High Fantasy & the Oratorical Style:

The Use of Style in the Creation of the Secondary World

As early as the sixteenth century, Cervantes had killed the romance with Don Quixote, a novel which was both the culmination and the greatest parody of the romance form, and which introduced a new style of prose narrative in what Northrop Frye calls the “low mimetic” mode. Low mimetic writing deals with the life of ordinary people, with the everyday life we live, seen from the inside, where the mythic and high mimetic modes treat the life of heroes and kings, seen from the outside.(i)

As early as the sixteenth century, Cervantes had killed the romance with Don Quixote, a novel which was both the culmination and the greatest parody of the romance form, and which introduced a new style of prose narrative in what Northrop Frye calls the “low mimetic” mode. Low mimetic writing deals with the life of ordinary people, with the everyday life we live, seen from the inside, where the mythic and high mimetic modes treat the life of heroes and kings, seen from the outside.(i)

Style is not often discussed in its relation to the creation of a secondary world, or as Tolkien expressed it, in its contribution to the creation of literary(ii). Yet the style in which narrative is written is the most tangible portion of any work and to disregard it is to disregard its most fundamental feature.

At the time when Cervantes wrote his narrative in prose it was an age of verse with strictly observed metrical patterns. The choice was provocative and unmistakable. He himself said of the work: “It is so conspicuous and void of difficulty that children may handle him, youths may read him, men may understand him, and the old may celebrate him.” It was as much a part of the work as the characters within it. The twentieth century is the age of prose. There are no major works in verse. The closest a juvenile novel comes to verse may be discovered in Make Lemonade by Virginia Euwer Wolff. It is written, as it were, in broken prose — the purpose being, perhaps, to imitate the cadence of the characters’ speech. There is, however, nothing to separate it from prose but line breaks.

But for such obvious diversions, the real stylistic difference between the high mimetic mode and the low mimetic mode (iii) is now far more difficult to pinpoint occurring within the confines of prose. The “high mimetic modes [treating] the life of heroes and kings, seen from the outside” would seem to have, arguably in the twentieth century, a home in the genre of fantasy. Yet how does the high mimetic mode, as found in the cantos of Spenser or the lofty blank verse of Milton, translate into prose — the century’s predominant mode? The answer may be found in Rhetoric. Rhetoric was first classified by the Greeks as a means of codifying the techniques by which an orator might sway his audience. Rhetoric therefore has its origins in oratory. It is only natural then that one should find those same devices used in the epic poetry of Homer, Spencer, or Milton. The poet is addressing the audience, as it were, as an orator. He is relating events and wishes to communicate them effectively and persuasively. It is only natural then that the writer of High Fantasy, in his attempt to more persuasively relate the events of his world, would consciously or subconsciously utilize the rhetorical devices of the orator. The oratorical voice, that is, will lend weight to the narrative. This is a High Style which, for the sake of clarity, I’ll call the Oratorical Style.

The genre examined will be a narrow one — that wherein a secondary world is created. Susan Cooper’s The Dark is Rising cannot be contrasted with J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit (1) or Lord of the Rings because she does not attempt to create a secondary world. The more effective contrast is between The Wizard of Earthsea and Robin McKinley’s The Hero and the Crown or Lloyd Alexander’s The Book of Three.

The Figures of Oratorical style in Le Guin and Tolkien

Ursula K. Le Guin and J.R.R. Tolkien, it is broadly agreed, have both most successfully created secondary worlds — A Wizard of Earthsea and The Lord of the Rings. Among the features the books hold in common is an achieved high mimetic style within the confines of prose. This high style, the oratorical style, is achieved by the use of rhetorical figures historically common to the poetry of tragedy and the epic poem, themselves rooted in oratory. The following contains the first, and perhaps the most important of the six figures to be examined.

A feeling of fear had been growing in [Fatty Bolger] all day, and he was unable to rest or go to bed: there was a brooding threat in the breathless night air. As he stared out into the gloom, a black shadow moved under the trees; the gate seemed to open of its own accord and close again without a sound. iv

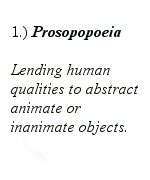

The figure prosopopoeia v, personification, is found in the poetry of Homer, medieval sagas and epics, and naturally enough in Milton; though which, in the serious poetry of the twentieth century has all but died out vi. It is telling that it is alive and well in the literature of high fantasy, which “[treats] the life of heroes and kings.”

The figure prosopopoeia v, personification, is found in the poetry of Homer, medieval sagas and epics, and naturally enough in Milton; though which, in the serious poetry of the twentieth century has all but died out vi. It is telling that it is alive and well in the literature of high fantasy, which “[treats] the life of heroes and kings.”

In the example above, the night is breathless and the night air is brooding. Tolkien is, perhaps, unique in the way in which he uses prosopopoeia to effectively create an elemental force that both threatens and sustains the characters within it. The landscape contains the same elemental force as the good and evil that struggles to control it. Adding to the impression of the animate within the inanimate, the gate seems “to open of its own accord and close again”. The world itself becomes, as here, a character within its own universe.

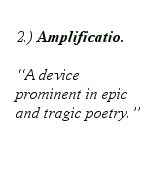

A second figure, perhaps less common today, found in epic poetry is amplificatio vii. The Longman Dictionary of Poetic Terms provides the following definition:

A second figure, perhaps less common today, found in epic poetry is amplificatio vii. The Longman Dictionary of Poetic Terms provides the following definition:

The elaboration or, sometimes, the contraction of a statement (as in Meios). Cicero considered this device of enlargement and ornament “one of the highest distinctions of eloquence.” Quintilian listed four types of a.: 1.) by augmentation (incrementum), 2) by comparison, 3) by reasoning, and 4) by accumulation (congeries). The device is prominent in epic and tragic poetry.

The figure of amplification is one often confused by rhetoricians. It is, for example, treated by some as its own figure and by others it is treated as a category of figures. The term amplification shall be used for the category and amplificatio as the figure. The figure may be seen in the following:

When he joined Ged and Serret for supper he sat silent, looking up at his young wife sometimes with a hard, covetous glance. Then Ged pitied her. She was like a white deer caged, like a white bird wing-clipped, like a silver ring on an old man’s finger…viii

Syntactic parallelism is used — a series of similes — to elaborate upon the nature of Serret. It may also be observed more fully in the following paragraph:

As their eyes met, a bird sang aloud in the branches of the tree. In that moment Ged understood the singing of the bird, and the language of the waterfalling in the basin of the fountain, and the shape of the clouds, and the beginning and end of the wind that stirred the leaves…ix

Examples like these are far less frequent, as shall be shown, in the writings of Robin McKinley and Lloyd Alexander, revealing a concerted effort by Le Guin to recreate in the realm of prose the techniques previously reserved for the poetry of the epic tradition. This figure may also be found in Tolkien. The following example of amplificatio is achieved by the parallelism of anologia (analogy) which in A Handbook to Sixteenth Century Rhetoric, is described by Quintillion as a figure “used for amplification, [that] seeks to rise from the less to the greater…”

The hobbits ran about for a while on the grass, as he told them. Then they lay basking in the sun [1] with the delight of those that have been wafted suddenly from the bitter winter to a friendly clime, or [2]of people that, after being long ill and bedridden, wake one day to find that they are unexpectedly well…x

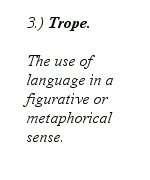

The third figure which will be considered in the creation of the oratorical style is called the Trope. Again referring to The Longman Dictionary of Poetic Terms the following definition is offered:

The third figure which will be considered in the creation of the oratorical style is called the Trope. Again referring to The Longman Dictionary of Poetic Terms the following definition is offered:

A general term for FIGURATIVE LANGUAGE, that is, language whose semantic meaning must be taken in a metaphorical or figurative sense rather than its literal sense. Poetic devices such as METAPHOR, METONYMY, SIMILE, and SYNECDOCHE fall under the categories of tropes.

We will concern ourselves only with Metaphor, and at that, only with Verbal Metaphor (2), as it is considered the most potent form of metaphor. The paragraph following provides two examples:

Once more she lifted her strange bright eyes to him, and her gaze pierced him so that he trembled as if with cold. Yet there was fear in her face, as if she sought his help but was too proud to ask it. xi

When Le Guin writes that “once more she lifted her strange bright eyes to him”, the use of the verb lifted is an example of Trope — figurative language. It is a figure which, among other effects, can add a tremendous degree of weight and formality, can elevate the prose idiom by introducing a primarily poetic affect. The formality introduced further reinforces the presence of the fictive narrator, the orator, mentioned earlier. Compare this with a comparable passage from Robin McKinley’s The Hero and the Crown.

She looked up at him and smiled: a lover’s smile, sweet and brilliant, but it was directed at him; her eyes looked at something invisible that she herself did not recognize, and yet his heart stirred in a way he did not recognize. xii

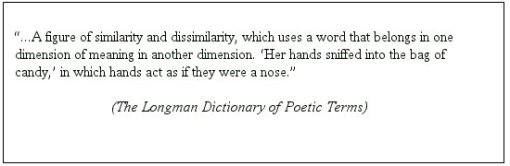

We perceive the character’s actions directly. It may be said of it that it is less poetic and therefore more immediate. It is stylistically compatible with the low mimetic mode which “deals with the life of ordinary people, with the everyday life we live, seen from the inside.” We do as the character does and the division between narrator and character is blurred. The reader’s initial impression is not of an oratorical delivery. It may be argued that “her eyes looked at something” is an example of prosopopoeia, however it is not. Prosopopoeia relies upon catachresis (3), of which this is not an example. Le Guin’s “Her gaze pierced him” is an example of catachresis as is McKinley’s “his heart stirred,” although McKinley’s verbal metaphor is so overused as to be more readily considered a dead metaphor.

Another figure, antisagoge, especially with the conjunctive FOR, is ubiquitous especially in the prose of fable and fairy tale but is also found in fantasy. It is rarely found, significantly, outside of these genres. It is often over-used by clumsy writers because of its feeling that it elevates prose. The Longman Dictionary offers the following definition:

Another figure, antisagoge, especially with the conjunctive FOR, is ubiquitous especially in the prose of fable and fairy tale but is also found in fantasy. It is rarely found, significantly, outside of these genres. It is often over-used by clumsy writers because of its feeling that it elevates prose. The Longman Dictionary offers the following definition:

A logical figure dealing with cause and effect, or antecedent and consequence. In a., the antecedent and consequence are linked together in a logical dimension: “Do as your father commands / and you will inherit his lands…” A. Is often used in discursive as well as poetic PROSE.

The following is an example which follows immediately on the paragraph already quoted from page 119 and so some of that paragraph will be included.

He saw… how they had used his fear to lead him, and how they would, once they had him, have kept him. They had saved him from the shadow, indeed, for they did not want him to be possessed by the shadow until he had become a slave of the Stone.

The bolded portion is the consequence and the italicized portion is the antecedent. In this construction the antecedent and the consequence are reversed. The figure may also be found in Tolkien, though with less frequency than with Le Guin.

Many eyes turned to Elrond in fear and wonder as he told of the Elven-smiths of Eregion and their friendship of Moria, and their eagerness for knowledge, by which Sauron ensnared them. For in that time [Sauron] was not yet evil to behold… xiii

The next figure, one of the most common of the six figures considered here, found especially in the prose of high fantasy, and especially in the writing Le Guin, is Acervatio or, as it is more commonly known in Greek, polysyndeton. The Longman Dictionary of Poetic Terms again provides the definition defining it as “a grammatical device of rhythm and balance in rhetoric that employs the repetition of conjunctions to effect measured thought and solemnity…” (Bold by Author) It should be noted that Quintillion includes adverbs and pronouns as characteristic connecting particles. xiv It is a rhetorical device which, if we are to use Milton’s Paradise Lost as a model of the high mimetic mode, finds its home most clearly in this mode. The following example will suffice as the figure is so frequent as to need no further examples.

The next figure, one of the most common of the six figures considered here, found especially in the prose of high fantasy, and especially in the writing Le Guin, is Acervatio or, as it is more commonly known in Greek, polysyndeton. The Longman Dictionary of Poetic Terms again provides the definition defining it as “a grammatical device of rhythm and balance in rhetoric that employs the repetition of conjunctions to effect measured thought and solemnity…” (Bold by Author) It should be noted that Quintillion includes adverbs and pronouns as characteristic connecting particles. xiv It is a rhetorical device which, if we are to use Milton’s Paradise Lost as a model of the high mimetic mode, finds its home most clearly in this mode. The following example will suffice as the figure is so frequent as to need no further examples.

Now what Pechvarry and his wife and the witch saw was this: the young wizard stopped midway in his spell, and held the child a while motionless. Then he had laid little Ioeth gently down on the pallet, and had risen, and stood silent, staff in hand. xv

I have only bolded those conjunctions which are grammatically unnecessary, serving rather stylistic concerns. The figure of polysyndeton, that is, describes the use of conjunctions which unnecessarily connect words or phrases in a series. As an extension to this is Le Guin’s polysyndetic use of and and but between phrases and sentences. The following paragraph illustrates Le Guin’s extensive use of the technique, — an uncommon feature, significantly, in the low mimetic style; and which illustrates the writer’s conscious effort to recreate oratory. The polysyndetic conjunctions have been bolded.

To Petchvarry it seemed that the wizard also was dead. His wife wept, but he was utterly bewildered. But the witch had some hearsay knowledge concerning magery and the ways a true wizard may go, and she saw to it that Ged, cold and lifeless as he lay, was not treated as a dead man but as one sick or tranced. xvi

The final figure, hyperbaton, is such a frequent figure in the realm of fable, fairy tale, and high fantasy as to need little explanation. It is a “generic name for rhetorical figures that work through a reorganization of normal word order.” A specific type of hyperbaton, for example, is anastrophe (involving only two words), a “grammatical construction in which an INVERSION or reversal of the normal word order takes place for the sake of emphasis in meaning, rhythm, melody or tone.” xvii Tolkien uses hyperbaton and its various types throughout The Lord of the Rings where it heightens the tone of the language. “Like a deer he sprang away. Through the trees he sped. On and on he led them, tireless and swift, now that his mind was at last made up. The woods about the lake they left behind.” xviii It is also especially frequent where the intent of the author writing fantasy is to obsolesce the language spoken by the characters.

The final figure, hyperbaton, is such a frequent figure in the realm of fable, fairy tale, and high fantasy as to need little explanation. It is a “generic name for rhetorical figures that work through a reorganization of normal word order.” A specific type of hyperbaton, for example, is anastrophe (involving only two words), a “grammatical construction in which an INVERSION or reversal of the normal word order takes place for the sake of emphasis in meaning, rhythm, melody or tone.” xvii Tolkien uses hyperbaton and its various types throughout The Lord of the Rings where it heightens the tone of the language. “Like a deer he sprang away. Through the trees he sped. On and on he led them, tireless and swift, now that his mind was at last made up. The woods about the lake they left behind.” xviii It is also especially frequent where the intent of the author writing fantasy is to obsolesce the language spoken by the characters.

The Analysis

The six rhetorical figures described above are not those most commonly found in the oratorical style of high fantasy. Other figures are equally common within this style — simile, hypotaxis (subordination) and polysyndetic connectives in the writings of Le Guin and, hyperbaton and prepositional metaphor in the writings of Tolkien are so ubiquitous as to seem less a reflection of style than of an author’s habit of thought. I have chosen the six figures above only because they were the first of the many I happened to isolate.

Nevertheless, these figures are common to all writers in whatever medium. None of these figures are exclusive and so the distinction is one of degree. The following table will compare the frequency of these figures in six books: A Wizard of Earthsea by Ursula Le Guin, The Two Towers by J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe by C.S. Lewis xix, The Taran Wanderer by Lloyd Alexander xx, The Hero and the Crown by Robin McKinley xxi, Milton’s Paradise Lost xxii, and Shizuko’s Daughter by Kyoko Mori xxiii. The final two are a control. The novel by Mori provides an example of contemporary realistic fiction. If the suppositions concerning these figures are correct, that they are figures primarily associated with the high mimetic mode, with oratory, then they should occur with the least frequency in Mori — for there is no need to persuade when one writes realistic fiction — and with the most frequency in Milton. The first fifteen pages from each book will be examined. Narrative and dialogue will be treated separately.

Lastly, it ought to be said that these numbers only point to a larger pattern. It might be argued that such a small sampling hardly argues for a consistent style. Yet if all the rhetorical figures used by the writers of High Fantasy (those writing within the oratorical style) were tallied, they would prove this sampling to be an accurate indicator of a larger stylistic consistency.

Conclusion

McKinley and Lewis use the least figures followed by Alexander. Alexander and Lewis’ fantasies are clearly written for a younger audience and so the use of oratorical figures is restrained and of the most obvious type. There is no sense of the orator. Yet neither is the orator’s voice present in McKinley’s work, which, in tone, comes closest to the contemporary realistic fiction of Mori. Depending on the experience and preference of the reader, the lack of the orator’s presence may produce a disjunctive affect and may even harm her attempt to create a secondary world. She is, in effect, using a low mimetic style in a high mimetic mode; she is speaking of times past with a twentieth century voice. As is apparent, Tolkien and Le Guin use the most figures of oratory, writers who are considered to have most successfully created a secondary world, no doubt, reinforced by the oratorical style. The oratorical voice removes the narrator into the world which he or she is describing, and so helps to create a more self contained universe.

1 The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings offer two very different narrative voices. It wasnít until the Lord of the Rings, in fact, that Tolkien attempted and succeeded in creating a high style, in the same sense that Paradise Lost is written in a high style. The narrative of the Hobbit is a much more personable style. This is achieved primarily by the rhetorical figure Aversio, the sudden alteration from the third person to the second (which never occurs in The Lord of the Rings)p. 160, and by Digressio, or more simply digressions, lending to the narrative a certain home-spun confiding quality.

2“Some verb metaphors are derived from verbs, some from adjectives, and some from compressed noun phrases. The sentence ‘I have blinded myself with optimism’ could have been derived from either the verb ‘to blind’ or the adjective ‘blind.’ We can transform the noun simile ‘He ran away as fast as a rocket can fly’ into the verb m. ‘He rocketed away…’” (The Longman Dictionary of Poetic Terms. See Metaphor.)

3“…A figure of similarity and dissimilarity, which uses a word that belongs in one dimension of meaning in another dimension. ‘Her hands sniffed into the bag of candy,’ in which hands act as if they were a nose.” (The Longman Dictionary of Poetic Terms)

i “Literary Realism and Its Effects” 6.

ii J.R.R. Tolkien, “On Fairy-Stories,” in his Tree and Leaf, Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1965, p.47.

iii Northrop Frye, Anatomy of Criticism, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1957, p. 33.

1. If superior in degree to other men and to the environment of other men, the hero is a divine being, and the story about him will be a myth in the common sense of a story about a god.

2. If superior in degree to other men and to his environment the hero is the typical hero of romance, whose actions are marvelous but who is himself identified as a human being. The hero of romance moves in a world in which the ordinary laws of nature are slightly suspended: prodigies of courage and endurance, unnatural to us, are natural to him, and enchanted weapons, talking animals, terrifying ogres and witches, and talismans of miraculous power violate no rule of probability once the postulates of romance have been established. Here we have moved from myth, properly so called, into legend, folk tale, m‰rchen, and their literary affiliates and derivatives…

3. If superior in degree to other men but not to his natural environment, the hero is a leader. He has authority, passions, and powers of expression far greater than ours, but what he does is subject both to social criticism and to the order of nature. This is the hero of the high mimetic mode, of most epic and tragedy…

4. If superior neither to other men nor to his environment, the hero is one of us: we respond to a sense of his common humanity, and demand from the poet the same canons of probability that we find in our own experience. This gives us the hero of the low mimetic mode, of most comedy and of realistic fiction…

5. If inferior in power or intelligence to ourselves, so that we have the sense of looking down on a scene of bondage, frustration, or absurdity, the hero belongs to the ironic mode. This is still true when the reader feels that he is or might be in the same situation as the situation is being judged by the norms of greater freedom.

iv J.R.R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring, New York, Ballantine Books, 1973, 238.

v Prosopopoeia,” The Longman Dictionary of Poetic Terms, 1989 ed.

“A rhetorical figure of definition that through vivid and imaginative description lends human qualities to an abstraction, or to an animate or inanimate object.”

vi “Personification,” The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics, 1993 ed.

“The following enumeration of abstractions in Gray’s [18th c.] ëOde on a Distant Prospect of Eton College shows how such personifications had lost their capacity to produce emotional effects like those in medieval morality plays or in Milton:

These shall the fury Passions tear

The vultures of the mind,

Disdainful Anger, pallid Fear,

And Shame that skulks behind;

Or pining Love shall waste their youth,

Or Jealousy with rankling tooth,

That inly gnaws the secret heart,

And Envy wan, and faded Care

Grim-visaged, comfortless Despair,

And sorrow’s piercing dart.

vii Lee A. Sonnino, A Handbook to Sixteenth Century Rhetoric, New York, Barnes & Noble, Inc., 1968 (see Amplificatio).

viii Le Guin, 114.

ix Le Guin, 35.

x J.R.R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring, New York, Ballantine Books, 1973, p. 199.

xi Ursula K. Le Guin, A Wizard of Earthsea, New York, Bantam Books, 1977, p.118.

xii Robin McKinley, The Hero and the Crown, New York, Greenwillow Books, 1984, p. 145.

xiii Ibid. 318.

xiv The Handbook of Sixteenth Century Rhetoric, 19.

xv Le Guin, 81.

xvi Le Guin, 81-82.

xvii The Longman Dictionary of Poetic Terms.

xviii Tolkien, The Two Towers, 26.

xix C.S. Lewis, The Lion, the Witch, and The Wardrobe, New York, Houghton Mifflin, 1968.

xx Lloyd Alexander, The Taran Wanderer, New York, Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1967.

xxi Robin McKinley, The Hero and The Crown, New York, Greenwillow Books, 1984.

xxii John Milton, Paradise Lost, ed. Roy Flannagan, New York, MacMillan Publishing Company, 1993.

xxiii Kyoko Mori, Shizukoís Daughter, New York, Henry Holt and Company, 1993.