fourth and fifth:

Bear His |mild yoke, |they serve |Him best. |His state

In this wise, the emphasis is first on God, then on serving him. It is a thematically natural progression.

The last feature to notice is that the final line, line 14, retains a little of the pithy epigrammatic quality of the typical English or Shakespearean Sonnet. No form or genre is completely isolated from another. The Petrarchan mode can be felt in the Shakespearean Sonnet and the Shakespearean model can be felt in the Petrarchan model.

The Miltonic Sonnet

The Miltonic Sonnet is a Petrarchan Sonnet without a volta. Although Milton was hardly the first to write sonnets in English without a volta, Shakespeare’s Sonnet 129 being a case in point, Milton made that absence standard practice; and so, this variation on the Petrarchan Sonnet is called a Miltonic Sonnet.

On the Importance of Naming Things

Not only are there names for the different sonnets, which is forgivable, but there also names for the different quatrains and octaves in all these sonnets because human beings like nothing more than to classify. God’s first request to Adam & Eve was to name… everything. (What interests me more is puzzling out the aesthetic effects these different rhyme schemes produce.) But, because knowing the name of things always sounds impressive – here they are.

Petrarchan

The Petrarchan Sonnet can be said to be written with two Italian Quatrains (abbaabba) which together are called an Italian Octave.

The Italian Octave can be followed by an Italian Sestet (cdecde) or a Sicilian Sestet (cdcdcd)

The Envelope Sonnet, which is a variation on the Petrarchan Sonnet, rhymes abbacddc efgefg or efefef.

Shakespearean

The Shakespearean Sonnet is written with three Sicilian Quatrains: (abab cdcd efef) followed by a heroic couplet. Note, the word heroic refers to Iambic Pentameter. Heroic couplets are therefore Iambic Pentameter Couplets. However, not all Elizabethan Sonnets are written in Iambic Pentameter.

Spenserian

- Note: I have found no references which reveal when these terms first came into use. I doubt that the terms Sicilian or Italian Quatrain existed in Elizabethan times. Spenser didn’t sit down and say to himself: Today, I shall write interlocking sicilian quatrains. I think it more likely that these poets chose a given rhyme scheme because they were influenced by others or because the rhyme scheme was most suitable to their aesthetic temperament.

- Note: It bears repeating that many books on form will state that all these sonnets are characterized by voltas. They are, emphatically, not. Shakespeare’s Sonnet 129 (above) would be an example.

Other Petrarchan Sonnets

Since the Petrarchan Sonnet is so varied in the English Language tradition, I thought I would post a few more examples. I have divided the quatrains, octaves and sestets to better show their structure. I’ll probably come back to this post and include more as I find them. (For the most part, a couplet in the closing sestet seems, usually, to be avoided by most poets.)

John Keats

Rhyme Scheme:

ABBA ABBA CDCDCD (The same as Milton’s)

On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer

Much have I travell’d in the realms of gold,

Much have I travell’d in the realms of gold,

And many goodly states and kingdoms seen;

Round many western islands have I been

Which bards in fealty to Apollo hold.

Oft of one wide expanse had I been told

That deep-brow’d Homer ruled as his demesne;

Yet did I never breathe its pure serene

Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold:

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He star’d at the Pacific–and all his men

Look’d at each other with a wild surmise

Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

William Wordsworth

Rhyme Scheme:

ABBA ACCA DEDEDE

Surprised by joy — impatient as the Wind

Surprised by joy — impatient as the Wind

I turned to share the transport–Oh! with whom

But Thee, deep buried in the silent tomb,

That spot which no vicissitude can find?

Love, faithful love, recalled thee to my mind–

But how could I forget thee? Through what power,

Even for the least division of an hour,

Have I been so beguiled as to be blind

To my most grievous loss?–That thought’s return

Was the worst pang that sorrow ever bore,

Save one, one only, when I stood forlorn,

Knowing my heart’s best treasure was no more;

That neither present time, nor years unborn

Could to my sight that heavenly face restore.

Percy Bysshe Shelley

Rhyme Scheme:

ABAB ACDC EDEFEF

I met a traveller from an antique land

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: “Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. Near them on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown

And wrinkled lip and sneer of cold command

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed.

And on the pedestal these words appear:

`My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings:

Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!’

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare,

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

For a closer look at this sonnet, take a look at my post: Shelley’s Sonnet: Ozymandias

Edna St. Vincent Millay

Rhyme Scheme:

ABBA ABBA CDEDCE

What lips my lips have kissed, and where, and why,

What lips my lips have kissed, and where, and why,

I have forgotten, and what arms have lain

Under my head till morning; but the rain

Is full of ghosts tonight, that tap and sigh

Upon the glass and listen for reply,

And in my heart there stirs a quiet pain

For unremembered lads that not again

Will turn to me at midnight with a cry.

Thus in winter stands the lonely tree,

Nor knows what birds have vanished one by one,

Yet knows its boughs more silent than before:

I cannot say what loves have come and gone,

I only know that summer sang in me

A little while, that in me sings no more.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning

Rhyme Scheme:

ABBA ABBA CDCDCD

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of Being and ideal Grace.

I love thee to the level of everyday’s

Most quiet need, by sun and candle-light.

I love thee freely, as men strive for Right;

I love thee purely, as they turn from Praise.

I love thee with a passion put to use

In my old griefs, and with my childhood’s faith.

I love thee with a love I seemed to lose

With my lost saints, — I love thee with the breath,

Smiles, tears, of all my life! — and, if God choose,

I shall but love thee better after death.

- Elizabeth Barret Browning Sonnets from the Portuguese: The Sequence from which the Sonnet, above, comes.

Other Sonnets:

- Sir Philip Sidney Astrophel and StellaSidney’s sonnets are a kind of hybrid between the Shakespearean and Petrarchan mode. The Octave of his sonnets alternate between the Petrarchan Octave and the interlocking Sicilian Quatrains of the English Sonnets. His Sestets alternate between one of his own devising and the Shakespearean model. For more on this: visit my post Sidney: His Meter and Sonnets.

- John Donne Holy Sonnets These sonnets are like Sidney’s – having qualities of both the Shakespearean and Petrarchan form.

- And then there are sonnets of varying rhyme schemes – Nonce Sonnets. The word Nonce simply means that a given form is unique to the poem. Keats’ If by dull rhymes would be a Nonce Sonnet – and written specifically about the making of a new rhyme scheme.

John Keats

Rhyme Scheme:

ABCADE CADC EFEF

If by dull rhymes our English must be chain’d,

And, like Andromeda, the Sonnet sweet

Fetter’d, in spite of pained loveliness;

Let us find out, if we must be constrain’d,

Sandals more interwoven and complete

To fit the naked foot of poesy;

Let us inspect the lyre, and weigh the stress

Of every chord, and see what may be gain’d

By ear industrious, and attention meet:

Misers of sound and syllable, no less

Than Midas of his coinage, let us be

Jealous of dead leaves in the bay wreath crown;

So, if we may not let the Muse be free,

She will be bound with garlands of her own.

this is good for homework

LikeLike

this was extremely helpful in my miltonic sonnet assignment, as well as enjoyable to read. thanks!

LikeLike

Thankyou so much for commenting. It always makes the effort worthwhile.

LikeLike

thanks so much, you are a great writer and this was a tremendous help!

LikeLike

And thank you. If there are any improvements or questions I haven’t answered, please let me know.

LikeLike

Thankyou for the information. Very helpful for me to understand the differences between Spenserian Sonnets and Shakespearian Sonnets. :P

LikeLike

Really helpful… Great Resource!!!!!

LikeLike

Glad to hear it. I continue to add and revise based on responses and searches.

LikeLike

Thank you so much. This really helped me understand how the Spenserian sonnet is different yet similar to the others. It was a great help for my English final.

LikeLike

Thanks so much for your note – I really do appreciate it.

LikeLike

I love this site — I teach a high school course in Kentwood MI, and will recommend it to my students! Thank you!

LikeLike

That’s as high a compliment as I could hope for. : )

LikeLike

I found your site because I recently began producing poetry. It’s rather embarrassing, really, since I can’t tell if any of it is good. So I’m reading published poetry and related stuff to find out what makes good poetry. Your site has been a help. I’ll be spending a lot of time here in the coming weeks and months, I think.

LikeLike

I hope some of what I write is helpful. If you see mistakes or ways to improve, let me know. And if you have questions, be sure and ask. I get many of my ideas from the feedback of readers.

LikeLike

Pingback: Millay’s Sonnet 42 • What lips my lips have kissed « PoemShape

Pingback: Another Poet & Children’s Writer « PoemShape

Pingback: Donne: His Sonnet IX • Forgive & Forget « PoemShape

Pingback: Plutonic Sonnets by Robert Bates Graber « PoemShape

Hello I have throughly enjoyed reading your post, I too love shakespeare. At the moment I am trying to come up with a sonnet for my British Literature class and was having a hard time, but you have helped. I go to college in MS, am still wondering if this was such a great idea, after being out for 5 years. no matter my fears I have and therefore will finish. Thank you again for your post and I am sure I will be using it again.

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment, Tamara. The interaction of readers is what makes the effort rewarding.

LikeLike

A well researched essay.

LikeLike

Very stimulating, Patrick! I would like to register here, however, my reservations about the term “Shakespearean sonnet.” First, the form ababcdcdefefgg in iambic pentameter appears to have been invented not by the Bard but by Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey. Second, Shakespeare was not even first to adopt the form for an extended sonnet cycle; that honor goes to Samul Daniel for his “To Delia” (1592). Great people become what one might call “glory magnets,” accumulating credit for more–sometimes far more–than is their due. (I think it has to do with with something about them, and also with something about the rest of us…) In any case, the term “English sonnet,” though better, is misleadingly general; I hereby propose the euphonious “Surrian sonnet,” in honor of the form’s brilliant, ill-fated, and too-little-remembered inventor.

:-,?

LikeLike

You have quickly become my favorite guest. Here’s the thing about Daniel. He published his verses in 1592. Shakespeare’s Sonnets 138 & 144 first appeared in public in 1598-1599, the whole of them appeared in 1609, so at first blush it appears that Daniel anticipated Shakespeare by several years, if not a decade. But potential references to the sonnets first appear in Shakespeare’s own hand(!) in the recently recognized play Edward III.

In Eward III is found the following:

“lillies that fester smell far worse than weeds” [Act II.i – 808 Eric Sams Edition]

Edward III was first registered in 1595, but the publisher states that it had been acted in sundry locations and times. Scholars believe the play could have been written as early as 1588, which would be typical. The Oxford Shakespeare states that it could have been written “at any time between the Armada of 1588 and 1595”. Publishers didn’t usually publish plays until their popularity had been established. And if they did so on the sly, the text usually suffered for it. Edward III seems to be a fair copy and so the play was probably printed in collaboration with the players. If the order of the sonnets is to be believed, then the line borrowed from Sonnet 94 means that most of Shakespeare’s Sonnets had already been written when Daniel published his sonnets. On the other hand, it may also mean that Shakespeare borrowed from the play. My hunch, though, is that the former is more likely.

The bottom line is that nobody knows with any certainty, but I tend to lean toward an early dating – mid to late 1580’s through early 1590’s, with revision, perhaps significant, over the course of the 1590’s. What follows is some interesting reading. You’ll see that it’s possible to date Shakespeare’s earliest sonnet to 1583. And also, in reference to Daniel, he was a noted borrower, even among his peers. If there are echoes of Daniel in Shakespeare’s Sonnets, I find it more likely that there are echoes of Shakespeare in Daniel’s Sonnets – given Daniel’s proven track record of borrowing. So, I’m content to name the Sonnets after Shakespeare on chronological grounds. He also perfected it to a degree that inspired generations of poets. Likewise, although Haydn didn’t invent the Symphony (I think Sammartini wrote nearly a hundred before Haydn), Haydn is called the father of the symphony because he was the first to fully exploit its artistic potential.

But anyway, here’s some interesting reading:

LikeLike

I never saw it coming! It ought to have occurred to me that Daniel’s priority, in serving up a long sonnet cycle in Surrian form, was not beyond question; but it did not. Thanks for the eye-opener.

LikeLike

PS: I greatly enjoyed revisiting Spenser’s Sonnet 75. A great English-Lit prof. (at Indiana) alerted us students to the way in which this poem cleverly–if thinly– disguises the fact that the courtly poet’s verse serves incomparably less to immortalize his lady than himself! A few of my PLUTONIC SONNETS were inspired by this tradition, with its absurd exaggerations of the lady’s virtues, and the idle creation of silly little artificial puzzles to be wittily solved (or sidestepped) in the sestet. Such “conceits” surely include my Sonnet 113, which your review quotes in full; and though your critical analysis of that sonnet does score some points, I confess that it reminded me of what the anthropologist A.L. Kroeber called “breaking a butterfly on the wheel”!

LikeLike

the information are good.. :).. I didn’t had a hard time looking for my projects..

LikeLike

Grammar???

LikeLike

HI SMS, many readers here are not native English speakers. Besides that, I would rather enjoy a reader’s input than fuss over their typos and grammar. I appreciated her note.

LikeLike

you’re my hero.

LikeLike

Who, me??

:-,?

(User is puffing compacently on his briar–a bent shape, apparently…)

LikeLike

Notification request.

LikeLike

Thanks again – I will be referring my students to this site for sonnet help tomorrow in class. I can’t wait for them to see it!

LikeLike

Pingback: The world is too much with us ❧ William Wordsworth « PoemShape

Hello, thank you so much for this excellent essay on sonnets, it’s really a great help in my preparation for the French teacher’s competition.

LikeLike

Hey Erie! Thanks for the comment. It’s nice to get a little pat on the back every now and then.

LikeLike

What part of the Petrarchan sonnet remained after it was taken over by the Elizabethan era?

LikeLike

Also, where is this information found?

LikeLike

As far as I know, there is no formal study of the Petrarchan Sonnet’s transformation at the hands of the Elizabethans. It’s frequently commented on and described, but never analyzed or examined. My own writing on this blog, especially as regards Sidney and this post, might be as close as you’ll come. If any such study is done, then Sidney (and his circle of poets) would be a central figure. You can see that Sidney was dissatisfied with the Patrarchan form (they all were) and was feeling his way toward a more suitably Elizabethan rendition. It didn’t take long – 1570’s to 80’s. By the 1590’s the first sonnet cycles were being published and many poets, like Daniel, Shakespeare and Spenser, had settled on schemes that suited their own temperament and the temperament of the times – rhetorical, dramatic and witty.

What remained?

1.) 14 Lines.

2.) The volta survived… somewhat.

3.) Most importantly, the epistolary feel of the sonnets. I can’t think of any Elizabethan poet who didn’t treat them like little soliloquies – pieces of dialog. One doesn’t find the dreamy, introverted utterances of the Romantics.

5.) Subject matter – love and unrequited love remained the most popular thesis of Elizabethan poets. Shakespeare, ever the playful genius, turned the genre’s expectations on it’s head. There are some essays on this subject. However, I looked through my collection of Shakespeare criticism and couldn’t find anything. Mostly, you will find such writing in the Shakespeare Survey. Lucky for you (and me), and if you really want to pursue this, Cambridge is now releasing back issues as paperbacks. (What the heck took them so long?) That said, the very best place to look is in the introductions to the various editions of Elizabethan Sonnets – Shakespeare’s, Spenser’s, Daniel’s, Sidney’s, Donne’s, etc…

The other thing to know is that before the sonnet was adopted there was no standardized short form with which poets could measure themselves and measure themselves against each other.

Interesting question though, I might have to think more about it.

LikeLike

“Against each other”–an excellent point! Remarking on the comparative difficulty of writing Spenserian sonnets, I asked an erudite friend why people would adopt a demanding rhyme scheme that so far “undoes” the achievement of Surrey in creating a versatile, flexible sonnet form for a rhyme-stingy language like English. He replied, in effect, to show they could do it! This fits well with the importance that demonstrating one’s wit played among the Elizabethan courtly poets. One might suggest: What’s sauce for the substance is sauce for the form.

LikeLike

Thank you for your reply. This is a question that has boggled my mind and research. The only thing I can find that remained was the rhyme scheme.

LikeLike

for the scansion of Milton’s “When I Consider How my Light is Spent”, do the boxed words signify the rhyming words? Or is it also endstopping. It would be nice if you could add where the caesura’s/enjaments/ and endstopping occur within the poem.. I’m having a little trouble figuring that part out.

LikeLike

Yes.

These are all easy. A Caesura is simply a break in thought anywhere within the line (as opposed to the end of the line). Look for punctuation. A pause in thought is always (to my knowledge) indicated by punctuation. Periods (.), exclamation points (!), question marks (?) or etc’s (…) usually always mark a Caesura, as in the following line:

I fondly ask. // But Patience, to prevent

Dashes (-), colons (:) and semicolons (;) can (but not always) indicate a Caesura. If one stops when we read them, then they are probably Caesuras. If one only pauses, then they probably aren’t. Commas (,) may or may not. If you’re not sure, read the line aloud. If you can read the line without too much of a pause or without stopping (and it makes sense and doesn’t sound hurried) then there’s no Caesura. If a comma makes you want to pause (linger) or stop (in order to make sense of a line) then it’s a Caesura. It’s not a science. It’s somewhat subjective.

Endstopping is also easy to identify. It’s nothing more than a Caesura at the end of the line. Enjambment is the opposite. There is no Caesura at the end of the line. (What gets tricky is when poets, two, three, and four hundred years ago, don’t punctuate the way we do. That means you have to read the line aloud and if you pause at the end of line, it’s not enjambed.

So:

When I consider how my light is spent, //

Ere half my days in this dark world and wide, //

And that one talent which is death to hide //

[Notice that I wouldn’t consider the line above enjambed. This is because Milton didn’t punctuate an appositive. In other words, we would normally write: And that one talent[,] which is death to hide[,] where the phrase “which is death to hide” modifies the noun talent. When you read the line you will naturally want to pause after talent, otherwise it sounds rushed.

Lodged with me useless, though my soul more bent

To serve therewith my Maker, and present

My true account, lest He returning chide; //

“Doth God exact day-labor, light denied?” //

I fondly ask. But Patience, to prevent

That murmur, soon replies, “God doth not need

Either man’s work or His own gifts. Who best

Bear His mild yoke, they serve Him best. His state

Is kingly: thousands at His bidding speed, //

And post o’er land and ocean without rest; //

They also serve who only stand and wait.”

//indicates end-stopped lines. Notice that all but one of them are punctuated. The other lines are enjambed.

What follows is what I might consider Caesura:

When I consider how my light is spent,

Ere half my days in this dark world and wide,

And that one talent which is death to hide

Lodged with me useless, though my soul more bent

To serve therewith my Maker, and present

My true account, lest He returning chide;

“Doth God exact day-labor, light denied?”

I fondly ask. // But Patience, to prevent

That murmur, soon replies, “God doth not need

Either man’s work or His own gifts. //Who best

Bear His mild yoke, they serve Him best. //His state

Is kingly: // thousands at His bidding speed,

And post o’er land and ocean without rest;

They also serve who only stand and wait.”

I wouldn’t consider the commas in the first and second quatrain Caesuras. One pauses, but doesn’t really stop.

LikeLike

Wow, thank you for your thorough explanation. Sometimes I over think the Caesura’s and place one where there isn’t one. This was extremely helpful. I’m writing about petrachan sonnets and I’ve come to realize that almost all of them stray away from traditional form in one way or another, whether it be frequent use of enjambment, caesura, or metric substitution. I’m comparing this piece, as well as Donne’s “Holy Sonnet 9” and Yeats’ “Leda and the Swan” to the original petrachan sonnets of Francesco Petrarch himself. I’d love to hear your thoughts on this if you have any at all.

Also on a side note you referred to Milton as Donne when you wrote : “[Notice that I wouldn’t consider the line above enjambed. This is because Donne didn’t punctuate an appositive.”

Just wanted to clear that up incase it confused any readers…

Thank you once again for all your brilliant work!

LikeLike

One thing I’ve always wondered, but never investigated, is whether (over time) the Patrarchan form was more favored by female poets and the English (Shakespearean) Sonnet more favored by men. For some reason the Patrarchan Sonnet has always felt more feminine and the Shakespearean more masculine. Why? Maybe because the Petrarchan feels like it’s more about emoting and feeling and the Shakespearean Sonnet is more about argumentation and intellectual showmanship. The most famous works in the English Sonnet form seem to be by men and the most famous Patrarchan forms seem to be by women.

But… I could be wrong.

As to straying from the traditional form, here are my thoughts: Petrarch’s own Sonnets were the sine qua non (do I sound educated or what?) of the Petrarchan Sonnet form – hence the reason they are called Patrarchan. Elizabethan poets, among other reasons, might not have wanted to compete with Petrarch by adopting his rhyme scheme. It’s interesting that Sidney, (Shakespeare, Daniel, and Drayton) and Spenser each wrote sonnet cycles using original variations on the sonnet. It worked. Rather than being poets who wrote Petrarchan sonnets (which might also have felt fusty and antiquated), they established their own (modern) tradition and identity. We now call their sonnets Spenserian, Shakespearean, and Sidneyan.

Lastly, they wouldn’t have thought of Petrarch’s Sonnets as a “Petrarchan (T)radition”. He was just a famous Italian poet whose fame they wanted to emulate. There was no “tradition”. In other words, they wouldn’t have thought in terms of “straying away. (Likewise, there were also no rules pertaining to enjambment, Caesuras, or meter. Meter was brand-spanking new and they were making up the rules as they went along.) The question is probably not: How did they stray away from Petrarchan Sonnets? but: What captivated them about the form and subject matter? Why did they want to emulate it or recreate it in their fashion? I would try to answer that by looking at the forms they adopted (which is sort of what I did in the post above).

I also wonder how familiar Yeats might have been with Petrarch? Worth knowing about is a letter from Yeats, February 7, 1904. He writes in a letter to Agnes Tobin (of her translation of Petrarch): “I have read it over & over. It is full of wise delight–things of tears and ecstacy”. However, Yeats didn’t speak Italian. If he was familiar with Petrarch then it was only through translation and if he was familiar with the “tradition” of Petrarchan Sonnets, then it was only the English language tradition he could read. In other words, I would assume that he was more influenced by the Petrarchan Sonnets of older English poets (who were themselves influenced by English language poets) than by Petrarch himself. Petrarch’s direct influence on our own poetry was probably exceptionally brief and in the person of Sir Thomas Wyatt. Milton spoke Italian and wrote some poets in Italian, but when he writes Sonnets in English he seems far more influenced by the Sonnets of his peers and the Elizabethans.

And thanks for the correction! Grazi!

Keep writing! I enjoy the conversation. This is an education for me as much as anyone else.

LikeLike

Hey dude — nice site! Thanks for the helpful info! I’m reading out of interest and I thoroughly enjoyed it! Oh and as for your request, I’m a student at Columbia University.

Cheers!

LikeLike

I like how he broke the poems down and explaned how they construct themselves and whether its dramatic or non dramatic.

this website is awesome !

LikeLike

Pingback: The Sheaves by Edwin Arlington Robinson « PoemShape

thank you that was helpful

I am studying English literature and I am in the first year that‘s really help me

thank you so much

LikeLike

Glad the post was helpful Nancy. :-)

LikeLike

that‘s me again

I’m from syria and as for your request, I’m a student at AL BAATH University.

LikeLike

Thanks so much! I’m going to Google Al Baath University and see what it looks like. The Internet makes the world a small place doesn’t it? Stay safe, Nancy. :-)

Does that look familiar? There aren’t many images of the university online.

LikeLike

you‘re right yes it does and thank your interest

this photo to university at Homms but mine it‘s at Hama

LikeLike

I have so many mistakes in my writing please excuse me cause I‘ll try to improve my level in writing

LikeLike

You’re doing very well. I’ve also studied foreign languages and have taught English as a foreign language. :-)

I looked for images of Al Baath at Hama but couldn’t find any. I’m just happy to know life goes on (and with a little bit of poetry). I really do wish you the best. Whatever kinds of questions you have, just let me know.

LikeLike

that‘s my college in Hama

LikeLike

that‘s kind of you I wish you the best too

that‘s photo to my univesity at Hama

LikeLike

Thanks Nancy. :-) For some reason your latest E-Mail was dumped in my SPAM folder. So sorry! Just found it. I tried to connect to the website (with the image) but it’s being blocked. I’ll try again this evening or tomorrow.

LikeLike

this image to my university at Hama

if you want to look for it write the second college faculty of arts

LikeLike

Hello. I am a student at Baylor University and I am studying sonnets, and in the midst of my search for information, I stumbled upon your blog.

It (seems to be at least) very informative. Thanks for making the guide on the side… It made it easier to peruse the info.

But heads up on the origin of the sonnet- according to some research I’ve done, it actually never meant “little song.” If you can get ahold of a copy of this article: “The Origin of the Sonnet” by Paul Oppenheimer, you’ll be able to get more information.

Cheers! And happy poetry writing to you.

LikeLike

Thanks Anon, I’ll look up the article at Dartmouth. Whatever’s newsworthy, I’ll pass along; add it to the post.

LikeLike

Update: I got a hold of the article and have just read it. Oppenheimer’s argument is odd. He writes:

There are certainly scholars who “assumed” this to be the case, but Oppenheimer’s generalization is more than a little condescending. Not all scholars assumes this to be true; that is, I doubt Oppenheimer is the first scholar to have actually investigated the matter.

But Oppenheimer doesn’t leave it at that, he then goes on:

And that, really, is what Oppenheimer seems to be taking issue with. He argues that the Sonnet’s origins are not in song (in the sense that they were originally not meant to be performed musically). He argues that they are actually an early departure from “poetry as lyric” (or poetry as musical performance). Sonnets were intended to be meditative. Therefore, he reasons, the word Sonnet was unlikely to have sprung from the word suono since, as he believes “on the weight of evidence” that they were never meant to be musically performed. (All of his argument, it should be noted, is heavily qualified with words like may, and might, might have and possibly.)

And Oppenheimer may be right, but his argument may nevertheless have nothing to do with the root of the word sonnet. He seems to make the assumption (or adopt the argument of other critics) that just because the word itself may have sprung from a word meaning “song” or “noise”, that the original sonnets must have been performed with musical accompaniment. This seems to assume that Renaissance poets were incapable of figurative language.

After all, he ignores (or chooses not to address) the possibility that one might call a poem “a little song” without the expectation that it would be performed as a song. Consider the word Poem. It comes “from the Greek poema, a noun derived from the verb poie-o, to make or do. Poets are often called makers.” If we take Oppenheimer’s argument at face value, it means that the Greeks didn’t write their poems, but made them (whatever that means). But the Greeks were using the word figuratively. Likewise, I don’t think that Oppenheimer’s argument is complete until he considers the possibility that the appelation “little song” was being used figuratively.

LikeLike

hi i’m shasha from sri lanka

really a great help and you are a great writer

LikeLike

Thank you Shasha! :-) I’ve never been to Sri Lanka. Is it as beautiful as it looks in the picture books?

LikeLike

Hi thanks for your words for me in your page.

Sri Lanka is a beautiful country. If you see my country you you’ll write a book of poems, about the beauty of my country.

LikeLike

who first borrowed shakespearian sonnet from Italian sonnet form?

LikeLike

Nobody. The Shakespearian Sonnet wasn’t “borrowed” from the Italian Sonnet form. They are two different forms. :-)

LikeLike

I enjoyed this and plan to use it in my teaching. As we are going to Common Core, the discovery of your work could not have come at a better time. You have written this so it is easily understood and for my 9th graders, even this understanding will be a challenge for some–thank you:)

LikeLike

Thanks Anon, writing to be understood matters. Glad this post is helpful that way. Let me know, if you think of it, how your 9th graders get along with it.

LikeLike

Thank you! :) for all the help..

– student from St. Xavier’s College, Mumbai, India

LikeLike

Thank you very much for writing this. I’m at an early stage in my English career and this was really useful in learning some analysis skills for when I’m lookin at poetry.

LikeLike

Hello, I come from Greifswald University in Germany.

My professor actually recommended your page and now I am writing and term paper (on natural imagery in Shakespeare’s sonnets) and looking up his recommended reading.

LikeLike

Thanks Mom. That’s quite a compliment.

LikeLike

Pingback: On the subject of Rhyming « PoemShape

hello from Russia)

that is great work, thank you for that.

hope you will post commentaries to other sonnets too, it is very helpful for student’s work.

LikeLike

Hello Russia! I hope you will visit Vermont someday. I’m always on the lookout for which sonnets students are interested in.

LikeLike

Extremely useful, Im an english lit student at university in england. It was really helpful and succinctly explained. :)

LikeLike

Thanks Anon!

LikeLike

Thanks from Serbia, this is exactly what I need for my seminar paper on Shake-speares Sonnets. It’s great that you have so many examples on iambic pentameter and stressed/unstressed syllables.

LikeLike

The irony is too much; I have the whole world’s internet ideas at my disposal, and I find the best piece by an author from my own state. Great work on this.

I was wondering if there were any articles/journals/other resources you referenced or recommend, particularly about juxtaposing Shakespeare and Spenser.

Gratefully, a very proximate reader

LikeLike

You know… not really. I can’t think, off hand, of any articles or journals that I would recommend. Writing this was, for me, an attempt to write the kind of article I wasn’t finding else where. I can’t imagine I’m the first to write an article like this, but maybe I am? One usually finds these sonnets individually defined in a variety of poetry dictionaries (I can give you a list if you like) but I never see them specifically juxtaposed. In writing the post I drew on my own experience. (I learned how to write poetry by writing Sonnets.) I studied them assiduously. Insofar as the comparisons go, the opinions and observations are entirely my own. It’s all original work.

I’m going to be offering a class at the Writing Center in White River Junction. At the moment, I’m debating where to start. I may start with sonnets? I also love haiku. We Vermonters are just so cool. Check out this video and wait for “Miss Vermont” to show up. It’s so true. :)

LikeLike

Love that clip. And I loved the real Miss VT’s original response about evolution just as much! Best of luck with your class, your students will be very fortunate to have you. Wish I was a bit closer to WRJ. :)

LikeLike

Awesome blog you have here but I was wondering if you knew of any user discussion forums that cover the same topics talked

about in this article? I’d really love to be a part of online community where I can get advice from other experienced people that share the same interest. If you have any suggestions, please let me know. Thanks a lot!

LikeLike

Hi Felica, you might try visiting a site called Able Muse or here. I recommend it warily. My experience with Eratosphere has been very mixed. At worst, it is very cliquish, boorish and catty (and the most experience members can be very mediocre). However, there are members who have been there for years and enjoy it. Your experience might be different from mine. Other than that, a quick Google search turned up some possibilities but none that I’m familiar with. Discussion forums are always problematic. The experienced writers and poets don’t tend to stick around. However, you are welcome to write me any time. I’m very friendly. :-)

LikeLike

Hello! I’m a first-year student from Presidency University, Kolkata, India. Classes just began a month ago, and we received our first assignment on Shakespearean sonnets: to elaborate using one sonnet, how Shakespeare’s style differed from Petrarch and Sydney. Needless to say, that’s not very simple for newbies like us, but I read your analysis of Sonnet 145, Sonnet 129, and Sonnet 116, really helped a lot! I now have a much better idea how to go about my task, thank you so much!

LikeLike

Thank you for your note Samriddhi! I never could have guessed that someday students from India would be reading these posts. I feel very fortunate; and I couldn’t be happier that the post is helpful.

LikeLike

Who write this he must be a good writter. He can describe all types of sonnet in a perfect way and this help me so much.

LikeLike

Pingback: On Robert Frost’s After Apple-Picking « PoemShape

This article was a great help for preparing my tutorial in English Literary Studies. I will recommend this website to my 1st semester students. Greetings from Technical University Chemnitz

LikeLike

Thanks Haarpunzel. It’s always nice to know that an article has been helpful. Encourages me to write more. :-)

LikeLike

Thank you soooo much! I searched for 2 hours why one line in my sonnet had an extra syllable and only after your analysis of Sonnet 129 did I realize it was a dipthong! I am analyzing the sonnet “Beauty and Desire” by Edward Thurlow!

LikeLike

Glad the post helped you Kevin! Reading Edward Thurlow? That’s a poet I haven’t looked at in years. Byron let Thurlow have it, apparently. Have you seen this? Pity the man who ran afoul of Byron…

LikeLike

Hi, This helped me out so much in writing my senior research paper on the differences between Shakespearean and Spenserian sonnets

LikeLike

Reblogged this on adoraphobia and commented:

I was so inundated by my readings and papers for my Literature course–and so I geeked out and tried to search for every possible reference I may get–lo and behold, I found this. This made my day. So happy to have found this blog! *kisses and hugs and kisses and some more hugs to the author*

LikeLike

Pingback: Metrical Poems are a Carnival Ride | Border and Greet Me

In Spenser’s “Faerie Queene” his sonnets are nine lines long, not the three quatrains and a couplet that you mentioned.

LikeLike

Hi Jocelyn — Yes, the stanzas of the Faerie Queene are nine lines long, but they aren’t sonnets. As far as I know, I never referred to them as sonnets. If I did though, then I was wrong. His collection of poems in Amoretti, on the other hand, are sonnets. :-)

LikeLike

hi. thanks a lot for this. makes a huge difference in my half semester project!

LikeLike

Pingback: Five Relics From My Adventures As A High School English Teacher | The L. Palmer Chronicles

Where can I find the sources?

LikeLike

To what?

LikeLike

Pingback: Yeats’ Byzantium « PoemShape

The

Waterford School

LikeLike

This was of such immense help. And also very enjoyable to read. I am studying literature in Delhi University. I am loving your blog and it seems like I’ll be reading a lot more content in the coming days. :)

LikeLike

Dehli University? Wow. I’ve been to Dehli, but that was a long time ago — and when I was a child. Welcome! And I’m glad my posts are helpful. :-)

LikeLike

Hi, My name is Jo Ami, i am currently a student at Anglia Ruskin in Cambridge Studying English Literature, these articles/blogs have helped me immensely! Thank you so much!

LikeLike

Hi Jo Ami, thanks for making my evening. I love comments like yours. :-) I was just looking at the Wikipedia entry for your school — I like the architecture there. Looks like a nice school.

LikeLike

Excellent site! Bookmarked it for the future. Found you because I was trying to figure out meter for a Petrarchan sonnet. Looking forward to reading the rest of the blog as time permits. ~Jenna, Central Western University (Writing Specialization major).

LikeLike

Cool! Thanks. :-) What’s a “Writing Specialization” major?

LikeLike

It’s a brand new major, for people who are aiming to write for a living rather than writing as part of another job (does that make sense?). I am hoping to someday write the next Great American Novel :-).

PS Decided after reading your comments to write in the Shakespearean style instead.

LikeLike

Well, I’m snowed in today, so I saw your comment pop up. Sarah Lawrence had a creative writing “major”, sort of, but I wish your major had been around when I was in College. That’s really cool. I’ve never seen any justification for MFA’s in writing — complete rubbish in my opinion. But an undergraduate degree sounds great. You can pursue writing and get a degree. What’s better?

I’m working on the next great American novel too. If you ever want to exchange MS’s for a second opinion, let me know. :-) I’m still pursuing my dreams too.

LikeLike

Your site is just gorgeous! Interesting, informative, imaginative, funny, uplifting, inspiring. A fantastic resource for teachers and students, all poets and anyone with an interest in poetry.

A heartfelt thank you.

Nelly B, Cambridge, UK

LikeLike

Thanks Nelly, what a wonderful comment. :-)

LikeLike

Thomas G. Kuhn writing from Las Vegas, NV. Love your blog. Was trying to find some helpful definitive examples, of all kinds of sonnets. I am currently working on a sonnet sequence of my own. I have tended not to stop rhyming, for as you say it is the one thing that really keeps the form a sonnet. But within that form (the rhyming and the fourteen lines) there are huge variations . e.e.cummings, Sylvia Plath and Pablo Neruda to name just a few.Since all of the poets herein mentioned have made adjustments to give it “their own stamp” I decided to create my own fourteen line form, yet not vary it so much that it is not recognized as a sonnet. It has fourteen lines and a rhyming form. But I purposely did not want to use that form only. And I wanted to be able to answer the naysayer purists who might try to accuse me of not being capable of writing a strict shakespearian or petrarcan sonnet. So I deliberately have included several of each in my sequence. Sylvia Plath is really informative, because she honed her writing skills by writing hundreds of sonnets throughout her life and it helped make her blank verse have structure, with no wasted words. Thank you for the blog

LikeLike

First, you’re welcome. :-) Second, finding that sweet spot where a sonnet is still a sonnet, but new, is never easy. I understand the impulse to “reformulate” the sonnet through structure, but it’s hard for me to see how much more variation the sonnet can withstand. I know there will be partisans who recoil in horror at the thought that the sonnet can’t be infinitely varied, renewed and re-imagined by each generation, but the poem is only 14 lines long. Frost made the comment that he preferred the old-fashioned way to be new (a statement loaded with ironies); and I’m in that school. I can’t think of anything novel having been with the sonnet in decades. Anything new has had more to do with subject matter than with form, I think. Feel free to share your sonnets if you post them — provide a link. I’m always curious.

LikeLike

Vermont, I tried to channel Sylvia Plath by way of your response. Would this pass as one of her sonnets? It’s 14 lines and includes a volta but is written in free verse. Is that ever permissible with a sonnet?

Carpenter (by Sylvia Plath)

Ouch!

Knuckle scuffs the fence pale,

The splinter in or out?

In: a distal pus distracts

Out: a rotting corpse.

Salvation serendipity,

He’ll find it where he can

And now he buys his boards

Unmilled and chafes

The rougher side.

The beauty of his knuckle bones

Gristle gray, some oozing red.

Morning scabs do not withstand

His trips to Home Depot.

LikeLike

well… I personally wouldn’t consider it a sonnet, but there are plenty who would — anything with fourteen lines. :-)

LikeLike

Thanks. I said free verse, but seeing how I can read it to the tune of “Gilligan’s Island” it’s really more iambic than I had thought. I think I’ll rename it and drop it in my “collected poems.” The parody of the last two lines may be a little much for readers who take her very seriously. While she had her talents, too much of a Johnny one-knuckle for my taste. Too bad she didn’t like an occasional sweet with her Drano.

Sylvia Plath, Carpenter

Ouch!

Knuckle scuffs the fence pale,

The splinter in or out?

In: a distal pus distracts

Out: a rotting corpse.

Salvation serendipity,

I’ll find it where I can

And now I buy my boards

Unmilled and chafe

The rougher side.

The beauty of my knucklebones

Gristle gray, some oozing red.

Morning scabs do not withstand

My trips to Home Depot.

LikeLike

Hi

I just started esol course in England. Originally I come from Poland. I love Shakespeare’s sonnets expecially 135. I know Polish version and I tried to find some easy English. That how I found this site. Your article is very interesting and I realised I want more :-)

LikeLike

Thanks a ton!!! I’m majoring in English and sonnets were new to me. Was searching for clear differentiation between Petrarchan sonnet, Shakespearean sonnet & Spenserian sonnet. Finally!!! A great post and the scansion was taught clearly. Thanks for sharing this! 😉

LikeLike

You’re welcome! This remains among the most read of my posts. :-)

LikeLike

sir you just cleared all the doubts!I’m from India and loved reading your explanations and stuff,thanks!

LikeLike

You’re welcome. :-)

LikeLike

Thanks for the post; my group in AP Lit has to present about Petrarchan sonnets, and I think my teacher will be impressed by some of the insights provided here!

LikeLike

You’re welcome, Anon. Hope all goes well.

LikeLike

What is the difference between and among shakespearean,spenserian and petrarchan sonnets ?

LikeLike

Did you read this article?

LikeLike

this was super helpful.

im from ucsd btw

LikeLike

Cool. Used to visit San Diego in the winters. Beautiful climate that time of year.

LikeLike

“Their different treatment of the word might reflect a difference in their own dialects but I’m more inclined to think that Shakespeare took a more flexible approach to meter and pronunciation – less concerned than Spenser with metrical propriety. Shakespeare, in all things, was a pragmatist, Spenser, an idealist – at least in his poetry.” —– IF you think so, then you ought to read his pastoral poetry.

LikeLike

Thanks Mikerino, you could be right. I’m definitely with you in thinking that Spencer was probably more concerned with metrical propriety—and more of a poet’s poet than Shakespeare.

LikeLike

Hey Patrick–note that it’s not “Spencer” but “Spenser”!

LikeLike

Yeah, I don’t know how I get that misspelling stuck in my head, but I do—along with some others.

LikeLike

Dillon – Grace International School, Chiang Mai, Thailand

LikeLike

Wow! Hello from Vermont, USA. :) It’s a small world.

LikeLike

This is extremely helpful for all who are studying with English literature

LikeLike

Thanks Bijoy. This post is among the most widely read on the blog.

LikeLike

Hello,

I’m just preparing myself for an exam from British literature and your article came really helpful. Thank you very much.

Charles University in Prague

LikeLike

Love Prague. Know it well. Glad the post was helpful. :)

LikeLike

Hey, Patrick! Delighted to see what great legs this piece is proving to have. It richly deserves all the attention and appreciation it is receiving! Thanks, yet again, for the good words for Plutonic Sonnets, too.

Best,

Rob

LikeLike

I’m an English student at Indiana University! Researching for a paper on Renaissance sonnets. Thanks!

LikeLike

I used to visit Indiana University while at Cincinnati University. Indiana’s campus was beautiful. Cincinnati’s was a dump. Left Cincinnati but almost went to Indiana.

LikeLike

Indiana is my alma mater. Though I majored in anthropology, I took several English courses in the excellent English department, and there received my introduction to sonnets. Good luck!

LikeLike

This is amazing for my essay on Miltons sonnets.

I come from Humboldt Univewrsity, Berlin. Thank you!

LikeLike

Hey, Berlin! My home city. How I miss Berlin. Was just hanging out there in the spring. :)

LikeLike

Thank you so much! This has helped greatly for preparing for my exams. I am from Baltimore!

LikeLike

Thanks for dropping by, Tilly. Have never been to Baltimore, but close. :)

LikeLike

I’m sharing this site as a resource for my students. I am an English teacher in an American international school overseas – originally from Florida, but now working in Russia! I specifically am sharing this for the annotation samples. Thanks for sharing your work!

LikeLike

Sorry I didn’t respond sooner. For some reason WP didn’t notify me of your comment. Anyway, Russia! I’m always amazed by how far and wide these posts are read. :)

LikeLike

Pingback: My Father Hears the Aliens | Abyss & Apex

Thanks for this post! Really helpful with my upcoming exam about English literature. I’m from The Netherlands :)

LikeLike

You’re very welcome. :) Love the Netherlands.

LikeLike

Thanks for your writing, -Ib student

LikeLike

Thank you for your helpful introduction to meter. It’s cleared up a number of things.

Shakespeare’s Sonnet 129 is one of my favourites too except that I’ve never understood the very first phrase ‘an expense of spirit’. I looked up an annotated Sonnets a couple of years ago and it talked about ‘a brilliant sexual pun’. Well I think I know what that refers to but then what is the literal sense? Is it talking about wasting one’s energies, do you think?

Simon, Australia

LikeLike

Hi Simon, if one looks up ‘spirit’ in the Shakespeare Lexicon, the first definition essentially equates the spirit with the soul—the vital life force. But since Shakespeare needed a two syllable word at this point (probably), he wrote spirit instead of soul. Setting aside the sexual pun, he’s equating his soul to a ledger “A book in which a summary of accounts is laid up or preserved…” or a modern savings account. So, in that sense, he’s spending the value of his assets (his soul) on sexual excess (a waste of shame), rather than investing his assets in God. Glad you enjoyed the post. :)

LikeLike

Patrick, thanks for this latest post. I read Sonnet 129 for the first time ever and it caught me in a rare humor. In less than five minutes I had written this 14 line “sonnet.” Do you see any way this poem can be salvaged? If not, please erase it. I know I hold the record for the most execrable poem ever posted on your website, and perhaps I have exceeded that here.

The Liquid Policeman

Oh lust you bastard

Who would make a bastard

Of me alone or my descendants

On pain of visible death, or murder,

Or a dozen other horrid horrors—

Then call yourself “relief”

Of these you reinforce by

Armies until, relief upon relief,

All are lust to death enacting

Reruns of your absolution

At the shore or in the car

Orgy’s point of view intruding

Grave deferred an hour

Squirting: Ye shall overcome!

LikeLike

Yeah, I’m not seeing a way to salvage it. Definitely falls under the doggerel end of the spectrum, I’m afraid. But there’s no accounting for taste. :)

LikeLike